Chapter 5: Giving Feedback

Chapter Goal: To provide practical tips and strategies which helpful guidance and feedback without becoming overwhelmed or overloaded.

Why do we grade? Oh grading! It is often the bane of faculty existence. So much time and effort and, “do students ever even look at my feedback”? Well we would alternatively argue that grading can be some of the most important work we do when it comes to supporting student learning.

As faculty it is our responsibility to provide feedback that informs the student’s perception of their work in relation to the objective or standard of their task. Your personalized feedback also helps students know you have looked at the work they have prepared. Not receiving feedback can make a student feel unvalued or unheard. Feedback is also as much about relationship building as it is student growth.

The student’s role is to utilize the feedback to reflect on their learning and utilize it to improve on future tasks. However, feedback which does not take student differences and motivation into account may miss the mark (Bolton, 2022; McKanry, 2023). This student-driven reconceptualization of feedback should include notions of feedback as informal, non-traditional, and relational as opposed to transactional or one-way, (Matthews, et al., 2024). See our section below on sustainable feedback practices to consider ways to customize feedback to the student without it becoming overwhelming.

Formative versus Summative Feedback

Scenario

When done well, grading can be the moment students start to understand what they do and do not know, and where comprehension errors are corrected. As an educator I have found that the best way to help students be successful in my course is to ascertain students’ prior knowledge in relationship to the course. A one-time test is not necessarily the indicator. This can however be determined through class discussions and/or writing on reading prompts. I have provided reading prompts for students to read and respond to in class, having them give their understanding of the topic.

Through class discussions on assigned topics related to the course, I have found that responses to discussion and/or writing prompts can identify the level of understanding and comprehension of the subject matter. Many times, students will respond based on their understanding, which can also be an indication of students’ academic, culturally related, or personal experiences. In this context, this allows a faculty to look at the uniqueness that each student brings. This helps me be intentional in my educational approach, drawing from my students their prior knowledge and using it as a guide to build a deeper more significant curriculum. – Ida Casey, University of Missouri-St. Louis, Education Sciences and Professional Programs

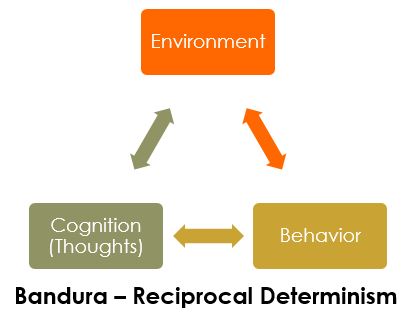

When we think about feedback we usually think in terms of points and grades. But that is limiting by nature. Consider instead that learning is an iterative process of practice, feedback, and revision. Bandura (1978; McKanry, 2019), one of the archetypes of understanding how learning works, identified three key components to learning: Cognition (the thoughts in our head), the environment (feedback), and behavior (a student’s performance on an assessment).

These work collaboratively together to construct or form knowledge. Thus formative feedback is anything that helps support the student’s learning. When you provide formative feedback you are providing a critical element of that knowledge building process. Summative feedback is more of a final determination of what the student learned. Below are some characteristics and examples of formative versus summative feedback.

|

|

Formative Feedback |

Summative Feedback |

|

Characteristics |

Helps guide learning Used to inform future instruction/gauge student understanding/progress May or may not be officially graded May have a self-assessment or reflective component |

Measures learning Collected at the end of a learning activity

|

|

Examples |

Feedback on essay drafts In-class discussion Clicker questions Weekly quizzes |

Mid-term exam Final exam, project or presentation End-of-course portfolio |

Note that some feedback can be both. For example a mid-term exam may be worth a good part of the grade and therefore be considered high-stakes and summative. But students can also get a sense from this where they are understanding material well and where they need to focus more attention.

Scenario

You can also build in activity to further enhance the formative nature of an assessment. One good example is an exam debrief, sometimes called an exam-wrapper, where students have the opportunity to understand and reflect on what they did wrong as well as have the correct information or solution strategy reinforced.

Students’ emotional response to feedback also affects the effectiveness of that feedback and if it leads to learning development, or is detrimental to their motivation (Middelton, et al., 2023). To this end it is important to develop our skill to carefully craft supportive feedback that motivates learners to continue to grow.

Using Growth Mindset Language

Dweck (2008) found students may approach feedback with one of two types of mindset, fixed or growth. With a fixed mindset you believe skills are inherent traits and cannot be changed. Students with a growth mindset see struggle or failure as a learning opportunity and have been found to try harder since they believe effort can result in improvement. You can promote a growth mindset in your students by using encouraging language in your feedback. Dweck often refers to this as the “not yet” strategy in which instead of telling a student they are wrong, you tell them they are not there yet, implying they will be at a future point.

Growth mindset example language (adapted from Education.com 2019):

Acknowledge effort:

- This was a difficult task, but your hard work paid off!

- Wow. You have been working so diligently on your math skills. I can see the impact it has had on your work.

Encourage learning:

- Is there another strategy you can try?

- Let’s learn how to do this.

Focus on the behavior not the individual:

- I do not see… (instead of You didn’t…)

Recognize mistakes:

- Mistakes can help us learn what to do better next time.

- I struggled with this too in my college classes.

Praise creativity:

- That was a creative way to solve your problem!

Celebrate success:

- It was really hard to get started on this, but look where you are now!

Emphasize improvement:

- If you learn and practice, you will be able to do it on your own.

- You can improve your skills with effort and practice.

Encourage feedback:

- Who can you ask for feedback/advice?

- …is what I am hearing. Is that what you meant to say?

Formatting Feedback

Scenario

Bolton (2022) defines five key characteristics of quality grading.

- Accurate—very important decisions are made by and about students on the basis of grades; if these are going to be good decisions, the grades need to be accurate.

- Consistent—grades should not be a matter of chance based on what class section students are in. If they are achieving at the same level, they should get the same grade, but frequently this does not happen because faculty have different ideas about the ingredients of grades and performance standards.

- Meaningful—grades should be based on and give information about achievement of standards/learning goals; if they do not, they are just symbols.

- Supportive of learning—traditional grading practices (i.e., putting a number on everything that students do) have led students to think that school is about the accumulation of points. Constructive, supportive honesty sustains the student’s motivation while offering an honest picture of the path ahead.

- Timely—feedback should follow the performance as closely as possible to be impactful. The farther the gap between when students complete a task and when they get feedback the less they learn from that feedback.

Consider the following strategies to provide feedback that meets these criteria for quality.

Feedback sandwich

An option you will hear mentioned frequently when searching for feedback strategies is the feedback sandwich. In this format you start and end with a strength and put the bad news in the middle.

Example 1-Writing: Julie, I really liked the overall flow of your narrative. Your second paragraph was a bit confusing and seemed to lose focus in the middle. But your end was strong and drove home your key thesis point.

Example 2-Math: Kamara, you are using the correct formula here. Great job, there were several to select from so that alone is a great step here in the right direction. However, I think your calculations in step 2 were incorrect resulting in your answer being off by ten. I think if you go back and review that step you will find the rest of your calculation was correct.

This strategy of softening your critical feedback can be effective. But for some students they may miss the key message if it is buried between areas of strength. If you find students seem to be missing your suggestions for improvement, consider a clearer strategy such as two thumbs up and a wish.

Two thumbs up and a wish

This strategy is similar to the feedback sandwich but provides more structure and consistency for your students by giving transparency about what they should expect.

Example 1-Writing:

-

- Thumbs up: You have amazing, outside the box ideas. I always look forward to reading your submissions because you make me laugh and smile.

- Thumbs up: There is clear improvement here in your writing style over your last assignment. I can see you have taken advantage of the template I handed out in class. Your thesis statement is clear and presented early in the document and you support it well with the points you make throughout.

- Wish: I would like to see you focusing more on your grammar. Consider using a grammar checking tool in Word or Google Doc or something external like Grammarly to help you identify areas for improvement. I look forward to seeing your improved grammar on your next assignment.

Example 2-Programming:

-

- Thumbs up: I was able to successfully run your code and you have met all the criteria for this assignment.

- Thumbs up: Your graphics are improving. The colorful car was a very creative touch.

- Wish: Looking at your code you have not included any comments. Comments are important to help you when you return later to your code or for other programmers building on what you have written. I would like to see you expanding the use of comments in your future assignments.

Focus on three things

Many faculty struggle to find the right amount of feedback to give. Do you spend hours drafting detailed and personalized feedback? Or do you keep it short risking students believing you do not care, and also losing an opportunity to help the student grow? A good general rule is to focus on three recommendations for improvement relative to the student’s level. This is your zone for learning, sometimes called the Zone of Proximal Development (Vygotsky, 1978; Raslan, 2024).

|

Too little feedback |

Zone of Learning |

Too much feedback |

|

No learning |

|

Student is overwhelmed |

Instead of focusing your feedback on where you would like students to get to by the end of the course, focus on the next step of learning.

Example 1-Chemistry:

Sam, You are doing well and I know you know this material so I do not want you to get too discouraged by this grade. I have three suggestions for you that I think will help improve your work next time.

-

- I would like to see you focusing on the accuracy of your calculations. You are almost there but often just being one decimal off will result in an incorrect answer. I think if you slow down a bit and double check your calculations at each step you will be in good shape.

- It looks like you are struggling with the solution dilution. Chapter 3 in our book has a great diagram on page 120 that I recommend you review. I think that might help you visualize better what you are trying to accomplish.

- Remember, practice makes perfect! Keep working with dilutions, and you will master the concept. We have an open lab on Thursdays if you would like to stop by and practice.

Video or audio alternatives

Text feedback can be difficult when you need to deliver a critical message. Consider accompanying or replacing the feedback with a video or or giving audio comments. Video feedback can also be an effective way to build relationships with students in online or particularly large classes. And lastly depending on your technical skill or style, you might find videos a faster option. Most LMS systems today have these tools built in or at least have the ability to upload video.

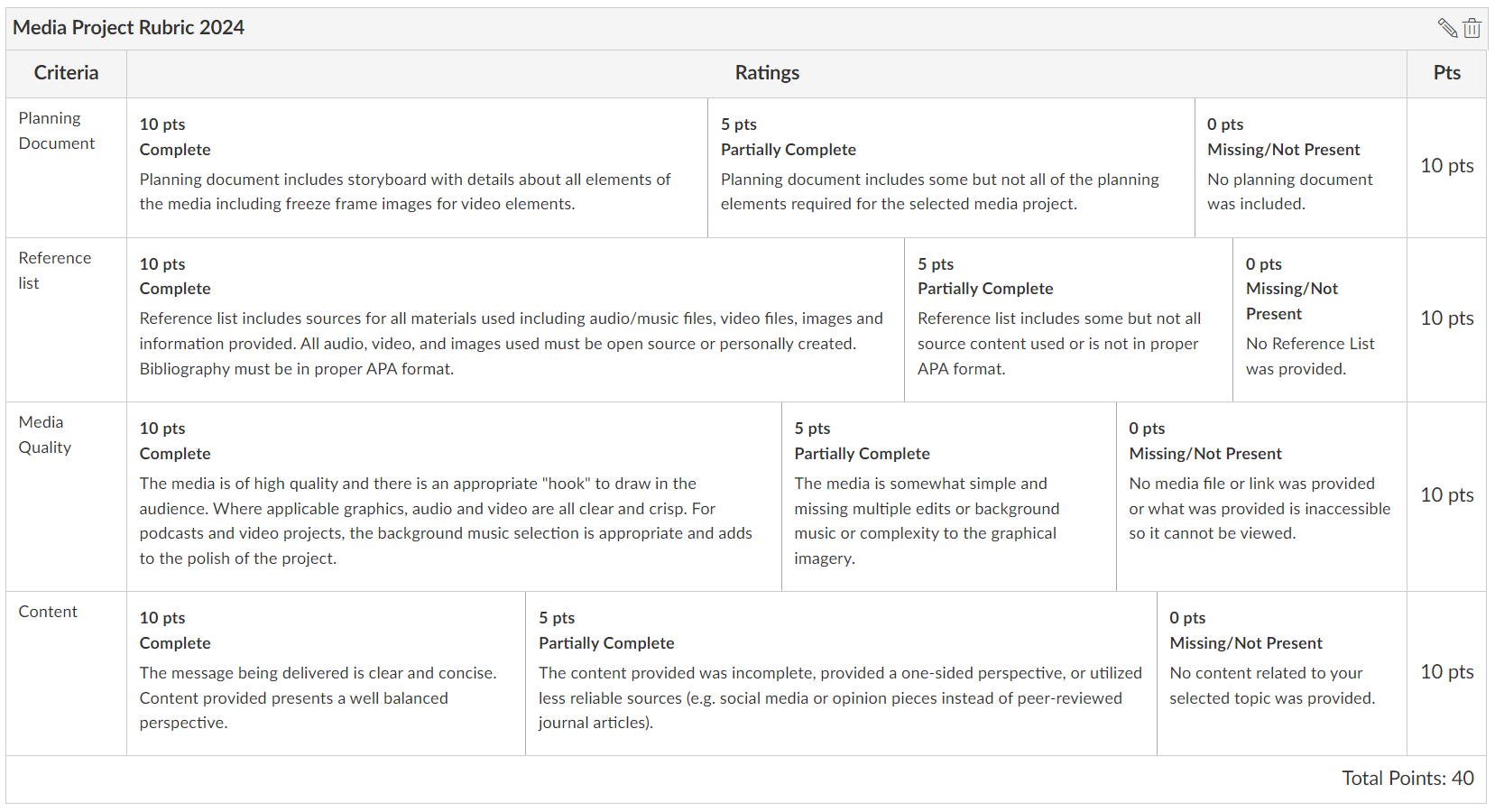

Rubrics

Rubrics can be a great way to give feedback efficiently, often with just a click, as well as provide transparency about your expectations for quality work and how you value each component of an assignment. A typical rubric provides criteria for the assignment and what performance would look like at different levels.

Rubrics can be divided into three types, analytic, single-point, and holistic (Gonzalez, 2014). Consider your feedback goal in selecting the type that works best for you. You will find lots of rubric libraries available online. Our motto is never recreate from scratch when you can Google or use generative AI to create.

Analytic rubrics

The most common type of rubric you will encounter is an analytic rubric which breaks down an assignment into criteria and defines levels of success or ratings for criteria. This type of rubric often allows very quick grading, especially when built into your LMS. It also gives students a clear picture of why they received their score. However it can sometimes feel a little over prescribed and limiting and they can be time consuming to create.

Holistic rubrics

A holistic rubric does not break out individual criteria for an assignment. Rather it just provides descriptions of an assignment at different performance levels. See how the media project rubric example from above looks different as a holistic rubric.

|

Score |

Description |

|

40 |

Assignment is complete with a clear storyboard and media description, reference list in proper APA format, high quality media, and a clear and concisely delivered message. |

|

30 |

Assignment is almost complete but missing one of the required elements. |

|

20 |

Assignment is poorly visualized, multiple elements are missing or of poor quality. Main message you were trying to deliver was not clear. |

|

10 |

Assignment was substantially incomplete and/or of poor quality media. Main message you were trying to deliver was not clear. |

Single-point rubrics

With a single-point rubric you define your criteria as you would in an analytic rubric, but you only define the criteria for meeting proficiency for the assignment. You then leave open text areas for notes where a student might have been either below or above your expectations. The example below would be a single-point rubric for our same media project.

|

Evidence of exceeding standards |

Criteria Standards for this performance |

Areas that need work |

|

|

Planning Document: Planning document includes storyboard with details about all elements of the media including freeze frame images for video elements. |

|

|

|

Reference List: Reference list includes sources for all materials used including audio/music files, video files, images and information provided. All audio, video, and images used must be open source or personally created. Bibliography must be in proper APA format. |

|

|

|

Media Quality: The media is of high quality and there is an appropriate “hook” to draw in the audience. Where applicable graphics, audio and video are all clear and crisp. For podcasts and video projects, the background music selection is appropriate and adds to the polish of the project. |

|

|

|

Content: The message being delivered is clear and concise. Content provided presents a well balanced perspective. |

|

Feedback for Writing

Evaluating writing can be some of the most time consuming of your grading work. Due to its subjective nature, there is often not a clear right or wrong. Further, it is often an iterative process requiring many drafts. Below is an example feedback strategy from an online criminology class.

Scenario

Sustainable Feedback Practices

Scenario

If we honor the learning process in our feedback and grading practices we can make our class a learning game rather than a grading game. Managing our time and processes can help us do this by allowing us to focus our efforts on the teaching and not the logistics.

Consider volume and how this will impact time management. Be kind to yourself and intentional about creating a process that you can sustain without burning out over time. Below are several tips from our writing team’s years of experience.

- Color code or use other visual cues to keep your course materials separate. This is easier when using an LMS. But consider color-coded binder clips or sticky notes when teaching two courses, especially if they are two of the same session.

- Say no to reinventing the wheel. Nothing has to be made from scratch. Many libraries of rubrics or example feedback language can be found online. Even consider using a generative AI tool* (e.g., ChatGPT, Gemini, CoPilot) to suggest example feedback or rubric text.

- Schedule your grading time so you can do it in manageable batches. Grading 100 essays at a time is a soul sucking endeavor. Choose to grade a certain number per day and communicate to students when you expect to have feedback back to the whole class. LMS systems and other grading software typically allow you to hold scores as you grade in order to release all at one time.

- Strategize what to grade first. Consider looking at samples from a stronger student, an average student, and a struggling student when grading products, projects, or essays. This can give you a sense of common errors and help you determine early which skills to address to the whole class and which to address individually or in small groups.

- Take note of common errors. Re-teach these instead of commenting on every product.

- Use rubrics and saved comments. Consider a process that allows you to store and reuse common comments. For example create a document where you store these libraries of comments. Some LMS tools also let you save previous comments for reuse.

*Note consult your campus academic technology staff on recommended generative artificial intelligence (AI) tools supported on your campus. Never feed student work into an AI tool that has not been vetted by your campus for FERPA compliance as this essentially gives your students’ intellectual property to the AI company.

Student Perspective

The quotes below were provided by student leaders participating as student-faculty partners in a 2023 summer course design workshop at the University of Missouri-St. Louis.

What motivates you to read/engage with feedback?

- Sometimes I may be confused about an assignment so I just do my best and I do well, but I still need some feedback because I was confused and maybe just lucky I got what the professor was looking for – especially in writing assignments.

- I want to know why points were given or not given.

- I appreciate feedback not only on my individual performance, but also about what the class struggled with or did well with. This helps assure me how I am doing, kind of a benchmark against my peers.

What timing it best for feedback?

- I appreciate opportunities for feedback before submitting assignments, such as in built in reflections, check ins, early drafts. After completing the assignment I’ve kind of moved on to the next thing in the course.

- Soon after. If I wait too long I won’t care anymore or I wont remember everything as well. Most of the time I think a week or two is good.

- Enough but not too much time after. 🙂 Especially after a test, I need enough time to calm down, but soon enough after that I can prepare properly for the next test. Maybe in the next class.

What is not as helpful or disengaging feedback?

- I appreciate feedback both about what I did well and what I could improve on. The corrective feedback can be a learning experience.

- Especially for problem based classes, I wouldn’t mind corrective feedback as it helps you improve for the next exam.

- I’m sensitive but also oblivious. so I need to be told clearly but nicely :’)

- Be specific about what was wrong and how it could be improved.

Do you prefer written, video, or audio feedback?

- Depends on the assignment. On a written assignment audio/video is better so they can really explain it. But for a standardized exam or M/C, written is fine.

- I think that the visual feedback is helpful to really create a positive prof-student relationship and might encourage the student to reach out if they’re experiencing difficulty compared to written feedback.

Often in teaching we are so busy we do not take a moment to reflect on our own learning and growth. A great strategy many teachers use is a teaching journal to make notes about your experiences and ideas you have for future iterations of a class. We will end each chapter with reflection questions you might want to respond to in your teaching journal.

What feedback strategy were you most satisfied with this semester and why?

What new feedback resources or tools did you discover this semester?

What would you like to try or tweak next semester on your continuous improvement journey?

Chapter 5 References

Bandura, A. (1978). The self system in reciprocal determinism. American Psychologist, 33, 344-358.

Barkley, C. & Major, C. (2022). The engaged teaching handbook: A guide for college faculty. Social Good Fund, The K. Patricia Cross Academy.

Bolton, N. (2022, October). Grading student learning. Presentation for Center for Teaching and Learning, Certificate in University Teaching program. Saint Louis, MO.

Dweck, C. S. (2008). Mindset: The new psychology of success. Ballantine Books.

Education.com (2019, August 27). Language to use to foster growth mindset. https://blog.education.com/2019/08/27/language-to-use-to-foster-growth-mindset/

Gonzalez, J. (2014, May 1). Know your terms: Holistic, analytic, and single-point rubrics. Cult of Pedagogy. https://www.cultofpedagogy.com/holistic-analytic-single-point-rubrics/

Matthews, K. E., Sherwood, C., Enright, E., & Cook-Sather, A. (2024). What do students and teachers talk about when they talk together about feedback and assessment? Expanding notions of feedback literacy through pedagogical partnership. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 49(1), 26-38. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2023.2170977

McKanry, J. (2023, September). Giving and promoting feedback. Presentation for Center for Teaching and Learning, Certificate in University Teaching program. Saint Louis, MO.

McKanry, J. (2019). Building community in online faculty development. [Dissertations, University of Missouri-St. Louis]. 906. https://irl.umsl.edu/dissertation/906

Middleton, T., ahmed Shafi, A., Millican, R., & Templeton, S. (2023). Developing effective assessment feedback: Academic buoyancy and the relational dimensions of feedback. Teaching in Higher Education, 28(1), 118-135. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2020.1777397

Raslan, G. (2024). The impact of the zone of proximal development concept (scaffolding) on the students problem solving skills and learning outcomes. In: Al Marri, K., Mir, F.A., David, S.A., Al-Emran, M. (Eds.). BUiD Doctoral Research Conference 2023. Lecture Notes in Civil Engineering, vol 473. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-56121-4_6

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes (M. Cole, V. John-Steiner, S. Scribner & E. Souberman., Eds.) (A. R. Luria, M. Lopez-Morillas & M. Cole [with J. V. Wertsch], Trans.) Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. (Original manuscripts [ca. 1930-1934])

Information and guidance given to improve learning.

Evaluation typically given at the end of learning (e.g., a unit, topic, course) that provides feedback to students about their performance.

A type of assessment that has a high impact on a student (e.g., grading, course completion). This is in contrast to lower-stakes assessments. For example, a final examination worth a significant portion of the final grade would be higher-stakes in comparison to a short, ungraded quiz.