28 The Internet

A Very Short History of the Internet

A full history of the Internet could cover an entire class. For now, let’s cover some important developments that will help you understand why the Internet works the way it does today.

A Short Timeline of the Internet, 1957 – early 2000s

- 1957. The Soviet Union successfully launches the Sputnik satellite, catalyzing US government investment in scientific and technical projects in a “space race” with the Soviet Union. One major goal was to discover a reliable way to transmit information in the event of a nuclear attack.

- 1960s. The US Department of Defense and scientists develop ARPANET (Advanced Research Projects Agency Network), a computer network that lays the foundation for today’s Internet. The first two computers connected are at UCLA and Stanford. Later, additional research institutions, government agencies, and businesses are connected.

- ARPANET is decentralized, meaning that if one node of the network fails, the remaining computers can still communicate with each other, providing a safeguard against missile attacks or other damage.

- 1973/4. Vint Cerf and Bob Kahn develop a standardized protocol that allows different networks to communicate (TCP/IP). ARPANET later adopts TCP/IP.

- Internet Protocol (IP): provides unique but standardized addresses for every device so that messages arrive at their correct destination.

- Transmission Control Protocol (TCP): a system to guarantee that all parts of a message are delivered and in the right order.

- 1983. Debut of the Domain Name System (DNS), allowing users to type domain names (e.g., abcd.com) rather than numerical IP addresses.

- 1989. Tim Berners-Lee develops the World Wide Web (WWW) while working at CERN. The WWW relies on hyperlinks, allowing users to easily access interconnected resources. Visit the world’s first website!

- 1995: The Internet commercializes. Digital financial transactions become safer through encryption. (Two examples of businesses that start in 1995 include Echo Bay, later eBay, and Amazon.)

- 1997: The advent of Wi-Fi allows users to connect devices to the Internet via radio waves.

- 1998: Google debuts. Although other search engines have created user-friendly portals for finding and accessing web sites, Google pioneers PageRank, aka, an algorithm to better return relevant results.

- 2000s: Broadband speeds up Internet connections beyond former telephone-based lines, increasing the use of graphics, video, games, etc.

How The Internet Works

Note: This video is longer than our usual videos (nearly 20 minutes). We encourage watching the whole thing if you find this topic interesting; it’s an excellent video. However, you can get the information you need in the first 10(ish) minutes.

Organizing the Internet

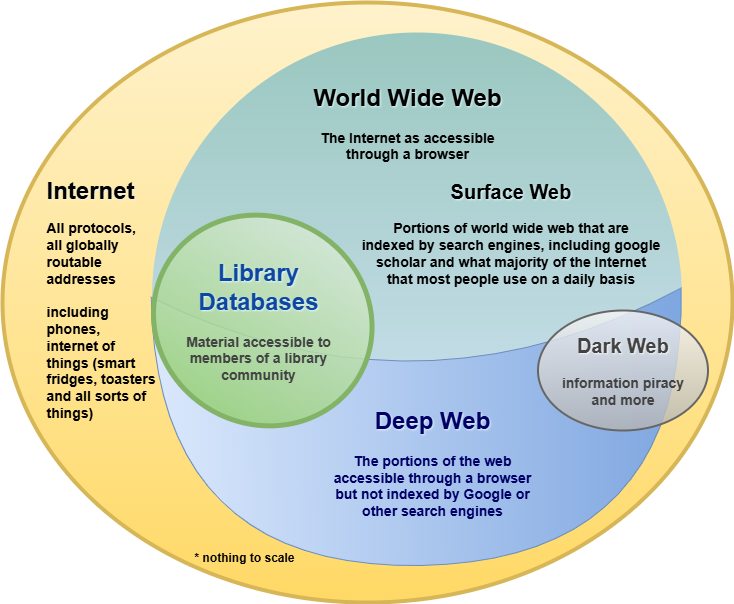

The Internet and the World Wide Web, often used interchangeably, are not actually the same thing.

The Internet is the connected computer network that provides the infrastructure for the World Wide Web (WWW), as well as email, file transfers, private databases, and other non-WWW content, to work. It allows computers to talk to each other. The WWW is all the public websites and pages you access through a browser like Chrome or Firefox.

All content on the Internet – WWW or otherwise – is hosted on servers. Servers are physical computers, typically hosted in large data centers that depend on a significant amount of power and cooling infrastructure. When you access a resource online through a browser, it determines the server “address” and requests a copy of the site, page, app, etc. to be sent to your device. The content is sent from the server to your device in small data packets, then reassembled by your browser for viewing.

The Hierarchy of the Web

The WWW is largely organized into websites, like wikipedia.com or google.com. The top-level domain (e.g., .com or .org) depends on the purpose of the site and the type of organization hosting it. The domain name (e.g., “Google” or “UMSL”) is the name of the site.

Within each website are various web pages, which act as files organized in relation to each other and the site’s home page. The specific organization of the site depends on type of content. A common structure is similar to a “tree,” where a main page branches into multiple lower-level pages.

Although what you see on a web page is typically well-formatted text, graphics, and other content, the underlying code is primarily HTML, a standardized way to tell a browser how to format and display the page content (for example, indicating that text should be in bold or italics).

You can often follow the organization of a website by looking at the URL.

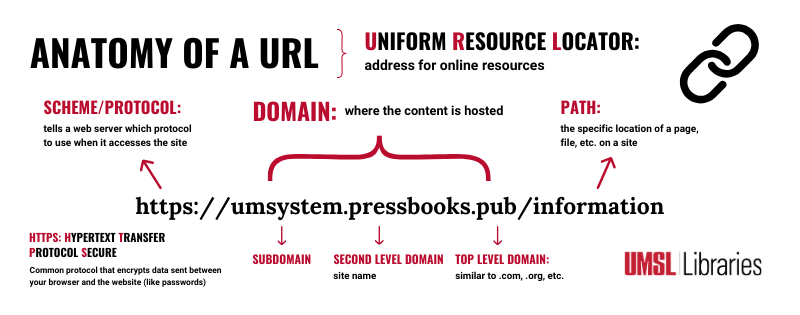

URL stands for Uniform Resource Locator. It is the string of text, punctuation, and sometimes symbols you type into a web browser to visit a website or access a file on the Internet.

For example, the content of this page is pulled from a freely-available online textbook (if you are reading it in Canvas – otherwise you’re already directly on the textbook site). The textbook is hosted on a larger site called Pressbooks, which hosts many other open educational resources. Pressbooks is both the site name and the main domain that hosts all that content. Its top-level domain is .pub, which is often used for sites that host web-based publication. The “umsystem” portion of the URL is the subdomain – in other words, the portion of the site that hosts publications from the UM System. The “/information” path refers to our specific book.

The Deep Web

Most content on the Internet is not actually publicly accessible on a web browser. The deep web refers to content that is hosted on a private server or protected by login credentials. Importantly, this material is not indexed by public search engines (like Google). Therefore, you won’t typically find these resources with a regular Google search.

The deep web includes subscription-based library databases. (Other examples include your personal email account or medical records.) Takeaway: a LOT of helpful scholarly information is NOT easily discoverable on Google. Instead, use a library search tool.

Key Takeaways

- The modern-day Internet relies on several important developments from the latter half of the 20th century, including the creation of ARPANET, standardized communication protocols, the advent of the WWW, and user-friendly ways of finding and interacting with websites (such as the domain name system and ranked search results).

- Internet content is stored on physical servers and relies on physical connections to transfer from one computer to another.

- A URL can give you clues to how a website is organized.

- Not all Internet content is publicly accessible on the WWW.