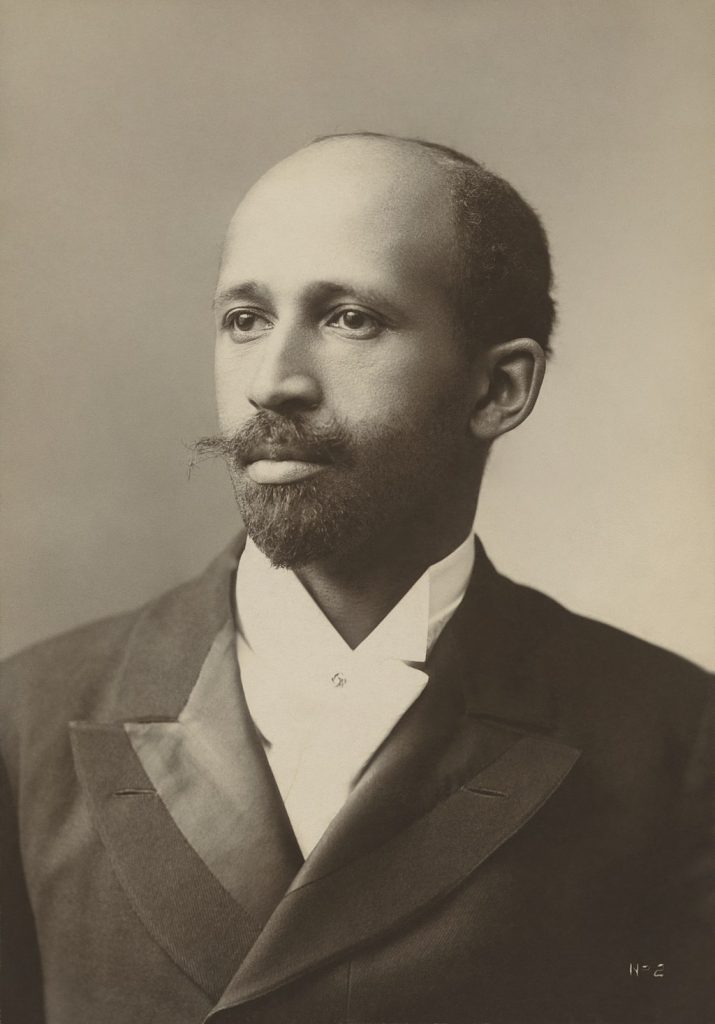

50 W.E.B. Du Bois (1868 – 1963)

Amy Berke; Robert Bleil; and Jordan Cofer

William Edward Burghardt Du Bois was born in Massachusetts to an affluent family in Great Barrington, a town with few African-American families. Du Bois describes his youth as pleasant until, while in school, he realized that his skin color, not his academic ability, set him apart from his peers. While growing up in Massachusetts, Du Bois self-identified as “mulatto” before moving to Nashville to attend Fisk University, where he first began to encounter Jim Crow laws. After finishing his bachelor’s degree at Fisk University, Du Bois began graduate study at Harvard University.

While completing his graduate work, Du Bois was awarded a prestigious one-year fellowship at the University of Berlin, where he was able to work with some of the most prominent social scientists of his day. In 1895, Du Bois completed his Ph.D., becoming the first African American to earn a Ph.D. from Harvard University. While at Harvard, Du Bois was an academic standout; indeed, Harvard University Press later published his dissertation as the first volume in their Harvard Historical Studies series.

After completing his Ph.D., Du Bois went on to hold multiple teaching appointments, first at Wilberforce College, then at the University of Pennsylvania, before moving to Atlanta University where he produced his classic work, Souls of Black Folk (1905). In 1910, Du Bois left the academy to move to New York City, where he co-founded the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and served as the editor of the NAACP’s official publication, The Crisis. Furthermore, Du Bois was a central orchestrator of the Harlem Renaissance. His essay “The Talented Tenth,” which was a chapter from his book, The Negro Problem (1903), argued that the best African-American artists (the talented “tenth” he dubbed them) were capable of producing art as complex as any white artist. In his writings, Du Bois was openly critical of Washington, whom he saw as an accommodationist (Du Bois disagreed with many of Washington’s views and was especially angered by the result of Plessy v. Ferguson). By 1920, Du Bois grew frustrated with what he viewed as a lack of positive movement on racial progress. He spent the second half of his career focusing on legislative reform for national race relations, as well turning his attention to the socio-economic conditions of African Americans in the U.S. Late in life, a disillusioned Du Bois renounced his American citizenship, joined the Communist party, and moved to Ghana (1961), where he remained until his death in 1963.

Throughout his life, Du Bois remained one of the most influential academics of his time; however, he is best known for his book, Souls of Black Folks, which is a compilation of fourteen essays. In “Of Our Spiritual Strivings,” Du Bois introduces the idea of “double consciousness,” possibly his most famous literary/academic contribution. Du Bois describes double consciousness as the “sense of always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others, of measuring one’s soul by the tape of a world that looks on in amused contempt and pity. One ever feels his two-ness an American, a Negro; two souls, two thoughts” (12).

A term from W.E.B. DuBois’ essay, ‘The Talented Tenth,’ referring to the top 10% of African-Americans as cultural and political leaders. It was used widely during the Harlem Renaissance.