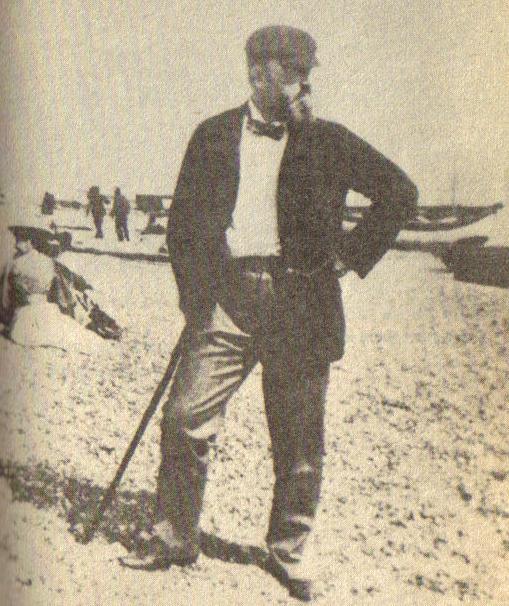

27 Henry James (1843 – 1916)

Amy Berke; Robert Bleil; and Jordan Cofer

Public Domain

Wikimedia Commons

Henry James was born in New York City in 1843 to a wealthy family. James’s father, Henry James, Sr., was a theologian and philosopher who provided James and his siblings with a life rich in travel and exposure to different cultures and languages. Having lived abroad for several years, the James family returned to America prior to the start of the Civil War, settling in Newport, Rhode Island, and later in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Unable to serve in the Union Army during the Civil War as a result of a physical disability, James attended Harvard Law School before deciding to embark on a life of traveling and writing, eventually locating to London in 1876. James’s short works soon came to the attention of William Dean Howells, then assistant editor at the Atlantic Monthly in Boston, and James and Howells eventually became proponents and literary theorists for the Realism movement in literature that had reached American shores. Although gregarious and well-connected to leading artists and intellectuals of his age, James never married, preferring to live alone and to focus his personal time on reading and writing. While James spent a number of years traveling between England and America, he lived most of his adult life in England, eventually receiving British citizenship in 1915, one year before he died.

James was one of the leading proponents of American Literary Realism, along with William Dean Howells and Mark Twain. James’s The Art of Fiction (1884) sets forth many of James’s ideas about the nature and importance of Realistic fiction. Often described as a psychological Realist, James went further than Howells and Twain in terms of experimentation with point of view, particularly in employing unreliable narrators and interior monologues. His notable novel length works, including Daisy Miller (1878), The Portrait of a Lady (1881), The Bostonians (1886), What Maisie Knew (1897), The Turn of the Screw (1898), and The Ambassadors (1903), examine a variety of themes, such as the plight of strong-willed or precocious young women or children at odds with the pressures of conventional society, tensions arising from transatlantic travel and living abroad where Americans experience clashes between American and European cultures, and emotional devastation resulting from a life not fully lived.

James’s Daisy Miller, A Study (1878) is a novella that focuses on a young independent minded American girl traveling abroad with her mother and brother in Europe who meets an American living abroad, Frederick Winterbourne. Her interactions with Winterbourne provide an examination of ways in which Daisy is viewed by those acclimated to European manners and unwritten rules of etiquette and behavior for young women. Winterbourne’s obsessive desire to understand whether or not Daisy is “innocent” provides much of the plot of the story. He cannot determine, for example, whether she is a playful young girl, simply ignorant of the cultural conventions of place and time, or whether she is more worldly and manipulative than meets the eye. Winterbourne himself becomes a psychological study: is his preoccupation with Daisy’s innocence a reflection of his own inhibitions? Is he living essentially a half-life, unable or unwilling to commit fully to another person? Is he paralyzed in a complex web of social or psychological fears? In characteristic Realist style, James offers no resolution at the end of the story, allowing questions about Daisy’s character and Winterbourne’s future to go unanswered.