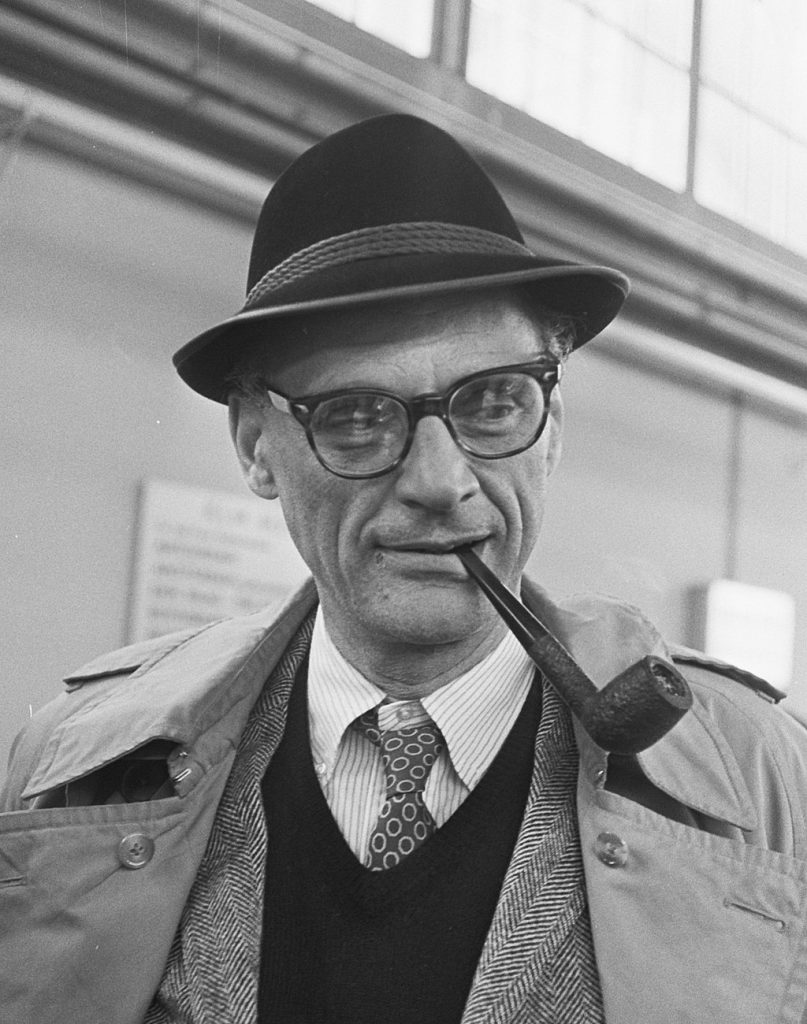

74 Arthur Miller (1915 – 2005)

Amy Berke; Robert Bleil; Jordan Cofer; and Doug Davis

Photographer Eric Koch

Wikimedia Commons

CC BY-SA 3.0

Known best for his ironic commentaries on the American dream, Arthur Miller’s plays capture the disillusionment, the emptiness, and the ambivalence of individual Americans in the twentieth century. His most famous plays, Death of a Salesman (1949) and The Crucible (1953), are staples in American literature courses from high school through university, and his precise excoriation of the American experience of freedom continues to captivate audiences.

Miller believed that playgoers responded to drama because they experienced examples of acting throughout their daily lives. In his remarks upon receiving the 2001 National Endowment for the Humanities Jefferson Medal, Miller observed:

The fact is that acting is inevitable as soon as we walk out our front doors into society. . . and in fact we are ruled more by the arts of performance, by acting in other words, than anybody wants to think about for very long.

But in our time television has created a quantitative change in all this; one of the oddest things about millions of lives now is that ordinary individuals, as never before in human history, are so surrounded by acting. Twenty-four hours a day everything seen on the tube is either acted or conducted by actors in the shape of news anchor men and women, including their hairdos. It may be that the most impressionable form of experience now, for many if not most people, consists of their emotional transactions with actors which happen far more of the time than with real people.3

In this way, Miller may be said to democratize theatre. Building on the work of the Scandinavian playwrights of the nineteenth century, Miller, along with his contemporaries Eugene O’Neill and Tennessee Williams, wrote plays that featured ordinary persons who were tortured to the point of madness by ordinary life. In doing so, Miller, O’Neill, and Williams captured the confusion, despair, and hopelessness of modern life and assured themselves a place in the American national conversation.

In Death of a Salesman, Miller presents a tragedy for the common man. Willy Loman, a marginally successful traveling salesman of women’s undergarments, is, as many students learned in high school, a low man, the most common of a type of road warrior who today fills the nation’s airports instead of its highways. Frustrated by the unbearable sameness of his travels, Willy lives within his own fantasies, and those fantasies ultimately include Willy’s dreams for his sons, Biff and Happy, while excluding Willy’s devoted wife, Linda. Willy Loman is Everyman for the twentieth century, a character whose work produces nothing and generates little in the way of material comfort. Living from paycheck to paycheck, Willy merely survives. When, ultimately, he can be neither a role model to his family nor their provider, he chooses to die rather than face exile into a state of irrelevance. Death of a Salesman is a Greek tragedy for the twentieth century in which a man who does not know who he is chooses death when he realizes his mistakes.

Death of a Salesman—Acts I & 2

Or click this link for this selection: https://joycej.kenstonlocal.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/109/2015/01/Death-of-a-Salesman.pdf