27 Information Before the Internet

Introduction

In this chapter, we discuss (very briefly) some major developments in information technology – the formats in which words, images, sound, etc. were preserved and transmitted before the advent of the Internet. In Part One, we touch on some foundational historical milestones; in Part Two, we focus in greater detail on the technologies of the near past (specifically, the 19th and 20th centuries).

How will knowing this information make you a better researcher?

Each new development builds on the expectations and conventions of the technology that preceded it. With a basic understanding of how one advancement led to the next, you’ll be better equipped to understand research vocabulary, apply advanced search strategies, and consider the value of source formats beyond just articles and books.

Part One: A Few Important Developments

Oral Traditions

Humans have been communicating and preserving information across generations orally for thousands of years. Language and storytelling are ancient and culturally universal human traits.

Like the written word, spoken language can also be conveyed and preserved in different formats – not just regular speech, but also chanting, spoken poetry, ballads, and more. The combination of diction with rhythm, rhyme, music, or physical movements can not only create beautiful and engaging works of art, but also aid in memory.

Many modern-day traditions and stories trace their roots to information transmitted orally for generations before eventually being written down. These include religious texts (e.g., the Old Testament) and ancient epics, like the Iliad.

Oral traditions are still an important art form and cultural preservation mechanism today. Genealogy, folklore, songs, and more are still transmitted orally, but they are also recorded in the form of audio or video in various mediums.

Writing

The independent invention of writing systems in several locations/cultures (Mesoamerica, Mesopotamia, Egypt, and China) represents a dramatic change in our abilities to communicate and preserve information. A (relatively) stable, visual representation of spoken language meant that information could:

- be communicated consistently across farther distances

- include more information than a single person could reliably memorize

- be more easily preserved and standardized over long periods of time

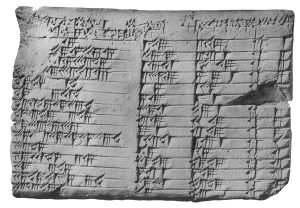

How effectively early writing samples were preserved is dependent on a variety of historical and environmental conditions, one of which is the physical medium on which they were inscribed. Today, our primary (non-virtual) medium for the written word is paper, first invented in China around the 2nd century CE.

Other materials include:

- clay tablets or pottery

- papyrus

- stone tablets or monuments

- parchment

- fabric

- wood

Writing & Libraries

With the invention and spread of various writing systems came the need for libraries, in two parts: (a) physical spaces to store and organize tablets, scrolls, etc. and (b) staff to do the collecting, organizing, and retrieval of those items.

The very first (known) library was that of Ashurbanipal, an Assyrian king in the 7th century BCE. This royal library held clay tablets on all kinds of topics, gained through both the copying work of his own scribes and military conquest. The famed Epic of Gilgamesh is the most well-known surviving work from this library.

Since then, libraries have played a crucial role in supporting research and preserving history. Historically, many libraries were funded and managed by governments, religious institutions, or wealthy private individuals. The first truly public library, funded by taxpayers rather than individual subscriptions or other sources, opened in America in the 20th century.

The Printing Press

Johannes Gutenberg (of Germany) invented the printing press in the 15th century, which again revolutionized the information landscape. Books not only became more affordable, but were more easily standardized. The result was an explosion of increasing literacy rates and the more rapid spread of new ideas across the European continent and beyond, impacting culture, education, scientific advancement, and more.

Notably, the printing press resulted in what we now call “mass communication.” Communication to enormous audiences was no longer limited to those with traditional wealth or authority, such as political or religious leaders, ushering the new “middle class” to a more prominent role in information consumption and dissemination.

Part Two: 19th and 20th Century American Libraries

Now, we take a big time jump to America. We’re focusing on this time period and cultural context to cover some important technological foundations in how libraries and research were organized. Although you may not use these technologies, the precedent they set has influenced how information is organized in the digital world, and knowing this vocabulary will help you navigate research online.

Card Catalogs

A library catalog is an organized record of all bibliographic items found in a library’s collection.

Prior to the mid-1700s, these records were kept in lists (e.g., on tablets, scrolls, paper, etc.) or handwritten/printed ledgers. As the sheer amount of items in most libraries escalated, these ledgers were replaced with slips or individual cards to represent each item.

In fact, card catalogs use multiple cards for the same item. This system allows users to browse the card collection organized in different ways: by titles, by authors, or by subjects.

Card catalogs become popular in libraries by the mid-1800s. There were multiple advantages to the card system, the main being:

- Flexibility: Using individual cards for each item made items easier to add, edit, or remove.

- Easier discovery: Library patrons could browse for books by author, title, or the subjects covered in the material.

Although many modern-day libraries have moved to digital catalogs, some others do still have functional card catalogs to support research, especially to locate older materials. Here’s a short video highlighting the current status of the card catalog at the Library of Congress, the world’s largest library (run time: 2:20):

MARC and OPACs

Henriette Avram, a computer scientist, created the MARC standard in the 1960s.

MARC (Machine Readable Cataloging) is a standardized rule set for how to format the descriptions of library items so they can be read and shared by computers.

MARC has become the international standard for formatting and sharing bibliographic data, although there are several versions of it.

When you look at a MARC record, you’ll see numerical fields that each correspond to the type of information you’re supposed to enter into that field. For example, the main author goes in field 100. In field 260, you put the publisher.

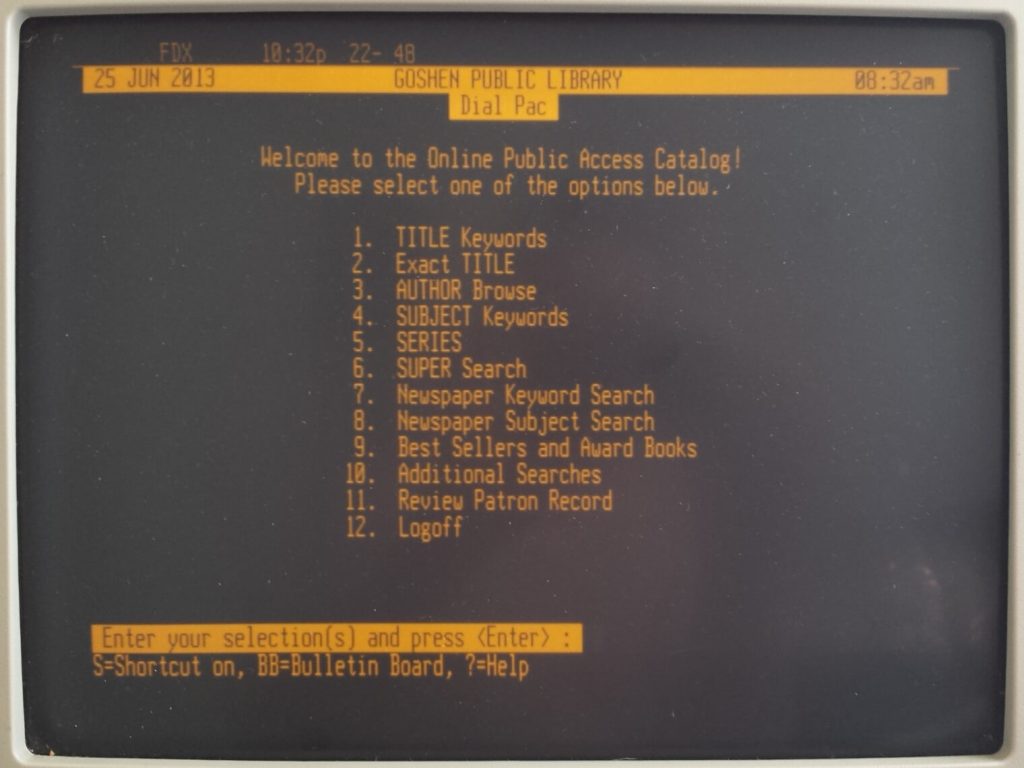

MARC allowed for the computerization of the card catalog system and the development of online public access catalogs (OPACs), which allowed patrons to search for materials on a computer rather than printed cards. Dynix is an example of a popular, early-days digital and searchable catalog.

Indexing

The continued rapid uptick in library content, especially in academic journals, increased the need for formal indexes.

An index is a list of names, subjects, and other notable content discussed in a larger work alongside the specific location those entries can be found (e.g., page numbers). Indexes which cover multiple works (e.g., many journals in a given field) often used standard vocabulary to refer to the same concepts, even if unique language is used in those journals or articles.

The purpose of many 20th-century print indexes was to help researchers locate articles on specific topics or from specific authors in their field, even if they were published in different journals or different issues of the same journal. They could go to the print index, search for their topic (or authors’ names, or another criterion), and find the specific location of relevant articles.

These indexes were the precursor to modern-day databases. Like we learned in Week 3, databases allow you to search millions of journal articles by typing in a subject, title, author, etc. without needing to search through individual journals in your field, which could cover a variety of topics in each issue.

Technology Preservation

When discussing preservation, it’s common to think of older historical materials, often paper-based. Modern technology (specifically, the Internet) is touted as the obvious way to digitize and preserve these documents.

However, there are two considerations that impact this transition:

- Digital access is not foolproof. It is less accessible for people who struggle with or can’t afford technology, it often relies on 3rd-party platforms that may decide to stop hosting that material, and it can be extremely expensive for libraries to either purchase digital materials or digitize materials themselves.

- Technology is not just a tool for preservation. As we continue to make scientific advancements, we must consider preservation of technology.

Throughout the 19th and 20th century, rapid technological developments meant that information was created and stored on a variety of non-paper and non-digital formats. Some of these mediums include floppy discs, cassettes, CDs, and VHS. Not everything can or should be converted to a digital format, and deciding the best way to store and prevent the degradation of these materials is an ongoing discussion.

Microfilm

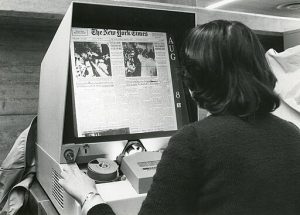

Microfilm is an excellent example of an older technology that is still a preferred and frequently-used tool for accessing historical materials even in the digital age. It preserves documents in a compact and stable format.

Microfilm comes in plastic reels of very small-scale photographs, typically of extensive and hard-to-preserve documents like old newspapers or government documents. A researcher can feed the reel through a reader, which increases the size of the image on a screen for easy viewing.

Did you know: We have a microfilm reader at UMSL? You can find it near the Public Service Desk.

Key Takeaways

- The modern-day research landscape is dependent on (a) major developments in how humans communicate, and (b) specific, pre-Internet technologies that influence today’s digital research organization.

- We cannot take the importance of writing, print, or libraries for granted, no matter how ubiquitous or inevitable they seem today. Nor can we discount the influence that oral traditions still have on preservation and the transmission of knowledge.

- Card catalogs, the MARC standard, and indexes are all examples of technology from the recent past that, even though we don’t often interact with them physically today, are important to be aware of to understand the back end of how digital research systems are organized.

- The interaction of technology and information preservation includes both how we can use technology to preserve older materials as well as how we preserve technology itself.