34 Biopsychosocial History and Collateral Data

Alexandria Lewis

Content Outline, Competency, and KSAs

II. Assessment and Intervention Planning

IIA. Biopsychosocial History and Collateral Data

KSAs:

– The components of a biopsychosocial assessment

– The components and function of the mental status examination

– Biopsychosocial responses to illness and disability

– Biopsychosocial factors related to mental health

– The indicators of psychosocial stress

– Basic medical terminology

– The indicators of mental and emotional illness throughout the lifespan

– The types of information available from other sources (e.g., agency, employment, medical, psychological, legal, or school records)

– Methods to obtain sensitive information (e.g., substance abuse, sexual abuse)

– The indicators of addiction and substance abuse (Refer to the chapter about Addiction and Substance Use)

– The indicators of somatization

– Co-occurring disorders and conditions

– Symptoms of neurologic and organic disorders

– The indicators of sexual dysfunction

– Methods used to assess trauma (Refer to the chapter about the Impact of Trauma and Trauma-Informed Care)

– The indicators of traumatic stress and violence (Refer to the chapter about the Impact of Trauma and Trauma-Informed Care)

Overview

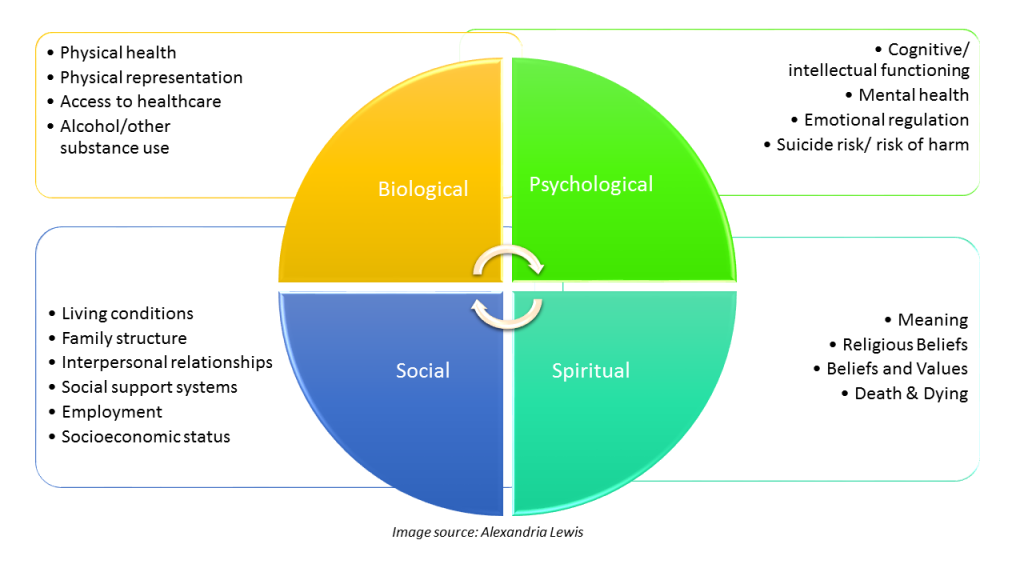

The Components of a biopsychosocial assessment

Image Accessibility Description:

Biological:

- Physical health

- Physical representation

- Access to healthcare

- Alcohol/other substance use

- Current/history medications (prescribed and over the counter)

- Family history

Psychological:

- Cognitive functioning

- Mental health

- Emotional regulation

- Suicide risk/risk of harm

- Current/history medications (psychotropic medications)

- Family history

Social:

- Living conditions

- Family structure

- Interpersonal relationships

- Social support systems

- Employment

- Socioeconomic status

- Legal history

Spiritual:

- Meaning

- Religious beliefs

- Beliefs and values

- Hope

The components and function of the mental status exam

A mental status examination (MSE) provides an assessment of a client’s cognitive, emotional, speech, judgment, and psychological functioning at a specific point in time.

Components of an MSE:

- Appearance:

- Observation of the client’s physical presentation, including dress, grooming, and any physical abnormalities.

- Behavior:

- Assessment of the client’s activity level, eye contact, facial expressions, and general demeanor.

- Speech:

- Evaluation of the client’s speech patterns, including rate, volume, articulation, and coherence.

- Mood and Affect:

- Analysis of the client’s emotional state and the appropriateness of their emotional responses.

- Thought Process:

- Examination of the client’s thought patterns, assessing for logic, coherence, and relevance.

- Thought Content:

- Identification of delusions, hallucinations, obsessions, and other abnormal thoughts.

- Perception:

- Noting any perceptual disturbances such as hallucinations or illusions.

- Cognition:

- Evaluation of cognitive functions such as orientation, memory, attention, and abstract thinking.

- Insight and Judgment:

- Assessment of the client’s awareness of their own condition and their ability to make reasonable decisions.

Exam Tips

- Watch for any answer choices that make assumptions about clients and lack a strengths-based lens.

biopsychosocial responses to illness and disability

Using a biopsychosocial approach to seeking to understand clients’ experiences requires considering how biological, psychological, social, and spiritual factors influence health and illness.

For additional context, refer to the section Effect of Disability on Biopsychosocial Functioning Throughout the Lifespan (Chapter 33: Diversity, Social, Economic Justice, and Oppression).

biophysocial factors related to mental health

The following are examples of biological, psychological, and social factors.

Biological Factors:

- Genetics (family history of mental health)

- Neurobiology (neurotransmitters and balance such as serotonin, dopamine)

- Physical health including chronic illness, brain injuries, and hormonal changes

Psychological Factors:

- Trauma history

- Stress

- Cognitive processing

- Emotional regulation

- Self-esteem

- Coping

- Personality traits

- Attachment style

- Thought patterns

Social Factors:

- Family dynamics/relationships

- Social support

- Socioeconomic status (e.g., access to healthcare, employment benefits)

- Cultural factors (e.g., language barriers, health beliefs/practices, gender roles, age, cultural norms, discrimination, religious/spiritual beliefs)

indicators of psychosocial stress

Psychosocial stress can impact not just psychological health but physical health. Psychological stress does not occur in a vacuum and can result from ongoing/continued stressors.

Examples of experiences that can lead to psychological stress:

- Family relationship dynamics (e.g., divorce, separation, intimate partner violence).

- Grief/loss

- Workplace dynamics (e.g., discrimination, harassment, negative work environment, high work demands, bullying)

- Financial problems (e.g., unemployment, debt, poverty)

- Social relationships (e.g., social isolation, conflict with friends, caregiving responsibilities)

- Life transitions (e.g., relocation, retirement, parenting, graduation, new job)

- Health (e.g., chronic illness, mental health)

- Environmental (e.g., natural disasters, community violence, access to housing)

- Legal issues (e.g., custody cases, debt, incarceration)

- Educational stressors (e.g., bullying, academic demands)

Psychosocial stress can impact individuals in various ways:

- Emotional (e.g., anxiety, depression, irritability)

- Cognition (e.g., negative thought patterns, difficulty concentrating)

- Behaviors (e.g., social isolation/withdrawal, changes in social behaviors, substance use)

- Physical (e.g., fatigue, headaches, muscle tension, sleep disturbances, blood pressure)

Self-Check

Basic medical terminology

Self-Check

Indicators of mental and emotional illness throughout the lifespan

Mental and emotional experiences can manifest differently depending on developmental stages, cultural contexts, and individual life experiences. When reading questions on the ASWB exam, if there is an age of the client in the question stem, this might indicate there is a lifespan connection to the correct answer.

Note: Click the drop down icons.

Types of information available from other sources

Examples provided in the KSA: Agency, employment, medical, psychological, legal, or school records.

Social workers should ensure the information they use from external sources about clients is relevant, current, and accurate. Be aware of potential bias in external records to ensure the information is applicable to supporting the client.

Informed consent should always be prioritized unless there are exceptions to confidentiality. Remember that clients must provide explicit, written consent before a social worker can access records or consult third parties, except in specific circumstances (e.g., imminent risk of harm, court orders). According to the NASW Code of Ethics, confidentiality must be protected unless there are compelling professional reasons (e.g., risk of harm to the client or others). Confidentiality limitations should be discussed early and revisited throughout the therapeutic relationship to set clear expectations.

Exceptions to Confidentiality:

- Court orders

- Suspected child abuse or neglect

- Imminent risk of harm to self or others

Exam Tips

Use your knowledge about the NASW Code of Ethics when encountering questions about informed consent, confidentiality, and legal compliance. Always consider the client’s right to privacy unless safety or legal mandates are issues in the question. The ASWB exam tests knowledge of federal laws (like HIPAA and FERPA) and universal ethical principles derived from the NASW Code of Ethics. State laws (e.g., mandatory reporting thresholds, specific licensing rules) are not tested. While they may influence practice in your jurisdiction, they are not relevant to the exam.

| Laws/Policies | Highlights |

| Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) | Protects the privacy of medical and psychological information. Social workers should request only the minimum necessary information to fulfill professional responsibilities. Understand exceptions to HIPAA, such as when disclosure is required by law (e.g., reporting abuse). |

| Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA) | Governs access to student educational records. Schools typically require parental consent for releasing records unless a student is over 18 or legally emancipated. |

| Duty to Warn/Duty to Protect | If accessing third-party information reveals imminent risk of harm to the client or others, disclosure may be required by law. |

Minors and Confidentiality: Minors generally have a right to confidentiality, but this right may be limited depending on the circumstances and jurisdiction.

Social workers must carefully balance the minor’s trust and therapeutic relationship with the parents’ right to know, particularly when safety or legal mandates are involved. While HIPAA does protect minors’ health information, state laws can vary on parental access. Keep in mind the ASWB exam is a national exam and not state specific.

Subpoenas vs. Court Orders: The NASW Code of Ethics emphasizes protecting client confidentiality to the extent permitted by law. should be notified of the subpoena or court order and involve them in decisions regarding disclosure. Some jurisdictions recognize social worker-client communication as privileged. Remember the exam is national and not state specific.

Always document the subpoena or court order, consultation with legal counsel, client notification, and any actions taken.

Note: Click on the dropdown arrow.

Self-Check

Methods to obtain sensitive information (e.g., substance abuse, sexual abuse)

Approaches to obtaining sensitive information includes:

- Building rapport: Establish a foundation of trust and safety by demonstrating respect, warmth, and nonjudgmental support. Use active listening to show clients they are being heard and valued.

- Warm Up Period: Avoid diving into sensitive topics immediately. Begin with general questions to help the client feel more comfortable. Gradually transition to more specific, sensitive inquiries as the client becomes more at ease.

- Open-Ended Questions: Encourage clients to share in their own words, giving them space to discuss their personal experiences.

- Reviewing Confidentiality: Explain what will and will not remain confidential to help clients feel informed.

- Transparency About Documentation: Let clients know what information will be documented and how it will be used. Explain documentation is intended to support their treatment, not to judge or penalize them.

- Trauma-Informed Practice: Be patient and flexible, allowing clients to share at their own pace.

- Cultural Humility: Approach sensitive topics with cultural humility, recognizing that cultural backgrounds and experiences may influence how clients perceive and discuss sensitive issues.

The Indicators of Somatization

Somatization Defined:

- “Somatization is the expression of psychological or emotional factors as physical (somatic) symptoms. For example, stress can cause some people to develop headaches, chest pain, back pain, nausea or fatigue. Disorders where somatization manifests range from somatic symptom disorder (previously called somatization disorder) to malingering” (Robertson, n.d.).Reference: Robertson, S. (n.d.). What is somatization? News Medical Life Sciences. https://www.news-medical.net/health/What-is-Somatization.aspx

Exam Tips

When examining exam questions, consider that it can be ‘normal’ for stress to cause temporary physical symptoms including headaches, stomach aches, muscle tensions, etc. Depending on the lens of the test writers, questions about somatization might be presented through the lens of pathology and not holistically. Western culture tends to have a bias toward separating mind and body when viewing life experiences. This could also be the lens of a question, which could seem like a trick question. When in doubt, consider how the question is written and what the ASWB is looking for with the answer (i.e., even when this differs from how you engage in social work practice).

Myths to Consider about Somatization:

- Myth #1: People who experience somatization are really not experiencing physical symptoms; these are just ‘made up.’

- Fact: Physical symptoms are real and should be validated.

- Myth #2: Somatization is rare.

- Fact: Somatization is not rare. Some people present to their primary care physician with physical symptoms that may have psychological origins. Due to the lack of connection of mind and body, these experiences can be overlooked and even disenfranchised.

- Myth #3: People who experience somatization are just seeking attention.

- Fact: Individuals with somatization are not intentionally exaggerating their symptoms.

Use Caution:

- Behavioral and medical professionals should use caution in assuming clients do not have real and serious medical conditions. Unexplained symptoms may coexist with somatic symptom and related disorders or could eventually be attributed to an undiagnosed medical issue. A comprehensive, collaborative approach involving thorough medical evaluation and mental health assessment is critical to providing ethical and effective care. This ensures that clients’ concerns are validated and their well-being prioritized, without dismissing the potential interplay between physical and psychological health. Social workers can play a significant role in supporting clients, including ways to advocate for their medical care (i.e., especially given how the medical system refers patients to multiple providers who might not collaborate with each other).

A diagnosis of somatic symptom disorder is not based solely on the absence of a medical explanation for physical symptoms. Somatic symptom disorder is characterized by distressing somatic symptoms coupled with excessive thoughts, feelings, or behaviors related to these symptoms.

Somatic Symptom Disorder Diagnostic Criteria (DSM 5 TR)

A. One or more somatic symptoms that are distressing or result in significant disruption of daily life.

B. Excessive thoughts, feelings, or behaviors related to the somatic symptoms or associated health concerns as manifested by at least one of the following:

- Disproportionate and persistent thoughts about the seriousness of one’s symptoms.

- Persistently high level of anxiety about health or symptoms.

- Excessive time and energy devoted to these symptoms or health concerns.

C. Although any one somatic symptom may not be continuously present, the state of being symptomatic is persistent (typically more than 6 months).

Specify if:

- With predominant pain (previously pain disorder): This specifier is for individuals whose somatic symptoms predominantly involve pain.

Specify if:

- Persistent: A persistent course is characterized by severe symptoms, marked impairment, and long duration (more than 6 months).

Reference: American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Somatic symptom and related disorders. In Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed., text rev.).

YouTube Video Resource: Somatic Symptom Disorder- Causes, Symptoms, Diagnosis, Treatment, and Pathology by Osmosis from Elsevier (direct link)

Self-Check

Co-Occurring disorders and conditions

Co-occurring conditions (also might be referred to as dual diagnosis) are defined as: “mental disorders or other health conditions that a person has at the same time. These may interact with each other, affecting a person’s symptoms and health outcomes” (National Institute on Drug Abuse, n.d.). Co-occurring disorders are not isolated to only mental illness and substance use (i.e., it is likely any questions on the exam will connect to substance use since this is commonly recognized as a co-occurring disorder with a mental health diagnosis).

SAMHSA Video Resource: Screening and Treatment for Co-Occurring Mental Health and Substance Use Disorders (2 minutes)

“Co-occurring disorders are strongly associated with socioeconomic and health factors that can challenge recovery, such as unemployment, homelessness, incarceration/criminal justice system involvement, and suicide (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHA], p. 11, 2020).

Resource: SAMHSA (2020). Substance use disorder treatment for people with co-occurring disorders. https://store.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/pep20-02-01-004.pdf

Coordinate, co-located, and fully integrated are three models for providing care for individuals with co-occurring disorders (SAMHA, n.d.).

Integrated treatment has better recovery outcomes, such as quality of life, fewer hospitalizations, fewer interactions with medications, housing stability, relief from psychiatric symptoms, and improvements with substance use (SAMHA, n.d.).

SAMHSA (2020) Practice Principles of Integrated Treatment for Co-Occurring Disorders:

- Substance use disorders and mental illness are treated concurrently.

- Integrated care providers should be trained in treatment of mental illness and substance use disorders.

- Various treatment modalities and approaches used: Motivational interviewing techniques, individual therapy, group work, family therapy, and peer support.

- A multidisciplinary team approach is utilized for medication management.

Source: https://store.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/pep20-02-01-004.pdf

Exam Tip

When approaching questions on the exam, keep in mind the KSA is under the Biopsychosocial History competency. When presented with a client who has a co-occurring disorder, prioritize an option that includes assessing both diagnoses. Keep in mind how co-occurring conditions can influence each other. For instance, substance use might worsen symptoms of anxiety, and addressing both simultaneously is critical.

Symptoms of neurologic and organic disorders

As a side note, some sources refer to organic brain syndrome as an outdated term because it was used as a broad term for any cognitive or behavioral ‘dysfunction’ link to changes in the brain. This term does not differentiate between specific diagnoses (e.g., dementia vs. delirium). Also, organic brain syndrome is no longer used in the DSM (i.e., the DSM focuses on specific diagnostic categories like neurocognitive disorders).

For the purpose of the exam, the following are some distinctions between neurological and organic disorders.

Note: Click on the drop down icon.

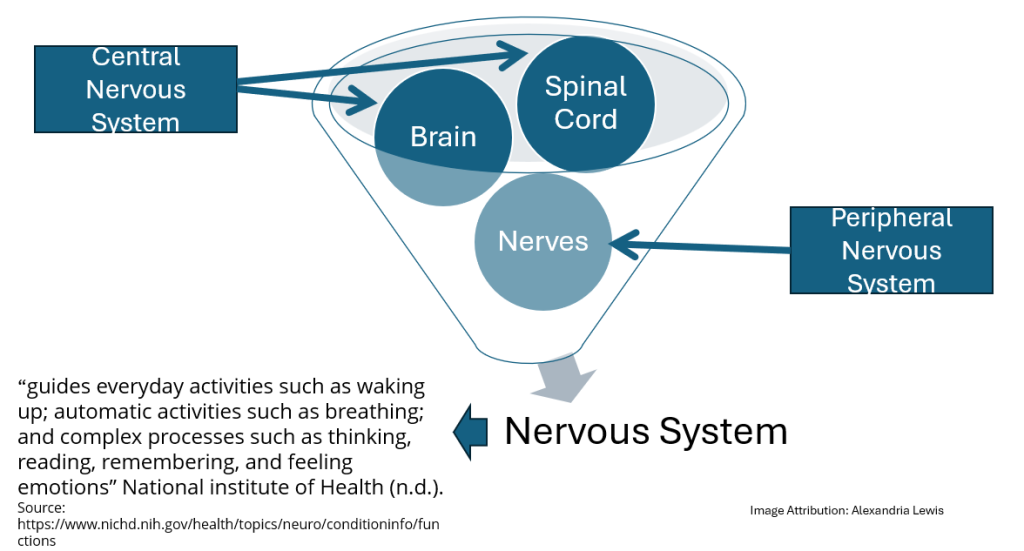

neurologic disorders

Accessible Image Description: The nervous system can be divided into the central nervous system (CNS) and the peripheral nervous system (PNS). The brain and spinal cord comprise the CNS and the nerves comprise the PNS. The nervous system can be described as guiding “everyday activities such as waking up; automatic activities such as breathing; and complex processes such as thinking, reading, remembering, and feeling emotions” (National Institute of Health, n.d.).

When studying neurologic conditions for the exam focus on how these conditions can impact a client’s physical, emotional, and cognitive functioning through the lens of assessment.

Neurologic conditions can affect the brain, spinal cord, or nerves, leading to issues such as memory loss, mood changes, or physical symptoms (e.g., tremors, weakness). These conditions may have organic causes, such as trauma, genetic predispositions, infections, or aging-related changes.

Common symptoms of nervous system disorders:

- Tremors

- Seizures

- Pain that spreads to other parts of the body (e.g., toes, feet).

- Muscle rigidity

- Weakness

- Slurred speech

- Involuntary movements (e.g., tics)

- Loss of sight or double vision

- Persistent headache

- Speech and language difficulties

- Breathing problems

- Hearing loss

- Loss of balance

- Vertigo

- Sleep problems

- Cognitive impairment

Source: Neurological Disorders

Examples of neurological disorders:

- Alzheimer’s disease

- Parkinson’s disease

- Multiple sclerosis

- ALS (amyotrophic lateral sclerosis)

- Muscular dystrophy

- Stroke

- Traumatic brain injury

- Spina bifida

- Migraines

- Carpal tunnel syndrome

- Huntington’s disease

Source: Neurological Disorders

Common Neurologic Conditions:

- Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI): Cognitive impairment, personality changes, difficulty with memory or attention, and emotional instability.

- Dementia (e.g., Alzheimer’s Disease): Gradual memory loss, disorientation, impaired problem-solving, and changes in behavior.

- Delirium: Acute confusion, disorganized thinking, and fluctuating consciousness, often caused by infections or substance withdrawal.

- Stroke (Cerebrovascular Accident): Symptoms include paralysis, difficulty speaking, and emotional changes depending on the brain area affected.

- Parkinson’s Disease: Tremors, slowed movement, muscle rigidity, and potential cognitive changes.

Assessment Highlights:

- Biological: Motor skills, sensory function, or cognition.

- Psychological: Emotional well-being, anxiety, depression, changes in personality, etc.

- Social: Relationships, occupational functioning, etc.

- Collateral Data: Include family or caregiver observations in the assessment process to gather comprehensive collateral data when a client has experienced cognitive/mental decline.

Neurologic conditions can mirror psychiatric disorders (e.g., depression vs. dementia). When new or unexplained symptoms arise, rule out organic causes before diagnosing a mental health condition. Clients with neurologic conditions benefit from multidisciplinary care, involving medical doctors, neurologists, psychiatrists, and physical or occupational therapists. Social workers play a key role in care coordination, connecting clients to resources, and providing psychosocial spiritual supports.

Organic Brain Disorders

Organic brain disorders (or organic brain syndrome, an older term) are a subset of conditions in which brain dysfunction causes significant cognitive, emotional, or behavioral impairments. These changes are due to physical or structural damage or disease within the brain. Examples: Dementia, delirium, or conditions caused by infections, substance use, etc., if there is cognitive impairment.

Self-Check

Exam Tips

- Prioritize Medical Referrals for Sudden or Unexplained Symptoms: When assessing clients with confusion, memory loss, or cognitive changes, always consider neurologic or organic causes first. Refer clients to medical providers to rule out neurologic/brain disorders.

- Differentiate by Onset and Course: Remember that dementia develops gradually and progressively, while delirium appears suddenly and often fluctuates. Identifying the timeline of symptoms is key to determining the appropriate next steps.

INdicators of Sexual Dysfunction

Defined: “Any sexual disorder characterized by problems in one or more phases of the sexual-response cycle. The particular dysfunction may be primary, in which failure in sexual functioning has always been present in the person and happens in all sexual situations; or secondary, denoting any disturbance in sexual functioning that is not lifelong or that occurs only with some partners or in some situations. Examples of sexual dysfunction include sexual desire disorders; sexual arousal disorders such as erectile dysfunction; orgasmic disorders (e.g., female orgasmic disorder, male orgasmic disorder, premature ejaculation); and sexual pain disorders (e.g., dyspareunia). Formerly called psychosexual dysfunction” (APA Dictionary of Psychology).

Biological, psychological, or social factors can impact sexual dysfunction. When assessing for sexual dysfunction, social workers should take a sensitive, comprehensive, and nonjudgmental approach.

Common Indicators of Sexual Dysfunction:

- Desire Disorders: Reduced or absent interest in sexual activity (e.g., hypoactive sexual desire disorder).

- Arousal Disorders: Difficulty becoming or staying aroused during sexual activity.

- Orgasm Disorders: Delayed, infrequent, or absent orgasms, or difficulty controlling orgasm (e.g., premature ejaculation).

- Pain Disorders: Physical discomfort during intercourse, such as dyspareunia (pain during sexual intercourse) or vaginismus (involuntary contraction of muscles making penetration painful or impossible).

Biopsychosocial Factors Contributing to Sexual Dysfunction:

- Biological:

- Chronic medical conditions (e.g., diabetes, hormonal imbalances), medication side effects (e.g., antidepressants, antihypertensives), or substance use.

- Psychological:

- Depression, anxiety, trauma, stress, or body image concerns.

- Social/Relational Factors:

- Relationship conflicts, lack of communication, or cultural/religious beliefs that affect sexual expression.

Source: American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Sexual Dysfunctions. In Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed., text rev.).

Assessment Lens:

- Building Rapport: Approach the topic with sensitivity, ensuring the client feels safe and supported.

- Open-Ended Questions: Use nonjudgmental, open-ended questions to encourage discussion.

- Review Medical History: Explore any underlying medical conditions, medications, or substance use that may contribute to symptoms.

- Screen for Psychological Factors: Assess for anxiety, depression, or trauma that may impact sexual functioning.

- Consider Cultural Context: Understand how cultural or religious norms may influence the client’s experience or willingness to discuss sexual issues.

Exam Tip

Collaborate With Medical Providers: If sexual dysfunction is suspected, referral to a medical professional (e.g., primary care physician, urologist, gynecologist) is often necessary to rule out biological causes.