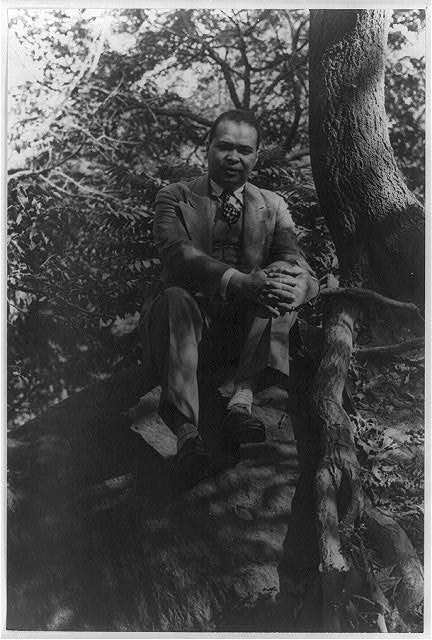

82 Countee Cullen (1903 – 1946)

Amy Berke; Robert Bleil; Jordan Cofer; and Doug Davis

Photographer Carl Van Vechten

Wikimedia Commons

Public Domain

Countee Cullen, one of the most successful writers of the early Harlem Renaissance, was himself a poetic creation. Born sometime around the turn of the twentieth century and raised until his middle teens by a woman who may have been his paternal grandmother, Cullen’s academic skills gained him early recognition and entry into New York University, where he graduated with Phi Beta Kappa honors in 1925. Nurtured in the university environment, Cullen published poetry through-

out his time at NYU and during his graduate studies at Harvard. While other members of the Harlem Renaissance, like Alain Locke, author of The New Negro (1925), advocated for artistic production that embraced distinctly African themes and styles, Cullen was a traditionalist who believed that African-American writers were entitled to the forms of English literature. In the forward to his 1927 collection Caroling Dusk, Cullen made his case succinctly: “Negro poets, dependent as they are on the English language, may have more to gain from the rich background of English and American poetry than from any nebulous atavistic yearnings toward an African influence.”6 While Cullen’s contemporaries like Langston Hughes argued for a more clearly and uniquely defined African-American literature, Cullen focused on traditional forms in his poetry and drew inspiration from the works of John Keats and A. E. Houseman.

Our two selections from Cullen’s poetry, “Yet Do I Marvel” and “Heritage,” demonstrate both Cullen’s command of the historical traditions of English and American poetry and a deep sense of irony regarding his own role as an African-American poet. Both poems were published in 1925 and showcase Cullen’s technical skill and his ambivalence. “Yet Do I Marvel,” an Italian sonnet in iambic pentameter, uses Cullen’s technical skills to remind his audience of the audacity of being a young, well-educated, African-American poet in the early twentieth century. Throughout the poem Cullen creates a sense of irony through the skill with which he interweaves classical references with nods to both John Milton and Percy Bysshe and Mary Shelley only to close with a sense of curiosity that this black poet has been made to sing in classical tones.

“Heritage,” also from 1925, uses a longer form to ask essential questions about the relationship between African-American poets and African cultural heritage. From the earliest lines of the poem, Cullen expresses distance from the African heritage embraced by other authors of the Harlem Renaissance. Building on the question, “What is Africa to me?” (10), the poem becomes a meditation on the divided self of the young African-American poet. In “Heritage,” Cullen reflects on the tensions inherent in the Harlem Renaissance: that the very education that allows a poet like Cullen to achieve widespread notoriety also exposes cultural barriers among the members of the Harlem Renaissance.