Chapter 2: Academic Speak

Chapter Goal: To help make transparent much of the language used in academia that can create barriers for those new to teaching.

Scenario

Common Terms in Academia

It is easy to get lost in the complex maze that is higher education, sometimes also referred to as academia. In this chapter we define some common terms you will hear that will hopefully provide transparency and help you feel a little less of an outsider.

Course or Curriculum Sequencing

Here, course or curriculum sequencing is not the order of content within your course, but rather where your course falls within the other courses students take to complete a degree. For example, if you are asked to teach Accounting 101 you will be given a syllabus and student learning outcomes or skills. Does that tell you everything you need to know about what students need from this course? Likely not.

Other important information to know would be if the course fulfills a general education requirement, if there are courses students must take before this course also known as prerequisites, and if so, what you can assume students will come in already knowing. Further it is helpful to have an understanding of what subsequent classes students will take in which they will need to apply what they are learning with you. It might also be helpful to know if there is a professional licensure exam for which your course is instrumental in preparing students. Understanding the sequencing and bigger picture of the degree program(s) the course contributes to can help in assuring you know how to help your students be successful.

Credits or Units

College credits, sometimes referred to as units, measure the number of hours that are recognized for successful completion of a particular course of study (U.S. Department of Education website). This helps provide an equalized measure of time spent learning and studying for each college class. In a typical 15-week semester, a three-credit course, for example, usually meets close to three hours of class time per week. Many institutions will account for travel time so scheduled course time may be 2.5 to 2.75 hours. Sometimes that is in one class setting, for example evening classes tend to just meet once a week. Other times it might be split between two weekly class meetings, for example one hour and 15 minutes on Tuesdays and Thursdays. In addition, it is expected students will put twice that amount of time toward out of class work such as readings and homework assignments. So, a three-credit course might mean an expectation of six hours of student time outside of class each week.

A typical class is three credits, but this can vary greatly depending on the purpose of the course and if it includes additional extracurricular components. For example, classes with an added lab might add two additional credits, for a total of five credits. For further complication, some classes might be offered for varying credit hours. For example, some students might be enrolled for five credits and be expected to participate in a journal club or lab in addition to class time. Where other students might be enrolled for just three credits and not participating in these additional course activities.

An increasingly popular trend is to offer shorter duration classes. If a course is offered, for example as a three-credit hour 8-week course, the times above are doubled, requiring six hours of class time a week. Since the duration of the course is half but the student is still earning three credits they must meet twice as often and do twice the amount of out of class work. For other duration classes you can figure out the weekly class time by taking the total expected hours for a 15-week course (three credit hours x 15 weeks = 45 hours) and dividing it by the number of weeks the course is being offered.

Note some institutions refer to a 16-week semester, others a 15-week semester. Typically semesters are 16-weeks long but with a week-long Fall or Spring break. So the actual class time is over 15 weeks which is what you would typically use in your time calculation.

For asynchronous online classes, those being offered without any meeting times, figuring out how to calculate credit hours can confuse administrators, faculty, and students. Typically, online classes contain a statement in the syllabus something like the following:

If this course were offered on campus, you would be in class 2.5 hours/week plus travel time. The online version is no different in terms of expectations for your involvement. This is an active online course that requires 3 hours of your time each week in addition to the time it takes you to read the required materials, watch the videos, and complete the assignments. That means that you need to plan to spend a minimum of 6 hours every week (up to 9-10 hours a week) on activities related to this course.

Full-time undergraduate students typically take 15 credits a semester. At the graduate level, full-time is often defined with fewer credits as a higher level of effort is expected. Graduate students are also often working on thesis or dissertation research at the same time as coursework adding additional work not recognized by looking at their credit load alone.

Important questions to ask your department chair:

- What are the exact hours and days this class is expected to meet?

- How many credits is this course?

- Do some students take the course for a different number of credits? And if so, how do I know who those students are?

Discipline

The term discipline is used when we are talking about an academic area or vocational preparation defined by degree programs or preparation for a specific career pathway. In some cases this might be synonymous with a department or division name, for example History, Music, or Nursing. Others will use this more narrowly such as the discipline of museum studies within the field of history. If you are asked what your discipline is typically what someone is actually asking is what are you teaching.

Early Alert Systems

Most campuses have some sort of early alert system where you can raise concerns (aka flags) or praise (aka kudos) for students that will go to their academic advisors. Often the exact language you use also goes directly to the student so be careful in how you word your concerns. These systems have been shown to be powerful intervention strategies for students, especially freshman, falling through the cracks, to help them get connected to campus academic resources such as tutoring and advising, as well as non-academic supports such as counseling or the campus emergency services.

Enrollment Verification Surveys

Most colleges and universities also have some type of enrollment verification survey which must be completed early in the semester. This is tied to financial aid requirements ensuring students who are not coming to class to not get charged tuition. Be sure to complete this on time and indicate any student who has not come to class at all. They will be administratively dropped from your class by the registrar’s office.

When teaching online classes, determining attendance can be trickier. It is typically not sufficient for them to have just logged into the school’s Learning Management System (LMS). They should have completed at least one assignment or activity. As a result, it is often very helpful to have an introductory activity or get-to-know-you survey that students complete within the first week.

FERPA

The Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA) governs student data privacy among many other things. As an employee of your institution you have access to student records including their name, student ID, and grade details. As such you must adhere to the law concerning how this information is released and to whom. Most institutions will not let you access course roster details, the LMS, or other critical teaching systems until you have taken and passed their FERPA training in which you will learn the details of how to comply with this law. This ensures no delay in gaining access to the tools you need to be successful in teaching. Unfortunately, completing this training at one institution is rarely transferable to another. If you are teaching at multiple schools you will likely have to complete the training at each institution separately.

Important questions to ask your department chair:

- How do I complete the institution’s FERPA training?

- Is this training required annually or just once as part of the hiring process?

General Education

Some classes may not contribute specifically to a degree but may fill general education requirements for students. As a common part of all four-year degrees, these afford students the opportunity to develop and apply skills toward the breadth of knowledge necessary to succeed in a rapidly changing, technology-driven, and diverse world. These may include competencies such as managing information, communicating, and critical thinking. In some U.S. states, such as Missouri, a standardized core of general education classes is required, called the Core42. Other states may have similar standardization or leave it up to individual institutions or accrediting bodies to determine their general education requirements.

Learning Management System (LMS)

Today, most institutions have gone electronic adopting a Learning Management System, often just referred to as an LMS, to house course materials, communicate with students, collect assignments, and provide grades and feedback. There are many advantages to using an LMS. It certainly reduces the cost of copying materials when they can be easily posted online. It can also save time in keeping track of hard copies of materials that need to be hauled to and from class and risk getting lost. Communication through an LMS can streamline your process. We talk more about time saving strategies for using your institution’s LMS in chapter four.

Important questions to ask your department chair:

- Are any components of my course required to be in the LMS?

- Is there a previous copy of this course in the LMS that can I get access to?

Learning Outcomes or Objectives

Learning outcomes, sometimes also called objectives, describe what skills, knowledge or ability students should obtain after successful completion of your course, module or lesson. Often these are confused with what you plan to do and can read more like an agenda. But a truly well written outcome will define an observable and measurable action a student will perform which you can assess to determine if they have mastered that skill.

Bloom’s Taxonomy

While many different taxonomies exist to help define levels of learning, Bloom’s is by far the best known and most widely used. The revised version of Bloom’s defines six levels of learning (Anderson & Krathwohl, 2001). The table below provides a very brief definition of each level as well as a few verbs related to that level. You can find many more detailed resources online that provide greater depth.

|

Bloom’s Level |

Description |

Example Outcome Verbs |

|

Create |

Produce new or original work |

Design, assemble, construct |

|

Evaluate |

Justify a stand or decision |

Appraise, argue, defend |

|

Analyze |

Draw connections among ideas |

Differentiate, compare, distinguish, examine |

|

Apply |

Use information in new situations |

Implement, solve, demonstrate, operate |

|

Understand |

Explain ideas or concepts |

Describe, explain, select, translate |

|

Remember |

Recall facts and basic concepts |

Define, list, recognized |

As you write your outcomes consider these questions:

- What do you expect students to know as a result of completing this [course/module/lesson]?

- What do you expect students to be able to do as a result of completing this [course/module/lesson]?

- When do we want them to be able to do it?

Principles of Effective Learning Outcomes

- Directly related to the overarching goal of a program or course. It is helpful to write in specific knowledge and skills you expect students to acquire after completing the [course/module/lesson].

- The set of learning outcomes aims to capture the highest level of learning appropriate (See Bloom’s Taxonomy above)

- Each outcome should communicate a single outcome rather than combining multiple outcomes into a single statement.

- Each outcome should describe an observable behavior. For example, do not say a student should understand the principles of adult learning. Understand is vague and therefore hard to align with a course assessment. Instead, say a student should be able to describe the principles of adult learning.

Common Mistakes

- The outcome describes what will happen during a class or activity instead of the expected skill set a learner will have at the end. To avoid this make sure your outcomes always complete the sentence, “After completing X, the student will be able to…”

- The outcome is too vague or not measurable. Avoid using statements such as “the student will understand…” or “the student will know…” It becomes very hard to align these with a specific observable and measurable behavior. Always ask yourself, how would I know if the student accomplished this? What assessment would I use to determine we have achieved this outcome?

- The outcome level does not match the activity or assessment. For example, if the learning outcome is “After completing this simulation, participants will be able to evaluate the trauma level of a presenting child”, however the activity has them role playing but not conducting an evaluation. This is a misalignment of the outcome to the assessment. Use the Bloom’s Taxonomy or other available resources for taxonomy levels to assure you have alignment.

STEM or STEAM

In education you will frequently hear references to the STEM fields, or less frequently STEAM. This refers to a combination of the disciplines of Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEM). Sometimes the Arts are also added in to make the acronym STEAM. As these share similarities in both theory and practice they are often discussed collectively. These are typically high demand jobs and therefore often prioritized in K-12 an college-level curriculums.

Syllabus

The course syllabus is typically the guiding overview document to share with your students what they should expect from the course, critical information about who you are and how they can contact you, a course schedule overview, and information about how the course grade is determined. Some of the reference style syllabi can top 30 pages. Be sure your syllabus helps your teaching style show through. Also be aware that, as the first document most students see, it often sets the tone for the entire course and semester, and many campuses are now requiring standard wording depending on department policies.

Important questions to ask your department chair:

- Is there a syllabus template I am required to use or that is recommended for me to use?

- Is there a previous version of a syllabus for this course that I can see?

Textbook

Often the course textbook is selected and the bookstore is notified well in advance of the start of the semester for the book(s) required for the class. Efforts are also often made to standardize the textbook across all sections of a course or consider if a textbook can be used for multiple classes, for example can a student use the same text for Biology 101 and Biology 102. Be sure to clarify with your hiring department if this has already been selected or if you are able to be involved in the selection process for the course textbook.

Textbook tips:

- Sometimes textbooks can be confusing so check with your department chair or course steward to clarify the processes for ensuring students have early access, as well as understand any eBook options available.

- Double check that verbiage about the text(s) are clear in the syllabus before the semester begins.

- As a faculty you should be able to request a free copy from the department or publisher.

Open Educational Resources (OER)

Today it is also becoming more frequent for college classes to not have a textbook. With the wealth of information available online, faculty often find it easier to compile website links, videos, and other online resources to support students. Some even go as far as writing their own course materials and publishing them under a creative commons open access license. Using these free resources also has the added benefit of substantial cost savings for students. As a result, many institutions have major initiatives in place to encourage faculty to use OER in place of a textbook.

eBooks

Many publishers have battled the OER movement by providing electronic copies of their textbooks, often called eBooks, that contain additional interactive materials, assignments, videos and quizzes. EBooks also tend to be less expensive than a hard copy textbook thus providing some cost savings for students. And they tend to have other accessibility features such as working with screen readers. However, some students struggle to read for long periods on a screen. So if using an eBook check to see if there is an option for students to procure a printed version or print their own.

Important questions to ask your department chair:

- Has a textbook been selected already for the upcoming course section?

- Am I able to be involved in selecting the course textbook?

- Can the department provide me with a faculty, or desk, copy of the textbook?

- If using an eBook, who is the publisher contact for technical support?

- Are there initiatives or incentives in place for using OER in place of a textbook?

Choosing books for your class

There are times when adjunct duties include choosing course textbook(s). Consider the following points when making your selection.

- Price: Is the textbook affordable for students? When possible an option under $40 is desirable.

- Technology: Closely associated with price is the availability of an electronic version of the textbook. Check if an eBook is available and what features and options come with the book.

- No textbook option: It may be appropriate to use OER. Check with your department chair for options.

- Bookstore: Also check with the campus bookstore to make sure a textbook has not already been ordered for the course.

- Early decisions: Be aware of the possibility that the campus bookstore may reach out as early as the start of the previous semester to confirm and order the textbooks for your course.

Types of Adjunct Faculty

The number of adjunct faculty in higher education has been continually increasing. Numbers will vary from one region to another and between institution types.

According to the U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics’ Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System, as of Fall 2011, “adjunct faculty now represent 51.2 percent of instructional faculty among nonprofit institutions; tenured and tenure-track positions are 29.9 percent and full-time non-tenure-track are 19.1 percent” (2024, n.p.). “Characteristics of Postsecondary Faculty listed in fall 2022: of the 1.5 million faculty at degree-granting postsecondary institutions, 56 percent were full time and 44 percent were part time” (2024, n.p.).

The American Federation of Teachers’ Higher Education Data Center (2009) noted that the proportions of part-time and full-time faculty had nearly flipped; tenured and tenure-track faculty had declined to 33.5% and 66.5% of faculty were ineligible for tenure. Of the non-tenure track positions, 18.8% were full-time and 47.7% were part-time. Additional data tracking since this time find percentages of part-time faculty at most institutions consistent around 50%.

Many scholars have developed different typologies for adjunct faculty (Tuckman, 1978; Gappa & Leslie, 1993; Muncaster, 2011). The most complete version stems from Fuller, et al. ‘s (2018) work in which they provide the following differentiations and motivations for individuals to choose to work as adjunct faculty. First they break adjunct faculty into those who are voluntarily in this role and those who are involuntarily working as adjunct faculty.

Voluntary adjunct faculty would include the categories of: graduate students, outside specialists, voluntary freelancers, and career enders.

- If you are currently a graduate student you might be teaching as part of your financial aid package or to gain experience in the classroom. You could also be considered aspiring hopefuls if you anticipate full-time employment as a teacher after graduation.

- You would be considered an outside specialist if you are employed full-time outside of academia in addition to your adjunct teaching. Typically those in this category are not interested in full-time teaching at their current career stage.

- Voluntary freelancers are those who combine adjunct teaching with other part-time employment, or may just be teaching adjunct with no other employment.

- Career enders are those of you who have retired from your full-time career. You may have a love of teaching, a desire to remain current in your field, or are seeing adjunct teaching as a transition to full retirement.

Involuntary adjunct faculty including the categories of: aspiring hopefuls, and involuntary freelancers.

- You would be an aspiring hopeful if you are teaching adjunct with the hope it will lead to a full-time academic career.

- Involuntary freelancers “are traditionally understood as those who teach part-time and combine that with other part-time non-teaching positions” (Fuller et al., 2018, p. 19).

- Other scholars have labeled this category as road scholars and include also those who make a full-time career from multiple adjunct teaching jobs at multiple institutions (Gappa & Leslie, 1993).

You might or might not find yourself in one of these categories as there is no simple way to categorize the richness of experience and situation that brings teachers to an adjunct faculty position. You might also find you move between categories throughout your teaching career. But the hope in defining these categories is to demonstrate the diversity of ways in which faculty come to an institution.

Types of Institutions

Institutions of higher education can be classified in numerous ways. You might be most familiar with athletic classifications such as Division I, II or III. This refers to the National College Athletic Association’s structure for organizing athletic programs. Within each division there are separate conferences, or groupings of teams, that compete against each other such as the Atlantic Coast Conference, the Big Ten, and the Ivy League (NCAA website).

However, within academia, we most often think of the Carnegie Classifications. These classifications provide a framework for understanding the primary focus of an institution. They were started in 1970 by the Carnegie Commission on Higher Education and today they include: doctoral universities, master’s colleges and universities, baccalaureate colleges, baccalaureate/associate colleges, associate colleges, special focus colleges, and tribal colleges (ACE website). An institution would be classified by the highest level degree awarded. For instance, a 4-year university issuing bachelor’s, master’s, and doctoral degrees would be classified as a doctoral university.

Within these classifications, subdivisions are often arranged, for example, doctoral universities are typically divided based on the level of research in which they engage. An R1 classification, for example, would be used for a doctoral granting university rated as very high research activity.

Other types of classifications include Land-Grant Institutions and Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs). Land-Grant institutions were established by the Morrill Act in 1862 which awarded expropriated tribal lands for these institutions to be built (National Archives website).This was later expanded by the Second Morrill Act of 1890 to include institutions for people of color. Today there are 106 land-grant colleges and universities in the U.S. (USDA website). Title II of The Higher Education Act of 1965 officially established HBCUs which it defined as “any historically black college or university that was established prior to 1964, whose principal mission was, and is, the education of black Americans” (U.S. Department of Education website, p.1). In 2021, there were 99 HBCUs in the U.S. (NCES Fast Facts website).

Typical Institutional Structures

Each institution has its own culture and structure. In this section we have provided some of the most common language you will hear at four-year institutions in the United States. For example a four year university will likely have several colleges (College of Arts and Science, College of Nursing, etc.), broken into multiple departments (Department of History, Department of Music, etc.). Alternatively, a two-year community college is likely to be broken into schools (School of Business, School of Nursing, etc.) and each school will be broken into multiple divisions (Division of Accounting, Division of Marketing, etc.).

President versus Chancellor

The head of the university is most commonly called the president. In some university systems where there are more than one affiliated university or campus, each campus may have a chancellor who reports to the overall system president (Wikipedia: Chancellor (education)).

Provost versus Dean

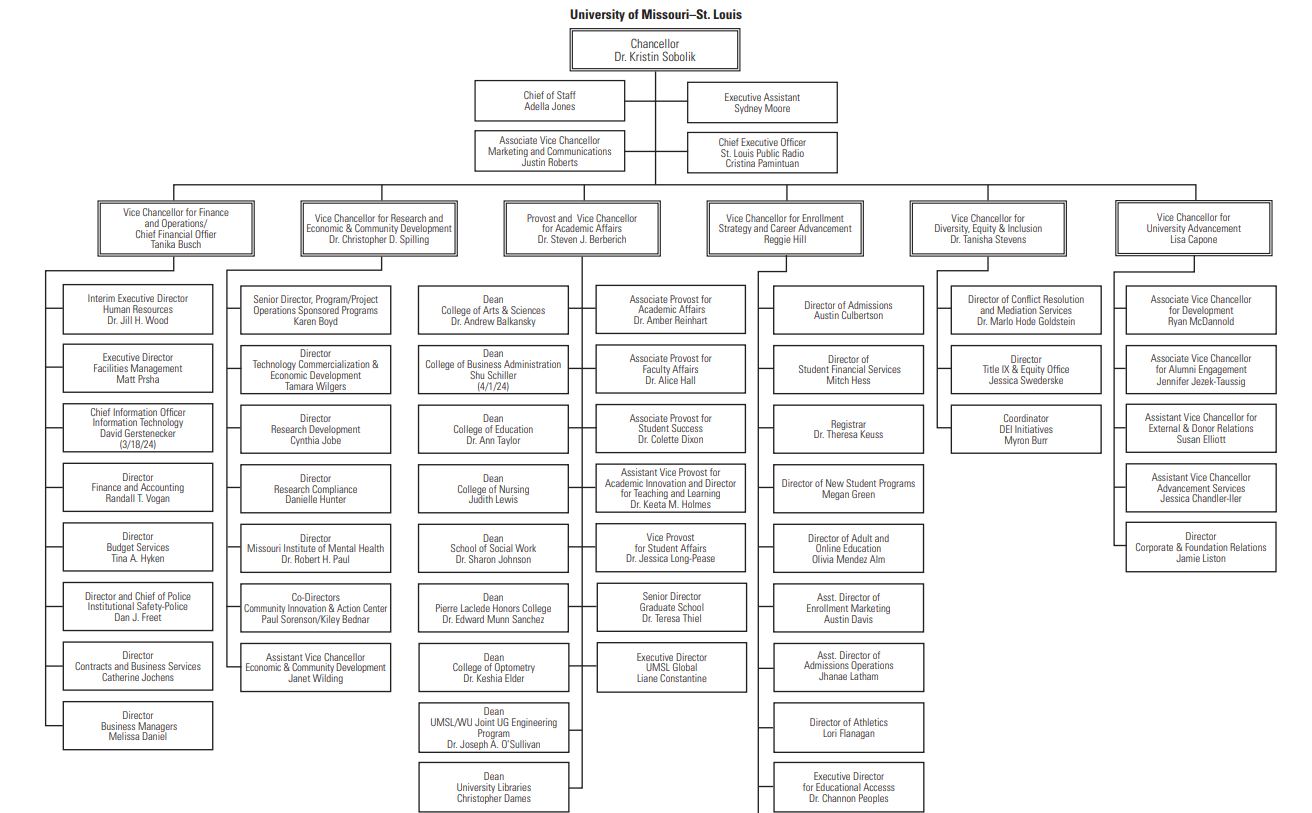

Deans and provosts provide oversight for universities assuring they deliver a quality educational experience. Deans work at the departmental level, while a provost oversees the broader educational offering. “A dean’s main responsibility is to ensure that departments meet their academic goals. A provost’s main responsibility is to oversee the overall development of all the educational programs a college or university offers” (Maryville University blog). In some institutions, such as in the example below, deans report to the provost.

The example university organizational chart below comes from the University of Missouri-St. Louis, which is part of a state system of universities referred to as the University of Missouri-System.

Department Chair

Each college within a university is typically divided into multiple departments (sometimes called divisions). The department chair is typically a member of the faculty appointed by the dean, who holds the position for a limited period of time.

For smaller colleges there might only be one department, thus the college and department are synonymous and therefore a separate department chair is not identified. In these cases the dean serves as the department chair.

Course Steward

Some departments opt to further break down educational leadership by identifying a course steward to oversee the consistency and delivery of a course. You may be directed to the department chair or full-time faculty responsible for oversight of your course(s). This helps provide consistency across multiple faculty teaching a course, and ensures learning outcomes are kept for the overall curriculum. For example your course might provide needed skills that are not provided in any other classes in a degree program.

Consider asking your course steward or department chair how your course contributes to the degree program/s to prepare students for their career path. This can help you assure the material and assignments you provide meet those broader degree goals.

Chapter 2 Reflection Moment

Often in teaching we are so busy we do not take a moment to reflect on our own learning and growth. A great strategy many teachers use is a teaching journal to make notes about your experiences and ideas you have for future iterations of a class. We will end each chapter with reflection questions you might want to respond to in your teaching journal.

What new terminology did you learn this semester that was helpful to your understanding of your teaching journey?

What new connections did you make at your institution that helped mentor or support you in your teaching?

What would you like to learn more about next semester?

Chapter 2 References

American Federation of Teachers. (2009). The American academic: The state of higher education workforce 1997-2007. Washington, D.C. American Federation of Teachers. http://www.aftface.org/storage/face/documents/ameracad_report_97-07for_web.pdf.

American Council on Education (ACE) website. https://carnegieclassifications.acenet.edu/.

Anderson, L. W., & Krathwohl, D. R. (Eds.) (2001). A taxonomy for learning, teaching, and assessing: A revision of bloom’s taxonomy of educational objectives (Complete ed.). New York, NY: Addison Wesley Longman.

Fuller, R., Kendall Brown, M., & Smith, K. (2017). Adjunct Faculty Voices: Cultivating Professional Development and Community at the Front Lines of Higher Education.

Gappa, J.M., & Leslie, D.W., (1993). The invisible faculty: Improving the status of part-timers in higher education. Jossey-Bass.

Maryville University Blog. Provost vs. Dean: Differentiating Two Key Higher Education Roles. https://online.maryville.edu/blog/provost-vs-dean/.

Muncaster, K. (2011). Supporting adjunct faculty within the academy: From road scholars to retired sages, one size does not fit all (Doctoral dissertation). http://hdl.handle.net/2345/2426.

National Archives website. https://www.archives.gov/milestone-documents/morrill-act.

National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) website. https://www.ncaa.org/sports/2021/2/16/overview.aspx.

National Center for Education Statistics. (2024). Characteristics of Postsecondary Faculty. Condition of Education. U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences. https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator/csc.

National Center for Educational Statistics (NCES) Fast Facts. https://nces.ed.gov/fastfacts/display.asp?id=667.

Tuckman, H. P. (1978). Who Is Part-Time in Academe? AAUP Bulletin, 64(4), 305–315. https://doi.org/10.2307/40225146.

U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) website. https://www.nifa.usda.gov/about-nifa/how-we-work/partnerships/land-grant-colleges-universities.

U.S. Department of Education website on Credit Hours. https://www2.ed.gov/policy/highered/reg/hearulemaking/2009/credit.html.

U.S. Department of Education website on HBCUs. https://sites.ed.gov/whhbcu/one-hundred-and-five-historically-black-colleges-and-universities/.

Wikipedia: Chancellor (education). https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chancellor_(education)#:~:text=A%20chancellor%20is%20a%20leader,resident%20head%20of%20the%20university.

Media Attributions

- Chapter 2 Infographic 2

A measure of the typical time spent learning and studying to successfully complete a course. These are sometimes called units.

A system focused on proactively communicating about students who may be struggling to promote support and success.

A confirmation of a student's enrollment status at a school. Enrollment verification may be needed for student-specific benefits such as financial aid. Faculty members may be asked to complete a survey which identifies whether students are attending the courses in which they are enrolled.

A method (often electronic software) that supports the delivery (administration, planning, tracking, reporting, etc.) of an educational or training program.

A book in electronic form rather than a printed, hardcopy. The term eText may also be used.

A, typically free, copy of the textbook provided by publishers to an educator to support to academic activities such as teaching.

A framework used to categorize colleges and universities in the United States which was developed by the Carnegie Commission on Higher Education in 1970.

A college or university which is designated to receive benefits of the Morrill Acts by a state legislature or the U.S. Congress.

Colleges and universities originally founded to educate Black, or African American, students.

Formal and informal ways colleges and universities are organized which may include roles, rules, values, and policies.

A leader at a college or university. When there are multiple campuses, chancellors may head a single campus and report to a president.

A person who heads a department within a college or university with a focus on meeting academic goals.

A senior leader at a college or university who focuses on overseeing the overall development of educational offerings.

A faculty member who is appointed to represent and support the administrative management of their department.

A person who knows a course well and how it fits within a larger degree program. This person may teach the course or support the consistent delivery of the course.