Chapter 7: Thriving Under Pressure: Workplace Stress and Emotional Dynamics

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, you should be able to do the following:

- Describe the stress cycle and explain how physiological, psychological, and behavioral responses to stress unfold over time.

- Identify common workplace stressors, including organizational, interpersonal, and environmental sources—and recognize how they differ across roles and cultures.

- Analyze the short- and long-term outcomes of stress, including impacts on health, performance, attitudes, and organizational effectiveness.

- Evaluate strategies for managing stress within organizational contexts, including wellness programs, supportive communication, role clarity, and workload design.

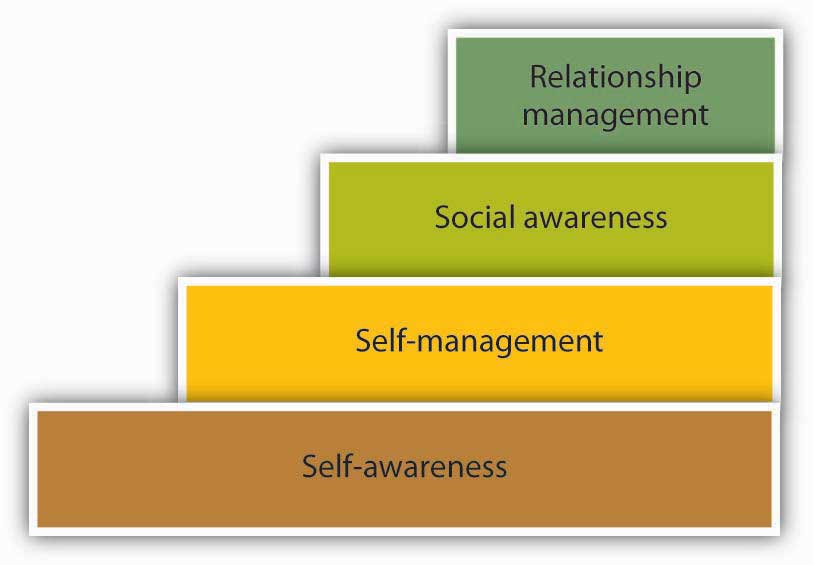

- Explain the influence of emotions on workplace attitudes, decision-making, teamwork, and leadership communication.

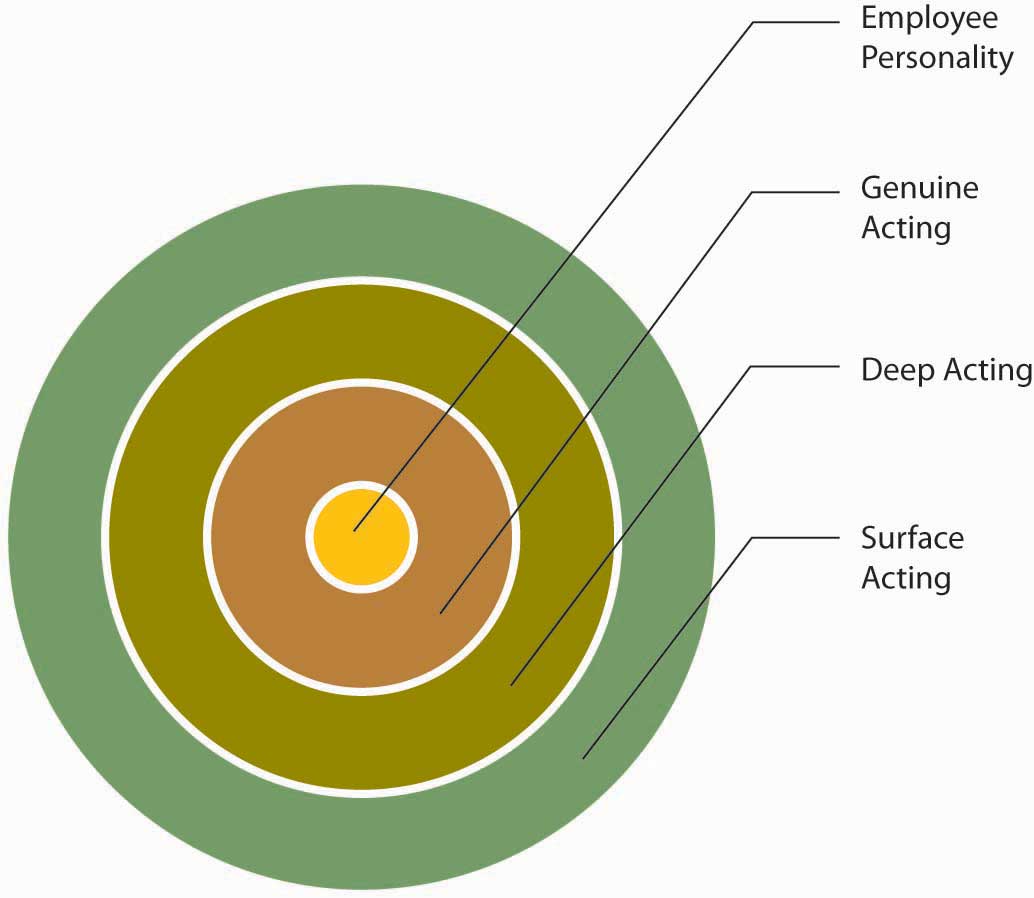

- Define emotional labor and explore techniques to manage it effectively in service-oriented and high-interaction roles.

- Assess how emotions shape ethical perceptions and behaviors, and how emotional awareness can support ethical decision-making.

- Compare cross-cultural differences in stress experiences, coping strategies, and emotional norms across global workplaces.

Section 7.1: Spotlight

Organizational Stress and Emotional Mismanagement in the St. Louis Metropolitan Police Department

The St. Louis Metropolitan Police Department (SLMPD) faced a prolonged period of organizational stress following the 2014 Ferguson unrest, which exposed deep fractures in both community trust and internal operations. Officers were thrust into high-stakes, emotionally charged environments with limited institutional support. According to the Ethical Society of Police (2020), many officers reported burnout, emotional exhaustion, and a lack of psychological resources. This aligns with the stress cycle model, where prolonged exposure to stressors—without adequate coping mechanisms—leads to physical, emotional, and behavioral strain (Robbins & Judge, 2022).

Key sources of stress included public scrutiny, racial tensions, inconsistent leadership communication, and internal inequities in promotions and discipline. Officers of color, in particular, faced dual pressures: navigating community expectations while contending with systemic bias within the department (Taylor, 2017). These stressors produced outcomes such as increased turnover, absenteeism, and a breakdown in morale. The absence of structured emotional support systems—such as peer counseling or debriefing protocols—exacerbated the situation, leaving officers to internalize trauma without relief.

Emotions and attitudes played a central role in shaping workplace dynamics. Officers reported feeling undervalued, mistrusted, and emotionally isolated. These negative affective states contributed to a culture of cynicism and defensiveness, which in turn impaired decision-making and interpersonal communication. Emotional labor—the requirement to suppress personal feelings in order to display organizationally appropriate emotions—was especially taxing in this context. Officers were expected to remain composed and authoritative in volatile situations, often without the emotional tools or institutional backing to do so (Hochschild, 1983).

The ethical implications of unmanaged emotional stress were significant. Officers under chronic stress were more likely to engage in reactive or ethically questionable behavior, particularly in high-pressure encounters. The lack of emotional regulation and support contributed to incidents of excessive force and biased policing, as documented in the Center for Policing Equity’s (2021) analysis of SLMPD’s use-of-force data. Emotional exhaustion blurred the line between ethical judgment and survival instinct, undermining the department’s stated values of integrity and fairness.

Cross-cultural stressors further complicated the organizational climate. Black officers reported facing discrimination in hiring, promotions, and disciplinary actions, which created a sense of alienation and mistrust within the ranks (Ethical Society of Police, 2020). These officers often bore the emotional burden of representing the department to communities of color while simultaneously experiencing marginalization internally. The lack of cultural competence in leadership communication and policy enforcement deepened these divides, making it difficult to foster a unified, resilient workforce.

In conclusion, the SLMPD case illustrates how unmanaged stress, emotional labor, and cultural insensitivity can erode organizational ethics and performance. Addressing these issues requires more than policy reform—it demands a shift in organizational communication, emotional intelligence, and leadership accountability. Without these changes, the cycle of stress and dysfunction is likely to persist, undermining both officer well-being and public trust.

References

Center for Policing Equity. (2021). Findings from the National Justice Database: St. Louis Metropolitan Police Department. https://www.stlouis-mo.gov/government/departments/mayor/news/justice-database-study-report-released.cfm

Ethical Society of Police. (2020). Report on the St. Louis Metropolitan Police Department. https://esopstl.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Report-on-the-St-Louis-City-Police-Depart-0001-1.pdf

Hochschild, A. R. (1983). The managed heart: Commercialization of human feeling. University of California Press.

Robbins, S. P., & Judge, T. A. (2022). Organizational behavior (19th ed.). Pearson.

Taylor, H. (2017). Being Black, While Wearing Blue: Comprehensive Evaluation of the St. Louis Metropolitan Police Department. Ethical Society of St. Louis. https://www.ethicalstl.org/being-black-while-wearing-blue-comprehensive-evaluation-of-the-st-louis-metropolitan-police-department-an-ethical-society-of-st-louis-podcast-by-heather-taylor-president-of-the-ethical/

Discussion Questions

- How does the stress cycle manifest in high-pressure workplaces, and what are the long-term outcomes for both individuals and organizations when stress is not effectively managed? Can you think of examples where unmanaged stress led to a breakdown in performance or morale?

- What are some common sources of stress in organizations, and how do these stressors differ across roles or cultural contexts? How might these stressors lead to outcomes such as burnout, absenteeism, or ethical lapses?

- How do emotions and attitudes influence workplace behavior and decision-making, particularly in high-stress environments? In what ways can negative emotions, such as frustration or fear, impact perceptions of fairness or ethical behavior?

- How does emotional labor—such as suppressing personal feelings to display organizationally appropriate emotions—affect employees’ well-being and ethical decision-making? Can you think of situations where emotional labor might lead to ethical dilemmas or conflicts?

- How do cross-cultural differences in stressors and coping mechanisms complicate workplace dynamics? What strategies can organizations use to address these differences and create a more inclusive and supportive environment for all employees?

Section 7.2: What Is Stress?

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, you should be able to do the following:

- Explain the General Adaptation Syndrome (GAS) and its application to organizational stress, including how the alarm, resistance, and exhaustion phases manifest in workplace settings.

- Identify and classify major workplace stressors, such as role demands, digital communication overload, work–family conflict, cultural misalignment, and ambiguous communication norms.

- Analyze the multidimensional impact of stress, including psychological, physiological, and performance-related outcomes, with attention to emotional regulation and organizational dynamics.

- Explore individual differences in stress response, including personality traits, cultural background, gender, and communication style—and their influence on coping strategies and workplace behavior.

Stress—a term borrowed from the physical sciences—originally described the force exerted on an object. In human terms, it refers to the external and internal pressures that challenge our ability to adapt. Psychiatrist Peter Panzarino (2008) described stress as “forces from the outside world affecting the individual,” a definition that still resonates in today’s fast-paced, hyperconnected work environments.

Psychologists define stress as the body’s response to any demand that requires physical, mental, or emotional adjustment (Dyer, 2006). But in organizational contexts, stress is more than a biological reaction—it’s a communicative experience shaped by how individuals interpret, express, and manage pressure within social systems (Kaiser, 2018; Lee, 2025).

Stress can be energizing—the push that gets us out of bed, fuels ambition, and drives performance. But when unmanaged or miscommunicated, it becomes destructive, leading to burnout, disengagement, and ethical lapses (Sapolsky, 2017; Sutton, 2025).

Recent data underscores the urgency:

- Over 80% of American workers report feeling workplace stress at least some of the time (Pew Research Center, 2023).

- 63% of workers say stress has led them to quit jobs, citing sleep disruption and negative thought patterns (American Psychological Association, 2022).

- In the UK, nearly 400,000 new cases of work-related stress, anxiety, and depression were reported in 2021–2022, resulting in 17 million lost workdays (Clarke, 2022).

Organizational communication scholars argue that stress is not just a reaction—it’s a relational signal. It reflects how employees experience role clarity, feedback, psychological safety, and emotional labor in their daily interactions (Deetz, 1992; Jablin, 1987). When stress is openly acknowledged and constructively addressed, it becomes a resource for growth rather than a liability.

This chapter explores how stress unfolds in organizational life, how emotions shape behavior and ethics, and how communication can be used to recognize, regulate, and reframe stress for healthier outcomes.

Understanding the Stress Cycle: From Triggers to Coping

Stress is not just a biological reflex—it’s a communicative and relational experience shaped by how individuals interpret, express, and manage pressure within organizational contexts (Kaiser, 2018; Lee, 2025). While the physiological roots of stress are well-established, modern research emphasizes the role of emotional regulation, organizational messaging, and psychological safety in shaping how stress unfolds and is resolved.

The Brain’s Response to Stress

Our autonomic nervous system governs unconscious functions like breathing, digestion, and heartbeat. When a threat is perceived—whether physical danger or a looming deadline—the amygdala, part of the limbic system, triggers the fight-or-flight response (Cannon, 1915). This reaction floods the body with adrenaline and cortisol, increasing heart rate, sharpening focus, and suppressing non-essential functions like digestion.

Importantly, the amygdala doesn’t differentiate between physical threats and social or psychological stressors. A tense meeting or performance review can activate the same biological response as escaping danger, which is why workplace stress can feel so visceral.

General Adaptation Syndrome (GAS)

Hans Selye’s General Adaptation Syndrome (GAS) remains a foundational model for understanding how stress progresses through three stages (Selye, 1956; Selye, 1976):

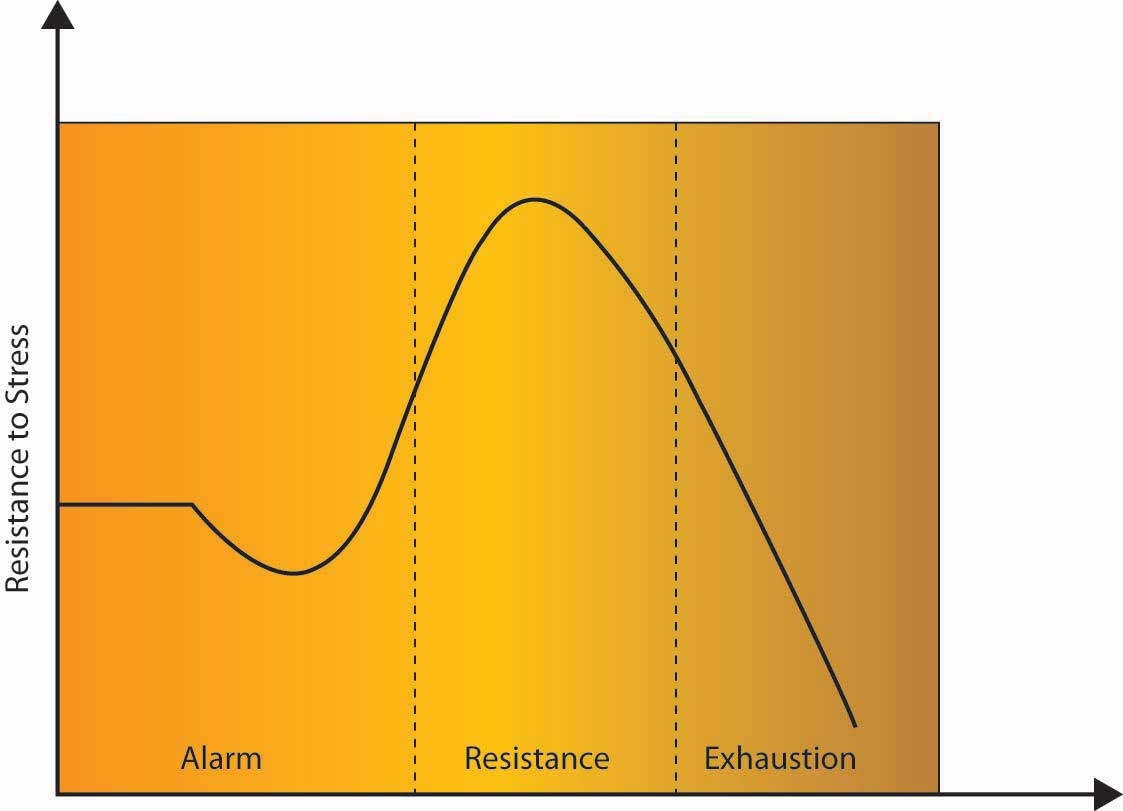

Figure 7.2

In Selye’s GAS model, stress affects an individual in three steps: alarm, resistance, and exhaustion.

In the alarm phase of stress, an outside stressor jolts the individual, insisting that something must be done. It may help to think of this as the fight-or-flight moment in the individual’s experience. If the response is sufficient, the body will return to its resting state after having successfully dealt with the source of stress.

In the resistance phase, the body begins to release cortisol and draws on reserves of fats and sugars to find a way to adjust to the demands of stress. This reaction works well for short periods of time, but it is only a temporary fix. Individuals forced to endure the stress of cold and hunger may find a way to adjust to lower temperatures and less food. While it is possible for the body to “adapt” to such stresses, the situation cannot continue. The body is drawing on its reserves, like a hospital using backup generators after a power failure. It can continue to function by shutting down unnecessary items like large overhead lights, elevators, televisions, and most computers, but it cannot proceed in that state forever.

In the exhaustion phase, the body has depleted its stores of sugars and fats, and the prolonged release of cortisol has caused the stressor to significantly weaken the individual. Disease results from the body’s weakened state, leading to death in the most extreme cases. This eventual depletion is why we’re more likely to reach for foods rich in fat or sugar, caffeine, or other quick fixes that give us energy when we are stressed. Selye referred to stress that led to disease as distress and stress that was enjoyable or healing as eustress.

Stress as a Communicative Experience

Organizational communication scholars argue that stress is shaped by how it’s talked about, managed, and supported in the workplace. Stress becomes more manageable when:

- Employees receive clear feedback and role clarity

- Leaders foster psychological safety and open dialogue

- Teams engage in collaborative problem-solving rather than isolation

When stress is ignored or stigmatized, it escalates. But when it’s acknowledged and addressed through supportive communication, it can become a catalyst for growth and resilience (Deetz, 1992; Jablin, 1987; Sutton, 2025).

Ten Sources of Stress in Organizational Life

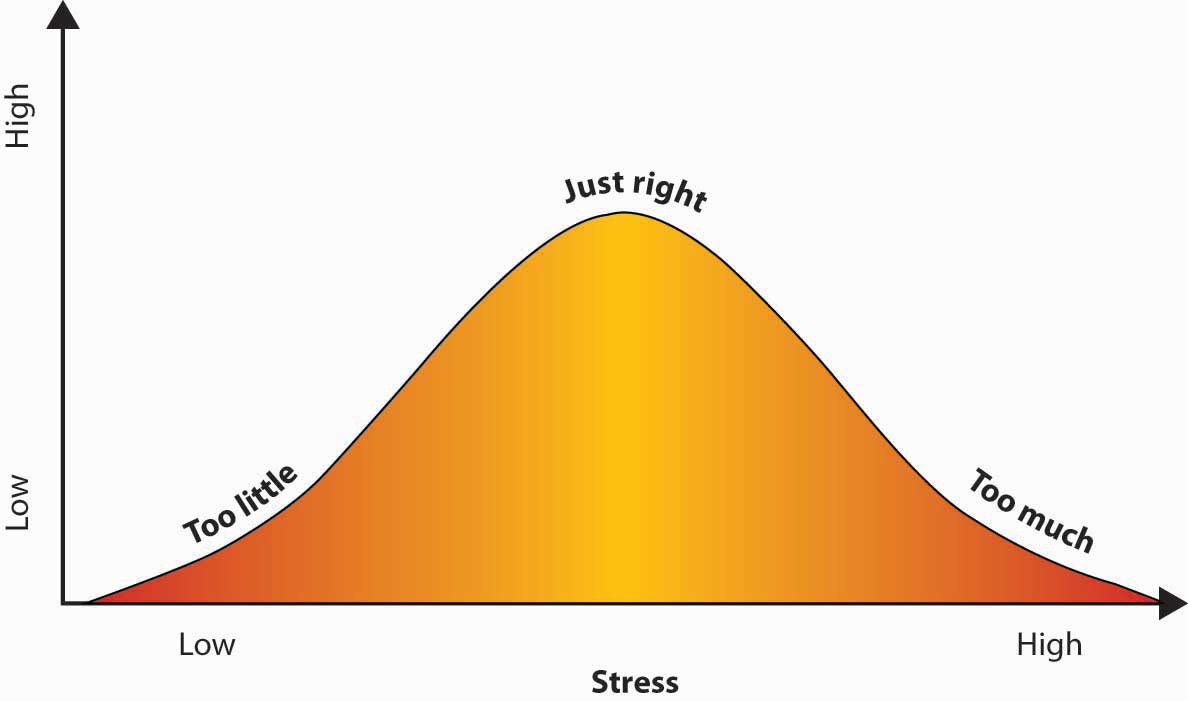

Stressors are events, interactions, or environmental conditions that trigger a physiological or psychological stress response. While stressors are often viewed negatively, they are not inherently harmful. In fact, moderate stress can enhance focus, motivation, and performance—what psychologists call eustress (Selye, 1976). However, when stressors accumulate without adequate recovery or support, they can lead to distress, burnout, and disengagement.

Organizational communication scholars emphasize that stress is shaped not only by external pressures but also by how those pressures are interpreted, discussed, and managed within the workplace (Kaiser, 2018; Sutton, 2025). For example, unclear expectations, poor feedback loops, and lack of psychological safety can amplify the impact of otherwise manageable stressors.

Recent data highlights the widespread nature of workplace stress:

- The American Psychological Association (2022) reports that top stressors for U.S. adults include money, work, family responsibilities, and housing—all of which are deeply intertwined with employment and organizational life.

- Workplace dynamics, such as team conflict, lack of autonomy, and poor communication, are increasingly cited as root causes of chronic stress (Lee, 2025; Psychology Today, 2025).

Stress is cumulative. A single stressor may be manageable, but repeated exposure to multiple stressors—especially without adequate support—can lead to emotional exhaustion, cognitive overload, and relational strain. This is why understanding the sources of stress in organizational contexts is essential for designing healthier, more resilient work environments.

One major category of workplace stressors is role demands—the expectations, responsibilities, and pressures associated with a specific job or position. But stress also arises from information overload, work–family conflict, life transitions, and organizational change. Each of these will be explored in the sections that follow.

1. Role Demands

Role demands refer to the expectations, responsibilities, and pressures associated with a person’s position in an organization. When these demands are unclear, contradictory, or excessive, they become powerful stressors that can undermine performance, motivation, and well-being (Quick et al., 1997; Eatough et al., 2011).

Organizational communication scholars emphasize that role stress is not just about workload—it’s about how roles are defined, communicated, and supported. Employees thrive when they understand what’s expected of them, feel empowered to meet those expectations, and receive consistent feedback. When these elements are missing, stress escalates.

Types of Role Stress

| Type of Role Stress | Description | Common Outcomes |

|---|---|---|

| Role Ambiguity | Unclear expectations, vague responsibilities, or lack of feedback | Emotional exhaustion, low job satisfaction, turnover intentions |

| Role Conflict | Contradictory demands from different stakeholders or tasks | Frustration, ethical strain, reduced performance |

| Role Overload | Too many responsibilities or insufficient time/resources | Burnout, absenteeism, decreased creativity |

Role Ambiguity

Role ambiguity occurs when employees are unsure about what their responsibilities are, how success is measured, or what behaviors are expected. This is especially common during onboarding, organizational change, or in poorly structured teams. High role ambiguity is linked to:

- Lower job satisfaction and performance

- Higher emotional exhaustion and turnover intentions

- Difficulty adjusting to new roles or cultures (Bauer et al., 2007; Gilboa et al., 2008; AJHSSR, 2020)

Role Conflict

Role conflict arises when employees face incompatible demands—such as being asked to cut costs while improving customer satisfaction. It can also occur when personal values clash with organizational expectations (e.g., being asked to promote a product one doesn’t believe in). Role conflict is associated with:

- Increased stress and burnout

- Reduced organizational commitment

- Lower team cohesion and trust (Beamible, 2025; Lee et al., 2019; Schmidt et al., 2014)

Role Overload

Role overload happens when employees are expected to do more than they can reasonably handle, either in terms of time or complexity. This often occurs after downsizing, during rapid growth, or in understaffed teams. Role overload contributes to:

- Physical and psychological strain

- Declines in performance and innovation

- Higher absenteeism and turnover (Tang & Vandenberghe, 2021; Widmer, 1993; Eatough et al., 2011)

Interestingly, some employees may respond to overload by increasing their effort—especially if they view it as a challenge rather than a threat (Frontiers in Psychology, 2021). However, sustained overload without support leads to resource depletion and long-term harm.

2. Information Overload: Navigating the Digital Deluge

Information overload occurs when the volume, frequency, or complexity of incoming messages exceeds an individual’s ability to process them effectively. In today’s hyperconnected workplace, employees are bombarded by emails, chats, notifications, reports, and meetings—often across multiple platforms. This constant stream of input can lead to cognitive fatigue, decision paralysis, and emotional exhaustion (Bawden & Robinson, 2020; LumApps, 2025). Originally defined by Schick, Gordon, & Haka (1990) as a mismatch between information demands and processing capacity, information overload now includes:

- Digital communication overload: Excessive emails, Slack messages, and app notifications

- Technostress: Stress caused by the use of digital tools and platforms (Marsh et al., 2024)

- FoMO (Fear of Missing Out): Anxiety from not keeping up with updates or conversations (Barry, 2024)

A 2022 OpenText survey found that 80% of workers reported information overload as a source of daily stress, with frequent interruptions and email addiction contributing to burnout (YAROOMS, 2022).

Organizational communication scholars emphasize that information overload is not just a technical issue—it’s a relational and structural challenge. It reflects how communication is designed, filtered, and prioritized within the workplace (Deetz, 1992; Jablin, 1987). Poorly managed communication systems can:

- Undermine employee engagement and trust

- Reduce decision-making quality

- Fragment team cohesion and collaboration

When employees are overwhelmed, they may disengage, ignore messages, or avoid communication altogether—leading to information avoidance and communication breakdowns (Speakap, 2025; LumApps, 2025).

Strategies for Managing Overload

To reduce information overload, organizations can:

- Streamline communication channels and eliminate redundancy (YAROOMS, 2022)

- Promote asynchronous communication and “right to disconnect” policies (Woxday, 2025)

- Use AI filters and automation to prioritize relevant messages (Barry, 2024)

- Encourage digital detox windows and focus time blocks (Together Platform, 2023)

- Train employees in information literacy and boundary-setting

Effective internal communication is not about sending more—it’s about sending better.

Top 10 Most Stressful Jobs in 2025

- Lawyer High burnout rates due to tight deadlines, ethical dilemmas, and adversarial environments.

- Surgeon Life-or-death decisions, long hours, and intense pressure in operating rooms.

- Paramedic/EMT Emergency response under unpredictable and traumatic conditions.

- Firefighter Physical danger, irregular hours, and exposure to traumatic events.

- Compliance Officer High stakes in managing legal and ethical risks across industries.

- Mental Health Counselor Emotional labor, secondary trauma, and high caseloads.

- Construction Worker Physically demanding work, safety risks, and tight deadlines.

- Registered Nurse Long shifts, emotional strain, and responsibility for patient outcomes.

- Delivery Truck Driver Time pressure, isolation, and physical fatigue.

- Medical Records Technician High responsibility for data accuracy and confidentiality under tight timelines.

References

Adam, J. (2025, February 21). 15 most stressful jobs for 2025. U.S. News & World Report. https://money.usnews.com/careers/articles/the-most-stressful-jobs

MastersDegree.net.. (2024, January 23). Top 10 most stressful jobs in the world (2025). https://mastersdegree.net/most-stressful-jobs-in-the-world/

MyCVCreator. (2025, March 28). 10 most stressful jobs: Careers with the highest demands. https://www.mycvcreator.com/blog/10-most-stressful-jobs-careers-with-the-highest-demands

3. Work–Family Conflict: Navigating the Spillover Between Roles

Work–family conflict is a form of interrole tension that arises when the demands of work and family are mutually incompatible, such that participation in one domain makes it difficult to fulfill responsibilities in the other (Greenhaus & Beutell, 1985; Netemeyer, Boles, & McMurrian, 1996). This conflict can flow in two directions:

- Work interfering with family (WIF): e.g., long hours or emotional strain from work affecting home life

- Family interfering with work (FIW): e.g., caregiving responsibilities disrupting work schedules

In today’s digital-first workplace, this conflict has intensified. The rise of remote work, constant connectivity, and dual-earner households have blurred boundaries between professional and personal life (APA, 2023; LumApps, 2025). A recent ADPI Research Institute survey found that average weekly work hours in North America more than doubled from 4 to 8.9 hours of overtime between 2020 and 2021 (Richardson & Klein, 2021), contributing to a spillover effect that heightens stress across domains. Stress in one domain often amplifies stress in another. For example:

- A demanding job may reduce time and energy for family responsibilities

- Family stressors (e.g., illness, childcare) may impair focus and productivity at work

This cumulative stress can lead to:

- Lower job and life satisfaction

- Burnout and emotional exhaustion

- Reduced organizational commitment and performance (Allen et al., 2000; Ford, Heinen, & Langkamer, 2007; Frone et al., 1992; Hammer et al., 2003)

Interestingly, research shows that women experience slightly higher levels of work–family conflict than men, likely due to persistent gender norms around caregiving and emotional labor (Kossek & Ozeki, 1998; Shockley et al., 2017).

Organizational Strategies for Work–Life Balance

Organizations that support work–life balance are perceived as more attractive and ethical employers (Barnett & Hall, 2001; Greenhaus & Powell, 2006). Effective strategies include:

- Flexible scheduling and remote work options

- Supervisor support for family and personal life (Kelly et al., 2014)

- Family-supportive organizational cultures, including childcare resources and paid leave policies (Allen et al., 2013)

Communication scholars emphasize that supportive messaging, empathetic leadership, and clear boundaries are essential for reducing work–family conflict and promoting employee well-being (Deetz, 1992; Jablin, 1987).

4. Life Changes and Downsizing: Navigating Stressful Transitions

Major life changes—whether joyful or painful—can significantly disrupt an individual’s emotional, cognitive, and behavioral equilibrium. Events such as marriage, relocation, caregiving, or job loss often require rapid adaptation, and when multiple transitions occur in close succession, the cumulative stress can lead to burnout, emotional exhaustion, and health deterioration (APA, 2024; Workplace Strategies for Mental Health, 2024).

The Holmes-Rahe Life Stress Inventory remains a foundational tool for assessing the impact of life events. For example:

- Death of a spouse: 100 (highest stress)

- Marriage: 50

- Job loss: 47 (Fontana, 1989)

These scores reflect the relative strain each event places on the body and mind. Importantly, stressors are cumulative—meaning that multiple life changes in a short period can compound vulnerability to illness and psychological strain (Inc., 2018).

Among life changes, downsizing is one of the most disruptive in organizational contexts. It affects not only those who lose their jobs but also those who remain—often referred to as “survivors”—who may experience guilt, anxiety, and increased workload (APA, 2025; Lipman, 2024).

Recent studies show:

- Downsizing leads to elevated stress, anxiety, and low self-esteem, especially when layoffs are abrupt or poorly communicated (Kelly, 2023).

- Remaining employees often report lower morale, trust, and job satisfaction, along with survivor guilt and fear of future layoffs (SHRM, 2024; Nectar, 2025).

- Chronic job insecurity is linked to burnout, mental health decline, and reduced productivity (Hammer et al., 2024; López Bohle et al., 2016).

Organizational communication scholars emphasize that transparent messaging, affirmation of employee value, and supportive leadership can buffer the negative effects of downsizing. When employees feel heard and respected—even amid uncertainty—they are more likely to maintain resilience and engagement (Deetz, 1992; Jablin, 1987).

Coping Strategies for Life Transitions

To support employees navigating life changes and downsizing, organizations can:

- Offer Employee Assistance Programs (EAPs) and mental health resources

- Promote resilience training and stress management workshops

- Encourage open dialogue and normalize emotional responses to change

- Provide flexible work arrangements and transitional support

Practices such as yoga, mindfulness, and structured reflection have also been shown to reduce cortisol levels and improve emotional regulation during periods of upheaval (MSN Health, 2025).

Workplace Strategy Pack

How Stressed are You?: Managing Workplace Stress

Purpose: To help employees and organizations identify, understand, and manage workplace stress using organizational communication strategies and validated self-assessment tools.

Understanding Workplace Stress

Workplace stress arises when job demands exceed an individual’s capacity to cope, often exacerbated by poor communication, lack of control, and unclear expectations. Chronic stress can lead to burnout, decreased productivity, and health issues (American Institute of Stress, 2024).

Organizational communication plays a critical role in either mitigating or amplifying stress. Transparent messaging, supportive feedback, and inclusive dialogue foster psychological safety and resilience (Rajhans, 2009).

“How Stressed Are You?” Inventory

Adapted from the American Institute of Stress (2024), this inventory helps individuals assess their current stress levels at work.

Instructions

Rate each statement based on how often it applies to your current job:

| Statement | Never | Rarely | Sometimes | Often | Very Often |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conditions at work are unpleasant or unsafe | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| My job negatively affects my physical or emotional well-being | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| I have too much work or unreasonable deadlines | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| I find it difficult to express my opinions to superiors | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Job pressures interfere with my personal life | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| I have inadequate control over my work duties | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| I receive inadequate recognition for good performance | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| I am unable to fully utilize my skills and talents | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

Scoring

- 8–15: Low stress

- 16–20: Fairly low stress

- 21–25: Moderate stress

- 26–30: High stress

- 31–40: Severe stress—consider seeking support

Strategies to Reduce Workplace Stress

| Strategy | Description |

|---|---|

| Improve Communication | Use clear, consistent messaging and active listening to reduce ambiguity. |

| Encourage Feedback | Create safe channels for employees to voice concerns and suggestions. |

| Promote Autonomy | Allow employees control over how they complete tasks. |

| Recognize Contributions | Offer timely, specific praise and rewards. |

| Support Work-Life Balance | Encourage breaks, flexible schedules, and boundary-setting. |

Communication Tip

“Stress thrives in silence. Open, empathetic communication is the antidote.” — Inspired by Rajhans (2009)

References

American Institute of Stress. (2024). Workplace stress scale. https://www.stress.org/self-assessments/workplace-stress-scale/

Rajhans, K. (2009). Effective organizational communication: A key to employee motivation and performance. Interscience Management Review, 2(2), 81–85. https://www.interscience.in/imr/vol2/iss2/13

Headington Institute. (2020). How stressed are you? Self-assessment inventory. https://www.headington-institute.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/R32-Stress-Test-Eng.pdf

5. Downsizing and Job Insecurity: Organizational Stress Amplified

Among major life changes, downsizing is one of the most disruptive in organizational contexts. It affects not only those who lose their jobs but also those who remain—often referred to as “survivors”—who may experience guilt, anxiety, and increased workload (Moore et al., 2004). These ripple effects can erode trust, morale, and long-term engagement.

A landmark study by the U.S. Department of Labor found that:

- 59% of companies downsized at least once between 1980–1994

- Manufacturing firms had the highest rate of downsizing (25%)

- Retail and service sectors followed at 17% and 15%, respectively (Slocum et al., 1999)

More recent research confirms that downsizing continues to be a chronic organizational stressor, especially in volatile industries and during economic downturns. The consequences include:

- Elevated psychological strain, absenteeism, and burnout (Kalimo, Taris, & Schaufeli, 2003; APA, 2025)

- Declines in creativity and innovation, particularly in environments lacking psychological safety (Amabile & Conti, 1999; Lipman, 2024)

- Increased alcohol use, emotional exhaustion, and reduced performance among employees facing job insecurity (Probst et al., 2007; Sikora et al., 2008)

Job insecurity—whether real or perceived—can trigger pre-traumatic stress responses, including hypervigilance, rumination, and avoidance behaviors (Shehab, 2025). These effects are especially pronounced when layoffs are sudden, poorly communicated, or perceived as unfair.

Communication as a Buffer

Organizational communication scholars emphasize that transparent messaging, affirmation of employee value, and supportive leadership can buffer the negative effects of downsizing (Wisenfeld et al., 2001; Kaiser, 2018). When employees feel heard and respected—even amid uncertainty—they are more likely to maintain resilience and engagement.

Best practices include:

- Early and honest communication about organizational changes

- Clear rationale for decisions and acknowledgment of emotional impact

- Supportive messaging that affirms employee contributions and dignity

- Access to mental health resources, career counseling, and transitional support

When downsizing is handled with empathy and clarity, organizations can preserve trust and reduce the long-term damage to culture and performance (APA, 2025; Hammer et al., 2024).

6. Unwritten Rules and Ambiguous Communication

In many workplaces, stress doesn’t just come from formal expectations—it emerges from unspoken norms, ambiguous messaging, and unclear feedback loops. These invisible dynamics, often referred to as unwritten rules, shape how employees behave, communicate, and advance—but they can also create confusion, anxiety, and exclusion (Travis, 2013; Robinson, 2024). Unwritten rules are informal expectations about behavior, communication, and performance that are not documented but widely understood—often through observation or trial and error. Examples include:

- Knowing when it’s “okay” to leave work

- Understanding how to respond to vague Slack messages like “hey”

- Navigating office politics or visibility expectations

- Interpreting silence from leadership as approval or disapproval

These rules often vary by team, manager, or culture, and they disproportionately affect new employees, remote workers, and those from underrepresented backgrounds (Fosslien & Duffy, 2020; Catalyst, 2013).

Ambiguous Communication and Its Effects

Ambiguous communication—such as unclear instructions, vague feedback, or inconsistent messaging—can lead to:

- Cognitive overload and second-guessing

- Reduced psychological safety

- Misinterpretation of tone or intent, especially in digital formats

- Stress from uncertainty, especially when stakes are high

A 2024 Workhuman study found that 60% of employees encounter unwritten rules that negatively impact their ability to communicate and connect with colleagues. Ambiguity in communication is especially problematic in hybrid and remote environments, where tone and context are harder to interpret (Robinson, 2024).

Coping Strategies and Organizational Solutions

To reduce stress from unwritten rules and ambiguous communication, organizations can:

Organizational Practices

- Document informal norms: Create “It’s okay to…” lists to clarify expectations (Fosslien & Duffy, 2020; HBR, 2020)

- Establish communication protocols: Define response time expectations, preferred channels, and tone guidelines

- Train managers in inclusive messaging: Encourage clarity, empathy, and regular check-ins

- Use AI-powered tools to flag potentially harmful or unclear language (Robinson, 2024)

Individual Coping Strategies

- Seek feedback proactively: Ask for clarification when expectations are unclear

- Observe team dynamics: Learn norms by watching how successful colleagues communicate

- Build informal networks: Mentors and peers can help decode hidden expectations

- Practice assertive communication: Express needs and boundaries respectfully

7. Toxic Team Dynamics and Poor Collaboration

Toxic team dynamics and poor collaboration are among the most damaging stressors in organizational life. They erode trust, disrupt communication, and create environments where employees feel isolated, defensive, or unsafe—all of which contribute to chronic stress, disengagement, and turnover (APA, 2024; Davey, 2025).

Toxic teams are often characterized by:

- Lack of psychological safety: Employees fear speaking up, admitting mistakes, or offering feedback (Inclusion Geeks, 2024; FullTilt, 2024)

- Broken trust: Leaders micromanage, play favorites, or avoid accountability

- Communication breakdowns: Passive-aggressive emails, vague instructions, and gossip replace honest dialogue

- Unresolved conflict: Tension simmers beneath the surface, leading to resentment and avoidance

- Values drift: Teams lose sight of shared goals and begin rewarding individual heroics over collaboration

These dynamics don’t just affect morale—they corrode performance, increase absenteeism, and stifle innovation (Sloan Management Review, 2022; Psychology Today, 2024).

Collaboration Under Pressure

Stress amplifies dysfunction. When teams are under pressure:

- Communication becomes reactive and rushed

- Trust erodes as members become guarded or combative

- Decision-making suffers from groupthink or conflict escalation

- Creativity declines as teams revert to safe, familiar routines (Inclusion Geeks, 2024)

Poor collaboration is often rooted in misaligned goals, unclear roles, and lack of empathy—especially in hybrid or remote settings where visibility and tone are harder to interpret (Emergenetics, 2024; Forbes, 2024).

Coping Strategies and Organizational Solutions

To repair toxic dynamics and foster healthy collaboration, organizations can:

Organizational Practices

- Build psychological safety: Encourage open dialogue, normalize feedback, and protect vulnerability (McKinsey, 2023)

- Clarify roles and goals: Use shared planning tools and regular check-ins to align expectations

- Address conflict directly: Train teams in productive conflict and emotional regulation

- Audit team culture: Use diagnostics to identify dysfunction and track progress (Davey, 2025)

Individual Coping Strategies

- Detach from drama: Focus on your work and avoid toxic energy

- Seek allies: Build cross-functional relationships outside your immediate team

- Practice self-care: Engage in hobbies, mindfulness, and reflection to maintain emotional balance

- Know when to exit: If toxicity persists and leadership is unresponsive, consider strategic career moves

8. Digital Communication Overload: The Hidden Cost of Constant Connectivity

In today’s digital-first workplace, communication overload has emerged as a major stressor—particularly in hybrid and remote environments. While platforms like email, Slack, Teams, and project management apps were created to facilitate collaboration, their overuse has led to fragmented attention, mental fatigue, and emotional burnout (Brosix, 2023; Together Platform, 2023). Digital communication overload occurs when the volume, frequency, and complexity of messages—across multiple digital channels—exceed an individual’s capacity to process them effectively. Common contributors include:

- Constant notifications from multiple apps

- Pressure to respond immediately

- Difficulty managing multiple communication streams

- Misinterpretation of tone or intent in text-based messages

Employees now spend approximately 28% of their workweek managing emails alone, with interruptions occurring every 11 minutes and a 25-minute recovery period after each (Brosix, 2023).

Effects on Employees

| Impact Area | Consequences |

|---|---|

| Mental Health | Anxiety, irritability, and burnout from constant digital stimuli |

| Productivity | Reduced focus, slower decision-making, and missed deadlines |

| Creativity | Limited time for deep work and innovative thinking |

| Work-Life Boundaries | Blurred lines between personal and professional time, especially after hours |

Remote workers are especially vulnerable, with 58% reporting pressure to remain digitally available beyond formal work hours (YAROOMS, 2022).

Coping Strategies and Organizational Solutions

Organizational Practices

- Define clear digital communication expectations and respect off-hours

- Streamline tools to minimize redundancy (YAROOMS, 2022)

- Encourage asynchronous communication to reduce urgency (HRD Connect, 2024)

- Implement communication norms such as “quiet hours” or “no-message blocks”

- Audit digital workflows and eliminate bottlenecks (Together Platform, 2023)

Individual Coping Strategies

- Mute non-essential notifications during high-focus tasks

- Adopt digital detox routines, such as screen-free evenings

- Set personal boundaries and communicate them respectfully

- Practice mindfulness to restore focus and emotional regulation

- Seek human connection through mentorship and voice/video meetings

9. Misaligned Leadership Styles

Leadership is one of the most powerful forces shaping workplace climate—and when leadership style doesn’t align with employee needs, team culture, or organizational goals, it becomes a source of stress rather than a solution (Shrivastava, 2022; Aslan, Sönmez, & Deniz, 2025). A misaligned leadership style occurs when a leader’s approach clashes with:

- The needs or readiness of their team

- The demands of the situation

- The culture or values of the organization

For example, a hands-off, laissez-faire leader may frustrate a team that craves structure and guidance, while an overly directive manager may stifle creativity in a team that thrives on autonomy (Northouse, 2021; Hutchens, 2025).

Consequences of Misalignment

| Area of Impact | Consequences |

|---|---|

| Employee Well-being | Increased stress, anxiety, and burnout due to unclear expectations or lack of support |

| Morale and Trust | Erosion of confidence, disengagement, and feelings of entrapment |

| Performance | Poor decision-making, inefficiency, and missed goals |

| Culture | Fragmentation, conflict, and high turnover |

Leadership Styles and Stress

Recent research shows that:

- Charismatic and democratic leaders foster positive climates and reduce stress through clear communication and shared decision-making (Aslan et al., 2025).

- Autocratic and laissez-faire leaders increase stress and feelings of entrapment, especially when employees lack control or clarity (Shrivastava, 2022; Hutchens, 2025).

- Situational leadership, while flexible, can backfire if leaders misjudge team readiness or shift styles inconsistently (Northouse, 2021).

Coping Strategies and Organizational Solutions

Organizational Practices

- Assess leadership fit: Use 360-degree feedback and climate surveys to identify misalignment

- Train leaders in emotional intelligence and adaptive communication

- Clarify decision-making authority and expectations to reduce ambiguity

- Create team agreements that define how leaders and teams collaborate (Moementum, 2025)

Individual Coping Strategies

- Practice self-reflection: Identify your preferred leadership style and communication needs

- Seek clarity: Ask for specific expectations and feedback

- Set boundaries: Protect your time and energy when leadership is inconsistent

- Build resilience: Use journaling, mentorship, and mindfulness to manage emotional strain

10. Cultural and Generational Misalignment

In today’s diverse and multigenerational workplaces, cultural and generational misalignment has emerged as a subtle but powerful source of stress. These misalignments occur when employees’ values, communication styles, and expectations clash with those of their organization or colleagues—often unintentionally. The result? Confusion, disengagement, and emotional strain that can ripple across teams and departments (Nilsen, 2023; Short, 2024). Cultural misalignment happens when an organization’s stated values (e.g., collaboration, transparency, innovation) don’t match its lived practices. For example:

- A company that promotes “well-being” but rewards overwork

- A team that claims to value “diversity” but tolerates microaggressions

- A manager who preaches “respect” but routinely interrupts others

These disconnects erode trust and fuel conflict. Employees may feel disoriented, cynical, or emotionally distant—especially when they can’t reconcile what’s said with what’s done (Short, 2024; Workplace Peace Institute, 2024).

Generational Misalignment: A Growing Divide

With up to five generations now working side by side—from Silent Generation to Gen Z—differences in values, work habits, and communication styles are inevitable. Misalignment often stems from:

- Communication preferences: Boomers may prefer formal meetings, while Gen Z favors quick chats and emojis (Inclusion Geeks, 2024)

- Work-life expectations: Gen X may value flexibility for caregiving, while Millennials seek purpose and feedback

- Technology fluency: Digital natives may feel frustrated by slower tech adoption among older colleagues

These differences can lead to misunderstandings, stereotyping, and interpersonal tension—especially when leaders fail to acknowledge or adapt to generational needs (Pulivarthi Group, 2025; EdStellar, 2025).

Consequences of Misalignment

| Type of Misalignment | Common Outcomes |

|---|---|

| Cultural Misalignment | Disengagement, passive resistance, high turnover, conflict |

| Generational Misalignment | Miscommunication, reduced collaboration, stereotype-driven bias |

Both forms of misalignment can lead to burnout, quiet quitting, and loss of innovation—especially when employees feel unseen or misunderstood.

Coping Strategies and Organizational Solutions

Organizational Practices

- Audit lived culture vs. stated values: Use behavior-based diagnostics to identify gaps (Nilsen, 2023)

- Create inclusive communication norms: Blend formal and informal styles to meet generational needs

- Offer intergenerational mentoring: Pair younger and older employees for mutual learning (EdStellar, 2025)

- Train leaders in cultural humility: Encourage listening, empathy, and adaptive leadership (Short, 2024)

Individual Coping Strategies

- Clarify expectations: Ask for specifics when values or norms feel unclear

- Practice cultural agility: Learn to navigate different styles and values with curiosity

- Build bridges: Seek allies across generations and cultures to foster understanding

- Speak up respectfully: Share feedback when misalignment affects your well-being

The Impact of Stress: From Health to Performance

Stress doesn’t just affect how we feel—it reshapes how we think, behave, and perform. In organizational contexts, stress manifests across three interconnected domains: psychological, physiological, and work-related outcomes. These domains influence everything from emotional well-being and physical health to productivity, decision-making, and interpersonal dynamics.

Understanding these dimensions is essential for leaders, teams, and individuals seeking to build resilient, high-performing workplaces. When stress is chronic or unmanaged, it can lead to burnout, illness, and disengagement. But when recognized and addressed proactively, stress can be reframed as a signal for change, adaptation, and support.

In the sections that follow, we’ll explore how stress affects:

- Psychological outcomes: including mood, cognition, and emotional regulation

- Physiological outcomes: such as cardiovascular strain, immune suppression, and sleep disruption

- Work outcomes: including performance, engagement, absenteeism, and turnover

Each area offers insight into how stress operates—and how communication, leadership, and wellness strategies can mitigate its effects.

1. Physiological Outcomes of Stress: What Happens Inside the Body

Stress is not just a feeling—it’s a full-body experience. When triggered, the body initiates a cascade of physiological responses designed to help us survive immediate threats. But in modern organizational life, these responses are often activated by non-life-threatening stressors like deadlines, meetings, or interpersonal conflict. Over time, this chronic activation can lead to serious health consequences.

How the Body Reacts to Stress

When faced with stress, the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis releases hormones like cortisol and adrenaline, which:

- Increase heart rate and blood pressure

- Suppress digestion and immune function

- Alter breathing patterns and muscle tension (American Psychological Association, 2023; Williamson, 2025)

These changes are adaptive in the short term—part of the classic “fight or flight” response—but when stress becomes chronic, they contribute to:

- Cardiovascular strain (e.g., hypertension, increased risk of stroke)

- Musculoskeletal pain (e.g., tension headaches, back pain)

- Gastrointestinal issues (e.g., bloating, constipation, acid reflux)

- Immune suppression, making individuals more vulnerable to illness (APA, 2023; Psychreg, 2025)

Chronic Stress and Long-Term Health

Prolonged exposure to stress hormones can:

- Accelerate skin aging and trigger flare-ups of conditions like psoriasis and acne (Grossbart, 1992)

- Disrupt sleep cycles, leading to fatigue and cognitive decline

- Contribute to metabolic disorders such as obesity and diabetes

- Increase risk for cardiovascular disease, especially when paired with unhealthy coping behaviors like smoking or poor diet (CPH-NEW, 2024; Talkspace, 2024)

While the direct link between stress and heart attacks remains complex, behavioral patterns associated with stress—such as sedentary lifestyle and poor nutrition—are well-established risk factors (APA, 2023).

Coping Strategies for Physiological Stress

To counteract the physical toll of stress, organizations and individuals can adopt:

- Mindfulness and breathing exercises to regulate cortisol levels

- Physical activity to reduce muscle tension and improve cardiovascular health

- Sleep hygiene practices to restore immune and cognitive function

- Nutrition education to prevent stress-related eating habits

- Workplace wellness programs that promote movement, hydration, and recovery breaks (APA, 2023; CDC, 2024)

2. Psychological Outcomes of Stress: Mental Health in the Workplace

Stress doesn’t just wear down the body—it reshapes the mind. Chronic workplace stress is strongly linked to depression, anxiety, emotional exhaustion, and cognitive strain, all of which can impair decision-making, relationships, and overall well-being (American Psychological Association, 2024; Workplace Mental Health, 2024).

How Stress Affects the Brain

Persistent stress activates the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, flooding the brain with cortisol and disrupting neurotransmitter balance. This can:

- Impair emotional regulation and increase irritability

- Reduce concentration and memory

- Heighten rumination and worry

- Lead to sleep disturbances, which further exacerbate mental strain (Mayo Clinic Staff, 2008; CDC, 2024)

Over time, these changes can contribute to clinical depression, generalized anxiety disorder, and burnout—a state of emotional depletion that affects motivation, empathy, and engagement (Workplace Mental Health, 2024).

Mental Health Statistics

- 33% of Americans report stress accompanied by depression symptoms (APA, 2022)

- 83% of U.S. workers currently feel work-related stress, with many citing emotional fatigue and irritability (Workplace Mental Health, 2024)

- Chronic stress is associated with decision fatigue, social withdrawal, and substance use as coping mechanisms (OSHA, 2024)

Coping Strategies for Psychological Stress

To protect mental health in high-stress environments, organizations and individuals can adopt:

Organizational Practices

- Normalize mental health conversations and reduce stigma

- Offer Employee Assistance Programs (EAPs) and counseling resources

- Train managers to recognize signs of emotional strain and respond empathetically

- Promote job enrichment and meaningful work to boost morale

Individual Coping Strategies

- Practice mindfulness and meditation to regulate emotions

- Build support networks inside and outside of work

- Use journaling or therapy to process stress

- Prioritize sleep, movement, and hobbies that restore emotional balance

3. Work Outcomes of Stress: Performance, Commitment, and Turnover

Stress doesn’t just affect health—it reshapes how people show up at work. Chronic stress is consistently linked to declines in job performance, lower organizational commitment, and higher turnover rates (Cropanzano, Rupp, & Byrne, 2003; Podsakoff et al., 2007). It influences both in-role performance (how well employees fulfill their formal duties) and organizational citizenship behaviors—the extra, voluntary efforts that help teams thrive (Gilboa et al., 2008).

Negative Work Outcomes

When stress becomes overwhelming or unmanaged, employees may experience:

- Reduced productivity and focus

- Emotional exhaustion, leading to disengagement

- Irritability and conflict with coworkers or customers

- Presenteeism, where employees are physically present but mentally depleted

- Increased absenteeism and turnover, especially in high-stress industries like healthcare and hospitality (Pham, 2024; OSHA, 2024; Shah, 2023)

A recent report from the American Psychological Association (2025) found that stressed employees are more likely to report low motivation, desire to quit, and fatigue-related errors.

The Paradox of Challenge Stressors

Not all stress is harmful. Research shows that moderate levels of challenge stressors—such as tight deadlines or complex tasks—can actually enhance performance for some individuals (Podsakoff, LePine, & LePine, 2007). The key is to stay within the activation zone, where stress energizes rather than exhausts (Quick et al., 1997).

When challenge stressors are paired with:

- Autonomy

- Supportive leadership

- Clear goals and feedback

…employees are more likely to rise to the occasion and perform at higher levels (LeggUP, 2024; Shah, 2023).

Coping Strategies for Work-Related Stress

Organizational Practices

- Promote work-life balance and flexible scheduling

- Offer mental health resources and Employee Assistance Programs (EAPs)

- Encourage recognition and feedback to boost morale

- Monitor workload distribution and adjust unrealistic demands

Individual Coping Strategies

- Use time management tools to break tasks into manageable steps

- Practice mindfulness and regular breaks to sustain focus

- Set boundaries to protect personal time

- Seek support from mentors or supervisors when demands feel overwhelming

Why We Experience Stress Differently: Personality, Culture, and Communication Style

Stress is not a one-size-fits-all experience. How individuals perceive, respond to, and recover from stress is shaped by a complex interplay of personality traits, cultural background, and communication style—each influencing emotional regulation, coping strategies, and workplace dynamics.

1. Personality and Stress Response

Personality plays a central role in how stress is experienced and expressed. The classic Type A vs. Type B framework still offers insight, but modern research expands the conversation:

- Type A personalities are characterized by urgency, competitiveness, and impatience. These traits correlate with higher stress reactivity, especially in high-pressure environments. Hostility and hyper-reactivity are particularly linked to negative outcomes like burnout and cardiovascular strain (Spector & O’Connell, 1994; Ganster, 1986).

- Type B personalities tend to be more reflective and relaxed, showing lower physiological arousal in stressful situations and better emotional regulation.

Contemporary models like the Big Five Personality Traits offer deeper nuance:

- Neuroticism is strongly associated with stress sensitivity and emotional instability.

- Conscientiousness and agreeableness are linked to proactive coping and resilience (O’Brien & DeLongis, 1996; Carver & Connor-Smith, 2010).

2. Cultural Influences on Stress

Culture shapes how stress is interpreted and managed. For example:

- Collectivist cultures (e.g., Japan, India) may emphasize harmony and suppress emotional expression, leading to internalized stress.

- Individualist cultures (e.g., U.S., U.K.) often encourage assertiveness and emotional disclosure, which can buffer stress through social support (Hofstede, 2001; Triandis, 1995).

Cultural norms also influence coping styles:

- Problem-focused coping is more common in Western contexts.

- Emotion-focused or avoidance coping may be more prevalent in Eastern or high-context cultures.

3. Communication Style and Stress

Communication style affects how individuals express stress, seek support, and navigate conflict:

- Assertive communicators tend to manage stress more effectively by setting boundaries and expressing needs clearly.

- Passive or passive-aggressive styles may lead to unresolved tension and internalized stress (Gupta, 2023; Zurnamer, 2025).

- Aggressive communicators may externalize stress, creating toxic dynamics and interpersonal strain.

Personality traits like introversion vs. extraversion also influence communication preferences and stress vulnerability. Introverts may internalize stress and avoid confrontation, while extraverts may seek social outlets for relief (16Personalities, 2024).

Coping Strategies Across Differences

To support diverse stress responses, organizations and individuals can:

Organizational Practices

- Promote inclusive communication norms that respect different styles

- Offer flexible wellness programs tailored to personality and cultural needs

- Train managers in emotional intelligence and cultural humility

Individual Strategies

- Practice self-awareness to understand your stress triggers and coping style

- Use adaptive communication to express needs and seek support

- Build cross-cultural empathy to reduce misinterpretation and conflict

Workplace Strategy Pack

Appropriate Stress Outlets

Objective: To equip employees and organizations with effective, research-backed outlets for managing workplace stress through communication, culture, and wellness strategies.

Why Stress Outlets Matter

Workplace stress is a leading contributor to burnout, absenteeism, and reduced productivity. According to the American Institute of Stress, it costs U.S. businesses over $300 billion annually in lost productivity and healthcare expenses.

Organizational communication plays a pivotal role in shaping how stress is experienced and managed. Supportive communication, participatory decision-making, and transparent feedback loops are essential for fostering resilience and psychological safety (Scott, n.d.; Kaiser, 2018).

Appropriate Stress Outlets

Here are evidence-based outlets that help employees manage stress effectively:

1. Open Communication Channels

- Regular check-ins and feedback sessions

- Anonymous suggestion boxes or digital platforms

- Supervisor training in active listening and empathy

“Positive communication and job satisfaction are strong predictors of lower stress levels and fewer cooperation breaches.” — Kaiser (2018)

2. Mindfulness & Relaxation Programs

- On-site or virtual meditation sessions

- Breathing exercises and guided imagery

- Quiet rooms or wellness spaces

3. Physical Activity Opportunities

- Walking meetings or stretch breaks

- Subsidized gym memberships or fitness classes

- On-site yoga or movement workshops

4. Peer Support Networks

- Mentorship programs

- Employee resource groups (ERGs)

- Informal lunch-and-learn sessions

5. Flexible Work Arrangements

- Remote work options

- Flexible scheduling

- Encouragement of boundary-setting (e.g., no emails after hours)

6. Stress Management Training

- Workshops on time management, resilience, and coping skills

- Cognitive-behavioral strategies for reframing stress

- Conflict resolution and assertiveness training

Organizational Communication Strategies

| Strategy | Impact on Stress Reduction |

|---|---|

| Transparent Messaging | Reduces ambiguity and uncertainty |

| Participatory Decision-Making | Enhances control and ownership |

| Recognition & Feedback | Boosts morale and self-efficacy |

| Supervisor Support | Builds trust and emotional resilience |

| Conflict Resolution Systems | Prevents escalation and promotes psychological safety |

References

American Institute of Stress. (2023, May 5). How to address workplace stress for employee well-being. https://www.stress.org/news/how-to-address-workplace-stress-for-employee-well-being/

Kaiser, F. (2018). Understanding stress in communication management: How it limits the effectiveness at personal and organizational level. In B. Peña-Acuña (Ed.), Digital communication management. IntechOpen. https://www.intechopen.com/chapters/61136

Scott, C. R. (n.d.). Communication, social support, and burnout: A brief literature review. University at Buffalo School of Social Work. https://socialwork.buffalo.edu/content/dam/socialwork/home/self-care-kit/readings/communication-social-support-and-burnout.pdf

American Psychological Association. (2024, October 22). Coping with stress at work. https://www.apa.org/topics/healthy-workplaces/work-stress

Sutton, J. (2021). Workplace stress management: 11 best strategies & worksheets. PositivePsychology.com.. https://positivepsychology.com/workplace-stress-management/

Insider Edge

Surviving a Toxic Workplace That Pits Employees Against Each Other

Objective: To equip employees with actionable strategies, grounded in organizational communication research, for navigating and resisting toxic workplace dynamics that deliberately induce stress through manipulation and division.

Understanding the Toxic Dynamic

Toxic workplaces often weaponize stress by fostering competition, favoritism, and distrust. When leadership pits employees against one another, it creates a hostile climate that undermines collaboration, psychological safety, and well-being (Sleek, 2024; Schoenbeck, 2020).

This tactic—sometimes called “divide and conquer management”—is used to maintain control, suppress dissent, and prevent collective resistance. It erodes morale, increases burnout, and drives high turnover (Al Soqair & Al Gharib, 2023).

Signs of Intentional Toxicity

| Behavior | Impact on Employees |

|---|---|

| Favoritism and exclusion | Fuels resentment and insecurity |

| Gossip and rumor encouragement | Breaks trust and unity |

| Withholding information | Creates confusion and competition |

| Public comparisons and shaming | Undermines confidence and collaboration |

| Rewarding sabotage or aggression | Normalizes unethical behavior |

Insider Edge Strategies

1. Build a Micro-Community of Trust

- Identify allies who share your values

- Create informal support networks

- Share information transparently among trusted peers

“Coworker support moderates the effects of toxic leadership and builds resilience.” — Al-Hassani (2025)

2. Practice Strategic Communication

- Document interactions with toxic leaders

- Use neutral, professional language

- Avoid gossip and reactive behavior

3. Clarify Your Values and Boundaries

- Define your ethical limits

- Refuse to participate in divisive tactics

- Use assertive communication to protect your integrity

4. Focus on Psychological Detachment

- Use mindfulness and cognitive reframing

- Avoid internalizing toxic narratives

- Engage in restorative activities outside work

5. Manage Up and Document

- Keep a record of toxic incidents

- Communicate concerns through formal channels

- Seek HR or legal guidance if necessary

Empowerment Tip

“Leadership has nothing to do with rank. You can embody the leader you wish you had.” — Simon Sinek (2024)

References

Al Soqair, N., & Al Gharib, F. (2023). Toxic workplace environment and employee engagement. Journal of Service Science and Management, 16(6), 661–669. https://doi.org/10.4236/jssm.2023.166035

Al-Hassani, K. (2025). The effect of toxic leadership on job stress and organizational commitment: The moderating role of coworker support. Indiana Journal of Economics and Business Management, 5(1), 52–63. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14779926

Schoenbeck, D. (2020). How to tolerate and outflank an overly competitive coworker. https://daveschoenbeck.com/how-to-tolerate-and-outflank-an-overly-competitive-coworker/

Sleek, S. (2024, June 27). Toxic workplaces leave employees sick, scared, and looking for an exit. American Psychological Association. https://www.apa.org/topics/healthy-workplaces/toxic-workplace

Sinek, S. (2024, February 28). Simon’s tips for combating a toxic work culture. The Optimism Company. https://simonsinek.com/stories/simons-tips-for-combating-a-toxic-work-culture/

Discussion Questions

- How might the three phases of General Adaptation Syndrome (GAS)—alarm, resistance, and exhaustion—manifest during common workplace challenges such as unclear expectations, heavy workloads, or interpersonal conflict? Think beyond physical strain: what emotional, cognitive, or relational signals might indicate movement from one stage to the next?

- Identify two real or hypothetical work scenarios where prolonged exposure to stress could push someone from the resistance phase into exhaustion. Consider factors such as leadership style, lack of recovery time, digital overload, or toxic team dynamics.

- What are some effective time management and boundary-setting strategies that help mitigate work-related stress? Reflect on practices that support deep focus and wellbeing—like digital detox windows, mindfulness breaks, or flexible scheduling.

- Stress can show up in many ways—physically, emotionally, and behaviorally. Based on what you’ve learned, what symptoms have you noticed in yourself or others during high-pressure times at work? Include subtle signs like changes in communication tone, creativity decline, irritability, or disengagement.

Section 7.3: Thriving Under Pressure: Communication-Based Approaches to Managing Stress

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, you should be able to do the following:

- Identify effective individual strategies for stress management, such as mindfulness, workload management, and recognizing flow states.

- Analyze organizational approaches to reducing stress, including supportive leadership, fair practices, and flexible work policies.

- Evaluate the role of communication during change and crisis as a tool for reducing uncertainty and fostering trust.

- Explore the potential of emerging technologies like virtual reality and machine learning in enhancing personalized stress management and empathetic communication in hybrid work environments.

Individual Approaches to Managing Stress

The Corporate Athlete: Expanding a High-Performance Model

Stress isn’t just an obstacle—it can be a catalyst for growth. Jack Groppel, a professor of kinesiology and bioengineering at the University of Illinois, recognized that elite athletes didn’t merely endure stress; they trained to thrive under pressure. Inspired by these principles, he introduced the Corporate Athlete model: a framework that helps professionals optimize physical, emotional, and mental energy to achieve peak performance in demanding environments (Groppel & Andelman, 2000).

By adopting proactive rituals—such as nutrition, exercise, sleep, and mindset conditioning—Corporate Athletes don’t just react to stress; they train for it. This approach treats stress as a potential asset: a force that can be converted from distress to eustress, the kind that fuels motivation and creativity (Franks, 2023; APA Dictionary of Psychology, n.d.).

While the model’s foundation remains powerful, today’s workforce faces new challenges that demand expanded strategies. Emerging research in cognitive science, mindfulness, and resilience suggests that individual stress management requires both physical readiness and psychological agility. Modern professionals must not only build strong bodies and minds—they must also cultivate awareness, self-regulation, and connection to effectively navigate workplace pressure (Cásedas, Schooler, Vadillo, & Lupiáñez, 2024; Ferguson, Dinh-Williams, & Segal, 2021; Linder & Mancini, 2021).

What follows is a blended approach: the Corporate Athlete model enhanced with insights from mindfulness, resilience science, and cognitive reframing—giving individuals a full-spectrum toolkit to thrive in high-stress environments.

Flow: Turing Stress into Engagement

Transforming stress into fuel for corporate athleticism is one way to convert a potential adversary into a workplace ally. Another powerful strategy is to break challenges into manageable parts and embrace those that spark joy. In doing so, individuals can enter a state reminiscent of a child at play—fully immersed in the task at hand, losing track of time, and experiencing a deep connection to the challenge before them.

This state of total engagement is known as flow, a concept introduced by psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi. Flow is defined as a state of consciousness in which a person is completely absorbed in an activity, experiencing a sense of control, clarity, and intrinsic motivation (Csikszentmihalyi, 1990). It’s the mental zone where we feel strong, alert, and effortlessly focused.

According to Csikszentmihalyi, the most pleasurable way to work is in harmony with one’s true interests. Work, when approached this way, resembles play—filled with tasks, puzzles, surprises, and rewarding challenges. By breaking down a busy workday into smaller, meaningful pieces, individuals can shift from the “stress” of work to a more engaged and fulfilling state of flow.

Together, corporate athleticism and flow offer complementary pathways for managing stress: one through physical and mental conditioning, the other through psychological immersion and joy. Next, we’ll explore how individual lifestyle choices—such as nutrition, exercise, sleep, and time management—can further reduce stress and enhance performance.

Figure 7.5

| High Focus | 20% of managers are disengaged at work | 10% of managers engage in purposeful work |

|---|---|---|

| Low Focus | 30% of managers are procrastinators | 40% of managers are distracted at work |

| Low Energy | High Energy |

A key to flow is engaging at work, yet research shows that most managers do not feel they are engaged in purposeful work.

Sources: Adapted from information in Bruch, H., & Ghoshal, S. (2002, February). Beware the busy manager. Harvard Business Review, 80, 62–69; Schiuma, G., Mason, S., & Kennerley, M. (2007). Assessing energy within organizations. Measuring Business Excellence, 11, 69–78.

Designing Work That Flows

Keep in mind that work that flows includes the following:

- Challenge: the task is reachable but requires a stretch

- Meaningfulness: the task is worthwhile or important

- Competence: the task uses skills that you have

- Choice: you have some say in the task and how it’s carried out (Csikszentmihalyi, 1997)

Diet: Fueling the Brain for Peak Performance

What we eat doesn’t just affect our bodies—it directly influences our mental sharpness and stress resilience. Greasy, high-fat foods often leave us feeling sluggish. Why? Because fats take longer to digest, prompting the body to divert blood flow toward the stomach and away from the brain, which can reduce alertness and energy levels.

Similarly, consuming large, heavy meals in the middle of the day may slow cognitive performance. The body prioritizes digestion, pulling resources from mental processing to physical breakdown. In contrast, lighter meals rich in lean protein and omega-3 fatty acids—like wild salmon—can enhance brain function. Fish supports the production of dopamine and norepinephrine, two neurotransmitters associated with alertness, concentration, and faster reaction times (Wurtman & Wurtman, 1988).

By choosing foods that support neurotransmitter activity, individuals can better manage stress and maintain mental clarity throughout the day. Diet, when aligned with performance goals, becomes a strategic tool—not just a source of fuel.

Exercise: Energizing the Mind and Body

Movement isn’t just about physical fitness—it’s a catalyst for mental clarity, emotional regulation, and sustained energy. Regular physical activity stimulates the release of endorphins and serotonin, which elevate mood and reduce stress. But beyond the emotional lift, exercise enhances oxygen flow to the brain, improving focus, memory, and decision-making under pressure.

Sedentary behavior, especially during long workdays, can lead to mental fatigue and sluggishness. When the body remains inactive, circulation slows, and so does cognitive performance. In contrast, even short bursts of movement—like a brisk walk or stretching session—can re-energize the mind by increasing blood flow and activating neural pathways associated with alertness and creativity.

High-intensity interval training (HIIT), yoga, and resistance workouts have all been shown to improve executive function and resilience. According to Ratey (2008), exercise acts as “Miracle-Gro for the brain,” promoting neurogenesis and enhancing the brain’s ability to adapt and recover from stress.

By integrating purposeful movement into daily routines, individuals can sharpen their mental edge and build physical stamina. Exercise, when aligned with performance goals, becomes a strategic asset—not just a wellness checkbox.

Sleep: Breaking the Stress-Fatigue Cycle

Sleep and stress are deeply intertwined in a cycle that can be difficult to escape. Stress disrupts sleep, and poor sleep amplifies stress—leading to reduced focus, irritability, and impaired decision-making. Sleep deprivation doesn’t just affect individual performance; it can ripple through teams, elevating tension and reducing overall productivity.

Insomnia is a widespread issue in the U.S., with approximately one-third of adults reporting difficulty sleeping (Hamilton, Catley, & Karlson, 2007). The consequences extend beyond the workplace. According to the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, 684 fatalities in 2021 were linked to drowsy driving—an 8.2% increase from the previous year (Stewart, 2023).

The modern work–life crunch makes restorative sleep feel elusive. Research published in the journal Sleep found that workers suffering from insomnia are significantly more likely to miss work due to exhaustion, costing employers an estimated $1,967 per employee annually—a figure that adds up to over $100 billion in lost productivity across industries (Rosekind et al., 2010).

This cycle is self-reinforcing: employees who miss work due to fatigue often return to heavier workloads, compounding stress and further disrupting sleep. Addressing sleep health isn’t just a personal wellness issue—it’s a strategic imperative for organizations seeking to reduce burnout and improve performance.

Create a Social Support Network: Building Resilience Through Connection

One of the most consistent findings in stress research is that individuals with strong social support networks experience significantly lower stress levels than those without such connections. Social support acts as a buffer, helping individuals cope more effectively with workplace demands and emotional strain (Halbesleben, 2006; Van Yperen & Hagedoorn, 2003).

Support can come from many sources—coworkers, supervisors, friends, and family—and each plays a unique role in reducing stress. In the workplace, fostering a team-oriented atmosphere where colleagues encourage and assist one another can build a culture of shared resilience. Outside of work, simply having someone to talk to and listen to—whether a friend, partner, or family member—can provide emotional relief and perspective.

By cultivating these relationships, individuals not only reduce their own stress but also contribute to a more supportive and emotionally intelligent work environment. Social support isn’t just a comfort—it’s a strategic resource for well-being and performance.

Time Management: Reclaiming Control and Reducing Stress

Time management refers to the development and use of tools or techniques that help individuals work more efficiently and productively. It’s not just about getting more done—it’s about reducing the pressure that comes from feeling overwhelmed. When faced with information overload and competing responsibilities, it’s easy to fall into reactive habits, constantly responding to urgent tasks while neglecting important ones.