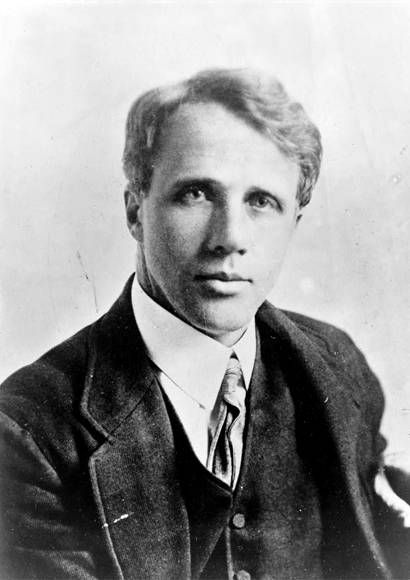

52 Robert Frost (1874 – 1963)

Amy Berke; Robert Bleil; and Jordan Cofer

When Robert Frost was asked to recite “The Gift Outright” at the inauguration of President John F. Kennedy in 1961, he was not only the first poet to be invited to participate in a presidential inauguration, he was also an American icon whose poetry was as recognizable to the nation as were Norman Rockwell’s Saturday Evening Post covers. Yet like his contemporary Rockwell, Frost’s poems reflect a rapidly changing cultural landscape in which the warm glow of memory was tinted by the cold reality of a highly mechanized, and often cruel, world. Frost was no passive megaphone for a comfortable past; like other Modernists, Frost melded traditional forms to the American vernacular to produce poetry that was strikingly American and contemporary.

Listeners and readers who are unfamiliar with Frost’s poetry often remark on the consistency of his poetic voice. Many of the poems, in fact, appear to originate from the same person, an older New England gentleman who spends much of his time reminiscing about the past, remarking wistfully on the changes taking place around him, and celebrating those rare moments when he has stepped out of the norm. Thus, poems like “The Road Not Taken,” are often recited at high school graduation ceremonies as a way to encourage students to take risks and celebrate life. Closer inspection of the poems reveals that this voice is not Frost’s at all, but that of an alter ego who exists not to highlight the past glories, but to underline very contemporary frustrations with a decaying world.

“Mending Wall,” a poem written around the time of Frost’s fortieth birthday in 1914, is a strong introduction to his use of this alter ego. A dramatic monologue in forty-five lines of iambic pentameter, the poem opens with the vague pronouncement, “Something there is that doesn’t love a wall,” and proceeds to spell out the conditions for this seasonal activity, that of mending the fence that separates two farms. As the speaker and his neighbor proceed to rebuild the wall, each one responsible for the stones that have fallen onto his own side, the first farmer pauses to reflect on how it is that every year the wall requires new attention even though no one, save for a few hunters, has been observed disturbing the stones. This annual cycle of decay and reconstruction is at the heart of this poem, and the need for annual maintenance occurs not only in the world of fences, but in the world of human relationships as well.

This idea of continual decay and maintenance in human relationships provides a useful frame for understanding “Home Burial,” a longer narrative poem that describes the apparently divergent responses of a husband and wife to the death of one of their children. A primer in the relationship between appearance and reality as the wife and husband struggle to understand their individual responses to this most recent death, the poem continues the theme of decay and rebuilding that is apparent in “Mending Wall.” As the husband and wife appear to move closer together in the poem, they must also rebuild trust in their own relationship. Throughout Frost’s poetry this cycle of decay and reconstruction continues unabated.