The Ethnolinguistic Perspective

Learning Objectives

After completing this module, students will be able to:

1. Define the concept of linguistic relativity

2. Differentiate linguistic relativity and linguistic determinism

3. Define the Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis (against more pop-culture takes on it) and situate it in a broader theoretical context/history

4. Provide examples of linguistic relativity through examples related to time, space, metaphors, etc.

In this part, we will look at language(s) and worldviews at the intersection of language & thoughts and language & cognition (i.e., the mental system with which we process the world around us, and with which we learn to function and make sense of it). Our main question, which we will not entirely answer but which we will examine in depth, is a chicken and egg one: does thought determine language, or does language inform thought?

We will talk about the Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis; look at examples that support the notion of linguistic relativity (pronouns, kinship terms, grammatical tenses, and what they tell us about culture and worldview); and then we will more specifically look into how metaphors are a structural component of worldview, if not cognition itself; and we will wrap up with memes. (Can we analyze memes through an ethnolinguistic, relativist lens? We will try!)

3.1 Linguistic Relativity: The Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis

In the 1920s, Benjamin Whorf was a graduate student studying with linguist Edward Sapir at Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut. Sapir, considered the father of American linguistic anthropology, was responsible for documenting and recording the languages and cultures of many Native American tribes, which were disappearing at an alarming rate. This was due primarily to the deliberate efforts of the United States government to force Native Americans to assimilate into the Euro-American culture. Sapir and his predecessors were well aware of the close relationship between culture and language because each culture is reflected in and influences its language. Anthropologists need to learn the language of the culture they are studying in order to understand the world view of its speakers. Whorf believed that the reverse is also true, that a language affects culture as well, by actually influencing how its speakers think. His hypothesis proposes that the words and the structures of a language influence how its speakers think about the world, how they behave, and ultimately the culture itself. (See our definition of culture in Part 1 of this document.) Simply stated, Whorf believed that human beings see the world the way they do because the specific languages they speak influence them to do so.

He developed this idea through both his work with Sapir and his work as a chemical engineer for the Hartford Insurance Company investigating the causes of fires. One of his cases while working for the insurance company was a fire at a business where there were a number of gasoline drums. Those that contained gasoline were surrounded by signs warning employees to be cautious around them and to avoid smoking near them. The workers were always careful around those drums. On the other hand, empty gasoline drums were stored in another area, but employees were more careless there. Someone tossed a cigarette or lighted match into one of the “empty” drums, it went up in flames, and started a fire that burned the business to the ground. Whorf theorized that the meaning of the word empty implied to the worker that “nothing” was there to be cautious about so the worker behaved accordingly. Unfortunately, an “empty” gasoline drum may still contain fumes, which are more flammable than the liquid itself.

Whorf’s studies at Yale involved working with Native American languages, including Hopi. The Hopi language is quite different from English, in many ways. For example, let’s look at how the Hopi language deals with time. Western languages (and cultures) view time as a flowing river in which we are being carried continuously away from a past, through the present, and into a future. Our verb systems reflect that concept with specific tenses for past, present, and future. We think of this concept of time as universal, that all humans see it the same way. A Hopi speaker has very different ideas and the structure of their language both reflects and shapes the way they think about time. The Hopi language has no present, past, or future tense. Instead, it divides the world into what Whorf called the manifested and unmanifest domains. The manifested domain deals with the physical universe, including the present, the immediate past and future; the verb system uses the same basic structure for all of them. The unmanifest domain involves the remote past and the future, as well as the world of desires, thought, and life forces. The set of verb forms dealing with this domain are consistent for all of these areas, and are different from the manifested ones. Also, there are no words for hours, minutes, or days of the week. Native Hopi speakers often had great difficulty adapting to life in the English speaking world when it came to being “on time” for work or other events. It is simply not how they had been conditioned to behave with respect to time in their Hopi world, which followed the phases of the moon and the movements of the sun.

In a book about the Abenaki who lived in Vermont in the mid-1800s, Trudy Ann Parker described their concept of time, which very much resembled that of the Hopi and many of the other Native American tribes. “They called one full day a sleep, and a year was called a winter. Each month was referred to as a moon and always began with a new moon. An Indian day wasn’t divided into minutes or hours. It had four time periods—sunrise, noon, sunset, and midnight. Each season was determined by the budding or leafing of plants, the spawning of fish, or the rutting time for animals. Most Indians thought the white race had been running around like scared rabbits ever since the invention of the clock.”

The lexicon, or vocabulary, of a language is an inventory of the items a culture talks about and has categorized in order to make sense of the world and deal with it effectively. For example, modern life is dictated for many by the need to travel by some kind of vehicle—cars, trucks, SUVs, trains, buses, etc. We therefore have thousands of words to talk about them, including types of vehicles, models, brands, or parts.

The most important aspects of each culture are similarly reflected in the lexicon of its language. Among the societies living in the islands of Oceania in the Pacific, fish have great economic and cultural importance. This is reflected in the rich vocabulary that describes all aspects of the fish and the environments that islanders depend on for survival. For example, in Palau there are about 1,000 fish species and Palauan fishermen knew, long before biologists existed, details about the anatomy, behavior, growth patterns, and habitat of most of them—in many cases far more than modern biologists know even today. Much of fish behavior is related to the tides and the phases of the moon. Throughout Oceania, the names given to certain days of the lunar months reflect the likelihood of successful fishing. For example, in the Caroline Islands, the name for the night before the new moon is otolol, which means “to swarm.” The name indicates that the best fishing days cluster around the new moon. In Hawai`i and Tahiti two sets of days have names containing the particle `ole or `ore; one occurs in the first quarter of the moon and the other in the third quarter. The same name is given to the prevailing wind during those phases. The words mean “nothing,” because those days were considered bad for fishing as well as planting.

Parts of Whorf’s hypothesis, known as linguistic relativity, were controversial from the beginning, and still are among some linguists. Yet Whorf’s ideas now form the basis for an entire sub-field of cultural anthropology: cognitive or psychological anthropology. A number of studies have been done that support Whorf’s ideas. Linguist George Lakoff’s work looks at the pervasive existence of metaphors in everyday speech that can be said to predispose a speaker’s world view and attitudes on a variety of human experiences. A metaphor is an expression in which one kind of thing is understood and experienced in terms of another entirely unrelated thing; the metaphors in a language can reveal aspects of the culture of its speakers. Take, for example, the concept of an argument. In logic and philosophy, an argument is a discussion involving differing points of view, or a debate. But the conceptual metaphor in American culture can be stated as ARGUMENT IS WAR. This metaphor is reflected in many expressions of the everyday language of American speakers: I won the argument. He shot down every point I made. They attacked every argument we made. Your point is right on target. I had a fight with my boyfriend last night. In other words, we use words appropriate for discussing war when we talk about arguments, which are certainly not real war. But we actually think of arguments as a verbal battle that often involve anger, and even violence, which then structures how we argue.

To illustrate that this concept of argument is not universal, Lakoff suggests imagining a culture where an argument is not something to be won or lost, with no strategies for attacking or defending, but rather as a dance where the dancers’ goal is to perform in an artful, pleasing way. No anger or violence would occur or even be relevant to speakers of this language, because the metaphor for that culture would be ARGUMENT IS DANCE.

3.1 Adapted from Perspectives, Language (Linda Light, 2017)

You can either watch the video, How Language Shapes the Way We Think, by linguist Lera Boroditsky, or read the script below.

Watch the video:

There are about 7,000 languages spoken around the world—and they all have different sounds, vocabularies, and structures. But do they shape the way we think? Cognitive scientist Lera Boroditsky shares examples of language—from an Aboriginal community in Australia that uses cardinal directions instead of left and right to the multiple words for blue in Russian—that suggest the answer is a resounding yes. “The beauty of linguistic diversity is that it reveals to us just how ingenious and how flexible the human mind is,” Boroditsky says. “Human minds have invented not one cognitive universe, but 7,000.”

Video transcript:

So, I’ll be speaking to you using language . . . because I can. This is one these magical abilities that we humans have. We can transmit really complicated thoughts to one another. So what I’m doing right now is, I’m making sounds with my mouth as I’m exhaling. I’m making tones and hisses and puffs, and those are creating air vibrations in the air. Those air vibrations are traveling to you, they’re hitting your eardrums, and then your brain takes those vibrations from your eardrums and transforms them into thoughts. I hope.

[Laughter]

I hope that’s happening. So because of this ability, we humans are able to transmit our ideas across vast reaches of space and time. We’re able to transmit knowledge across minds. I can put a bizarre new idea in your mind right now. I could say, “Imagine a jellyfish waltzing in a library while thinking about quantum mechanics.”

[Laughter]

Now, if everything has gone relatively well in your life so far, you probably haven’t had that thought before.

[Laughter]

But now I’ve just made you think it, through language.

Now of course, there isn’t just one language in the world, there are about 7,000 languages spoken around the world. And all the languages differ from one another in all kinds of ways. Some languages have different sounds, they have different vocabularies, and they also have different structures—very importantly, different structures. That begs the question: Does the language we speak shape the way we think? Now, this is an ancient question. People have been speculating about this question forever. Charlemagne, Holy Roman emperor, said, “To have a second language is to have a second soul”—strong statement that language crafts reality. But on the other hand, Shakespeare has Juliet say, “What’s in a name? A rose by any other name would smell as sweet.” Well, that suggests that maybe language doesn’t craft reality.

These arguments have gone back and forth for thousands of years. But until recently, there hasn’t been any data to help us decide either way. Recently, in my lab and other labs around the world, we’ve started doing research, and now we have actual scientific data to weigh in on this question.

So let me tell you about some of my favorite examples. I’ll start with an example from an Aboriginal community in Australia that I had a chance to work with. These are the Kuuk Thaayorre people. They live in Pormpuraaw at the very west edge of Cape York. What’s cool about Kuuk Thaayorre is, in Kuuk Thaayorre, they don’t use words like “left” and “right,” and instead, everything is in cardinal directions: north, south, east, and west. And when I say everything, I really mean everything. You would say something like, “Oh, there’s an ant on your southwest leg.” Or, “Move your cup to the north-northeast a little bit.” In fact, the way that you say “hello” in Kuuk Thaayorre is you say, “Which way are you going?” And the answer should be, “North-northeast in the far distance. How about you?”

So imagine as you’re walking around your day, every person you greet, you have to report your heading direction.

[Laughter]

But that would actually get you oriented pretty fast, right? Because you literally couldn’t get past “hello,” if you didn’t know which way you were going. In fact, people who speak languages like this stay oriented really well. They stay oriented better than we used to think humans could. We used to think that humans were worse than other creatures because of some biological excuse: “Oh, we don’t have magnets in our beaks or in our scales.” No; if your language and your culture trains you to do it, actually, you can do it. There are humans around the world who stay oriented really well.

And just to get us in agreement about how different this is from the way we do it, I want you all to close your eyes for a second and point southeast.

[Laughter]

Keep your eyes closed. Point. OK, so you can open your eyes. I see you guys pointing there, there, there, there, there . . . I don’t know which way it is myself—

[Laughter]

You have not been a lot of help.

[Laughter]

So let’s just say the accuracy in this room was not very high. This is a big difference in cognitive ability across languages, right? Where one group—very distinguished group like you guys—doesn’t know which way is which, but in another group, I could ask a five-year-old and they would know.

[Laughter]

There are also really big differences in how people think about time. So here I have pictures of my grandfather at different ages. And if I ask an English speaker to organize time, they might lay it out this way, from left to right. This has to do with writing direction. If you were a speaker of Hebrew or Arabic, you might do it going in the opposite direction, from right to left.

But how would the Kuuk Thaayorre, this Aboriginal group I just told you about, do it? They don’t use words like “left” and “right.” Let me give you hint. When we sat people facing south, they organized time from left to right. When we sat them facing north, they organized time from right to left. When we sat them facing east, time came towards the body. What’s the pattern? East to west, right? So for them, time doesn’t actually get locked on the body at all, it gets locked on the landscape. So for me, if I’m facing this way, then time goes this way, and if I’m facing this way, then time goes this way. I’m facing this way, time goes this way—very egocentric of me to have the direction of time chase me around every time I turn my body. For the Kuuk Thaayorre, time is locked on the landscape. It’s a dramatically different way of thinking about time.

Here’s another really smart human trait. Suppose I ask you how many penguins are there. Well, I bet I know how you’d solve that problem if you solved it. You went, “One, two, three, four, five, six, seven, eight.” You counted them. You named each one with a number, and the last number you said was the number of penguins. This is a little trick that you’re taught to use as kids. You learn the number list and you learn how to apply it. A little linguistic trick. Well, some languages don’t do this, because some languages don’t have exact number words. They’re languages that don’t have a word like “seven” or a word like “eight.” In fact, people who speak these languages don’t count, and they have trouble keeping track of exact quantities. So, for example, if I ask you to match this number of penguins to the same number of ducks, you would be able to do that by counting. But folks who don’t have that linguistic trait can’t do that.

Languages also differ in how they divide up the color spectrum—the visual world. Some languages have lots of words for colors, some have only a couple words, “light” and “dark.” And languages differ in where they put boundaries between colors. So, for example, in English, there’s a word for blue that covers all of the colors that you can see on the screen, but in Russian, there isn’t a single word. Instead, Russian speakers have to differentiate between light blue, goluboy, and dark blue, siniy. So Russians have this lifetime of experience of, in language, distinguishing these two colors. When we test people’s ability to perceptually discriminate these colors, what we find is that Russian speakers are faster across this linguistic boundary. They’re faster to be able to tell the difference between a light and a dark blue. And when you look at people’s brains as they’re looking at colors—say you have colors shifting slowly from light to dark blue—the brains of people who use different words for light and dark blue will give a surprised reaction as the colors shift from light to dark, as if, “Ooh, something has categorically changed,” whereas the brains of English speakers, for example, that don’t make this categorical distinction, don’t give that surprise, because nothing is categorically changing.

Languages have all kinds of structural quirks. This is one of my favorites. Lots of languages have grammatical gender; so every noun gets assigned a gender, often masculine or feminine. And these genders differ across languages. So, for example, the sun is feminine in German but masculine in Spanish, and the moon, the reverse. Could this actually have any consequence for how people think? Do German speakers think of the sun as somehow more female-like, and the moon somehow more male-like? Actually, it turns out that’s the case. So if you ask German and Spanish speakers to, say, describe a bridge, like the one here—“bridge” happens to be grammatically feminine in German, grammatically masculine in Spanish—German speakers are more likely to say bridges are “beautiful,” “elegant,” and stereotypically feminine words. Whereas Spanish speakers will be more likely to say they’re “strong” or “long,” these masculine words.

[Laughter]

Languages also differ in how they describe events, right? You take an event like this, an accident. In English, it’s fine to say, “He broke the vase.” In a language like Spanish, you might be more likely to say, “The vase broke,” or “The vase broke itself.” If it’s an accident, you wouldn’t say that someone did it. In English, quite weirdly, we can even say things like, “I broke my arm.” Now, in lots of languages, you couldn’t use that construction unless you are a lunatic and you went out looking to break your arm—[laughter] and you succeeded. If it was an accident, you would use a different construction.

Now, this has consequences. So, people who speak different languages will pay attention to different things, depending on what their language usually requires them to do. So we show the same accident to English speakers and Spanish speakers, English speakers will remember who did it, because English requires you to say, “He did it; he broke the vase.” Whereas Spanish speakers might be less likely to remember who did it if it’s an accident, but they’re more likely to remember that it was an accident. They’re more likely to remember the intention. So, two people watch the same event, witness the same crime, but end up remembering different things about that event. This has implications, of course, for eyewitness testimony. It also has implications for blame and punishment. So if you take English speakers and I just show you someone breaking a vase, and I say, “He broke the vase,” as opposed to “The vase broke,” even though you can witness it yourself, you can watch the video, you can watch the crime against the vase, you will punish someone more, you will blame someone more if I just said, “He broke it,” as opposed to, “It broke.” The language guides our reasoning about events.

Now, I’ve given you a few examples of how language can profoundly shape the way we think, and it does so in a variety of ways. So language can have big effects, like we saw with space and time, where people can lay out space and time in completely different coordinate frames from each other. Language can also have really deep effects—that’s what we saw with the case of number. Having count words in your language, having number words, opens up the whole world of mathematics. Of course, if you don’t count, you can’t do algebra, you can’t do any of the things that would be required to build a room like this or make this broadcast, right? This little trick of number words gives you a stepping stone into a whole cognitive realm.

Language can also have really early effects, what we saw in the case of color. These are really simple, basic, perceptual decisions. We make thousands of them all the time, and yet, language is getting in there and fussing even with these tiny little perceptual decisions that we make. Language can have really broad effects. So the case of grammatical gender may be a little silly, but at the same time, grammatical gender applies to all nouns. That means language can shape how you’re thinking about anything that can be named by a noun. That’s a lot of stuff.

And finally, I gave you an example of how language can shape things that have personal weight to us—ideas like blame and punishment or eyewitness memory. These are important things in our daily lives.

Now, the beauty of linguistic diversity is that it reveals to us just how ingenious and how flexible the human mind is. Human minds have invented not one cognitive universe, but 7,000—there are 7,000 languages spoken around the world. And we can create many more—languages, of course, are living things, things that we can hone and change to suit our needs. The tragic thing is that we’re losing so much of this linguistic diversity all the time. We’re losing about one language a week, and by some estimates, half of the world’s languages will be gone in the next hundred years. And the even worse news is that right now, almost everything we know about the human mind and human brain is based on studies of usually American English-speaking undergraduates at universities. That excludes almost all humans. Right? So what we know about the human mind is actually incredibly narrow and biased, and our science has to do better.

I want to leave you with this final thought. I’ve told you about how speakers of different languages think differently, but of course, that’s not about how people elsewhere think. It’s about how you think. It’s how the language that you speak shapes the way that you think. And that gives you the opportunity to ask, “Why do I think the way that I do?” “How could I think differently?” And also, “What thoughts do I wish to create?”

Thank you very much.

[Applause]

Read the following text on what lexical differences between language can tell us about those languages’ cultures.

3.2 Lexical Differences Among Languages

3.2.1 Some Reasons Languages Differ Lexically

So far we have endowed our Lexies with an amazing capacity, one that to date has only been found among human beings. Over the generations, they can now invent a very large store of labels for individuals and categories of things in the world (even categories of things not in the world). And, equally important, they can pass on this store of labels to their children.

Now let’s imagine various tribes of Lexies in different parts of the world with no contact with each other. Each tribe will experience a different environment, containing its own potentially unique set of animals and plants and its own climate and geology. Each tribe will invent words for the things in its environment that matter to it, and we will naturally expect to find words for different things in each tribe. Modern languages also differ from each other in this way. Amharic has a word for hippopotamus because hippopotamuses are found in Ethiopia, but Inuktitut does not because hippopotamuses are not found (normally) in northern Canada.

We can also expect the cultures of the different tribes of Lexies to differ. This will result in several differences in their store of words. First, certain naturally occurring things will become more important. A tribe that makes pots out of clay will want a word for clay; another tribe may not bother. Second, as culture develops, there will be more and more cultural artifacts, that is, objects produced by the members of the culture. Naturally the tribe will want words for these as well, and if they are not producing them, they will not have such words. Finally, culture results in abstractions, concepts that do not represent (physical) things in the world at all: political units, social relationships, rituals, laws, and unseen forces. These will vary a great deal in their details from tribe to tribe, and we can expect these differences to be reflected in the words that each tribe comes up with.

Culture and Nouns

Modern languages also differ from each other in these ways. Amharic has the word agelgil meaning a leather-covered basket that Ethiopians used traditionally to carry prepared food when they traveled. Other languages don’t have a word for this concept. English now has the word nerd to refer to a particular kind of person who is fascinated with technology and lacking in social skills. This is a relatively new concept, specific to certain cultures, and there is probably no word for it in most languages.

3.2.2 Differences Within and Among Languages

Exercise

Finally, we can also expect the store of words to vary among the individuals within each tribe. As culture progresses, experts emerge, people who specialize in agriculture or pottery or music or religion. Each of these groups will invent words that are not known to everyone in the tribe. Modern languages also have this property. A carpenter knows what a hasp is; I have no idea. I know what a morpheme is because I’m a linguist, but I don’t expect most English speakers to know this.

This brings up an important distinction, that between the words that a language has and the words that an individual speaker of the language knows. Because some speakers of languages such as Mandarin Chinese, English, Spanish, and Japanese have traveled all over the world and studied the physical environments as well as the cultures they have found, these languages have words for concepts such as hippopotamus and polygamy, concepts that are not part of the everyday life of speakers of these languages. Thus it is almost certainly true that Mandarin Chinese, English, Spanish, and Japanese have more words than Amharic, Tzeltal, Lingala, and Inuktitut. But this fact is of little interest to linguists and other language scientists, who, if you remember, are concerned with what individual people know about their language (and sometimes other languages) and how they use this knowledge. There is no evidence that individual speakers of English or Japanese know any more words than individual speakers of Amharic or Tzeltal.

Where New Words Come From

Furthermore, if a language is lacking a word for a particular concept, it is a simple matter for the speakers of the language to add a new word when they become familiar with the concept. One way for this to happen is through semantic extension of an existing word; we saw this earlier with mouse in English. Another way is to create a new word out of combinations of old words or pieces of old words; we will see how this works in in Chapter 5 and Chapter 8. A third, very common, way is to simply borrow the word from another language. Thus English speakers borrowed the word algebra from Arabic; Japanese speakers borrowed their word for “bread,” pan, from Portuguese; Amharic speakers borrowed their word for “automobile,” mekina, from Italian; and Lingala speakers borrowed their word for “chair,” kiti, from Swahili.

3.2.3 Lexical Domains: Personal Pronouns

What are the differences between the personal pronouns you and you guys? (There are at least two differences.)

More interesting than isolated differences in the words that are available in different languages is how the concepts within a particular domain are conveyed in different languages. We’ll consider two examples here, personal pronouns and nouns for kinship relations; we’ll look at others later on when we discuss words for relations.

A complete set of personal pronouns in my dialect of English includes the following: I, me, you, she, her, he, him, it, we, us, you guys, they, them. Note that I’m writing you guys as two words, but in most important ways it behaves like one word. For our present purposes, we can ignore the following group: me, her, him, us, them; we’re not really ready to discuss how they differ from the others. Among the ones that are left, let’s consider how they differ from each other. We have already seen how they differ with respect to person: I and we are first person; you and you guys are second person; she, he, it, and they are third person. We can view person as a dimension, a kind of scale along which concepts can vary. Each concept that varies along the dimension has a value for that dimension. The person dimension has only three possible values, first, second, and third, and each personal pronoun has one of these values.

Person is not just a conceptual dimension; it is a semantic dimension because the different values are reflected in different linguistic forms. That is, like words, semantic dimensions have both form and meaning. When we speak of “person,” we may be talking about form, for example, the difference between the word forms I and you, about meaning, for example, the difference between Speaker and Hearer, or about the association between form and meaning.

But person alone is not enough to account for all of the differences among the pronouns. It does not distinguish I from we, for example. These two words differ on another semantic dimension, number. I is singular: it refers to an individual. We is plural: it refers to more than one individual. What values are possible on the number dimension? Of course languages have words for all of the different numbers, but within the personal pronouns, there seem to be only the following possibilities: singular, dual (two individuals), trial (three individuals), and plural (unspecified multiple individuals). Of these trial is very rare, and, among our set of nine languages, dual is used only in Inuktitut. Thus Inuktitut has three first person pronouns, uvanga “I,” uvaguk “we (two people),” uvagut “we (more than two people).”

Given the two dimensions of person and number, we can divide up the English personal pronouns as shown in the table below. The third person pronouns fall into the singular group of three, she, he, and it, and the single plural pronoun they. The second person is more complicated. In relatively formal speech and writing, we use you for both singular and plural, but informally, at least in my dialect, we may also use you guys for the plural. (Note that other English dialects have other second person plural pronouns, you all/y’all, yunz, etc.) Thus we need to include both you and you guys in the plural column.

|

Singular |

Plural |

|

|

1 person |

I |

we |

|

2 person |

you |

you, you guys |

|

3 person |

she, he, it |

they |

Clearly, we need more dimensions to distinguish the words since two of the cells in our table contain more than one word. Among the third person singular pronouns, the remaining difference has to do with gender, whether the referent is being viewed as male, female, or neither. Instead of male and female, I will use the conventional linguistic terms masculine and feminine to emphasize that we are dealing with linguistic categories rather than biological categories in the world, and for the third value I will use neuter. Thus, there are three possible values on the gender dimension for English, and three seems to be all that is needed for other languages, though some languages have a dimension similar to gender that has many more values.

That leaves the distinction between you and you guys in the plural. As we have already seen, this is related to formality, another semantic dimension and a very complicated one. I will have little to say about it here, except that it is related to the larger context (not just the utterance context) and to the relationship between the Speaker and Hearer. For example, language is likely to be relatively formal in the context of a public speech or when people talk to their employers. For now, let’s assume that the formality dimension has only two values, informal and formal. The table below shows the breakdown of the English personal pronouns along the four dimensions of person, number, gender, and formality.

|

Singular |

Plural |

|

|

1 person |

I |

we |

|

2 person |

you |

formal informal you you guys |

|

3 person |

feminine masculine neuter she he it |

they |

Gaps in Pronoun Systems

Notice that there seem to be gaps in the English system. There is a word for third person singular feminine, but no word for second person singular feminine, and formality is only relevant for second person plural. Because there is no masculine or feminine you in English, we can say that you is unspecified for the gender dimension. As we will see many times in the book, languages tend to be systematic—if they make a distinction somewhere, they tend to make that distinction elsewhere—but they are not always so. English personal pronouns are systematic in one important way: the distinction between first, second, and third person is maintained in both singular and plural. But they are not in other ways, as we have just seen.

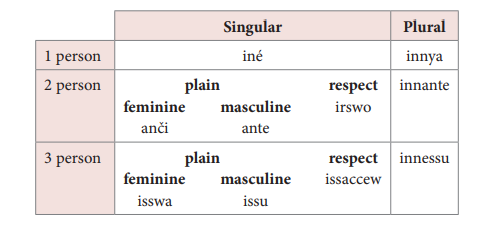

You will probably not be surprised to learn that there is nothing special about the English system; other languages organize things somewhat differently, though it seems that person and number are relevant for all languages. Here is the set of Amharic personal pronouns.

Notice that Amharic fills some of the apparent gaps that English has; for example, there is both a masculine and a feminine second person singular pronoun, while English only makes the gender distinction in third person. But Amharic is unsystematic in some ways too; while gender is relevant for singular pronouns, it is not for plural pronouns, and, as in English, it doesn’t enter into first person at all. Notice also that there is a new dimension, respect, that is relevant for Amharic pronouns, at least in second and third person singular. Respect is similar to formality, but it relates specifically to the attitude that the Speaker wants to convey toward the referent, that is, the Hearer in the case of second person and another person in the case of third person. In Amharic, there are two values for this dimension, plain and respectful. Finally, notice that while English has three values for gender, Amharic has only two, masculine and feminine. This means that one or the other of these must make do to refer to things that are neither male nor female. Many languages have only two genders, and each of these languages has its own way of determining which gender is appropriate for things that don’t have “natural” gender.

We have seen only two examples of personal pronoun systems. Other languages have quite different systems, some making use of dimensions that are not relevant for English or Amharic, some ignoring dimensions that matter for English and Amharic. For example, in many languages, including Tzeltal and Inuktitut, gender plays no role at all in the personal pronoun systems: there is no distinction like that between he and she. It is not clear why pronoun systems vary the way they do. For example, it would be wrong to assume that Tzeltal pronouns lack gender because Tzeltal speakers are less conscious of gender in the world or that children learning Tzeltal become less sensitive to gender differences than children learning English or Amharic or Spanish. At least there is no evidence for these kinds of relationships. The relationship between language and thought has been most often studied in the context of grammar, and since we are looking at personal pronouns, we are getting pretty close to grammar, but we will save this topic for later.

3.2.4 Lexical Domains: Kinship Terms

What do the meanings of the words father and uncle have in common? What sort of dimension would you need to distinguish the meanings of these words?

Now let’s look at the words we use to refer to kinship relations. We won’t consider all of the words in a given language, just some of the basic ones. Let’s start by taking two similar words and trying to figure out what dimension distinguishes their meanings, say brother and sister. This is easy since we’ve already been discussing this dimension; it’s gender.

But gender won’t help us with the distinction between daughter and mother since both are female. For these words we have to consider their relationship to the person who provides the reference point for the relationship, what cultural anthropologists (the experts on this topic) call ego. In both cases, there is a direct relationship (what anthropologists call lineal), but in one case the relationship goes in one direction (back into the past); in the other, it goes in the opposite direction (forward into the future). Let’s call this dimension “vertical separation from ego.” We can use positive and negative numbers to represent values on this dimension. In the case of mother, the separation is –1 (one generation back); in the case of daughter, it is +1 (one generation forward).

But these two dimensions won’t suffice to distinguish all basic English kinship terms. What about mother and aunt? Both are female, and both are separated by –1 from ego. What distinguishes these two relations is the closeness of the relationship to ego. For mother, the person is in a lineal relation to ego. For aunt, we need to go back another generation, to ego’s grandparents, to find a common ancestor. We will call this dimension “horizontal distance from ego” and represent it again with a number (but no sign). For mother, we will say the distance is 0; for aunt (and cousin and niece), it is 1. Here is a list of some English kinship terms with their values on the three dimensions. If a cell is left blank, the dimension is unspecified for that term.

|

Vertical |

Horizontal |

Gender |

|

|

mother |

–1 |

0 |

feminine |

|

daughter |

+1 |

0 |

feminine |

|

sister |

0 |

1 |

feminine |

|

aunt |

–1 |

1 |

feminine |

|

parent |

–1 |

0 |

|

|

grandchild |

+2 |

0 |

|

|

niece |

+1 |

1 |

feminine |

|

cousin |

0 |

2 |

Not All Languages Have “Aunts” and “Uncles”

Now let’s look at some of the terms that Lingala speakers use for kinship terms. Some of these are just like English, but others require different dimensions than are required for English. Lingala speakers use different words for siblings that are older or younger than ego and for aunts and uncles that are older or younger than their parents, but they don’t normally distinguish siblings or aunts and uncles by gender. We’ll refer to this as the “relative age” dimension. Lingala speakers also distinguish maternal and paternal aunts and uncles; we’ll call this the “parent path” dimension. Finally, Lingala speakers use the same words for grandparents and grandchildren; that is, at least some of the time they are concerned only with vertical distance, not vertical direction (earlier or later). The table below shows values on the kinship dimensions for some Lingala kinship terms.

|

Vertical |

Horizontal |

Gender |

Parent Path |

Age |

|

|

mama “mother” |

–1 |

0 |

feminine |

maternal |

|

|

tata “father” |

–1 |

0 |

masculine |

paternal |

|

|

nkoko “grandparent/grandchild” |

2 (+/–) |

0 |

|||

|

nkulutu “older sibling” |

0 |

1 |

older |

||

|

leki “younger sibling” |

0 |

1 |

younger |

||

|

mama–nkulutu “older sibling of mother” |

–1 |

1 |

maternal |

older |

|

|

tata–leki “younger sibling of father” |

–1 |

1 |

paternal |

younger |

Differences in kinship terms are more likely to be related to culture than differences in personal pronouns. That is, when a single term (such as Lingala nkulutu “older sibling”) groups different relatives together, we might expect that in the culture where the language is spoken, those relatives are treated similarly by ego. (I don’t know whether this is the case for Lingala speakers, however.) Words refer to categories, after all, and categories are a way in which people group the things in the world. Children growing up in a particular culture are learning the cultural concepts and the words simultaneously. Their experience with the culture should help them learn the words referring to cultural concepts, and their exposure to the words should help them learn the concepts. But little is actually known about how this sort of interaction works. In the next section we’ll consider the learning of the meanings of apparently simpler nouns, those referring to physical objects. Even here we’ll discover that there is considerable disagreement on how babies manage to master the words.

3.2 Adapted from Lexical Differences Among Languages (Gasser, 2015)

Watch this brief video on the translation challenges associated with the pronoun “you.”

Watch the video:

Video transcript:

Which is the hardest word to translate in this sentence?

Do you know where the pep rally is?

“Know” is easy to translate. “Pep rally” doesn’t have a direct analog in a lot of languages and cultures, but can be approximated. But the hardest word there is actually one of the smallest: “you.” As simple as it seems, it’s often impossible to accurately translate “you” without knowing a lot more about the situation where it’s being said. To start with, how familiar are you with the person you’re talking to? Many cultures have different levels of formality. A close friend, someone much older or much younger, a stranger, a boss. These all may be slightly different “you’s.”

In many languages, the pronoun reflects these differences through what’s known as the T–V distinction. In French, for example, you would say “tu” when talking to your friend at school, but “vous” when addressing your teacher. Even English once had something similar. Remember the old-timey “thou?” Ironically, it was actually the informal pronoun for people you’re close with, while “you” was the formal and polite version. That distinction was lost when the English decided to just be polite all the time.

But the difficulty in translating “you” doesn’t end there. In languages like Hausa or Korana, the “you” form depends on the listener’s gender. In many more, it depends on whether they are one or many, such as with German “du” or “ihr.” Even in English, some dialects use words like “y’all” or “youse” the same way. Some plural forms, like the French “vous” and Russian “Вы” are also used for a single person to show that the addressee is that much more important, much like the royal “we.” And a few languages even have a specific form for addressing exactly two people, like Slovenian “vidva.”

If that wasn’t complicated enough, formality, number, and gender can all come into play at the same time. In Spanish, “tú” is unisex informal singular, “usted” is unisex formal singular, “vosotros” is masculine informal plural, “vosotras” is feminine informal plural, and “ustedes” is the unisex formal plural. Phew! After all that, it may come as a relief that some languages often leave out the second person pronoun. In languages like Romanian and Portuguese, the pronoun can be dropped from sentences because it’s clearly implied by the way the verbs are conjugated. And in languages like Korean, Thai, and Chinese, pronouns can be dropped without any grammatical hints. Speakers often would rather have the listener guess the pronoun from context than use the wrong one and risk being seen as rude.

So if you’re ever working as a translator and come across this sentence without any context: “You and you, no, not you, you, your job is to translate ‘you’ for yourselves” . . . Well, good luck. And to the volunteer community who will be translating this video into multiple languages: Uh, sorry about that!

Exercise: Pick one of two options:

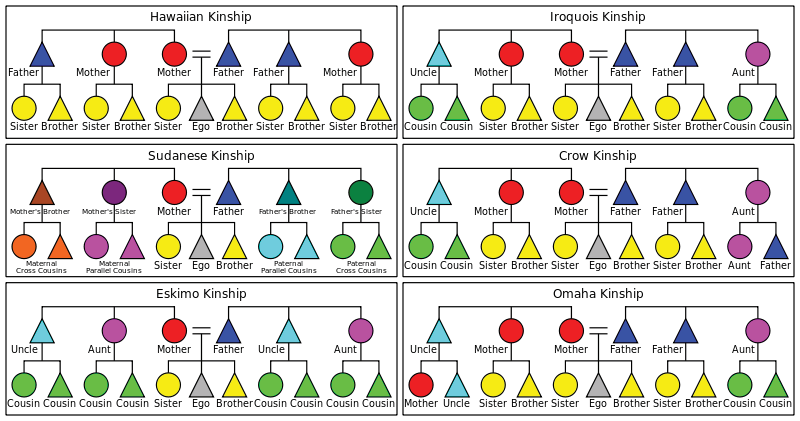

1. You want to work on kinship systems: Pick one of the following kinship diagrams (below), and apply it to your own family system, or that of a famous individual.

- Describe what you family system would look like in that society

- Specify who you would call an aunt, and who you would call a father in this system. Pro tip: For more fun, pick a kinship system you know nothing about, and that is far from your own.

- Specify what kind of social structure is implied in this system (Are elders important? Is it more patriarchal or matriarchal?)

2. You want to work on personal pronoun systems, and you want to do some research: Pick a language of your choice (it can be English, from a historical perspective, from Shakespeare and before, to today’s shifting pronoun systems).

- Describe that pronoun system, and explain how this pronoun system differs from the English one (you may want to create a table to do that)

- Explain what societal values and beliefs this pronoun systems implies (remember, we are working from a descriptivist, not a prescriptivist, perspective)

Here are some kinship systems to work from:

The diagrams show a two-generation comparison of the six major kinship systems (Hawaiian, Sudanese, Eskimo, Iroquois, Crow, and Omaha). Circle = female, triangle = male. Relatives marked with the same non-gray color are called by the same kinship term (ignoring sex-differentiation in the sibling/cousin generation, except where this becomes structurally relevant under the Crow and Omaha systems).

Note that in some versions of the Crow and Omaha systems, the relatives shown as “cousin” in the Crow and Omaha boxes of the chart are actually referred to as either “son/daughter” or “nephew/niece” (different terms are used by male ego vs. female ego). Also, in some languages with an Iroquois type of system, the relatives shown as “cousin” on the chart are referred to by the same terms used for “sister-in-law”/”brother-in-law” (since such cross-cousins—including remote classificatory cross-cousins—are preferred marriage partners). Similarly, the term for father’s sister can be the same as that for mother-in-law, and the term for mother’s brother the same as father-in-law.

The terms used for ego’s generation (i.e., the sibling/cousin generation) are usually considered critical for classifying a language’s kinship terms (some languages show discrepancies between ego’s generation patterns and first-ascending generation patterns). In anthropological terminology, the basic first-ascending generation patterns are actually called “generational” (shown in Hawaiian box), “lineal” (shown in Eskimo box), “bifurcate collateral” (shown in Sudanese box), and “bifurcate merging” (shown in the Iroquois, Crow, and Omaha boxes).

3.3 Are You Familiar with Memes?

This week’s discussion board will be a fun, practical activity requiring you to connect the concepts we have been learning to an Internet phenomenon.

Exercise: A. Read this brief article about the history and definition of Internet memes:

https://web.archive.org/web/20191106093130/https://www.howtogeek.com/356232/what-is-a-meme/

and this one on Chinese memes:

B. Now, create your own meme.

C. Connect your memes to at least one concept we have studied so far, and explain how this concept can help you understand memes as a sociolinguistic or ethnolinguistic phenomenon.

Further reading/watching if you are interested:

Supplemental article by Linda K. BÖrzsei: “Makes a Meme Instead: A Concise History of Internet Memes”

Watch the video:

Video transcript:

The chicken or the egg? Which one came first? This question has puzzled humanity for a long time. Linguists ask themselves a similar question. Do we think before we speak, or do we need language to shape our thoughts?

Two famous linguists have worked on what is called linguistic relativity. Edward Sapir and Benjamin Whorf have separately worked on this problem and came to the conclusion that the structure of one’s language affects the way in which we perceive the world. Our worldviews shape the linguistic structures of our respective languages, influencing thoughts and modeling linguistic behavior.

Whether linguistic relativity exists or not has been and still is heavily disputed amongst linguists. At the beginning of the 20th century in the early stages of linguistic relativity, Sapir and Whorf looked for clues to find out whether language determines thought or thoughts determine language. Around 1960 when the Universalist Theory of Language became popular, the relativity theory was heavily criticized since Universalists believed linguistic structures to be innate and all cognitive processes to be universal in human beings and therefore not influenceable by language.

Whorf’s most famous argument in favor of linguistic relativity was what he believed to be a major difference in the concept of time in Hopi languages compared to English. He claimed that Hopi speakers do not have the same temporal units, and therefore their culture was fundamentally different in its respect to ours. Of course this theory was disputed by Universalists. Their studies demonstrated that Hopi had different concepts of time than what Whorf had believed them to be and claimed that Whorf did not understand Hopi languages well enough.

Other relativists however countered, arguing that universalist misinterpreted Whorf’s work and tried to force Hopi grammar into models that were not fit for the structure of the Hopi language. In the 60s, a study was set up to discredit the relativistic approach. At that time it was believed there was no specific rule which determined between how many different colors a language would differentiate. Rather, differences were attributed to the culture in which languages were spoken.

Berlin and Kay examined the color terminology of different languages and found Universalist trends even though languages have different color terms certain hues are seen as more focal than others. Also, the choices of colors are not arbitrary. Instead there appears to be a hierarchy of colors. A language which recognizes the color blue also recognizes the colors black, white, red, green, and yellow, but not necessarily brown or pink. If speakers don’t recognize the colors green or yellow, the only colors that speakers of this language categorize are either black and white only or black, white, and red. These observations were seen as a powerful argument for the Universalist theory.

In the view of John Lucy, a relativist, is the word of Berlin and Kay had methodological shortcomings and was biased by the Western point of view. He conducted a different kind of experiment. He compared Mayan Yucatec and English grammars. He showed speakers of each language single objects and afterwards two different objects: one with the same shape but different material and the other one in the same material but differently shaped.

Which one of the two objects is more similar to the first one? English speakers tended to choose the object with the same shape, whereas Yucatec speakers or the material of the object as a more decisive factor. But why was there such a difference? Mayan Yucatec uses so-called classifiers, a specific linguistic device to categorize different nouns by shape. In his experiment, however, the questions were asked in a way that such classifiers did not apply. The objects were shapeless to the Yucatec speakers.

Recently, relativist studies have focused on bi- and multilinguals—people who speak two or more languages—to test the possibility of language shaping thought. But why bilinguals in particular? If different language has changed the way we think and perceive the world, bilinguals who speak two languages might think differently when language A is activated compared to when language B is active.

If we go back to the prior example of shape versus interior, how would a person who is brought up speaking both English and Mayan Yucatec answer the question, “Which object is more similar to the first one?” Linguists have found differences in the language use of monolinguals and bilinguals when describing colors, motion, time or space, but why is that? Aren’t bilinguals supposed to speak either language like a native speaker?

It is not that easy. One theory claims that language systems which are storing our minds are not entirely separated from each other. They overlap. Instead of the two languages being independent from each other, they are interconnected and share certain features. This phenomenon is called merging. If two or more language systems merge, it is possible that certain features in one language are dropped in favor of features of the other language. Merging of language systems has, for example, been found in semantics of Russian English speakers as well as in French speakers. Also, definitions of certain words and phrases can be broadened or limited. This is what linguists call boundary shifting, which will be shown with the following example:

A particular study on color perception in 2010 examined the change in the perception of the color blue in Greek speakers. English has one concept for blue. Greek has two: one describing light blue and the other one describing a dark blue. Two groups of Greek speakers were formed. Participants in the first group had lived in an English-speaking country for a much longer time than participants in the second group. The question was, would their perception of color differ from each other?

It did!

Greeks who had had a longer exposure to the English language learned to separate when it came to distinguishing the two types of blue they knew from their first language. So had English influenced their view of the world so that they did not see colors in the way they had before?

Do we think before we speak? Or do we need language to shape our thoughts? Is language in its structure already innate and does not influence our thoughts, or is it true that even though we are able to understand how others think we are not able to actually think in that way because our languages are different? What is your opinion? Do we think before we speak, or do we need language to shape our thoughts?

This is the total number of words existing in a given language.