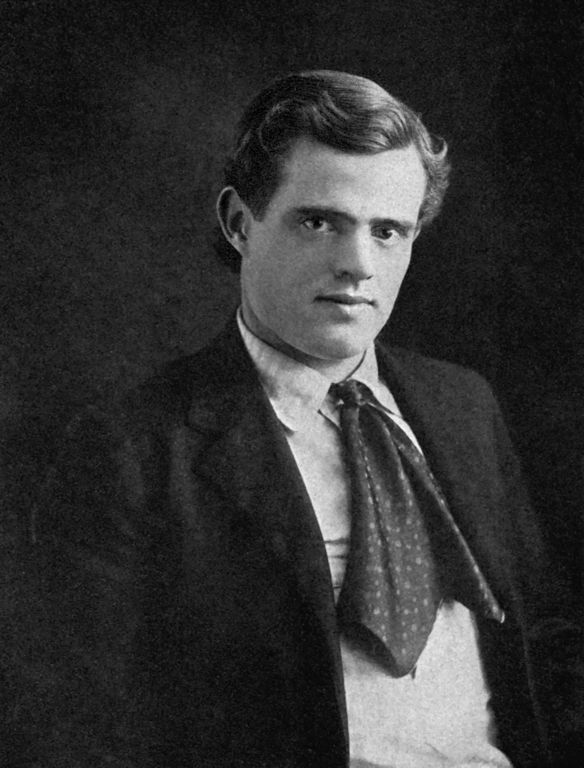

46 Jack London (1876 – 1916)

Amy Berke; Robert Bleil; and Jordan Cofer

From https://archive.org/details/littlepilgrimage00harkuoft (Little Pilgrimages page 235)

Wikimedia Commons

Public Domain

“Let us be very humble,” Jack London once wrote to no less a reader than American President Teddy Roosevelt. “We who are so very human are very animal.” Committed to producing 1000 words a day, London authored before his death at the age of forty over 400 works of non-fiction, twenty novels, and almost 200 short stories in numerous genres ranging from journalistic social criticism to juvenile, adventure, dystopian, and science fiction. As a teenager in Oakland, California, London was a voracious reader but received only a sporadic and mostly informal education. Throughout his youth he supported his family by working in mills and canneries, upon sailing boats, and even as an oyster pirate. Before he was twenty-two, he had spent time in jail for vagrancy, lectured publicly on socialism, attended one semester at the University of California, and ventured to the Canadian Yukon in search of gold. The prolific and adventurous London soon found great success as a writer, authoring many books while sailing around the world in his private yacht, and eventually becoming America’s first millionaire author. From the time of his youth, London was swept up in the intellectual and political movements of his day. He was especially influenced by the writings of Friedrich Nietzsche, Charles Darwin, and Karl Marx. The theme that unites these three great thinkers and that appealed to London is struggle: Marx saw history as a struggle between classes; Darwin saw nature as a struggle for survival between species; and Nietzsche saw society as a struggle between brilliant individuals and social institutions. London’s jobs and adventures at the bottom of the work force, in the arctic, and at sea combined with the ideas of these thinkers to become the subjects of his popular literature.

A literary naturalist, London is arguably best known today for his stories about dogs, most notably the novels Call of the Wild (1903) and White Fang (1906), and the story included here, “To Build a Fire” (1908). “To Build a Fire” is an excellent example of literary naturalism, for its plot centers around a man’s struggle for survival. Interestingly, London published an earlier draft of this same story in 1902 in the juvenile Youth’s Magazine, in which he gave his protagonist a name (Tom Vincent) and set him out alone in the Yukon without a dog. However, in the revised and much more famous version of the story you read here, London does not name the man but instead has given him a dog. As man and dog journey together on a frozen trail, London shows how heredity and environment are just as much a part of the human condition as culture and individual character.

Friedrich Nietzsche a nineteenth century German philosopher whose rejection of traditional religious views and his writings on nihilism influenced a number of artists and intellectuals of the time.

Charles Darwin was a British naturalist and author best known for his contributions to evolutionary theory in his description of the process of natural selection. His important work, Origin of the Species (1859), influenced a number of artists and intellectuals of the time.

Karl Marx, who was born in Prussia and later lived in London, was a nineteenth century philosopher whose political and economic theories (collectively known as Marxism) formed the basis of the modern practice of Communism. Marx’s views on class struggle and power were highly influential during the nineteenth century and beyond.