Chapter 4: Planning Class Sessions

Chapter Goal: To provide activity and engagement strategies that are easy to implement in your first semester teaching.

Bolizer (2022) found that most adjunct faculty learn by trial and error in the classroom, breaking down findings into three key areas of learning:

One, they learned about students’ lives and cultures, thereby discovering the richness and range of student identities. Two, they described how through seeking to represent the subject matter to students, and by hearing students’ own representations of that subject matter, they came to see that subject matter in new ways, thereby gaining new insight into the subject matter itself. And, third, some participants learned even more: they came to see connections between their subject matter and their students’ lives, thus unearthing students’ sociocultural ways of knowing. These findings reveal the possibility of college classrooms being a place of growth in which both adjunct faculty and their students are learners (p. 88).

In this chapter we will walk through different strategies to help you build community, motivate students, review your syllabus, and assure your course assignments and assessments are aligned with the learning outcomes for your class. Active learning is also a key to keep students engaged and to increase their retention of information. We will share several simple, easy to implement active learning strategies you can integrate into your classroom. Lastly, we talk about that often dreaded but every so vital learning tool, the group project, including strategies to help you use it successfully in your class.

What To Do on the First Day of Class

Icebreaker and community building activities

Research suggests that community is an important mediating factor for learning. For example, Summers and Svinicki (2007) identified a connection between student motivation and community in the classroom, particularly in cooperative learning environments. And, instinctually, this makes sense. When we are accountable and connected to others, we find that we are more motivated to participate.

In-Person Classes

A Google search will reveal no shortage of icebreaker options. Be sure your activity is not something that would be uncomfortable or over-exposing for students to share. Also be aware of excluding topics that expose privilege. For example, “what high school did you attend” can expose socio-economic background, or “what pets do you have” is limiting for those without pets. Also consider how the icebreaker could be anchored in the class content such as asking what interested them in signing up for the class, or which of the topics on the syllabus most interest them.

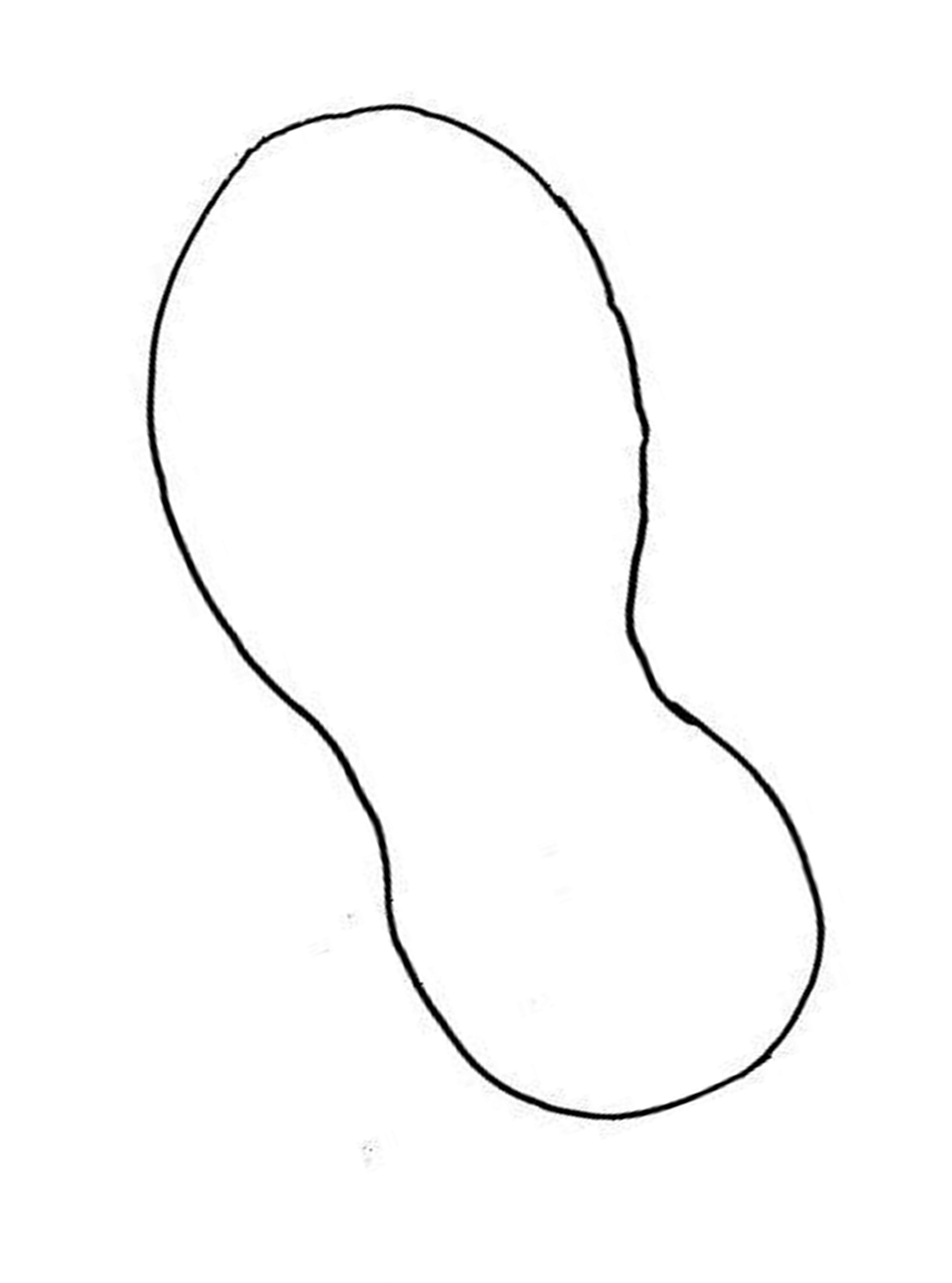

Example 1: Sole Mates

Contributed by Linda Gaither, Educator Preparation and Leadership

In this activity students fill in the sole and then walk around the class and find their “Sole Mate”. You can collect and use the “heel” question in your next class meeting. Linda uses this in her methods course as a “ready to use with high school” activity. For the college level she adjusts to questions that deal with how she can help students be successful this semester.

Student Instructions: Using the graphic below, indicate the following items in the different areas and post on our discussion board.

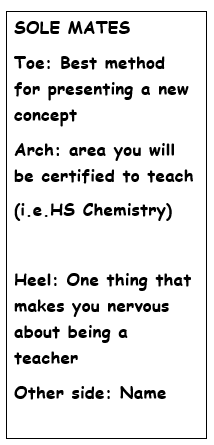

Example 2: Getting to Know you Diagram

Contributed by Linda Gaither, Educator Preparation and Leadership

Example 3: 10 Steps to Effective Listening

Contributed by Sarah Coppersmith, College of Education and Honors College

This activity will work as an ice-breaker or short activity in face-to-face settings as well as online courses and has proven useful in both contexts. The document includes “10 Steps to Effective Listening” so it easily breaks into 10 parts to be assigned to individuals and/or groups.

The goal is to review good communication strategies. When using the activity with in-person courses, participants could be assigned one of the steps to review, practice, and model to the group, such as how to meet the goals through a simple role-play or discussion. If using paper handouts, the document may easily be cut into the 10 steps for in-person work or re-designed for online groups. Depending on the size of the class, groups may be arranged with at least two people, to larger groups as needed. In the end, practicing the steps and modeling for others should help everyone review the basics of good listening and communication in-person or online.

See full example here: https://tinyurl.com/SuvivalGuide1

Online Classes

The Community of Inquiry (CoI) framework provides additional theoretical backing for the importance of community in the online classroom (Garrison et al., 2001). Within the CoI, social presence is most relevant to the engagement aspects of the classroom. Social presence is your students’ ability to be their authentic self within the course. Icebreakers can be a great way to build social presence for students into an online or blended course where interactions may be more limited. For further information about the CoI model, including assessment tools, you can visit The Community of Inquiry website https://www.thecommunityofinquiry.org.

For online asynchronous courses, those where you do not meet together at any specific date or time, LMS discussion boards or collaborative editing documents such as Google Docs can be used to replicate many of the in class examples.

The following example prompt, provided by Linda Gaither, is for teachers in training but could easily be adapted to many other disciplines.

|

Online Discussion: Word Cloud–Teaching Philosophy The purpose of this discussion board is for you to share your thoughts on your teaching philosophy–how you see yourself in the role of teacher– in the form of a word cloud with the community of learners in this course. After you make a list of key phrases, stating your current view of your teaching philosophy; you use the link to Wordle or Tagxedo tools provided (or a different program that makes word clouds) and paste in your words. Use the program to edit your “cloud” into a form that you like. Then post that cloud to the discussion board. Label the cloud: “Your last name teaching philosophy” (i.e. Gaither’s Teaching Philosophy) in the subject area and use “ctrl-v” to paste your word cloud in the box. Hit submit to save the cloud. This initial post needs to occur by Thursday (see the agenda for exact date) 11:59 P.M. CST. Along with your word cloud please answer the following questions in the comments section of your post: 1. Briefly tell us about your plans as an educator. What subjects will you teach, are you already teaching, are you in practicum one? 2. What or who influenced you to go into education as a career? 3. If you could list one “fear”-“concern” you have about being a teacher, what would it be? After others have posted their “Teaching Philosophy Cloud” you need to view at least 2 other clouds (but please consider responding to more), select words from that cloud that are not in your cloud, then post them in a reply and tell why they also represent your teaching philosophy. These two responses need to be completed by Monday (See agenda for exact date) by 11:59 P.M. CST. |

Reviewing the Syllabus In Class

In addition many faculty have found creative ways to build engagement activities around their syllabi. Below are a few common options we frequently use.

Syllabus Quiz: A quiz that asks students about key items or policies you want to highlight from the syllabus to assure they have read it and understand it. Follow up with an opportunity for students to ask questions about areas where they are unclear.

Syllabus Scavenger Hunt: An opportunity to look for specific elements in your syllabus you wish to highlight. You might opt to have them do this online before class or in-class as a small group activity.

Annotating the Syllabus: There are many great tools that allow students to highlight and comment on documents (e.g. Hypothes.is, Perusall, Google Docs, Microsoft Teams). Jen McKanry loves creating a discussion the first week of her online class where students use an annotation tool to identify five areas they are excited about and three areas where they have questions. And then she has them answer each other’s questions all right on the document. For any questions they cannot answer themselves she follows up with a short video announcement with the answers.

Challenge the Syllabus Activity: For Jen’s in-person class, she has a day-one activity where students get into pairs and review the syllabus together. They are tasked with identifying three areas where they are unclear on something and then share that back out with the rest of the class. For larger classes you might have each group share one question without repeating what has already been asked. Continue around the room until all questions are exhausted.

Break the Syllabus Activity: One very creative faculty asked students to break the syllabus. What can you do to break down the syllabus into its most important components?

However, no matter how hard you try to set expectations and an understanding from the beginning, sometimes students will not see the value of your course right away. It might sink in throughout the semester or maybe not until later classes. If you are lucky you get to see that moment of enlightenment and all your hard work pays off.

Scenario

Considering Learning Outcomes

Many of us underestimate the power of learning outcomes, or objectives (see chapter two for more on writing learning outcomes). They represent the skills students should have upon completion of the course. Therefore it is important to align what we are teaching and assessing with these outcomes. As you design your class activities and assessments, consider building a grid, such as in the following example, to help you and your students understand the value of each course component. This can also be helpful when you are trying to pare back content. Consider what contributes most to students’ progress toward class outcomes.

The following assignment alignment example comes from Jen McKanry’s online information literacy general education course.

|

Upon completion of this course you will be able to… |

Week 1 |

Week 2 |

Week 3 |

Week 4 |

|

CLO1: Analyze and evaluate information for objective accuracy, valid use, or appropriate construction. |

Discussion board on Chapter 1 |

|

Discussion board on Chapter 2 |

Conduct a critical analysis of a social media post related to your topic |

|

CLO2: Use modern technologies to research, retrieve, synthesize, construct, and present information for academic disciplines. |

Select a topic of focus for the semester |

Annotated Bibliography on your topic |

|

Conduct a critical analysis of a social media post related to your topic |

|

CLO3: Apply digital literacy skills that allow for further specialization in your chosen major/discipline to keep up with continuous evolutions in information construction. |

|

|

Create a PowerPoint presentation on your topic |

Conduct a critical analysis of a social media post related to your topic |

CLO = Course-level outcome

Outcomes are often determined at the program level as each class contributes to the bigger picture of the student learning experience in their degree program. Before altering course-level learning outcomes, check with your department chair.

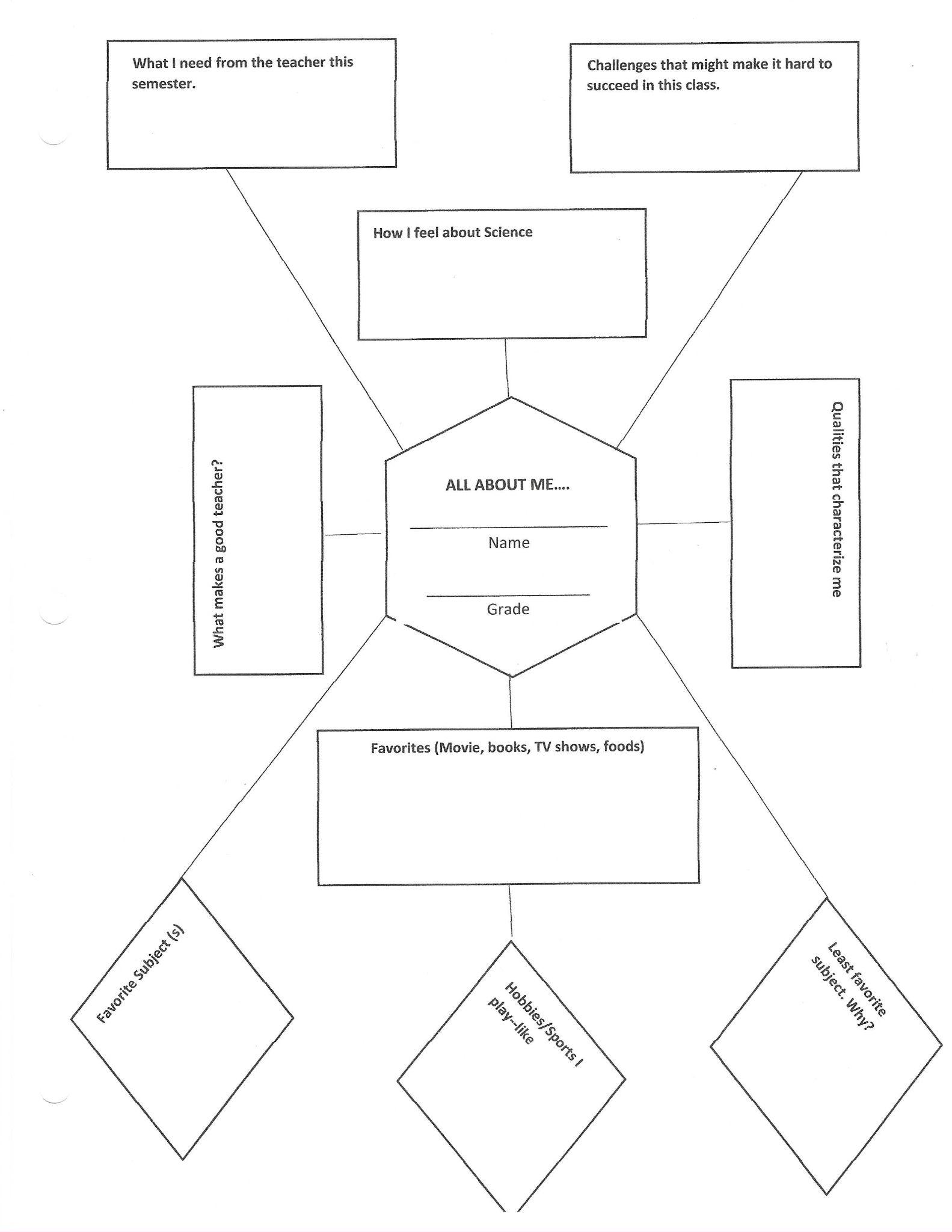

Planning Class Sessions

You are likely also wondering what you will do to fill your class time. Or maybe you are thinking you will just lecture and students will magically absorb everything you are saying. One thing we learn quickly in the classroom is that lectures are not always a very effective learning strategy. Think back to your own classes. What stuck most with you? I was likely when you were engaged in the learning. Also consider the human capability for attention. At most we are able to focus for six minutes at a time. Bunce et al. (2010) found that in longer lectures that time decreases throughout the class period. Consider “resetting” students’ attention clock by breaking up your lecture by engaging students at least every 6 minutes, even if it is just to have them stand up and stretch.

We call this active learning and it can be as simple as a Think-Pair-Share (see below) or as elaborate as a field trip to see things in situ (in the original place linked with your subject matter). Below are a few of our favorite active learning strategies that are easy to implement in the classroom. For more examples see the Active Learning Library https://teaching.tools/activities. Use the filters to find exactly what you need.

Think-pair-share (TPS)

This common active learning strategy can easily be implemented in any class, large or small, and requires little preparation, often even working great on the fly. It can typically be done in five to 15 minutes of class time.

Step 1: Think – have students reflect on a short question prompt. This step is important to help students organize their thoughts. It is also especially important for quieter students who might need time to process before sharing their thoughts.

Step 2: Pair – have students turn to a partner nearby. Sometimes this is a group of 3 depending on the seating and number of students in your class. Have them discuss their response to your prompt. Since sharing in small groups is lower risk for students it can be a powerful way to get everyone engaged.

Step 3: Share – your pairs share their takeaways with the whole class. This often involves just a few pairs sharing out or all pairs sharing just one takeaway each until all points have been exhausted.

Muddiest point

This can be used as an entry or exit ticket to class, in the middle of class, or as an online survey and can be a great way to get a pulse of where students are struggling using no more than five minutes of class time. Ask students to write down the most difficult or confusing part of a lesson, lecture, or reading. Be sure to allow yourself time to review their responses and adjust your next class to address areas most students are struggling with.

Fist to five

Fist to five can be a great way to do a quick informal poll in the classroom to check comprehension, build rapport, or promote student well-being. It also provides a quick way to involve everyone in the class, even those who might be hesitant to speak up. Take a quick informal poll by having students use their fingers to rate things like their general mood, support for an idea, their level of preparedness, or how challenging the assigned reading was. If most students indicate they are unprepared, you can modify the lesson plan on the spot.

Values activity

It can be powerful to have students identify their values and connect them to the content you are teaching. The following example of an in-person values activity was contributed by Lynette McAllum from her first year experience course.

We start with folding a piece of paper to get 16 squares layers. I do it with them so I am on pace with them as they are folding. After this I read a scenario and tell them they have to list their favorite people, items they want to possess, etc. on each of the folds of paper. Then I read them a story in which at each phase they have to give up one of the items they identified. At the end they only have one item left. I ask them “Did you think this was going to be your last item?” It can be so interesting to see what they wind up with and how they make different decisions. And often they are surprised by what they still have. For me, each time I do this activity I always wind up with my TV of all things!

Planning Group Work

We know students may dread group work, and as faculty we may dread the complaints about group work. But let us take a moment to dissect why group work is so detested. We know it is important for students to build collaboration and negotiation skills and learn how to divide tasks up and work together. But often what happens is little guidance is given to teach students how to do these tasks. The result is often that one student does the bulk of the work, resents the other students for not contributing, and vice-versa the other students feel one member of the group dominated the project.

Consider instead, providing students step-by-step guidance on how to work together. Do not assume this is a skill they will just figure out on their own. The following example from Plotts (2022) provides one possible option for a spaced out process.

Step 1: Build in time for the group to get to know each other including collecting an inventory of the skills and values of each member of the group.

Step 2: Have the group work together to create a working contract. Providing a form or worksheet for this can help guide the process (see example in Appendix E).

Step 3: Give them the project direction and parameters. Note this is intentionally held until this stage to reduce bias in previous stages. Be sure students have ample time to collaborate. Where possible provide in-class time to work together. If this is not possible or the course is online, be sure deadlines allow the group to work around each other’s commitments. Short deadlines pretty much guarantee the process will fall apart.

Step 4: Build in intermediate deadlines. Have them submit a draft or early outline of the project or an annotated bibliography of the resources they plan to use. This helps prevent last-minute cramming.

There are research-based resources available for having groups evaluate each others’ participation, such as those found at Vanderbilt University’s “Team Based Learning Center” examples for team evaluations.

Example of a peer review and collaborative writing assignment

When possible, consider building peer review and collaborative writing into the writing assignment. This strengthens many of your students’ writing skills and takes the onus of some of the work off of you. The following writing project example was shared by Ashley Cox from her criminology class and could work for an in-person or online class.

Scenario

Example of in-class collaborative writing

The following example, provided by Matia Mwase from his heath and physical education course for students planning to work in the K-12 environment, helps students actively engage with textbook content in a real world scenario, and develops critical thinking skills, as well as group collaboration and writing skills. This was completed in an hour and ten minute class with a small group of students.

Scenario

I wanted the students to write a paper about planning a physical education resistance training program for children. I started by asking students to get into pairs and come up with a short activity they could perform in front of the rest of the class. After performing their activities I had them each state their current job or planned career was. The majority confirmed they were hoping to be a personal trainer, physiotherapist, etc. Many were already working in a related job. Then I asked them to act, not as students but as experts and for each pair to develop a section of a paper as if they were already in this career. I randomly gave them group names like a, b, c, d. And each group got a different question to work on. The first was the benefits of resistance training. The second was factors to consider to have an effective resistance training program. The third was features or characteristics of an effective resistance training program. And the last was common injuries, their causes, and the preventative measures. They were free to consult the textbooks and other reference materials. But I also wanted them to include content from a realistic setting.

Then I asked them to imagine they had been invited to present such a paper to the school district. As each group presented, the class asked questions and gave suggestions that helped strengthen the section. Sometimes, but not often, I had to chime in and ask a few additional questions. After all sections were presented, as a whole class we decided the order the sections should be in. Then I asked if anything additional was needed, and they suggested adding a conclusion section. Now we have essentially written a chapter of the textbook. I encouraged them to add in references and use this paper to present to their school districts in the future to help promote resistance training programs in their schools. – Matia Mwase, University of Missouri-St. Louis, Heath and Physical Education

Building Student Motivation

Scenario

As much as we would love to believe our students are excited about our class and motivated to work hard and learn, unfortunately that is not always the case. Students come to college for a variety of reasons and are often juggling complex work and home life situations in addition to their classes. Due to financial aid requirements students may not have an option to study part-time instead of full-time despite everything on their plates. Student motivation can also depend on the course and level you are teaching. For example, a student might be less motivated in a general education course than in a course in their major. Graduate students with a more focused curriculum and more college-level experience might also be more focused and motivated than an undergraduate student. But there is much you can also do to help impact student motivation. Consider the following strategies which build upon Knowles et al. (2005) principles of adult learning theory.

A few examples of motivation strategies include:

- Build in opportunities for success early in the class.

- Build in student choice where possible.

- Make sure all assignments are meaningful and necessary for success and not perceived as busy work (see the TILT model under the Managing your Time for Success section in this chapter).

- Help students connect their work effort to tangible outcomes in their careers or life.

- Check in with students when they miss class or miss an assignment. This lets them know you care and you notice these things. Your LMS often has tools to help expedite this.

- Build a community in the course through: class or small group discussions, building fun into class activities, or assigning accountability partners to check in on each other.

Do not take it personally

Most importantly do not take it personally when students choose to prioritize things other than your class. When students miss class or do not submit assignments it does not mean they do not care. Just like we often have to, it could mean they are making difficult choices in what they prioritize in their own lives.

Consider students’ existing experience

We also must recognize our students are not empty slates when they come into our classroom. This is especially true in today’s college environment where so many of our students do not come to us directly from high school, but rather have complex and diverse lives including work, military or volunteer experience, and often families of their own (Afeli et al., 2018; Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, 2016; Redford, 2017). We need to think about how we can build on the rich experience, strengths, culture, and background our students bring to class as well as how to help enrich their learning through building connections between course content and those experiences.

One way to do this is by using culturally responsive teaching in your course design. Being culturally responsive simply means integrating strategies, interventions, or responses that incorporate students’ cultural frameworks within the learning environment (Plotts, 2022). And yes, this applies to STEM classes too such as Math, Chemistry, etc. Regardless of what you are teaching, acknowledging your students as individual and unique people is critical. Using culturally responsive strategies has been found to not only increase motivation, but also decrease student stress.

Scenario

In the course that I teach it is essential that the students understand why and how the course is necessary for their selected field of study. I also adapt class sessions to meet the needs of students, addressing their misconceptions (in relationship to hard-to-discuss topics), and encouraging discussions about confusing issues. I use culturally responsive teaching strategies to encourage bias-free understanding. This can lead to rich learning experiences. The curriculum also provides new information that can provide a deeper understanding and promote critical thinking, encouraging students to go beyond their current knowledge of a topic.

Culturally responsive teaching techniques also help me support and focus on students’ strengths and encourage them to build on their strengths. I do this by providing students with positive feedback and encouraging additional constructive and critical thinking. By using this approach, I have found that I, and the students, create a classroom culture that supports the various learning abilities, and integrates new learning with previous knowledge or learned concepts. – Ida Casey, University of Missouri-St. Louis, Education Sciences and Professional Programs

If you are interested in learning more about culturally responsive teaching, we recommend the book by Courtney Plotts, Cultural Intentions: An Evidence-based Framework for Applications of Cultural Responsiveness in Education (2022), or check out her website https://neurocultural.org/.

Building in student choice

Adult learners like to have some control over their learning. In your course design this might be something small like getting to choose a topic of interest for a paper or presentation, or choosing which group they work with for a group project. Some faculty build in multiple assignment options such as choosing between an exam or a paper for a final. Students have different skills and comfort levels so this helps them customize the experience. For example a student with test anxiety might really appreciate the option to write a paper. Where a student with dyslexia may struggle writing and be better able to express their knowledge through a multiple choice exam. As always, anchor your decisions in your course outcomes. What is most important for you to know that your student has learned or mastered? Are multiple ways students might express that knowledge, skill, or ability (CAST, 2024)? Keep in mind, to prevent bias or preferential treatment, if you offer options or flexibilities to one student you must offer that same option to all students, unless it is an accommodation for a specific student approved by your institution’s disability access services office.

Scenario

Our recommended resource to learn more about building in choice is the website, “Embracing Choice” designed by Dr. Jo-Ann Thomas, one of our colleague Sarah Coppersmith’s former doctoral students: https://www.embracingchoice.com/

Dealing with incivility

Unfortunately, despite your best efforts, sometimes students can be downright rude. In the literature, this is often called student incivility which includes a variety of behaviors that lead to a negative learning environment (Hudgins et al., 2023). Interestingly, though students and faculty do not always hold similar perceptions of incivility, research suggests they may have similar thoughts about how to address it (Hudgins et al., 2023; Campbell et al., 2020).

Proactive strategies you can plan ahead of class:

- Set early expectations for appropriate norms and standards of communication for your classroom or online learning environment.

- Include an incivility statement in your syllabus.

When faced with student incivility, consider these strategies:

- Talk with your course steward or department chair about policies and resources for referral.

- Try to meet separately with the student outside of class. We recommend this being in a public setting or with your office door open and colleagues nearby. Consider that there might be other external forces influencing their behavior. Ask about what other resources might your student need to be successful, counseling, tutoring, etc.

- Keep the focus of the conversation about the behavior and not the student.

- Make sure they understand their behavior is not acceptable.

- If you have tried to redirect unsuccessfully, report the student to your academic integrity office, or if necessary, your Title IX officer.

Scenario

Canceling Class Sessions

Just as students are absent, there may be times you will not be able to make it to class. Consider the following steps to plan for success ahead of needing to cancel class or identify an alternative to fill in for you.

- Sign up for campus alerts. Find out how to get campus alerts in case of a campus closure (weather, power outage, etc.). Most universities have automated systems to send emails and/or text when such situations occur. Make sure to sign up early.

- Include a “Plan for the Unexpected” in your syllabus. How will you communicate to students if your class has to pivot online or be canceled? How should students let you know if a crisis comes up for them?

- Know your department’s policy on canceling class. Find out what your department’s policy is for canceling class. Is there a limit on how many classes you can miss? Accrediting agencies often have requirements for contact hours so it is important to learn details.

- Know who can cover for you. Confirm with your department chair if you are allowed to ask someone else to cover the class for you in an emergency. For safety reasons there are typically requirements that person be staff or faculty affiliated with your campus. Campuses often have Don’t Cancel Class programs where someone from areas such as the library or wellness center can lead a class.

- Know your remote options. Find out what your department’s policies are for switching a class to remote using a webinar tool such as Zoom. In the event of a campus closure this is often a convenient option. However, if you are the only one switching your class it can cause hardships for students who might have in-person classes before and after making it hard to find a safe and quiet location to join remotely. Also be aware that students might not have equipment for such shifts or may have other obligations in emergency situations. For example if there is a major weather event in the area, students might have to suddenly care for their own children or siblings who would normally be in daycare or school themselves.

- Know your asynchronous options. Again, this is where being familiar with your campuses’ LMS is very helpful. Even if you are not using more advanced features such as discussion boards for your class, it can be helpful knowing how to set one up quickly in the case of an emergency. Maybe consider having a generic discussion board ready to publish just in case you need it.

Balancing Flexibility and Structure

Scenario

We all want to be that faculty who helps a student be successful. And when students come to you with stories of struggle you naturally want to do what you can to help. But when is flexibility on an assignment deadline, format, or modality helpful and when it is detrimental to both you and your students? Garcia (2020) provided the argument that course flexibility and structure do not have to be in opposition to each other, especially if you plan ahead in your policies, and rigor can be maintained.

- Are there alternative, equivalent ways a student could demonstrate learning? This might mean a paper or presentation instead of an exam.

- How flexible can you be in your deadlines before students get so far behind they are unable to catch up? What is reasonable for you to grade outside your normal timeline? This, of course, also depends on the class content and length. A common policy for a 16-week course is that assignments can be no more than one week late and often include a penalty, for example 10% of the total assignment grade.

- What constitutes a severe crisis? When drafting policies be careful of any language that puts the judgment in your hands instead of the student’s to determine when additional flexibility will be allowed. Do you really want to be responsible for determining how severe a family death, illness, or other crisis is before it triggers exceptions to your policies? A common strategy is to use “tokens” that students can choose when to apply. For example, you might allow two tokens per student to use on any assignment except the mid-term and final. The token might give them extra time on an assignment or the ability to skip an assignment without penalty.

Garcia (2020) suggests the following advice for balance:

1. Clarify assessment strategy:

-

- Clearly define the parameters for evaluating student work, so students understand the expectations.

- Use multiple lower-stakes assessments throughout the course. These can include quizzes, short assignments, or participation activities.

2. Build in multiple deadlines:

-

- Stage course projects by breaking them into smaller components. This allows students to receive feedback early and correct any misconceptions. Multiple interval deadlines also help students stay on track and not fall behind or wait until the last minute to complete larger assignments.

3. Provide open communication and feedback:

-

- Welcome, even encourage, student questions and concerns. Address them in class or through announcements.

- For larger classes consider a Q&A discussion board in your LMS open all semester. Award extra credit to students who answer other’s questions. This can not only lighten the work of responding but also generate a resource students can go to for frequently asked questions.

- Consider instead of asking “Are there any questions?” ask “What questions do you have?” promoting the idea you expect questions.

- Share responses with the entire class. If one student asks a question, others likely have similar thoughts.

4. Offer proactive accommodations:

-

- Do not wait for students to request accommodations. Some may hesitate due to privilege or discomfort.

- If one student needs an accommodation (e.g., extra time), consider offering it proactively to others who may benefit.

Keep in mind, to prevent bias or preferential treatment, you should offer the same options to all students, unless it is an accommodation for a specific student approved by your institution’s disability access services office.

Often in teaching we are so busy we do not take a moment to reflect on our own learning and growth. A great strategy many teachers use is a teaching journal to make notes about your experiences and ideas you have for future iterations of a class. We will end each chapter with reflection questions you might want to respond to in your teaching journal.

What teaching strategy were you most satisfied with this semester and why?

What new teaching resources or strategy libraries did you discover this semester?

What would you like to try or tweak next semester on your continuous improvement journey?

Chapter 4 References

Afeli, S. A., Houchins, T. A., Jackson, N. S., & Montoya, J. (2018). First generation college students demographic, socio-economic status, academic experience, successes, and challenges at pharmacy schools in the United States. Currents in Pharmacy Teaching and Learning, 10(3), 307-315.

Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (2016). Postsecondary success: Today’s college students. https://postsecondary.gatesfoundation.org/what-were-learning/todays-college-students/.

Bunce, D. M., Flens, E. A., & Neiles, K. Y. (2010). How long can students pay attention in class? A study of student attention decline using clickers. Journal of Chemical Education, 87(12), 1438-1443. https://doi.org/10.1021/ed100409p.

Campbell, L. O., Tinstman Jones, J., & Lambie, G. W. (2020). Online Academic Incivility Among Adult Learners. Adult Learning, 31(3), 109-119.

CAST. (2024). Universal Design for Learning Guidelines version 3.0. http://udlguidelines.cast.org.

Garcia, H. (2020, May 5). Flexibility and structure in course design: You don’t have to choose. Ecampus Course Development & Training. https://blogs.oregonstate.edu/inspire/2020/05/05/flexibility-and-structure-in-course-design-you-dont-have-to-choose/.

Garrison, D. R., Anderson, T., & Archer, W. (2001). Critical thinking, cognitive presence, and computer conferencing in distance education. American Journal of Distance Education, 15(1), 7–23.

Hudgins, T., Layne, D., Kusch, C.E., & Lounsbury, K. (2023). An analysis of the perceptions of incivility in higher education. Journal of Academic Ethics 21(2):177-191. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10805-022-09448-2.

Knowles, M.; Holton, E. F., III; Swanson, R. A. (2005). The adult learner: The definitive classic in adult education and human resource development (6th ed.). Elsevier.

Plotts, C. (2022). Cultural intentions: An evidenced-based framework for applications of cultural responsiveness in education. DBC Publishing.

Redford, J. (2017). First-generation and continuing-generation college students: A comparison of high school and postsecondary experiences. National Center for Education Statistics. https://nces.ed.gov/pubsearch/pubsinfo.asp?pubid=2018009.

Summers, J. J., & Svinicki, M. D. (2007). Investigating classroom community in higher education. Learning and Individual Differences, 17(1), 55–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2007.01.006.

The Community of Inquiry. (n.d.). A CoI for the CoI. https://www.thecommunityofinquiry.org/.

An activity focused on helping students get to know each other and build community.

Teaching that focuses on student participation rather than passive translation of information from teacher to student.

In education, a less formal way to quickly assess student understanding by asking them to indicate using one hand with a fist representing complete lack of understanding and five fingers representing complete understanding.

A student's desire to learn or complete coursework. Motivation can be influenced by internal and external factors.

The strategies that an educator integrates students’ cultural frameworks in the learning environment.

Rude, impolite, or offensive behavior from students.