Language, Worldviews, and Intercultural Communication

Learning Objectives

1. Identify and illustrate the specificities and challenges of intercultural communication

2. Analyze instances of cultural misunderstandings from an intercultural perspective

3. Define high- and low-context cultures

4. Explain how different understandings of politeness can shape intercultural communication and foster cultural misunderstandings

If you were to ask Russel Arent, author of Bridging the Cultural Gap, he would tell you that, “Intercultural communication is the sending and receiving of messages across languages and cultures. It is also a negotiated understanding of meaning in human experiences across social systems and societies.” This provides not only a concise definition but it also describes the importance that understanding has in intercultural interactions.

In this TedTalkX, Pellegrino Riccardi, a man who spent 27 years traveling the world to experience different cultures, refers to culture as, “A system of behavior that helps us act in an accepted or familiar way.”

Cross cultural communication | Pellegrino Riccardi | TEDxBergen https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YMyofREc5Jk

Intercultural communication is often used interchangeably with cross-cultural communication.

4.1 Intercultural Communication: A Dialectical Approach

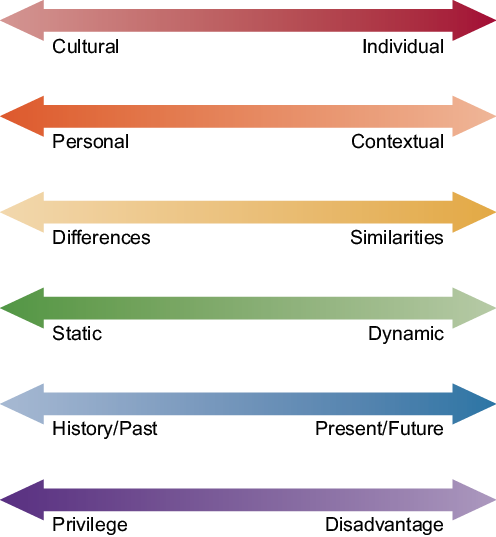

Intercultural communication is complicated, messy, and at times contradictory. Therefore, it is not always easy to conceptualize or study. Taking a dialectical approach allows us to capture the dynamism of intercultural communication. A dialectic is a relationship between two opposing concepts that constantly push and pull one another (Intercultural Communication 73). To put it another way, thinking dialectically helps us realize that our experiences often occur in between two different phenomena. This perspective is especially useful for interpersonal and intercultural communication, because when we think dialectically, we think relationally. This means we look at the relationship between aspects of intercultural communication rather than viewing them in isolation. Intercultural communication occurs as a dynamic in-betweenness that, while connected to the individuals in an encounter, goes beyond the individuals, creating something unique.

Holding a dialectical perspective may be challenging for some Westerners, as it asks us to hold two contradictory ideas simultaneously, which goes against much of what we are taught in our formal education. Thinking dialectically helps us see the complexity in culture and identity because it doesn’t allow for dichotomies. Dichotomies are dualistic ways of thinking that highlight opposites, reducing the ability to see gradations that exist in between concepts. Dichotomies such as good/evil, wrong/right, objective/subjective, male/female, in-group/out-group, black/white, and so on, form the basis of much of our thoughts on ethics, culture, and general philosophy, but this isn’t the only way of thinking (“Thinking Dialectically” 14). Many Eastern cultures acknowledge that the world isn’t dualistic. Rather, they accept as part of their reality that things that seem opposite are actually interdependent and complement each other. I argue that a dialectical approach is useful in studying intercultural communication because it gets us out of our comfortable and familiar ways of thinking. Since so much of understanding culture and identity is understanding ourselves, having an unfamiliar lens through which to view culture can offer us insights that our familiar lenses will not. Specifically, we can better understand intercultural communication by examining six dialectics (see Figure 4.1, Dialectics of Intercultural Communication).

For the purpose of this course, we will focus on the first four dichotomies.

The cultural-individual dialectic captures the interplay between patterned behaviors learned from a cultural group and individual behaviors that may be variations on or counter to those of the larger culture. This dialectic is useful because it helps us account for exceptions to cultural norms. For example, earlier we learned that the United States is said to be a low-context culture, which means that we value verbal communication as our primary, meaning-rich form of communication. Conversely, Japan is said to be a high-context culture, which means they often look for nonverbal clues like tone, silence, or what is not said for meaning. However, you can find people in the United States who intentionally put much meaning into how they say things, perhaps because they are not as comfortable speaking directly what’s on their mind. We often do this in situations where we may hurt someone’s feelings or damage a relationship. Does that mean we come from a high-context culture? Does the Japanese man who speaks more than is socially acceptable come from a low-context culture? The answer to both questions is no. Neither the behaviors of a small percentage of individuals nor occasional situational choices constitute a cultural pattern.

The personal-contextual dialectic highlights the connection between our personal patterns of and preferences for communicating and how various contexts influence the personal. In some cases, our communication patterns and preferences will stay the same across many contexts. In other cases, a context shift may lead us to alter our communication and adapt. For example, an American businesswoman may prefer to communicate with her employees in an informal and laid-back manner. When she is promoted to manage a department in her company’s office in Malaysia, she may again prefer to communicate with her new Malaysian employees the same way she did with those in the United States. In the United States, we know that there are some accepted norms that communication in work contexts is more formal than in personal contexts. However, we also know that individual managers often adapt these expectations to suit their own personal tastes. This type of managerial discretion would likely not go over as well in Malaysia where there is a greater emphasis put on power distance (Hofstede 26). So while the American manager may not know to adapt to the new context unless she has a high degree of intercultural communication competence, Malaysian managers would realize that this is an instance where the context likely influences communication more than personal preferences.

The differences-similarities dialectic allows us to examine how we are simultaneously similar to and different from others. As was noted earlier, it’s easy to fall into a view of intercultural communication as “other oriented” and set up dichotomies between “us” and “them.” When we overfocus on differences, we can end up polarizing groups that actually have things in common. When we overfocus on similarities, we essentialize, or reduce/overlook important variations within a group. This tendency is evident in most of the popular, and some of the academic, conversations regarding “gender differences.” The book Men Are from Mars, Women Are from Venus makes it seem like men and women aren’t even species that hail from the same planet. The media is quick to include a blurb from a research study indicating again how men and women are “wired” to communicate differently. However, the overwhelming majority of current research on gender and communication finds that while there are differences between how men and women communicate, there are far more similarities (Allen 55). Even the language we use to describe the genders sets up dichotomies. That’s why I suggest that my students use the term other gender instead of the commonly used opposite sex. I have a mom, a sister, and plenty of female friends, and I don’t feel like any of them are the opposite of me. Perhaps a better title for a book would be Women and Men Are Both from Earth.

The static-dynamic dialectic suggests that culture and communication change over time yet often appear to be and are experienced as stable. Although it is true that our cultural beliefs and practices are rooted in the past, we have already discussed how cultural categories that most of us assume to be stable, like race and gender, have changed dramatically in just the past fifty years. Some cultural values remain relatively consistent over time, which allows us to make some generalizations about a culture. For example, cultures have different orientations to time. The Chinese have a longer-term orientation to time than do Europeans (Lustig and Koester 128-29). This is evidenced in something that dates back as far as astrology. The Chinese zodiac is done annually (The Year of the Monkey, etc.), while European astrology was organized by month (Taurus, etc.). While this cultural orientation to time has been around for generations, as China becomes more Westernized in terms of technology, business, and commerce, it could also adopt some views on time that are more short term.

4.1 Adapted from “Intercultural Communication” (A Primer on Communication Studies, 2012)

4.2 Important Concepts for Understanding Intercultural Communication

If you decide to take a class on intercultural communication you will learn a great deal about the similarities and differences across cultural groups. Since this chapter is meant to give you an overview or taste of this exciting field of study, we will discuss four important concepts for understanding communication practices among cultures.

4.2.1 High and Low Context

Think about someone you are very close to—a best friend, romantic partner, or sibling. Have there been times when you began a sentence and the other person knew exactly what you were going to say before you said it? For example, in a situation between two sisters, one sister might exclaim, “Get off!” (which is short for “get off my wavelength”). This phenomenon of being on someone’s wavelength is similar to what Hall describes as high context. In high-context communication, the meaning is in the people, or more specifically, the relationship between the people as opposed to just the words. Low-context communication occurs when we have to rely on the translation of the words to decipher a person’s meaning. The American legal system, for example, relies on low-context communication.

While some cultures are low or high context, in general terms, there can also be individual or contextual differences within cultures. In the example above between the two sisters, they are using high-context communication; however, America is considered a low-context culture. Countries such as Germany and Sweden are also low context while Japan and China are high context.

4.2 and 4.2.1 Adapted from Understanding Intercultural Communication (Department of Communication, Indiana State University, 2016)

4.2.2 Speech Styles

Other variations in communication can be described using Gudykunst and Ting-Toomey’s four communication styles. Thinking about these descriptors as a continuum rather than polar opposites is helpful because it allows us to imagine more communicative options for speakers. They are not fixed into one style or another but instead, people can make choices about where to be on the continuum according to the context in which they find themselves.

This first continuum has to do with the explicitness of one’s talk, or how much of one’s thoughts are communicated directly through words and how much is indirect. Direct speech is very explicit while indirect speech is more obscure. If I say, “Close the window,” my meaning is quite clear. However, if I were to ask, “Is anyone else cold in here?” or, “Geez, this room is cold,” I might be signaling indirectly that I want someone to close the window. As the United States is typically a direct culture, these latter statements might generate comments like, “Why didn’t you just ask someone to shut the window?” or “Shut it yourself.” Why might someone make a choice to use a direct or indirect form of communication? What are some of the advantages or disadvantages of each style? Think about the context for a moment. If you as a student were in a meeting with the President of your university and you were to tell her to “Shut the window,” what do you think would happen? Can you even imagine saying that? An indirect approach in this context may appear more polite, appropriate, and effective.

Remember the fairy tale of Goldilocks and the Three Bears? As Goldilocks tasted the porridge, she exclaimed, “This one is too hot, this one is too cold, but this one is just right.” This next continuum of communication styles, succinct/exact vs. elaborate, can be thought of this way as well. The elaborate style uses more words, phrases, or metaphors to express an idea than the other two styles. It may be described as descriptive, poetic, or too wordy depending on your view. Commenting on a flower garden, an American (Exact/Succinct) speaker may say, “Wow, look at all the color variations. That’s beautiful.” An Egyptian (Elaborate) speaker may go into much more detail about the specific varieties and colors of the blossoms: “This garden invokes so many memories for me. The deep purple irises remind me of my maternal grandmother as those are her favorite flowers. Those pink roses are similar to the ones I sent to my first love.” The succinct style in contrast values simplicity and silence. As many mothers usually tell their children, “If you can’t say anything nice, then don’t say anything at all.” Cultures such as Buddhism and the Amish value this form. The exact style is the one for Goldilocks as it falls between the other two and would be, in her words, “just right.” It is not overly descriptive or too vague to be of use.

Remember when we were talking about the French and Spanish languages and the fact that they have a formal and informal “you” depending on the relationship between the speaker and the audience? This example also helps explain the third communication style: the personal and contextual. The contextual style is one where there are structural linguistic devices used to mark the relationship between the speaker and the listener. If this sounds a bit unfamiliar, that is because the English language has no such linguistic distinctions; it is an example of the personal style that enhances the sense of “I.” While the English language does allow us to show respect for our audience such as the choice to eliminate slang or the use of titles such as Sir, Madame, President, Congressperson, or Professor, they do not inherently change the structure of the language.

The final continuum, instrumental/affective, refers to who holds the responsibility for effectively conveying a message: the speaker or the audience? The instrumental style is goal- or sender-orientated, meaning it is the burden of the speaker to make themselves understood. The affective style is more receiver-orientated, thus places more responsibility on the listener. Here, the listener should pay attention to verbal, nonverbal, and relationship clues in an attempt to understand the message. Asian cultures such as China and Japan and many Native American tribes are affective cultures. The United States is more instrumental. Think about sitting in your college classroom listening to your professor lecture. If you do not understand the material where does the responsibility reside? Usually it is given to the professor as in statements such as “My math professor isn’t very well organized,” or “By the end of the Econ. lecture all that was on the board were lines, circles, and a bunch of numbers. I didn’t know what was important and what wasn’t.” These statements suggest that it is up to the professor to communicate the material to the students. As the authors were raised in the American educational system they too were used to this perspective and often look at their teaching methods when students fail to understand the material. A professor was teaching in China and when her students encountered particular difficulty with a certain concept she would often ask the students, “What do you need—more examples? Shall we review again? Are the terms confusing?” Her students, raised in a more affective environment responded, “No, it’s not you. It is our job as your students to try harder. We did not study enough and will read the chapter again so we will understand.” The students accepted the responsibility as listeners to work to understand the speaker.

4.2.2 Adapted from Survey of Communication Study (Laura K. Hahn & Scott T. Paynton, 2019)

Works Cited

Allen, Brenda J. Difference Matters: Communicating Social Identity. 2nd ed., Waveland, 2011.

Hofstede, Geert. Cultures and Organizations: Softwares of the Mind. London, McGraw-Hill, 1991.

Lustig, Myron W., and Jolene Koester. Intercultural Competence: Interpersonal Communication across Cultures. 2nd ed., Pearson, 2006.

Martin, Judith N., and Thomas K. Nakayama. Intercultural Communication in Contexts. 5th ed., Boston, McGraw-Hill, 2010.

—. “Thinking Dialectically about Culture and Communication.” Communication Theory, vol. 9, no. 1, 1999, pp. 1-25.