Chapter 1: Why I Teach

Chapter Goal: To reflect on what brings many of us to teach and how we can use that motivation to sustain us at points of struggle on our pathway.

Scenario

The fictional scenario above is common in academia. In fact, several of us on the author team for this book have experienced something very similar. A last-minute request, last-minute syllabus, and subsequent commitment to teach a challenging course proved demanding throughout the semester, but in the end, led to a long-term service to the department. Why teach in these demanding situations? Below are a few reasons, ideas, and tips to help answer that question.

Much has been written about the challenges faced by adjunct faculty across the country and the impact on job satisfaction and well-being (Ambrose et al., 2005; Danaei, 2019; Reybold, 2005), and often in a negative light. While not ignoring current issues, our focus includes positive, constructive, and satisfying facets of teaching which draw people to the profession. In addition we provide suggested resources, tips, and models. We present examples from our own perspectives, along with findings from our small IRB approved research survey giving glimpses into the engaging aspects of teaching.

Imposter Phenomenon

There are a variety of ways adjunct faculty engage in teaching, most often working full-time while also teaching. Others include those retired and teaching as a second career, looking to enter academia, or some who like the position flexibility of piecing together full-time teaching work by teaching classes at multiple institutions (see chapter two for a more detailed description of types of adjunct faculty). However, an important element to be aware of when teaching in academia is the impostor phenomenon, as researched by Ménard et al. (2023), also called the imposter syndrome (Brems et al., 1994). From this research we know that imposter phenomena are common amongst faculty, and even students, regardless of gender, race, ethnicity, or identity. Faculty across the board have reported negative feelings, such as self-doubt, and perceptions of being inadequate. These can be triggered by interpersonal interactions or situational factors. One participant in the Ménard et al. study described one such trigger, “I made a typographical error in an email I was sending to faculty, and one faculty member in particular ‘replied to all’ and basically made fun of me to everyone in the department” (p. 109). Another shared, “I sometimes feel excluded from important meetings, etc. because I am not an ‘academic’” (p. 110). And student interactions were identified as particularly triggering:

I often felt like an impostor in front of the classroom teaching at first, because I would sometimes be challenged by white male students who took exception to something I said… I felt small and frightened when this happened, and it had a lasting impact on my self-confidence (p. 110).

Even when those around us are supportive, negative self-perceptions can also be triggering. One participant in the Ménard et al. (2023) study wrote:

My training was not the typical path within this field, and as a result I felt inadequate as an instructor in the program because I perceived there were certain paradigms, expectations, or manners of teaching that I was not providing to students but were assumed as common knowledge to all faculty (p. 111).

Part of the challenge arises from the competitive nature of academia. Ménard et al. (2023) offers some solutions. The first is awareness, so as you reflect on your role, be aware that this is a real phenomenon that can arise, and that there are ways to seek support when needed. For example, a supportive environment can be built with open discussions, peer support networks, training, and mentorship. Consider looking for campus resources such as the center for teaching and learning or academic technology support who often house these programs. However, the first step is to recognize this may be an issue, realizing you are not alone in this challenge of teaching in academia.

Additional strategies include preparing ahead for new tasks or roles, leaning on supportive friends and trusted colleagues, and directly challenging one’s thoughts and beliefs including adopting a mental attitude recognizing one’s self-worth (Ménard et al., 2023). We hope through the stories in this book we can dissuade some of that sense of isolation or fear of failure that often contributes to the imposter phenomenon.

The Essence of Teaching

In this section we discuss elements we have found to be helpful in finding success with teaching; why we engage in it as adjunct faculty; some challenges and ideas; and what keeps us coming back. To help us answer this question, we conducted a short survey to gather perspectives from our colleagues’ experiences. Below is a summary of their responses and some of the demographics of our survey.

For the initial pilot of our survey in Spring 2024, we limited participation to adjunct faculty at the University of Missouri-St. Louis, the institution at which the study leads were employed. We received 25 responses. Demographic information for respondents is available below.

Survey respondent career stages. Respondents indicated varying stages of their career in teaching, with serving as an adjunct in addition to a full-time job being the most common.

I work another job full-time and teach part-time. (6)

I am retired and teach part-time. (5)

I am a graduate student and teach part-time. (2)

I am teaching part-time in the hope of eventually teaching full-time. (2)

I teach part-time at multiple institutions. (1)

I am not currently teaching part-time but have in the past. (1)

I am self-employed as an educational consultant. (1)

Most respondents also indicated teaching in higher education for more than 20 years showing a longevity possible in adjunct teaching we do not often hear about. Three respondents had taught between 10 and 20 years and an additional three had taught five to 10 years. Only one respondent indicated teaching one to five years and one respondent indicated being in their first year of teaching.

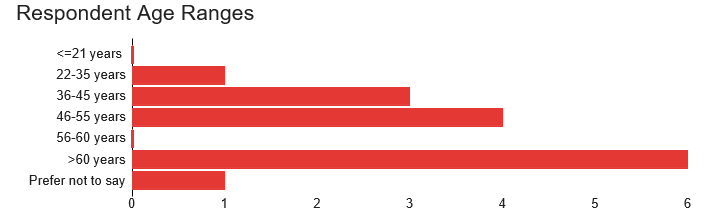

Survey respondent demographics. When asked about race, most respondents identified as White. One identified as Black and one preferred not to say. When asked about ethnicity, almost all identified as not Hispanic or Latino. One identified as having multiple ethnicities. And one respondent preferred not to say. Most respondents identified as female, with only four male-identified respondents. No one identified as non-binary or third gender. Respondent age ranged greatly with over 60 years of age being the most frequent response. The following graph shows the responses in each age range.

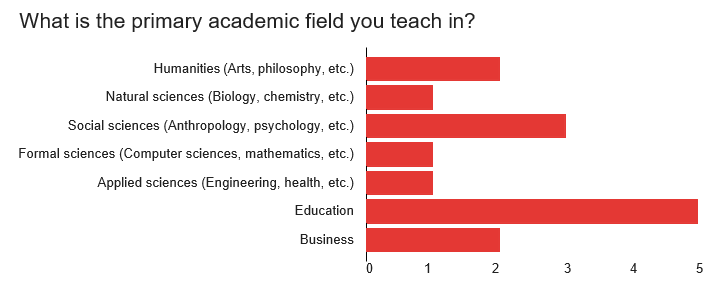

Survey respondent academic fields. Respondents to our survey were also from fields across the spectrum, with education being the most common. We acknowledge this may be due to some bias with those in education being more likely to respond. Social sciences, humanities and business were the next most common responses. And the natural, formal, and applied sciences had only one response each.

What led you to teaching?

In response to this question, most survey participants indicated a sense of joy and passion gained from passing their knowledge and experience forward. Below are just a few example responses.

I was led to teach because I enjoy connecting with students and supporting their learning. I teach various research topics in higher education for graduate students and also the freshmen success course for first-time students.

I am very passionate about sharing every bit of knowledge that I have acquired over the years with the younger generation and equally learn from them new ways of thinking and solving problems.

I’m a natural teacher & love being a professional, compassionate influence on future nurses. I was invited to teach at [my institution] as there was a shortage of clinical faculty and as an expert in practice, I couldn’t pass up the opportunity to help!

I was led to teaching by the experiences I had as a student and what struggles I witnessed other students being faced with.

Other respondents talked about the flexibility that teaching part-time allowed.

It is a great part-time job that allowed me to raise my children and work part time.

Teaching part-time has allowed me to have a platform to continue my professional goals.

I started teaching when my children were young, and I had left business. It ended up that I enjoyed teaching.

And some talked about teaching being built into other service obligations or contracts.

I received a graduate teaching assistantship in my MA program and learned to teach freshman composition. I realized I loved it, although I was not very good at it, and I changed careers from being a full-time writer to being a college faculty.

What is most fulfilling about your work, now or in the past?

We are often each fulfilled by different aspects of this work. And sometimes what most fulfills us changes over time. Many survey respondents talked about making a difference for students and helping them achieve their goals. Others spoke to the love of the work itself (e.g., lesson planning, goal setting, thinking of ways to make the content accessible). And finally, others found joy in the relationships they built with students and hearing feedback from students about their learning.

Being a role model for future nurses & sharing my truly vast knowledge of obstetrics and gynecology. When I pull in their pharmacology, anatomy & physiology to explain a topic, I love seeing the “light bulb” go off on their faces. It now seems to make sense to them. You can’t memorize all this; you have to understand it.

I appreciate the creative aspect of teaching and designing lesson plans that ensure effective learning in the classroom. Yesterday evening, I had a discussion with my students about creating learning objectives. I prepared a PowerPoint presentation with relevant examples and exercises and explained the steps involved in creating effective learning outcomes. It’s not an easy task, but I find it fulfilling. One of the things I enjoy the most about teaching is the opportunity to learn new things myself so that I can stay up-to-date and relevant in the classroom.

Describe areas or times you have received support, guidance, or camaraderie during your work.

We asked survey respondents what ways they have found to gain a sense of connection to their institution. Many talked about professional development opportunities and consultation services available through their centers for teaching and learning. If your institution does not have an annual professional development conference, check out this list of teaching and learning conferences maintained by the Elon University, Center for the Advancement of Teaching & Learning, many of which are free or at a small cost and welcome adjunct faculty as presenters.

Other respondents appreciated the opportunity to attend department faculty meetings commenting, “During lockdown, our department had online department meetings. It was a wonderful opportunity to connect with the other faculty members.” “The head of my department has reached out with various opportunities, to join the board, to attend meetings.” And finally, the library was often called out as a great resource and opportunity for networking. Consider looking for and taking advantage of such opportunities.

One respondent also shared their frustration with a lack of connection on their campus or support from their administration stating, “Not. Applicable. Period.” One interviewee did describe receiving support and attending regular departmental meetings, though it is uncertain of how common this is across campuses. Finally, many respondents touted the relationships they have built with staff in their centers for teaching and learning or academic technology support areas.

What are your hopes (beyond financial) for your work in the future?

While admittedly many of us teach to supplement or income, we wondered what other career goals adjunct faculty might have. Our last survey question asked participants to comment on their career goals. We may work to change our phrasing in future surveys, as one respondent noted an implied bias about low pay for adjunct work. The remaining responses generally fell into the following three categories.

- Life-long learning/staying current with research.

- Contributions to the profession/love of the work.

- Career changes, including hopes to teach full-time at some point, changing fields, and moving to an administrative position in higher education.

From these responses, we see there are many meaningful reasons we do this work, with many positive examples of adjunct faculty working to support students, to engage in creative activities, and to advance career goals, while finding joy in this calling.

How we Bolster our Passion for Teaching in Tough Times

First, we have learned that intentional efforts and attention to health and well-being needs to be a priority in this work, as many teach in more than one setting and regularly face challenges and stressors. For those of us who are teacher educators, it has been rewarding in recent years to learn of the growing global research focus on “teacher well-being” (Collett et al., 2019; Hascher & Waber, 2021; Olsen, S., & Collett, K., 2012): “Looking after the well-being of teachers …is critical for supporting their flourishing and retention” (Collett et al., 2019, p. 5). Employee health and wellness is extensively studied (Hascher & Waber, 2021), and we have found this to be an imperative focus in our efforts at staying positive while working as part-time faculty with diverse students studying to be educators during these rapidly changing and stressful times. This well-being lens fits well within our focus on the many positive aspects of this work, and once addressed and articulated, has led to our overall enjoyment of teaching.

Relationships play an important role in well-being and have an impact on overall learning outcomes (Hascher & Waber, 2021), and one reason we keep coming back to teaching. Included below are a few more examples of our current and/or past experiences of both challenging and also affirmative situations while working as adjunct faculty which highlight outcomes from developing positive relationships. Within Slapac et al.’s (2021) research during the pandemic, our colleague Sarah Coppersmith was impressed that graduate education teachers were able to navigate the many stressors and challenges in teaching by reaching out to find stability where they could, mainly relying on relationships with peers in their classes and also with faculty. This example opens the discussion of how faculty may adopt a Helping Relationship framework (Egan, 2002) which encourages student centered learning and lowering of stress.

Adopting a Student-Centered Teaching Approach

Continuing what we learned during the pandemic about extra efforts to support students (Slapac et al., 2021), and from the teacher well-being research (Collett et al., 2019), we follow various successful models of teaching that emphasize student-centered instruction. Our colleague Jill Johnson offers the Helping Relationship framework for a way to conceptualize professional interpersonal relationships that are for the purpose of one person assisting or teaching another (Egan, 2002).

Having positive professional interpersonal relationships is a critical ingredient in helping others effectively, particularly during these stressful times. In a helping relationship, the person being helped or taught may be identified in a role, like a client, patient, or student. This relationship becomes reciprocal in that the person being helped also becomes to their “helper” or teacher because they need help learning to master the course concepts and their study habits, to manage their lives, work and/or relationships more effectively. We have worked to identify and move to new perspectives regarding challenging situations and opportunities, helping with issues when needed that make a difference in our many diverse students’ lives (Egan, 2002), perhaps even paying more attention to these situations than educators did in prior decades.

When adopting a student-centered approach to teaching, we have found that much has to do with the personality of the person being assisted as well as the one who is assisting. Addressing this diversity, we can access the following factors important in helping relationships as described by Carl Rogers (1980): Empathy, Unconditional Positive Regard, and Genuineness, Realness, or Congruence, per Jill. We can practice these skills, though re-reviewing, discussing, and intentionally describing and using Rogers’ (1980) terms:

Empathy. Empathy is the ability to perceive accurately the feelings and personal meanings that someone else is experiencing and communicating this understanding back to them. This ability has a positive influence on the relationship and the outcomes that are needed.

Unconditional Positive Regard. It is important to convey or create an atmosphere of acceptance or caring. Whatever the person being helped is presenting in the communication—confusion, resentment, fear, anger, courage, love, or pride—there is an immediate feeling of being accepted by the helper as they are. This, too, has a positive impact on the success of the relationship.

Genuineness, Realness, or Congruence. The more the helper can be himself or herself in the relationship, not putting up a personal front or personal facade, the greater is the likelihood that the person being helped will change and grow in a constructive manner.

Within this frame, as a faculty you may find success by demonstrating a sense of commitment, efforts to understand, suspensions of critical judgment, showing of competence and caring, and including expressions of warmth, with positive results for the person being helped within face-to-face classes or online.

Additional examples from our experiences which exemplify student engagement and which have led to increasing satisfaction in teaching include: supporting students when ill, where appropriate, when needed, such as helping a few realize they should go to the health clinic, and when they return they have given the faculty credit for helping them. For example, one overworked and stressed student teacher was very ill all semester and was finally urged to go to the clinic. When they returned, they thanked the faculty for “saving their life” after the diagnosis and subsequent treatment. These stories are not easy to forget!

Additional instances include the idea of bringing snacks and water to class. We have been impressed when we notice other faculty bringing food for in-person evening classes to help get through a long day when classes end at 8 p.m. or later, though this is certainly not expected and often a challenge on an adjunct budget.

One time in an evening course a student became very stressed, and I learned that they had not eaten all day and did not have any money, so attempts were made to address the situation. – Sarah Coppersmith, Honors College

In addition, we have found that conversing with students when they need flexibility when ill, feel overloaded, or have too many credits in the semester goes a long way to help them find success. Another example practiced is when athletes enrolled in the class have upcoming games, asking them if it is okay to share the game time and location, and any media, with classmates, has been one way to develop community and support among classmates (Rogoff, 1994).

Other instances include when adjunct faculty can choose to help students before an assignment deadline by reviewing their work if asked, meeting electronically or in-person to tease out assignment details when needed, though not every faculty is able to do so for a variety of reasons (other work, timing, differing styles of teaching) as we learned through our interviews.

Thus, working from the well-being research (Collett et al., 2019) and the helping relationship angles (Egan, 2002), we have found the often-stressful adjunct teaching situations to be softened, rewarding, and very do-able as we work to help students succeed.

Resources, Tools and Quick Tips

While the chapters that follow will provide more detailed and nuanced resources by topic, we wanted to take this opportunity to share here a few practices and resources that help lessen stress and bring us joy. The following tips may be helpful for both online and in-person contexts for faculty from any discipline:

- Serving on two campuses, with research projects on another, the “Getting Things Done” method by David Allen (2015) was very helpful. It is an organization technique for capturing goals, notes, and plans weekly through a system which is popular worldwide, and while you can find the book online or in many libraries, there are also many free resources and videos. This resource can be especially helpful for faculty who work on more than one campus.

- For class, we enjoy incorporating faculty and student self-reflection: both practicing and modeling in class, shared online, or via oral dialog (Wells, 1999).

- Communications: Communicating on students’ written reflections, in the learning management system, in writing emails, through announcements, and via interactive communications have sometimes developed to even resemble blog dialog.

- Encouraging students to communicate back and forth on topics related to your discipline: Includes using peer reviews, where guidelines or well-written rubrics for feedback are provided. This was found to be helpful during the pandemic and going forward with student research projects (Slapac, et al., 2021).

- A helpful resource when students write research papers is to use the “They Say I Say” (Graff, 2018) writing prompts to help them avoid overused phrases.

- Offering mutually agreeable open, flexible office hours, versus only set times, for online and face-to-face classes has been helpful and has been a tool to help lessen student stress. It is often enjoyable to meet students, particularly from the online environment.

- Using updated rubrics with performance levels for your discipline helps students structure their assignments and provides a framework for fair grading (Arcuria & Chaaban, 2019).

- Being involved in conferences, grants, or projects with the community, there have been opportunities for students to also engage, related to the curriculum, giving career experiences which may fit on their resume for the future.

- These opportunities have given future educators the ability to develop skills in linguistically and culturally responsive practices within diverse settings such as developing a lesson for a local school, a conference presentation, poster, or work with neighborhood agencies. Related to this, there have been class visits from a local equal housing group with offers to engage students in fair housing efforts where possible.

- While teaching geography, one author designed field work and outdoor learning, such as sessions on mapping the campus or studying and mapping a German immigrant cemetery in a small historic village. Engaging with project-based-learning in the community has been rewarding for all.

- We enjoy listening to music when doing prep or rote work for relaxation or motivation, and like to use music when appropriate to encourage students, for example graduation tunes, relaxation music when needed, upbeat songs to motivate. For instance, one semester, one faculty played Vivaldi videos, when there was agreement in class, and at least one student asked to have it played again in subsequent classes. One must have a sixth sense on when music might help certain groups, and a query beforehand to see students’ interest is important, but do not be afraid to think about trying it (Willis, 2023). From experience, students may be interested in learning about early Elvis, Motown history and examples, orchestral tunes, Bee Gees, or playlists students enjoy which can be found online.

- When working with human service professions such as nursing, education, social work, health sciences, consider accessing the Overcoming Compassion Fatigue workbook (Teater & Ludgate, 2014) for graduate educators. This workbook includes many solid topics for reflection or discussion.

So, as you can see from this chapter there are many resources available to stay positive and productive as adjunct faculty. We have shared what has been important in our work, such as the details of a student-centered approach. From the tips here, you will be able to begin, or continue, positive professional and interpersonal relationships as you pursue this dynamic teaching journey.

Finding your People

As you acclimate to your campus you will likely collect a group of go-to folks for support. Below are a few recommendations we have for key folks to look out for and make friends with. Fill in the lines below to make a note of their name and contact information.

Department Chair or Course Steward: _____________________________________________________

There is likely someone in your department who knows your course well and has that broader understanding of how it fits into the students’ pathway through a degree program or general education track. This contact is a key person for discipline specific questions, copies of previous course material, and department policies.

Academic Technology Support: _____________________________________________________

You will learn quickly that having a go to person to help with the campus learning management system (LMS) and other important technologies will save you a ton of time and headaches.

Center for Teaching and Learning (CTL): _____________________________________________________

Most campuses have personnel dedicated to supporting faculty teaching efforts. These folks and the programs they run can be invaluable ways to connect to campus and find others who will help you find your value and validation. Ask about teaching circles or other programming specifically designed for adjunct faculty.

Your Campus Library: _____________________________________________________

Struggling to find time to search out the most recent literature on a topic? Or perhaps the academic journals you read for your discipline are a little advanced for your students. Your local librarian can save you a ton of time. They love looking for resource materials. Also many libraries now contract with services that provide educational videos licensed for student use. Do not be afraid to utilize these folks.

The Disability Access Services (DAS) Office: _____________________________________________________

You will likely have students in your class who require an accommodation of some type. While hearing, vision, and mobility accommodations are rare, many more invisible disabilities such as learning disabilities, ADHD, and dyslexia are very common. As a result, accommodations such as flexible deadlines and extended time on tests are common. When you receive an accommodation letter from your disability access services office, do not be afraid to ask them for suggestions on how to provide such accommodations.

Often in teaching we are so busy we do not take a moment to reflect on our own learning and growth. A great strategy many teachers use is a teaching journal to make notes about your experiences and ideas you have for future iterations of a class. We will end each chapter with reflection questions you might want to respond to in your teaching journal.

At what point in your teaching this semester did you feel most engaged with your students?

What brought you joy in teaching?

What goals would you like to set for yourself for your next semester?

Chapter 1 References

Allen, D. (2015). Getting things done: The art of stress-free productivity. Penguin Books.

Ambrose, S., Huston, T., & Norman, M. (2005). A qualitative method for assessing faculty satisfaction. Research in Higher Education, 46(7), 803-830.

Arcuria, P., & Chaaban, M. (2019, February 8). Best practices for designing effective rubrics. Arizona State University Design for Online Learning Toolkit. https://teachonline.asu.edu/2019/02/best-practices-for-designing-effective-rubrics/.

Brems, C., Baldwin, M. R., Davis, L., & Namyniuk, L. (1994). The imposter syndrome as related to teaching evaluations and advising relationships of university faculty members. The Journal of Higher Education, 65(2), 183-193.

Collett, K., Ngece, S., Mackier, E. & Rodgiers, S. (2019). Promoting holistic well-being of novice and student teachers: A handbook for school communities. Self-published, Cape Town. https://sites.google.com/view/teacherwellbeingdiversity/home.

Danaei, K.J. (2019). Literature review of adjunct faculty. Educational Research: Theory and Practice, 30(2), 17-33.

Egan, Gerard. (2002). The skilled helper: A problem-management and opportunity-development approach to Helping (7th ed.). Brooks/Cole.

Graff, G., Birkenstein, C., & Durst, R. K. (2018). They say I say: the moves that matter in academic writing with readings (Fourth edition). W.W. Norton & Company.

Hascher, T., & Waber, J. (2021). Teacher well-being: A systematic review of the research literature from the year 2000-2019. Educational Research Review, 34(8). https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1747938X21000348.

Huston, T. (2012). Teaching what you don’t know. Harvard University Press.

Ménard, D., Chittle, L., Bondy, M., Power, J., & Milidrag, L. (2023). ” I genuinely can’t understand why I was selected for the job”: Descriptions of the impostor phenomenon in university staff and professors. Transformative Dialogues: Teaching and Learning Journal, 16(1).

Olsen, S. T., & Collett, K. (2012, July). Teacher well-being: a successful approach in promoting quality education? A case study from South Africa. In Proceedings of the International Paris Conference on Humanities and Social Science Research-2012 (pp. 237-246).

Reybold, L. E. (2005). Surrendering the dream: Early career conflict and faculty dissatisfaction thresholds. Journal of Career Development, 32(2), 107-121.

Rogers, C. R. (1980). A way of being. Houghton Mifflin.

Media Attributions

- We follow various successful models of teaching that emphasize student-centered instruction

Part-time faculty at a college or university who typically work on a contractual basis. Similar terms include adjunct instructor, adjunct lecture, and part-time faculty. Adjunct faculty can be differentiated into different types.

Noted as a benefit, flexibility in the adjunct position includes pairing adjunct teaching at different institutions or with other types of full-time or part-time work.

An experience of perceived professional fraudulence or self-doubt, often in comparison to others.

An educators ability to be effective which can be impacted by both individual, institutional, and societal factors.

An approach to education that works to meet the unique, individual needs of students.

An academic area or vocational preparation defined by degree programs or preparation for a specific career pathway.

The process of providing feedback and a score on student work.

The strategies that an educator integrates students’ cultural frameworks in the learning environment.

Adjustments made to some aspect of learning (e.g., curriculum, environment, assignments, etc) that help students fully participate. Students with documented disabilities may have a legal right to accommodations.