29 Format Informs Information

Introduction

Throughout history, the format in which we store information has shaped what gets saved, what gets forgotten, and how we access knowledge. Whether recorded on parchment or preserved in the “cloud,” the format of information affects how we read, cite, and discover ideas.

In libraries today, you’ll encounter a wide range of formats: physical books and journals, digital eBooks, microfilm, PDF articles, and more. These formats reflect how technology has evolved and how our ways of preserving and accessing knowledge have changed. It is easy to assume digital = best, but many factors influence whether the sources we need are available in the format of our preference. A print book, for example, may be easier for one researcher to annotate, while another appreciates the ability to increase the font size on their eBook. Another book may only exist in print; there are many sources out there that have not been digitized. Perhaps a microfilm reel is the only surviving copy of the old newspaper you need. A digital article may be easily discoverable via a library databases, or maybe you need to request it as a PDF scan from another library.

Each format shapes what is visible and what might be overlooked.

Containers of Knowledge

Most people’s first thought of libraries is as physical spaces where information is organized in “containers”: books on shelves and journals bound into numbered volumes. Before the advent of digital databases, researchers could find articles in a print journal and then find related articles by flipping through the same issue or exploring other volumes on the shelf. Book readers could achieve the same goal. These physical containers helped give information a place and structure, making it clear to researchers where their information was coming from.

Free-Floating Articles in a Digital World

Today, online articles are often separated from their original containers. You might find a single article through Google Scholar or a library database without it always being obvious to you what journal it came from or what else was published alongside it. Digital search can speed up research, but it can also create loss of context. You might miss an editorial that introduced a journal issue’s theme, or not realize an article was part of a special collection on a specific topic.

For researchers, the takeaway is this: if you’re only using open web searches, you’re missing out on a huge portion of high-quality, credible information that lives below the surface.

The Role of Metadata

Metadata is “data about data”: the information that describes and provides information about an item.

- Descriptive metadata is information like the author, title, or publication date: information that tells you about an item and which allows a researcher to search for and retrieve it.

- Structural metadata identifies the organization of information within the item (e.g., a Table of Contents).

- Technical metadata includes information like file type or size.

Identifying metadata about a source allows you to effectively search for that item as well as cite it. You don’t need to memorize these terms – just be aware that all these types of information about individual resources exists and can be useful for research purposes.

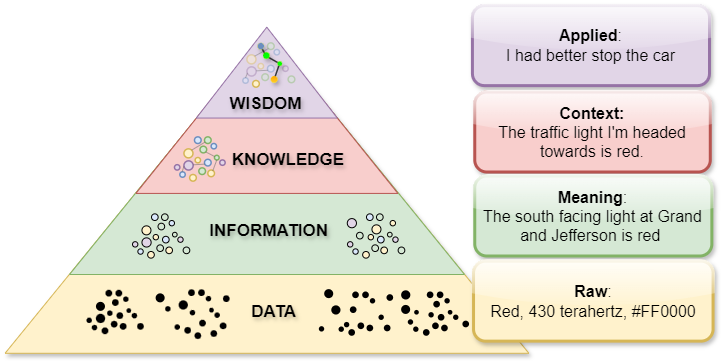

The DIKW Pyramid

The illustration below is the Data-Information-Knowledge-Wisdom (DIKW) Pyramid. It provides one framework for understanding how raw data transforms into meaningful insights. The HTML can be understood as data, unprocessed, and your browser is rendering it into information. Knowledge is what you gain when you read and learn from this material, and wisdom is what you do with that knowledge.

Data can be hard or impossible to understand on its own because it is raw and unprocessed. Information is when data is provided with more context and meaning. Knowledge is the result of information being interpreted by you. Wisdom is what results when you put that knowledge to use.

Think of research as a journey up a pyramid. At the bottom, you have tons of raw data. As you go through it and find context, it becomes useful. When you understand that information and how it connects, you gain knowledge. When you can apply that knowledge in a meaningful way, you’ve reached wisdom. Good research isn’t just about collecting or presenting a pile of data. It’s you using your critical thinking skills to climb the pyramid, and join the scholarly conversation.

The Internet and libraries, with our immense range of content, provides resources that exist as data and as information; what you do with it turns it into knowledge and wisdom.

Key Takeaways

- Format heavily influences which sources are visible (or not visible) via various search tools and strategies, including in a library search tool. Relying only on the open web means missing out on (a) potentially helpful sources and (b) important contextual information for why and how your source exists.

- Metadata offers information about a source, and it is a critical component in information organization and discovery.

- Constructing large-scale information from individual data points is a complicated process, and mirrors how the Internet converts data to a user-friendly presentation of digital knowledge.