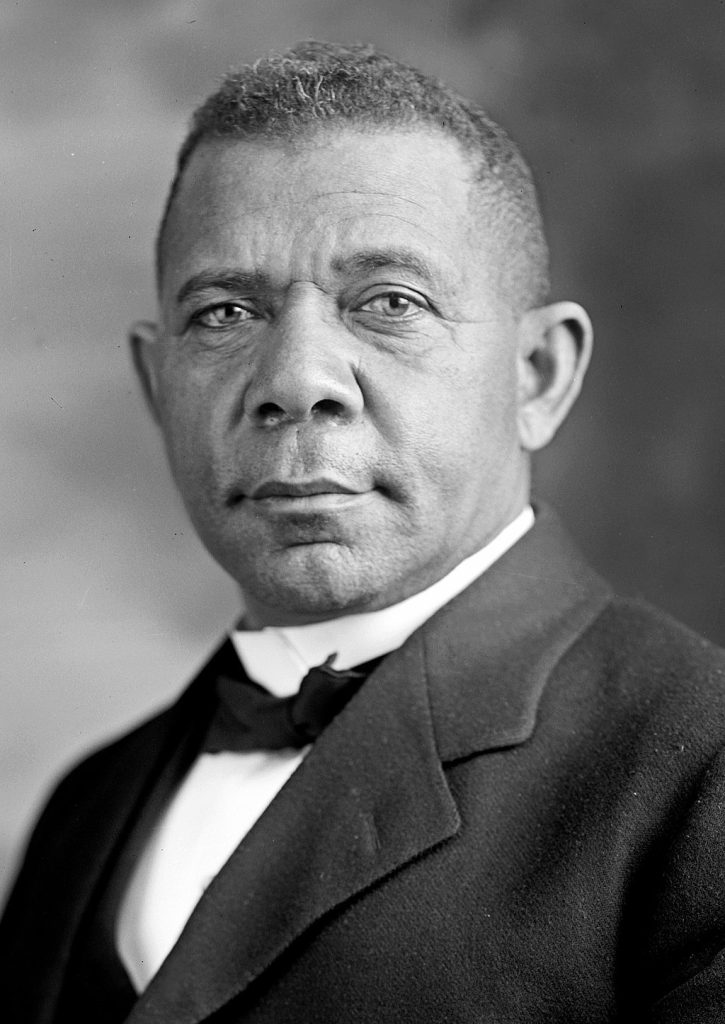

48 Booker T. Washington (1856 – 1915)

Amy Berke; Robert Bleil; and Jordan Cofer

Wikimedia Commons

Public Domain

Born a slave in Virginia, Booker T. Washington grew up to become the most influential black author and activist of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. As discussed in his autobiography, Up from Slavery (1901), Washington spent his early childhood working as a slave on a plantation. After Emancipation, and while still a boy, he first worked with his stepfather in the coalmines and salt foundries of West Virginia and then as a houseboy. At the age of fourteen, Washington left home to attend the Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute in Virginia, a segregated school for minorities, where he worked as a janitor while learning to be an educator. Washington distinguished himself at the Hampton Institute, ultimately returning after graduation at the invitation of the school’s principal to teach there. In 1881, at the age of twenty-five, Washington was hired to build and lead the Tuskeegee Normal and Industrial Institute (now Tuskeegee University), a new school in Alabama whose mission was to train African Americans for agricultural and industrial labor. The school was so poorly funded that Washington and his students famously had to make their own bricks and construct their own school buildings. Through Washington’s inspiring leadership and tireless fundraising, Tuskeegee grew and prospered. In 1895, Washington gave a five-minute speech at the Atlanta Cotton State and International Exposition that propelled him to the forefront of American politics and culture. American presidents called on him for advice about race relations and white business leaders sought him out to coordinate charitable giving to black institutions, earning Washington the moniker “the Moses of his race” in newspapers of the era.

Washington wrote almost twenty books in his lifetime, including several autobiographies, a biography of Frederick Douglass, and inspirational self-improvement texts such as Sowing and Reaping (1900) and Character Building (1902). Two chapters from Washington’s biography, Up From Slavery, are included here. In the first chapter, Washington recounts his childhood up until the time of Emancipation. In the fourteenth chapter, he reprints his Exposition Address and discusses its startlingly positive reception by a largely white audience that up to that point was fearful of America’s black population. Unlike contemporaries such as W. E. B. Du Bois, Washington did not criticize the Supreme Court’s 1896 ruling in Plessy v. Ferguson that the nation’s different races should be treated as “separate but equal.” Instead, he sought to work within the law’s segregationist restrictions. Washington pragmatically wrote his biography to showcase the industry and integrity of all African Americans rather than to demonize his former owners or celebrate his personal accomplishments. As you read Washington’s two chapters, consider how Washington uses the form of the slave narrative to give examples not only of the horrors of slavery but also of harmonious and honorable race relations.

The process by which an individual or community is set free from slavery or some other form of legal confinement.

A school for the education of African-Americans living in the former confederacy founded by Booker T. Washington at

Tuskegee, Alabama in 1881. The school exists today as Tuskegee University.

A legal and economic system in which certain individuals are treated as an legally considered the property of others. This form of slavery is also called chattel slavery.