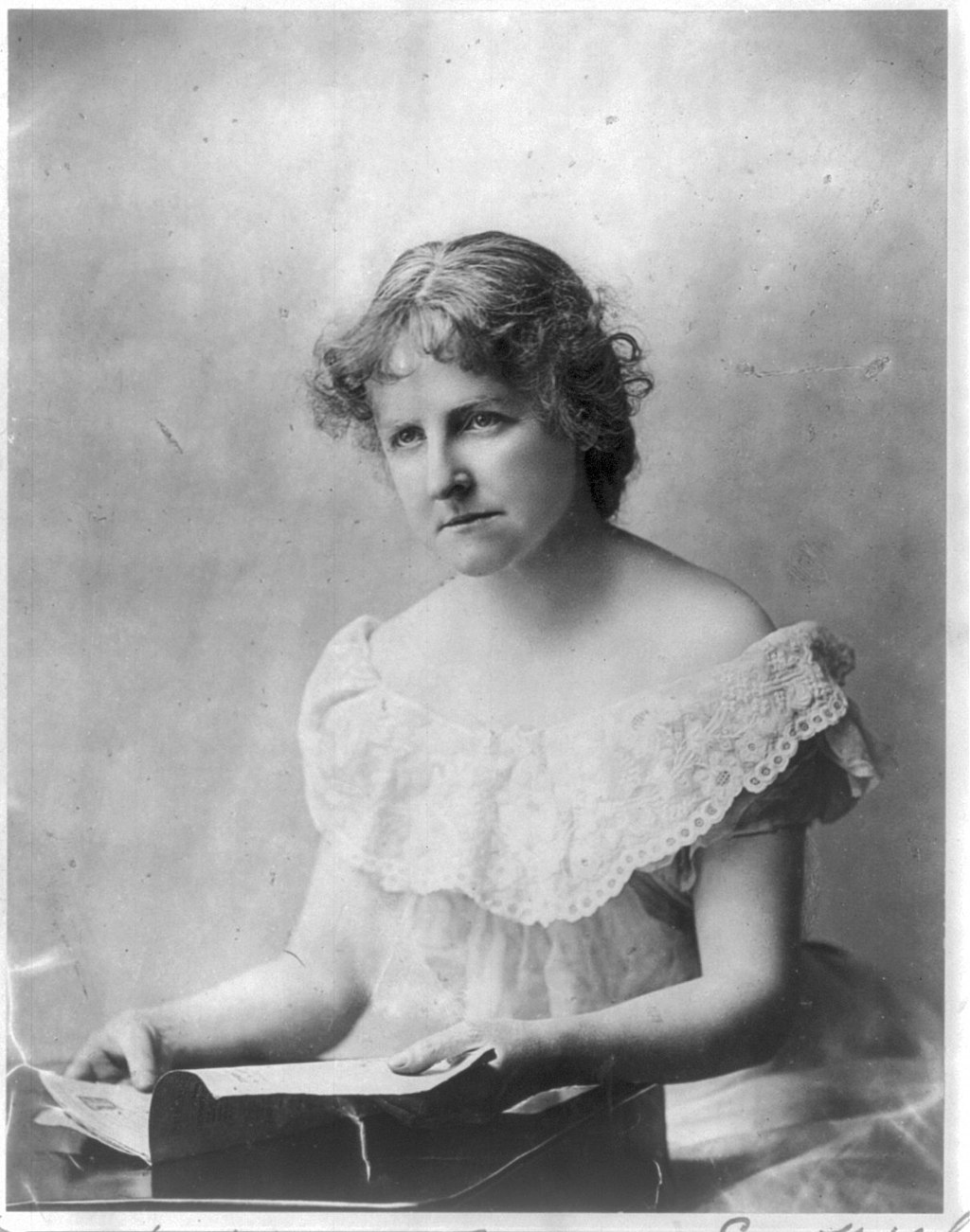

34 Mary E. Wilkins Freeman (1852 – 1930)

Amy Berke; Robert Bleil; and Jordan Cofer

Public Domain

From Wikimedia Commons

Mary E. Wilkins Freeman was born in 1852 in Randolph, Massachusetts. After high school, Freeman attended Mount Holyoke Female Seminary and later completed her studies at West Brattleboro Seminary while she pursued writing as a career. By her mid-thirties, Freeman’s parents had died, and she was alone with only a small inheritance. She lived with family friends and continued her writing, eventually supporting herself by publishing important works recognized and praised by William Dean Howells, Henry James, and other major writers of the day. While she wrote a number of novels, she is best known for her short stories, especially those that focused on the New England region. How-ever, Freeman expanded her scope and produced a variety of fictional genres, including mysteries and ghost stories. A New England Nun and Other Stories (1891) stands as her most critically acclaimed achievement, a collection of regional stories focusing primarily on women and New England life. At forty-nine, Freeman married a physician, Dr. Charles Freeman from New Jersey. However, the marriage was marred by her husband’s alcoholism, and she eventually separated from him. He was ultimately committed to the New Jersey State Hospital for the mentally ill. She died in 1930 at the age of seventy-eight after suffering a heart attack.

While Freeman was a prolific writer, she is best remembered for two important collections of short stories, A Humble Romance and Other Stories (1887) and A New England Nun and Other Stories (1891). The stories in these collections concern rural New England life and focus, in particular, on the domestic concerns of women. Like Sarah Orne Jewett, Freeman has been labeled a local colorist. However, the fiction of Jewett and Freeman generally is considered more representative of American Literary Regionalism, especially since both authors develop in their work dimensional characters whose internal conflicts are explored. Freeman’s focus in “A New England Nun” and “The Revolt of Mother” is on women’s redefining their place in the domestic sphere. In “A New England Nun,” Louisa rejects having her domestic world invaded or controlled by a male presence. She preserves dominion over her small home, gently suggesting to her betrothed Joe Daggett that they may not be a good match after all. Her choice is courageous she forgoes the role of wife and mother that her culture pressures her to accept and the peace, solitude, and self-determination that she claims in return are worth the price of her rebellion against cultural norms. In “The Revolt of Mother,” Sarah Penn is a New England woman who has accepted the traditional role of wife and mother for herself; nevertheless, like Louisa, she revolts against established cultural expectations for women. Sarah refuses to accept her husband’s dismissive attitude when she argues that the farming family needs a new house. Instead, she enacts a revolt where she, through action likened to a military general storming a fortress, makes the statement that her work on the family farm within the domestic sphere is just as important as her husband’s work as a farmer. Freeman’s fiction, as does Jewett’s, often moves beyond simply regional concerns to explore wider issues of women’s roles in late nineteenth-century America, thus approaching an early feminist realism.