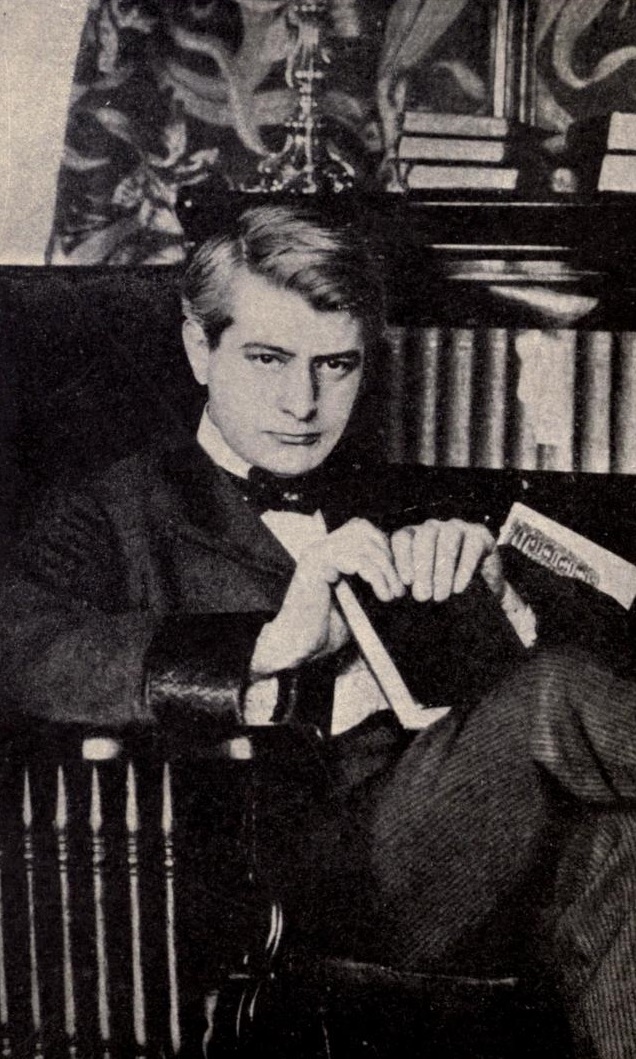

42 Frank Norris (1870 – 1902)

Amy Berke; Robert Bleil; and Jordan Cofer

From Wikimedia Commons

Public Domain

Norris grew up in an affluent household in Chicago before moving to San Francisco at the age of fourteen. His father’s jewelry and real estate businesses provided for his education in the fine arts while his mother’s interest in romantic literature introduced him to authors such as Sir Walter Scott, whose novel of medieval chivalry, Ivanhoe, heavily influenced the young Norris. At the age of seventeen, Norris left his family for Paris to study painting, revel in the city’s delights, and pen romantic tales of medieval knights that he mailed to his younger brother. Returning home, Norris attended the University of California at Berkeley before transferring to Harvard to study creative writing. Although he never received a degree, Norris’s time at Harvard was crucial to his development as an author. While there, he followed the advice of his professors and developed a more realistic style while beginning the novels McTeague (1899), Blix (1900), and Vandover and the Brute (1914). He also came, in this period, to greatly admire the French novelist Émile Zola, whose emphasis on the power of nature and the environment over individual characters inspired the composition of McTeague in particular. Returning to San Francisco, Norris wrote over 150 articles as a journalist, traveling to remote nations such as South Africa and Cuba as a war reporter for McClure’s Magazine. He then moved to New York to work in publishing, where he is credited with discovering Theodore Dreiser’s Sister Carrie (1900) for Doubleday & McClure Company. Before his untimely death from illness at the age of thirty-two, Norris published less than half a dozen novels, most notably the first two novels in his unfinished “Epic of Wheat” trilogy, The Octopus: A Story of California (1901) and (posthumously) The Pit (1903), both of which explore the brutality of the business world.

Like fellow naturalist Jack London, Norris was more interested in the raw, violent human animal than in the polite, civilized human being. In his most memorable stories, he sought to combine the scientific sensibilities of naturalism with the melodrama of romantic fiction. Norris produced a theory of naturalism in his critical essays, seeking to distinguish it from both American realism, which he condemned as too focused on the manners of middle-class society, and historical “cut and thrust” romances, which he saw as merely escapist entertainment. In the essay included here, “A Plea for Romantic Fiction,” Norris describes the Romance genre itself as a woman entering a house, imagining the intense, instructive dramas she would uncover if she were to abandon medieval swordplay and instead visit an average middle-class American home.

Norris puts his theory of naturalism into practice in his novel McTeague, crafting a titular protagonist a “poor crude dentist of Polk Street, stupid, ignorant, vulgar” with “enormous bones and corded muscles” who is more animal than man. The novel traces the upward trajectory of McTeague, from the grim poverty of life in the mining camp to the middle class life of a practicing dentist in San Francisco. However, McTeague, for all his apparent human striving, ultimately ends up where he started: in a mining camp, poor, uneducated, alone, and in trouble. He ends up a victim of instinctive, hereditary, and environmental influences and forces beyond his knowledge or his control.