Chapter 8: Communication

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, you should be able to do the following:

- Describe the key components of the communication process and explain how they interact.

- Analyze and differentiate between various types of communication (e.g., verbal, nonverbal, written, visual).

- Evaluate the effectiveness of different communication channels in organizational contexts.

- Identify common barriers to effective communication and develop strategies to overcome them.

- Explain the importance of active listening and demonstrate techniques that enhance listening effectiveness.

- Assess how ethical considerations influence both the delivery and interpretation of messages in the workplace.

- Interpret how verbal and nonverbal cues may carry different meanings across cultures and design communication strategies that promote intercultural understanding.

Section 8.1: Spotlight

Communication Breakdown During St. Louis’s Spring 2025 Snow and Ice Response

In early 2025, a prolonged winter storm left residential streets and sidewalks in St. Louis dangerously coated in ice and snow. Residents across neighborhoods—especially in Tower Grove South and Botanical Heights—reported inaccessible roads, delayed trash pickup, and limited city response for over a week. The situation drew criticism not just for the operational delays, but for the communication failures that amplified public frustration. The organizational communication process lacked clarity and cohesion, with residents unsure of priorities, timelines, and available resources (City of St. Louis, 2025).

The city’s use of communication channels was fragmented and inadequate. While general updates appeared on the official city website and occasional press releases, social media posts were sporadic, and there was little effort to communicate through traditional methods like radio or printed notices for digitally disconnected populations. The city’s snow route maps and tiered plans were neither clearly communicated nor referenced in public messaging, making it difficult for residents to understand city priorities or monitor progress (FOX2Now, 2025; Spectrum News, 2025).

Several barriers to effective communication emerged, including unclear budgeting decisions and staffing shortages within the Streets Department. For example, reallocations from snow removal to pothole maintenance were not explained to the public until after widespread concern had surfaced (St. Louis Public Radio, 2025). This reactive rather than proactive communication fueled public mistrust. Additionally, the absence of multilingual updates and ADA-accessible formats revealed shortcomings in inclusive communication design.

The role of listening was largely absent throughout the snow response. Unlike scenarios involving robust community engagement, the city did not seek real-time feedback or consult neighborhood leaders during the early stages of the crisis. As a result, residents in underserved communities resorted to funding private plow services—highlighting a breakdown in institutional responsiveness and dialogue (St. Louis Public Radio, 2025). The lack of feedback mechanisms such as online surveys, public hotlines, or virtual town halls further hampered organizational adaptability.

Ethically, the city’s messaging was seen as uninspired and insensitive. Public statements focused on staffing constraints rather than the lived impact of icy conditions, contributing to a perception of indifference. Verbal messages lacked empathy, and nonverbal communication—including the absence of city vehicles and officials in affected areas—reinforced the notion that residential neighborhoods were a lower priority. This disconnect between leadership and constituents strained public confidence during an already precarious situation (FOX2Now, 2025).

In summary, the City of St. Louis’s 2025 snow and ice response underscores the importance of strategic, inclusive, and empathetic organizational communication in municipal operations. Aligning logistical execution with transparent and responsive messaging is critical—not only for managing crises effectively but also for sustaining public trust.

References

City of St. Louis. (2025). Snow and ice response and maintenance. https://www.stlouis-mo.gov/government/departments/street/street-division/snow-ice/index.cfm

FOX2Now. (2025, January 13). Some St. Louis neighborhoods left icy and unplowed. https://fox2now.com/news/missouri/some-st-louis-neighborhoods-left-icy-and-unplowed/

Spectrum News. (2025, February 5). St. Louis County’s snow response struggled due to volume, lack of experienced staff. https://spectrumlocalnews.com/mo/st-louis/news/2025/02/05/st-louis-county-transportation-public-works-snow-removal

St. Louis Public Radio. (2025, January 14). Lack of staff and equipment held up St. Louis area snow removal. https://www.stlpr.org/government-politics-issues/2025-01-14/modot-st-louis-lack-of-staff-equipment-streets-unplowed

Discussion Questions

- The City of St. Louis used inconsistent communication channels during the snow and ice response. How could the city have better utilized diverse communication methods to ensure all residents—especially those without internet access or with language barriers—received timely and actionable information?

- Staffing shortages and budget reallocations were cited as barriers to the city’s snow removal efforts. How could proactive communication about these challenges have mitigated public frustration? What strategies can organizations use to address barriers transparently without eroding trust?

- Residents resorted to crowdfunding private plow services due to a lack of institutional support. What does this suggest about the city’s listening practices during the crisis? How can organizations create feedback loops to better respond to community needs in real time?

- The city’s messaging was criticized for being impersonal and overly focused on logistical constraints. How does the tone and content of communication impact public trust during a crisis? What ethical considerations should leaders prioritize when crafting messages in high-stakes situations?

- The absence of visible leadership in affected neighborhoods was perceived as a lack of prioritization. How do nonverbal cues, such as physical presence and visible action, influence public perception of organizational commitment during a crisis?

Section 8.2: Understanding Communication

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, you should be able to do the following:

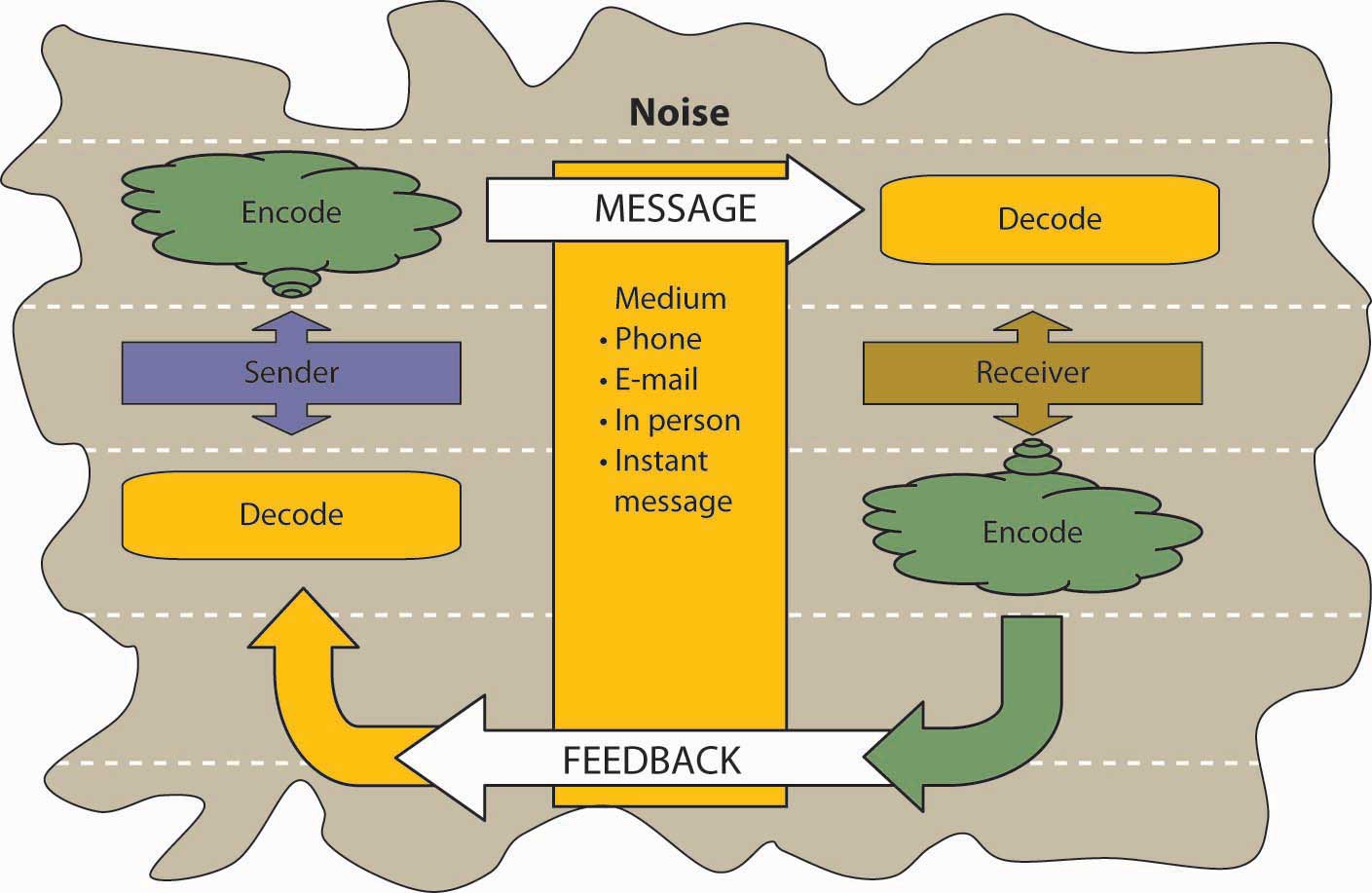

- Identify and explain the key components of communication, including the sender, message, medium, receiver, and feedback.

- Analyze the communication process by recognizing potential breakdowns and obstacles such as miscommunication, noise, and ineffective messaging.

The Communication Process

Communication is the lifeblood of organizational functioning—it enables coordination, fosters collaboration, and drives goal achievement. Defined by Merriam-Webster as the exchange of information through a common system of symbols, signs, or behavior, communication permeates every level of organizational life. Research consistently shows that managers spend between 50% and 90% of their time communicating (Schnake et al., 1990), and their communication competence is directly linked to performance outcomes (Penley et al., 1991). While miscommunication in typical work settings may result in delays or interpersonal tension, in high-stakes environments such as operating rooms or aviation, it can have life-or-death consequences.

The prevalence and impact of miscommunication are well documented. CRICO Strategies found that communication failures contributed to 30% of 23,000 medical malpractice claims between 2009 and 2013, resulting in 1,744 deaths and $1.7 billion in costs (Budryk, 2016). Moreover, communication style—not just clinical outcomes—can influence litigation risk. A seminal study revealed that physicians with warmer, more personal communication styles were less likely to be sued, even when outcomes were poor (USA Today, 1997). These findings underscore the critical role of interpersonal communication in shaping perceptions and mitigating conflict.

In the business realm, poor communication is a costly liability. According to a 2022 study by The Harris Poll and Grammarly, ineffective communication leads to an average loss of 7.47 hours per employee per week—equating to approximately $12,506 annually per employee (BusinessWire, 2022). Conversely, strong communication skills are highly valued by employers. The National Association of Colleges and Employers (2023) reported that over 60% of employers seek candidates who are collaborative problem-solvers, and 50% prioritize written communication skills. Internally, organizations that keep employees informed and provide access to necessary information see higher levels of job satisfaction (What are the bottom line…, 2003).

Effective internal communication also correlates with financial performance. Meisinger (2003) emphasized that satisfied employees, empowered by transparent communication, are better positioned to serve customers effectively. Supporting this, research shows that improvements in communication integrity can boost market value by up to 7% (Meisinger, 2003). Grensing-Pophal (2006), analyzing data from Watson Wyatt, found that significant enhancements in internal communication quality were associated with a 29.5% increase in market value (Wolf, 2022). These findings illustrate that communication is not merely a soft skill—it is a strategic asset with tangible organizational benefits.

Discussion Questions

- Think of a time when communication broke down in your life—at work, school, or home. What part of the process went wrong? Was the message unclear, the medium ineffective, or the decoding influenced by personal factors?

- How might miscommunication contribute to errors or safety issues in the workplace? Consider industries like healthcare, hospitality, or construction—how could a misunderstood message lead to serious consequences?

- Can you describe an example of “noise” you’ve experienced during a conversation or message exchange? Was it physical (like distractions or background noise), psychological (like stress or assumptions), or semantic (confusing language or jargon)?

Section 8.3: What Gets in the Way: Communication Barriers and Listening Skills

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, you should be able to do the following:

- Identify common barriers that disrupt the communication process, including distractions, biased language, emotional filters, and selective perception.

- Evaluate the impact of poor listening habits on interpersonal and workplace communication, and recognize behaviors that undermine mutual understanding.

- Define active listening and its core components, including attention, empathy, nonverbal engagement, and message confirmation.

- Apply practical strategies to strengthen listening effectiveness, such as paraphrasing, silence for reflection, observation of emotional cues, and asking clarifying questions.

7 Barriers to Effective Communication

In any organization, communication is the lifeblood of collaboration, decision-making, and productivity. Yet despite its central role, communication is often disrupted by a range of barriers that distort meaning, hinder understanding, and reduce efficiency. These barriers can be subtle or overt, and they frequently arise from psychological, semantic, or structural factors within the workplace.

Among the most commonly cited obstacles are filtering, where information is selectively presented to shape perceptions; selective perception, which causes individuals to interpret messages through personal biases; and information overload, which overwhelms the receiver’s ability to process messages effectively (Robbins & Judge, 2017). Emotional states can also interfere, leading to emotional disconnects that block empathy and clarity (Clampitt, 2010). Additionally, lack of source familiarity or credibility can erode trust in the message, while workplace gossip—though informal and widespread—can distort facts and fuel misinformation (Daft, 2016). Finally, semantic barriers, such as jargon or ambiguous language, often result in misinterpretation and confusion (Guffey & Loewy, 2022).

Understanding these barriers is essential for improving communication outcomes. By identifying what gets in the way, organizations can take proactive steps to foster transparency, build trust, and enhance listening skills—ultimately creating a more connected and effective workplace.

1. Filtering: A Barrier to Clear Communication

Filtering refers to the intentional distortion or omission of information to influence how a message is received. This often occurs when individuals aim to manage others’ reactions—especially in hierarchical settings. For example, a manager may withhold negative sales data from a superior, or a gatekeeper may selectively pass along messages to protect reputational interests (Robbins & Judge, 2017). Even the receiver may unconsciously filter by deleting or ignoring messages that seem unpleasant or threatening.

This behavior is particularly common in upward communication, where employees may fear repercussions for sharing bad news. As Clampitt (2010) notes, filtering can prevent organizations from seeing the full picture, leading to poor decision-making and reduced transparency. To counteract this, leaders should encourage open dialogue and reward honesty, even when the message is unfavorable.

Individuals may decide to filter based on several factors:

- Past experience: Whether previous messengers were rewarded or punished.

- Perception of the receiver: If the superior has signaled that bad news is unwelcome.

- Emotional state and confidence: Fear, stress, or lack of expertise may inhibit full disclosure.

- Attention and involvement: Personal distractions or disengagement can distort message evaluation.

Ultimately, filtering contributes to miscommunication and fragmented understanding. As Alessandra (1993) observed, each listener reconstructs a message through their own lens, often creating a version that diverges from the original intent.

2. Selective Perception: Seeing What We Expect to See

Selective perception is the unconscious process of filtering information based on personal needs, experiences, and expectations. In a world saturated with stimuli, individuals naturally prioritize what they notice and how they interpret it. This mental shortcut helps us navigate complexity—but it can also distort communication and lead to misunderstandings (Langton, Robbins, & Judge, 2009).

For example, when visiting a new workplace, small details may stand out. Over time, however, we begin to assume patterns based on prior experiences. These assumptions shape how we interpret messages. In organizational settings, this can be problematic. Consider the case of Bill and his manager: Bill, overwhelmed by a demanding to-do list, assumed a toner request could wait. His manager, believing her urgency was clear, expected immediate action. Both relied on selective perception—and the result was miscommunication.

This bias is especially potent when emotional discomfort or prior beliefs are involved. People may ignore information that contradicts their worldview or focus intensely on details that confirm it (Smith, 2015). In workplace communication, this can manifest as perceptual defense or hyper-vigilance, depending on the context.

To reduce the impact of selective perception, organizations can:

- Encourage diverse perspectives in decision-making.

- Promote feedback loops to clarify intent.

- Train employees in active listening and empathy.

By recognizing this barrier, communicators can take steps to ensure messages are received as intended—rather than filtered through assumptions.

3. Information Overload: When Communication Becomes Too Much

In today’s hyper-connected world, individuals are bombarded with messages from every direction—professional emails, team chats, social media notifications, advertisements, and personal conversations. This constant stream of input can quickly exceed our ability to process it all, leading to a state known as information overload.

Information overload occurs when the volume and complexity of incoming information surpass an individual’s cognitive capacity to absorb and respond (Schick, Gordon, & Haka, 1990). It’s not just about quantity—it’s about the mismatch between what we’re expected to process and the time or mental bandwidth available to do so. In organizational settings, this imbalance can lead to missed messages, delayed decisions, and increased stress.

Recent research highlights the growing scale of the problem. A Gartner survey of nearly 1,000 employees and managers found that 38% of employees feel overwhelmed by excessive communication, while only 13% reported receiving less information in 2022 than the previous year (Klein, Earl, & Cundick, 2023). The proliferation of digital platforms—email, messaging apps, intranets, and productivity tools—has created a maze of channels that employees must navigate daily, often with little guidance or prioritization.

Information overload is more than a nuisance—it’s a strategic risk. It contributes to disengagement, poor decision-making, and reduced productivity (Arnold, Goldschmitt, & Rigotti, 2023). Fragmented workflows and constant interruptions diminish creativity and mental acuity, making it harder for employees to focus on meaningful tasks (Overholt, 2001). Even well-intentioned communication can become noise when it lacks relevance or clarity.

To combat this, organizations are rethinking how they communicate. Strategies include streamlining channels, tailoring messages to specific audiences, and fostering a culture of clarity and intentionality (Earl, 2025). Leaders are also encouraged to audit their communication practices and invest in training that promotes digital literacy and message prioritization.

In short, more communication isn’t always better. The key is to ensure that the right information reaches the right people at the right time—without overwhelming them in the process.

4. Emotional Disconnects: When Feelings Get in the Way of Clarity

Effective communication requires a balance between emotional awareness and clarity of thought from both the sender and the receiver. When emotions run high, this balance is disrupted, leading to emotional disconnects that hinder understanding and collaboration. A sender who is experiencing intense emotions, such as anger or stress, may struggle to articulate ideas effectively, while a receiver in a similarly unsettled state might misinterpret, distort, or even disregard the intended message. This misalignment is especially common in high-stakes or high-stress environments, where emotional regulation may falter and communication deteriorates. Emotional barriers can prevent people from listening with openness and empathy or expressing themselves with precision. In workplaces characterized by pressure and diversity, these disconnects often lead to reduced transparency, misalignment of goals, and disengagement among teams (Ganapathi, 2024). Strategies such as pausing before responding, using “I” statements to convey feelings constructively, and promoting psychological safety can help mitigate these challenges. By creating space for emotional regulation and encouraging active listening, organizations can foster deeper understanding and more effective communication.

5. Lack of Source Familiarity or Credibility / Misperceptions

Communication is not just about the message—it’s also about the messenger. When the sender lacks credibility or familiarity, the receiver may question the intent, tone, or accuracy of the message, leading to misperceptions and communication breakdowns. Humor, sarcasm, and irony are particularly vulnerable to misinterpretation in professional settings, especially when delivered through low-context channels like email. Without shared context or a history of trust, even a lighthearted comment can be perceived as offensive or inappropriate. For instance, a sarcastic remark from a colleague known for exaggeration may be taken literally by someone unfamiliar with their communication style, resulting in confusion or offense. Moreover, if a sender has previously shared inaccurate information or created false alarms, their current messages may be filtered or dismissed entirely. This erosion of trust can significantly impair organizational communication, as receivers become skeptical of the sender’s motives or reliability. As noted by Cragun (2020), source credibility is a critical factor in message acceptance, and misperceptions often arise when emotional tone, context, or sender reputation are unclear. To foster effective communication, organizations must promote transparency, consistency, and relationship-building, ensuring that messages are not only clear but also trusted.

6. Workplace Gossip

Workplace gossip, often referred to as the grapevine, is an informal communication network that plays a significant role in organizational life. While managers may view it as a barrier to effective communication, employees frequently rely on it as a trusted source of information. Research suggests that up to 70% of organizational communication occurs through informal channels like the grapevine (Crampton, 1998; Goman, 2019). Its grassroots nature often lends it more credibility than official messages, even when the information shared is inaccurate. This dynamic can be problematic, especially when gossip is used strategically by insiders to manipulate narratives or promote personal agendas. The lack of a clear sender in gossip exchanges can also breed distrust, particularly when the content is volatile or sensitive. Employees may question the origin and intent behind the message, leading to speculation and tension. Despite its risks, workplace gossip serves important social functions, such as fostering connection, reducing uncertainty, and helping employees make sense of ambiguous situations (Begemann et al., 2023). Managers who understand the power of the grapevine can use it to their advantage—either by engaging with it strategically or by countering misinformation with timely, transparent communication. By acknowledging the grapevine’s influence and responding proactively, leaders can reduce confusion and strengthen organizational trust.

7. Semantics and Jargon

Semantics and jargon are often overlooked yet powerful barriers to effective communication in the workplace. Semantics refers to the meaning of words and how those meanings can vary depending on context, culture, or individual interpretation. Jargon, on the other hand, is the specialized language used within a particular profession or organization. While jargon can serve as a useful shorthand among experts, it can also alienate or confuse those outside the group. For example, acronyms like GBS, BPTS, SOX, and BPO may be second nature to IBM insiders but utterly opaque to outsiders unfamiliar with the company’s internal language. This lack of shared understanding can lead to miscommunication, frustration, and even mistrust. Semantic barriers arise when individuals assign different meanings to the same words or phrases, often due to cultural, linguistic, or experiential differences (Shwom & Snyder, 2022). In professional settings, the misuse of jargon can obscure the intended message, causing listeners to disengage or misinterpret the speaker’s intent (Dudovskiy, 2023). To communicate effectively, it’s essential to consider the audience. When speaking to fellow specialists, jargon may reinforce shared expertise and streamline communication. However, when addressing a broader audience, clarity should take precedence over brevity. Translating technical terms into plain language fosters inclusivity and ensures that the message is received as intended. Ultimately, the goal is not just to speak—but to be understood.

In addition, the OB Toolbox below will help you avoid letting business jargon get in your way at work.

Workplace Strategy Pack

Reducing Miscommunication by Jargon

Objective: To equip employees with actionable strategies to minimize jargon-related miscommunication and foster clearer, more inclusive communication across internal teams and external stakeholders.

The Problem with Jargon

Jargon—specialized or technical language used within a profession—can alienate listeners, obscure meaning, and reduce trust. While it may signal expertise within a group, it often creates confusion and resistance when used with broader audiences (Bullock et al., 2019; Patoko & Yazdanifard, 2014).

“Jargon impairs processing fluency, leading to lower comprehension and increased resistance to persuasion.” — Bullock et al. (2019)

Strategy Toolkit

1. Know Your Audience

- Internal Teams: Use shared terminology only when everyone understands it

- Clients or Cross-Functional Teams: Assume minimal familiarity with your field’s jargon

- Tip: Ask, “Would someone outside my department understand this term?”

2. Translate Jargon into Plain Language

- Replace complex terms with everyday equivalents

- Define necessary technical terms the first time they appear

- Use analogies or examples to clarify abstract ideas

Example: Instead of “synergistic optimization,” say “working together to improve results.”

3. Create a Jargon Glossary

- Develop a shared document of commonly used terms and their plain-language definitions

- Update it regularly and share it with new hires and external partners

4. Practice Processing Fluency

- Use short, active sentences

- Avoid acronyms unless they’re widely known or clearly defined

- Read your message aloud—if it sounds confusing, simplify it

5. Model Clear Communication

- Leaders should set the tone by using accessible language in meetings and emails

- Encourage feedback: Ask others if your message was clear

- Reward clarity over complexity

Empowerment Tip

“Clear communication isn’t about dumbing down—it’s about lifting others up.” — Inspired by Bullock et al. (2019) & Brown et al. (2021)

References

Bullock, O. M., Colón Amill, D., Shulman, H. C., & Dixon, G. N. (2019). Jargon as a barrier to effective science communication: Evidence from metacognition. Public Understanding of Science, 28(7), 845–856. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963662519865687

Patoko, N., & Yazdanifard, R. (2014). The impact of using many jargon words while communicating with organization employees. American Journal of Industrial and Business Management, 4(10), 567–572. https://doi.org/10.4236/ajibm.2014.410061

Brown, Z. C., Anicich, E. M., & Galinsky, A. D. (2021). Does your office have a jargon problem? Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2021/03/do-you-have-a-jargon-problem

Gender Differences in Communication

Gender differences in communication styles can significantly influence workplace dynamics, often leading to misunderstandings if not acknowledged and addressed. Generally, men tend to adopt a more direct, action-oriented approach, often “jumping right in” to tasks, while women are more likely to ask clarifying questions before beginning a project. This contrast can result in misperceptions—for example, a male manager may mistakenly interpret a woman’s thoughtful inquiry as hesitation or lack of readiness. Additionally, men frequently use sports metaphors to convey strategy and motivation, whereas women may draw on domestic or relational analogies. Without shared context, these stylistic choices can create barriers to collaboration and inclusion. Research shows that men often communicate to assert status and convey information, while women prioritize building relationships and fostering cooperation (Coffman & Marques, 2021). These tendencies reflect broader cultural norms and socialization patterns that shape how individuals express themselves. As gender policy advisor Dee Norton emphasized, effective communication across gender lines requires adaptability and mutual respect. Leaders and team members who understand and apply the “rules of gender culture” are better equipped to foster inclusive and productive environments. Recognizing that men may focus more on competition, data, and directives, while women may emphasize intuition, empathy, and collaboration, allows organizations to leverage the strengths of both styles. Rather than viewing these differences as obstacles, they can be embraced as complementary assets that enrich team performance and decision-making.

LGBTQ+ Communication in the Workplace

Modern workplaces are increasingly diverse, and communication styles vary not only by gender but also by sexual orientation, gender identity, and lived experience. LGBTQ+ employees may navigate unique challenges in expressing themselves authentically, especially in environments shaped by traditional gender norms. For example, nonbinary individuals may feel excluded by binary language, while transgender employees might experience microaggressions or misgendering that disrupt communication and trust (Ellsworth et al., 2021).

Inclusive communication requires more than awareness—it demands intentionality. Using gender-neutral language, respecting pronouns, and avoiding assumptions about identity or relationships are foundational practices. Research shows that LGBTQ+ employees are more likely to experience workplace microaggressions and feel pressure to conceal aspects of their identity, which can hinder collaboration and psychological safety (Talkspace, 2025; Maji et al., 2024). Conversely, workplaces that foster allyship, visibility, and inclusive messaging see higher engagement, retention, and innovation.

Organizations can support LGBTQ+ communication by offering training on respectful language, creating employee resource groups, and ensuring that policies and messaging reflect diverse identities. As with gender differences, the goal is not to erase distinctions but to embrace and adapt to them, creating space for every voice to be heard.

Differences in Meaning Between the Sender and Receiver

Communication is not just about delivering a message—it’s about ensuring that the message is understood as intended. One of the most common barriers to effective communication is the difference in meaning between the sender and receiver. These differences can stem from a variety of factors, including age, education, cultural background, professional experience, and emotional context. A phrase that seems clear to one person may be interpreted entirely differently by another. For example, when a manager speaks about “long-term goals and profits” to a team that has experienced stagnant wages, the message may be perceived as dismissive or tone-deaf, even if the intent was motivational. Instead, tailoring the message to acknowledge employees’ contributions and linking those efforts to shared success can foster trust and clarity. According to Clearinfo (2024), sender-oriented barriers such as assumptions, vague language, and lack of audience awareness often lead to misinterpretation and disengagement (Clearinfo, 2024). Similarly, LibreTexts (2025) emphasizes that each listener translates a message through their own lens, shaped by personal experiences and expectations (LibreTexts, 2025). To bridge these gaps, communicators must prioritize clarity, empathy, and audience awareness—choosing words that resonate with the receiver’s perspective rather than relying solely on their own.

Biased Language

Biased language refers to words or expressions that stereotype individuals or groups based on personal attributes such as race, gender, age, ability, or political affiliation. Such language can undermine respectful communication and perpetuate harmful assumptions. For example, referring to someone solely by a characteristic—such as “a diabetic” or “a brain”—reduces their identity to a single trait, which can be dehumanizing and dismissive. In professional settings, biased language not only damages interpersonal relationships but may also violate civil rights standards and corporate policies (Ashcraft & Mumby, 2003; Miller & Swift, 1980). The rise of politically correct language has sparked debate: while advocates argue that inclusive terminology promotes dignity and reduces harm, critics claim it can feel overly cautious or artificial (Procter, 2007). Regardless of perspective, the goal of effective communication is to be clear, factual, and respectful. Many organizations now provide employees with speech and conduct guidelines to foster inclusive environments. These resources, combined with empathy and common sense, help individuals navigate sensitive topics and avoid unintentional offense. Practical strategies include alternating gendered pronouns when speaking generally, consulting HR-approved language guides, and recognizing that what feels respectful to one person may not feel that way to another. Ultimately, respectful language is not just about avoiding offense—it’s about fostering understanding and equity in every interaction.

Figure 8.6

| Avoid | Consider Using |

|---|---|

| black attorney | attorney |

| businessman | business person |

| chairman | chair or chairperson |

| cleaning lady | cleaner or maintenance worker |

| male nurse | nurse |

| manpower | staff or personnel |

| secretary | assistant or associate |

Poor Listening

The greatest compliment that was ever paid to me was when one asked me what I thought, and attended to my answer. —Henry David Thoreau

A sender may strive to deliver a message clearly. But the receiver’s ability to listen effectively is equally vital to successful communication. The average worker spends 55% of their workdays listening. Managers listen up to 70% each day. Unfortunately, listening doesn’t lead to understanding in every case.

From a number of different perspectives, listening matters. Former Chrysler CEO Lee Iacocca lamented, “I only wish I could find an institute that teaches people how to listen. After all, a good manager needs to listen at least as much as he needs to talk” (Iacocca & Novak, 1984). Research shows that listening skills were related to promotions (Sypher, Bostrom, & Seibert, 1989).

Listening clearly matters. Listening takes practice, skill, and concentration. Alan Gulick, a Starbucks Corporation spokesperson, believes better listening can improve profits. If every Starbucks employee misheard one $10 order each day, their errors would cost the company a billion dollars annually. To teach its employees to listen, Starbucks created a code that helps employees taking orders hear the size, flavor, and use of milk or decaffeinated coffee. The person making the drink echoes the order aloud.

How Can You Improve Your Listening Skills?

Listening is a foundational skill in effective communication, yet it is often overlooked in favor of speaking. Cicero once said, “Silence is one of the great arts of conversation,” a sentiment that underscores the importance of truly hearing others. In many conversations, individuals fall into the trap of “rehearsing”—mentally preparing their response while the other person is still speaking. This behavior signals a lack of genuine engagement and undermines the communication process. In contrast, active listening involves giving full attention to the speaker, seeking to understand their message, asking clarifying questions, and avoiding interruptions (O*NET Resource Center, n.d.). It transforms communication from a transactional exchange into a relational experience, where both parties feel heard and respected. Active listening also enhances empathy, builds trust, and improves message accuracy. For example, repeating and confirming a message’s content—such as in a customer service interaction—can ensure clarity and reduce misunderstandings. Practicing active listening requires mindfulness, patience, and a willingness to prioritize understanding over response. In doing so, individuals foster stronger relationships and more effective collaboration in both personal and professional settings.

How Can We Listen Actively?

Active listening is a powerful communication skill that fosters understanding, empathy, and connection. Carl Rogers, a pioneer in humanistic psychology, outlined five essential components of active listening: listen for message content, listen for feelings, respond to feelings, note all cues, and paraphrase and restate (Rogers & Farson, 1987). These principles emphasize the importance of tuning into both verbal and nonverbal elements of communication. The good news is that listening is not an innate talent—it’s a skill that can be learned and strengthened over time (Brownell, 1990). The first step is intentionality: deciding to listen with full attention. This involves eliminating distractions, both external and internal, and receiving the speaker’s message silently and respectfully. Throughout the conversation, listeners should demonstrate engagement through nonverbal cues like nodding and maintaining eye contact, as well as verbal affirmations such as “I see” or “That makes sense.” Observing the speaker’s body language can also provide valuable emotional context. Silence plays a crucial role in active listening—it allows space for reflection and prevents reactive responses. When clarity is needed, listeners should ask thoughtful questions and confirm understanding by paraphrasing key points. For example, repeating a detail like “So we’re meeting at 2:00 p.m. in your office?” ensures accuracy and shows attentiveness. Ending the exchange with mutual appreciation, such as a simple “thank you,” reinforces respect and collaboration.

Becoming a More Effective Listener

Becoming a more effective listener requires intentional effort and practice. While active listening fosters stronger relationships and mutual respect between speakers and receivers, it also enhances collaboration and message accuracy in the workplace. Many organizations invest in public speaking courses, yet few emphasize the equally vital skill of “public listening.” Effective listening involves more than hearing words—it requires attention to tone, body language, and emotional cues. Communication “freezers,” such as interrupting, rehearsing responses, or dismissing others’ perspectives, can shut down dialogue and erode trust. To counter these habits, listeners should focus on being present, suspending judgment, and responding with empathy. According to Bodie (2023), competent listening preserves both the content and relational intent of a message, helping individuals construct shared realities and deepen interpersonal connections. Psychology research also highlights 16 key behaviors of good listeners, including attentiveness, openness, and conversational sensitivity (Whitbourne, 2024). By cultivating these traits and practicing mindful engagement, individuals can transform everyday conversations into opportunities for growth, understanding, and collaboration.

Workplace Strategy Pack

Listening Instead of Reacting

Objective: To help employees develop listening skills that foster understanding, reduce conflict, and improve workplace relationships—especially in emotionally charged situations.

Why Listening Matters More Than Reacting

In emotionally tense moments, many employees default to defensiveness or offense. But research shows that active listening—the process of attentively receiving, interpreting, and responding to messages—can reduce misunderstandings, build trust, and improve organizational outcomes (Yip & Fisher, 2022; Arshad, 2023).

“Listening is not passive. It’s a strategic, interpersonal skill that underpins leadership, collaboration, and innovation.” — Yip & Fisher (2022)

Strategy Toolkit: How to Practice Good Listening

1. Pause Before Reacting

- Take a breath before responding

- Ask yourself: “What is this person really trying to say?”

- Avoid interrupting or mentally preparing your rebuttal

2. Use Reflective Listening

- Paraphrase what you heard: “So you’re saying you felt excluded during the meeting?”

- Ask clarifying questions: “Can you help me understand what led to that feeling?”

3. Listen for Emotion, Not Just Content

- Pay attention to tone, body language, and emotional cues

- Acknowledge feelings: “It sounds like that was frustrating for you.”

4. Separate Intent from Impact

- Don’t assume malice—ask for context

- Recognize that people communicate differently based on culture, personality, and stress levels

5. Practice Empathic Listening

- Focus on understanding the speaker’s perspective

- Avoid judgment or evaluation while listening

- Respond with compassion, not correction

Empowerment Tip

“Listening is the most overlooked leadership skill. It’s how we turn conflict into connection.” — Parks (2020)

References

Arshad, R. (2023, January 5). The importance of listening for organizational success. Forbes Business Development Council. https://www.forbes.com/councils/forbesbusinessdevelopmentcouncil/2023/01/05/the-importance-of-listening-for-organizational-success/

Parks, E. S. (2020). Listening with empathy in organizational communication. Colorado State University Center for Public Deliberation. https://cpd.colostate.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/48/2020/06/Listening_with_empathy_in_organizational.pdf

Yip, J., & Fisher, C. M. (2022). Listening in organizations: A synthesis and future agenda. Academy of Management Annals, 16(2), 657–679. https://doi.org/10.5465/annals.2020.0367

What to Avoid in Workplace Dialogue

Communication freezers are statements or tones that halt productive conversation by making the listener feel judged, dismissed, or attacked. These behaviors often trigger defensiveness and reduce psychological safety in teams (Gibb, 1961; Arshad, 2023).

-

Common Communication Freezers

❌ Phrase or Behavior 🧠 Why It’s Harmful “You always…” / “You never…” Overgeneralizes and blames; shuts down nuance “That’s not true.” Invalidates the speaker’s experience “You’re being too sensitive.” Dismisses emotional reality; triggers shame “Calm down.” Implies irrationality; escalates tension “You should…” / “You must…” Feels controlling; reduces autonomy “That’s just how it is.” Signals unwillingness to engage or change “Why didn’t you…” Implies incompetence; focuses on blame “I don’t want to hear it.” Cuts off communication; signals rejection Sarcasm or mocking tone Undermines trust; creates emotional distance Interrupting or talking over Disrespects speaker; signals disinterest Psychological Impact

These phrases often activate defensive communication patterns, which reduce openness and collaboration. According to Gibb’s (1961) seminal work on defensive climates, behaviors like evaluation, control, and superiority foster resistance rather than resolution.

“Defensive climates inhibit communication, while supportive climates encourage it.” — Gibb (1961)

What to Do Instead

- Use open-ended questions: “Can you tell me more about what happened?”

- Practice reflective listening: “It sounds like you felt left out during the meeting.”

- Validate emotions: “I can see why that would be frustrating.”

- Focus on shared goals: “Let’s figure out how we can improve this together.”

References

Arshad, R. (2023, January 5). The importance of listening for organizational success. Forbes Business Development Council. https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbesbusinessdevelopmentcouncil/2023/01/05/the-importance-of-listening-for-organizational-success/

Gibb, J. (1961). Defensive communication. Journal of Communication, 11(3), 141–148. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.1961.tb00344.x

Organizational Behaviour KPU. (2020). 8.3 Communication barriers. In Organizational Behaviour Exercises and Cases. https://pressbooks.bccampus.ca/obweirexercisesandcases/chapter/8-3-communication-barriers/

Discussion Questions

- Active listening is a skill that can be learned. Do you agree or disagree? Based on your experience, what factors make someone a truly effective listener?

- Think of a time when a message you shared was misunderstood due to differences in age, background, or context. How did the situation unfold, and what could have improved mutual understanding?

- How do you typically respond when you receive workplace communication (like emails or memos) with noticeable grammar issues, typos, or unclear phrasing? Does it impact your trust or perception of the sender’s credibility? Why or why not?

- Selective perception refers to interpreting messages based on your own biases, expectations, or experiences. Can you share a situation where your perception filtered or distorted the intended message?

- Jargon can streamline communication among specialists—but can become a barrier in diverse settings. Do you use jargon in your professional or academic environment? Has it ever helped or hindered communication with others outside your field?

Section 8.4: Different Types of Communication and Channels

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, you should be able to do the following:

- Identify and analyze diverse forms of organizational communication, including verbal, nonverbal, written, and digital modalities, and their roles in fostering engagement, clarity, and trust.

- Evaluate the impact of communication channels—ranging from face-to-face to asynchronous digital formats—on message richness, effectiveness, and contextual appropriateness in professional settings.

- Describe and differentiate communication flows within organizations (upward, downward, lateral, and external), emphasizing how listening cultures, employee advocacy, and strategic messaging influence directionality.

- Explain the role of cross-cultural and global considerations in shaping inclusive and respectful organizational communication practices.

- Assess contemporary trends such as employee voice, change communication, crisis messaging, and the measurement of communication outcomes, highlighting their strategic significance to organizational success.

Communication in the workplace isn’t just about what’s said—it’s about how it’s said and through what means. Every message travels along a particular channel, and the nature of that channel—whether face-to-face, written, digital, or nonverbal—greatly affects how the message is interpreted and acted upon. Understanding the different types of communication (verbal, nonverbal, written, and visual) and the channels available to deliver them is essential for organizational effectiveness.

For instance, verbal communication is immediate and dynamic, enabling real-time feedback, while written communication provides permanence and clarity but lacks emotional nuance. Visual elements like diagrams and infographics enhance comprehension, especially for complex data, and nonverbal cues—like body language and tone—often convey more than words themselves (Clampitt, 2010; Robbins & Judge, 2017). Selecting the right communication channel requires considering factors such as urgency, complexity, audience, and the desired impact of the message (Guffey & Loewy, 2022).

As organizations increasingly blend in-person and digital environments, mastering the interplay between communication types and channels becomes vital. The goal is not just to convey information, but to do so effectively, respectfully, and strategically.

Types of Communication

Effective communication in organizations encompasses more than just spoken or written words—it involves a dynamic interplay of multiple modalities that shape how messages are delivered, interpreted, and acted upon. Contemporary organizational research identifies four primary types of communication: verbal, written, visual, and nonverbal (Guffey & Loewy, 2022; Robbins & Judge, 2017; Valamis, 2025). Each type plays a distinct role in facilitating understanding, collaboration, and decision-making across diverse workplace contexts.

- Verbal communication involves the use of spoken language to convey meaning and foster interaction. It is the most immediate and interactive form, allowing for real-time feedback and emotional nuance through tone, pitch, and pacing (Clampitt, 2010).

- Written communication provides structure and permanence, enabling detailed documentation and asynchronous exchange of information. It is especially critical in remote and hybrid work environments where clarity and professionalism are paramount (Guffey & Loewy, 2022).

- Visual communication has emerged as a vital category in the digital age, leveraging images, charts, infographics, and multimedia to enhance comprehension and engagement. It is particularly effective for presenting complex data and transcending language barriers (Valamis, 2025).

- Nonverbal communication includes body language, facial expressions, gestures, and vocal tone. Often operating subconsciously, it conveys attitudes and emotions that may reinforce—or contradict—verbal messages (Robbins & Judge, 2017).

Understanding these four types of communication equips professionals to choose the most appropriate method for their message, audience, and context. As organizations become more digitally integrated and globally connected, mastering these communication forms is essential for building trust, driving performance, and fostering inclusive collaboration.

1. Verbal Communication

Verbal communication remains one of the most immediate and impactful forms of interaction in the workplace. It involves the use of spoken language—whether face-to-face, over the phone, or through virtual platforms—to convey information, express emotion, and build relationships. In organizational settings, verbal exchanges are essential for clarifying expectations, resolving conflicts, and fostering collaboration (Clampitt, 2010; Brink & Costigan, 2015).

Consider the following example: A manager calls an employee named Bill to request a purchase. The conversation begins with a personalized greeting and recognition of Bill’s contributions, which helps establish rapport and emotional connection. The manager then clearly outlines the task, including quantity, vendor, budget, and deadline. Bill responds by paraphrasing the request, demonstrating active listening and confirming understanding. This feedback loop is a hallmark of effective verbal communication, ensuring that both parties are aligned and reducing the risk of miscommunication (Adu-Oppong & Agyin-Birikorang, 2014).

Beyond transactional exchanges, storytelling is a powerful verbal tool that helps shape organizational culture. Stories communicate values, illustrate best practices, and foster a shared sense of identity. Research shows that the frequency, tone, and strength of organizational stories are positively correlated with employee commitment and entrepreneurial success (McCarthy, 2008; Martens, Jennings, & Devereaux, 2007).

However, not all verbal communication is created equal. High-stakes conversations—such as negotiating a raise or pitching a business plan—require greater preparation, emotional intelligence, and strategic framing. These interactions often involve divergent opinions and heightened emotions, making it crucial to adopt inclusive language (e.g., using “and” instead of “but”) and remain flexible in communication style (Patterson et al., 2002). Under stress, individuals may default to rigid patterns, so cultivating adaptability is key to maintaining clarity and connection.

Ultimately, verbal communication is more than just talking—it’s about listening, responding, and co-creating meaning in real time. When done well, it builds trust, drives performance, and strengthens the social fabric of the organization.

Workplace Strategy Pack

From Offense to Dialogue

Objective: To equip employees with the mindset and tools to move beyond personal offense and engage in meaningful, solution-oriented conversations that strengthen collaboration and trust.

Why Setting Aside Offense Matters

Taking offense is a natural emotional response—but when it dominates workplace interactions, it can lead to defensiveness, resentment, and breakdowns in communication. Research shows that reconciliation and rich dialogue are more likely when individuals shift from blame to curiosity and from judgment to empathy (Marian et al., 2021; Onasanya, 2021).

“Reconciliation is based on a complex socio-occupational mechanism, while revenge stems from negative attributional patterns.” — Marian et al. (2021)

Strategy Toolkit: How to Move Past Offense

1. Reframe the Trigger

- Ask: “What else could this mean?”

- Consider intent vs. impact—most workplace missteps are unintentional

- Avoid assuming malice or disrespect

2. Use Attribution Awareness

- Recognize your own biases in interpreting others’ behavior

- Shift from “They meant to hurt me” to “Maybe they were stressed or unaware”

- This reduces emotional escalation and opens space for dialogue (Marian et al., 2021)

3. Initiate Rich Conversation

- Use “I” statements: “I felt overlooked when my idea wasn’t acknowledged.”

- Ask open-ended questions: “Can we talk about what happened in the meeting?”

- Focus on shared goals and mutual understanding

4. Build Psychological Safety

- Avoid sarcasm, blame, or dismissive language

- Validate others’ perspectives even if you disagree

- Encourage feedback and model humility

5. Practice Conflict Resilience

- Accept that conflict is inevitable and can be constructive

- Use it as a catalyst for growth, not division

- Stay present and curious, not reactive

Empowerment Tip

“Conflict is presumed to be a consequence of a breakdown in communication. When managed well, it becomes a stimulant for organizational growth.” — Onasanya (2021)

References

Marian, M. I., Barth, K. M., & Oprea, M. I. (2021). Responses to offense at work and the impact of hierarchical status: The fault of the leader, causal attributions, and social support during the COVID-19 pandemic crisis. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, Article 734703. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.734703

Onasanya, O. O. (2021). Communication and organizational conflict management. Research Journal of Management Practice, 1(5), 1–12. https://www.ijaar.org/articles/rjmp/v1n5/rjmp-v1n5-may21-p15526.pdf

2. Written Communication

Written communication is a cornerstone of modern business operations, offering clarity, permanence, and scalability across organizational contexts. Unlike verbal communication, which is typically synchronous and ephemeral, written messages—whether printed or digital—can be crafted thoughtfully, revisited repeatedly, and shared widely. Common formats include emails, memos, proposals, manuals, and policies, each serving distinct purposes from documentation to persuasion (Keene, 2023; Birchard, 2021).

One of the defining features of written communication is its asynchronous nature: senders and receivers do not need to engage simultaneously. This allows for reflection, editing, and collaboration among multiple contributors before dissemination. It also enables one-to-many communication, reaching entire departments or customer bases with a single message—unlike verbal exchanges, which are often one-to-one or limited in scope (Perry, 2024).

The choice between verbal and written communication should be guided by the intent of the message. Written formats excel at conveying facts, instructions, and formal documentation, while verbal communication is better suited for expressing emotion, building rapport, and navigating ambiguity (Lee & Hatesohl, 2008). For example, a manager delivering a speech may speak at 125–150 words per minute, but listeners can process 400–500 words per minute—leaving cognitive space for distraction. Written communication mitigates this by allowing readers to control the pace and revisit key points (Lee & Hatesohl, 2008).

In today’s workplace, writing is not just a skill—it’s a professional imperative. According to the National Commission on Writing, 67% of salaried employees in large U.S. companies have writing responsibilities, and 91% of employers consider writing skills when hiring (Flink, 2007). Strong writing enhances credibility, reduces misunderstandings, and supports strategic goals.

To write effectively, simplicity is key. As Thomas Jefferson advised, “Don’t use two words when one will do.” Research confirms that concise, specific, and well-structured writing activates readers’ cognitive reward systems, making messages more memorable and persuasive (Birchard, 2021). Overwriting, on the other hand, can obscure meaning and diminish impact.

Ultimately, written communication is more than just putting words on a page—it’s about crafting messages that inform, inspire, and endure.

3. Visual Communication

Visual communication has become an essential tool in modern organizations, offering a powerful way to convey complex ideas quickly, clearly, and memorably. Unlike verbal or written communication, which relies on language and linear processing, visual elements—such as charts, infographics, videos, and illustrations—tap into the brain’s innate ability to process images rapidly and intuitively. Research shows that the human brain processes visuals up to 60,000 times faster than text, and 90% of information transmitted to the brain is visual (Burokas, 2025; Herting, 2025). This cognitive efficiency makes visual communication especially valuable in fast-paced business environments where clarity and engagement are critical.

Visuals also transcend language barriers and literacy levels, making them more inclusive and accessible. For example, PwC’s use of comic-style contracts for seasonal workers significantly improved comprehension and reduced questions, demonstrating how visuals can simplify even legal documentation (PwC, 2017). In strategic contexts, visuals help align teams by turning abstract goals into tangible roadmaps, enhancing collaboration across departments with different expertise and perspectives (Herting, 2025). Moreover, visual storytelling—through diagrams, animations, or even emojis—can evoke emotion, reinforce key messages, and increase retention far more effectively than text alone (TechSmith, 2023).

However, visual communication must be used thoughtfully. Poorly designed visuals can confuse audiences or dilute the message. Experts recommend tailoring visuals to the audience, using color and contrast strategically, and ensuring that design choices support—not distract from—the core message (Berinato, 2016). As artificial intelligence and digital tools continue to evolve, organizations have unprecedented access to real-time data visualization and personalized design. The challenge now lies in using these tools to enhance—not replace—human insight and creativity.

In today’s workplace, visual communication is no longer a “nice-to-have”—it’s a strategic imperative. Whether simplifying data, inspiring teams, or bridging cultural divides, visuals help organizations communicate with clarity, empathy, and impact.

4. Nonverbal Communication

Nonverbal communication is the silent powerhouse behind effective human interaction. While words convey information, nonverbal cues often determine how that information is received, interpreted, and acted upon. These cues include facial expressions, gestures, posture, eye contact, tone of voice, and even attire—each playing a critical role in shaping perceptions and building trust.

Studies show that up to 93% of communication impact comes from nonverbal elements, with only 7% attributed to the actual words spoken (Mehrabian, 1981). This means that tone, pace, and body language can dramatically alter the meaning of a message. For instance, the phrase “I did not tell John you were late” can carry seven different meanings depending on which word is emphasized (Kiely, 1993). Such nuances are especially important in professional settings, where misalignment between verbal and nonverbal signals can lead to confusion or mistrust.

Nonverbal cues also influence hiring decisions. In a landmark study, judges assessed job candidates’ social skills by watching silent video recordings—evaluating gestures, time spent speaking, and dress formality to predict workplace success (Gifford, Ng, & Wilkinson, 1985). Similarly, subtle behaviors like blinking, shifting weight, or shrugging may signal deception or discomfort (Siegman, 1985). These findings underscore the importance of congruence: when body language matches verbal content, communication feels authentic and persuasive.

In customer-facing roles, nonverbal communication can make or break a relationship. Consider two bank officers delivering identical messages—one with warmth and eye contact, the other with poor grooming and disengaged posture. Despite saying the same words, their impact differs dramatically. This example illustrates how nonverbal behavior shapes emotional tone, credibility, and connection.

To communicate effectively, professionals must be aware of their nonverbal signals and ensure they reinforce—not contradict—their spoken words. As organizations become more diverse and digitally connected, mastering nonverbal communication is essential for building rapport, navigating cultural differences, and fostering inclusive environments.

Following are a few examples of nonverbal cues that can support or detract from a sender’s message.

Body Language

Body language is a powerful form of nonverbal communication that conveys emotions, intentions, and credibility—often more effectively than words alone. Simplicity, directness, and warmth in physical cues tend to signal sincerity, which is essential for building trust and rapport in professional and interpersonal settings. For example, a firm handshake with a warm, dry hand is widely interpreted as a sign of confidence and reliability, while a limp or clammy handshake may suggest discomfort or lack of trustworthiness (Patel, 2014). Facial expressions also play a critical role: gnawing one’s lip may indicate uncertainty or anxiety, whereas a direct smile typically conveys confidence and openness (Adams, 2022). Posture, eye contact, and gestures further shape how messages are received. Open body language—such as uncrossed arms, upright posture, and steady eye contact—signals engagement and honesty, while closed-off gestures may unintentionally communicate defensiveness or disinterest (Chadee & Kostić, 2025). Importantly, body language is culturally nuanced; gestures and expressions that are positive in one culture may be misinterpreted in another. Awareness of these subtleties is key to fostering inclusive and effective communication across diverse teams and global contexts.

Eye Contact

Eye contact is a vital component of nonverbal communication, especially in business contexts. In the United States and many Western cultures, maintaining brief but direct eye contact—typically around one to two seconds—is perceived as a sign of trustworthiness, attentiveness, and confidence (Goman, 2013). It helps establish rapport and signals that both parties are engaged in the conversation.

However, cultural norms around eye contact vary significantly. In many East Asian societies, prolonged eye contact may be considered disrespectful or confrontational, particularly when directed toward elders or authority figures (Samovar et al., 2017). Similarly, in some African and Caribbean cultures, averting the gaze can be a gesture of respect, not avoidance (Neuliep, 2021). These differences underscore the importance of cultural sensitivity in global business interactions.

Recent research also highlights the neurosocial impact of eye contact. Studies suggest that mutual gaze can synchronize brain activity between individuals, enhancing emotional connection and collaborative understanding (Koike et al., 2016). In team settings, effective eye contact patterns—such as alternating between the speaker and shared visual aids—can improve clarity and coordination (Richardson et al., 2022).

Understanding and adapting to these nuances is essential for professionals working across cultures. Tailoring eye contact to suit the context not only improves communication but also fosters inclusivity and trust.

Facial Expressions

Facial expressions are among the most immediate and powerful forms of nonverbal communication. The human face is capable of producing thousands of distinct expressions, many of which correspond to hundreds of emotional states (Ekman, Friesen, & Hager, 2008). These expressions serve as silent signals, conveying emotions, intentions, and social cues often faster than words can.

Basic emotions—such as happiness, fear, anger, sadness, surprise, and disgust—are typically associated with specific facial muscle movements. For instance, happiness is linked to an upturned mouth and slightly closed eyes, while fear is often expressed through a wide-eyed stare and open mouth (Ekman & Friesen, 1978). Subtle cues like shifty eyes or pursed lips may suggest distrust or anxiety, influencing how others perceive us in professional and personal settings (Matsumoto & Hwang, 2013).

The impact of facial expressions is nearly instantaneous. Our brains process these cues rapidly, often forming impressions before a single word is spoken (Holler, 2025). This makes facial awareness especially important in business contexts, where first impressions and emotional intelligence play a critical role. Moreover, research supports the facial feedback hypothesis—the idea that changing our facial expression can influence our emotional state. Smiling, even under stress, can reduce cortisol levels and promote a sense of calm (Strack, Martin, & Stepper, 1988).

In high-stakes situations like interviews or presentations, consciously adopting expressions that reflect confidence and openness can enhance both self-perception and how others respond to us. Our faces don’t just reflect emotion—they help shape it.

Posture

Posture is a subtle yet powerful form of nonverbal communication that shapes how we are perceived in professional and interpersonal settings. The way we position our body—whether seated, standing, or in motion—can signal confidence, openness, attentiveness, or disengagement (Patel, 2014). For instance, sitting with the head held high and back straight (but relaxed) often conveys professionalism and self-assurance, while slouching or leaning away may suggest disinterest or insecurity (Pitterman Altman & Nowicki, 2025).

In interview scenarios, experts recommend mirroring the interviewer’s posture—leaning in when they do, settling back when they do—as a way to build rapport and demonstrate active listening (Mehrabian, 1969). This subtle mimicry fosters psychological alignment and can enhance interpersonal connection. Research also shows that open postures, such as uncrossed arms and legs, are associated with positive attitudes and increased accessibility, while closed postures may unintentionally signal defensiveness or discomfort (Machotka, 1965; Suttie, 2023).

Interestingly, posture doesn’t just communicate emotion—it can influence it. Studies suggest that adopting expansive or upright postures can elevate mood, reduce stress, and even improve performance in high-pressure situations (Van Cappellen et al., 2023). This supports the idea that posture is not only expressive but also embodied, shaping both how we feel and how others respond to us.

Touch

Touch is one of the most nuanced and culturally sensitive forms of nonverbal communication. Its meaning varies widely depending on individual preferences, gender norms, and cultural expectations (Burgoon et al., 1992). In business contexts, touch can signal warmth, respect, or dominance—but misinterpretation is common across cultural boundaries.

For example, in Mexico, it’s customary for men to grasp one another’s arm during conversation. Pulling away may be perceived as rude or dismissive (Daud, 2008). In Indonesia, touching someone’s head or using one’s foot to gesture is considered highly offensive, as the head is viewed as sacred and the foot as unclean (Samovar et al., 2017). In parts of East and Southeast Asia, it may be impolite for women to initiate a handshake with men, especially in formal or religious settings (Daud, 2008).

In contrast, Americans often value a firm handshake as a sign of confidence and professionalism. However, overly forceful handshakes—sometimes dubbed “bone-crushers”—can be interpreted as aggressive or domineering, both domestically and abroad (Goman, 2013). Research also shows that touch can communicate compassion, trust, and emotional support, even in brief interactions (Hertenstein et al., 2009).

Importantly, touch is not just expressive—it’s biologically impactful. Studies reveal that touch can reduce stress, activate the brain’s reward centers, and foster cooperation (Keltner, 2010). Yet, because touch is deeply personal and culturally coded, professionals must remain attuned to context and boundaries to avoid unintended offense.

Space (Proxemics)

The physical space between individuals—known as proxemics—plays a crucial role in shaping communication dynamics. Coined by anthropologist Edward T. Hall, proxemics refers to the study of how humans use space as a form of nonverbal communication, and how these spatial norms vary across cultures (Hall, 1966). The distance between speakers often reflects their level of intimacy, social roles, and cultural expectations.

Hall identified four primary zones of interpersonal distance:

| Zone | Distance | Typical Use |

|---|---|---|

| Intimate Distance | 0–18 inches (0–0.45 m) | Close relationships: embracing, whispering |

| Personal Distance | 1.5–4 feet (0.45–1.2 m) | Friends, family, informal conversations |

| Social Distance | 4–12 feet (1.2–3.6 m) | Acquaintances, professional interactions |

| Public Distance | 12+ feet (3.6+ m) | Public speaking, lectures, formal settings |

In business contexts, misjudging spatial boundaries can hinder effective communication. Standing too far away may feel impersonal or disengaged, while standing too close may be perceived as intrusive or inappropriate—especially across cultures with different norms (Kreuz & Roberts, 2019). For example, Middle Eastern cultures often prefer closer conversational distances, while Northern Europeans may favor more personal space (Samovar et al., 2017).

Understanding proxemics helps professionals navigate cross-cultural interactions, avoid misunderstandings, and foster respectful engagement. It’s not just about where you stand—it’s about how your presence is perceived.

Communication Channels

The channel, or medium, used to transmit a message significantly affects how accurately and effectively that message is received. Channels differ in their information richness—the degree to which they convey verbal and nonverbal cues, allow for immediate feedback, and support emotional nuance (Daft & Lengel, 1984). Research shows that effective managers tend to use richer communication channels more frequently than less effective ones (Allen & Griffeth, 1997; Yates & Orlikowski, 1992).

Information Richness of Channels

Figure 8.10

| Information Channel | Information Richness |

|---|---|

| Face-to-face conversation | High |

| Videoconferencing | High |

| Telephone conversation | High |

| E-mails | Medium |

| Handheld devices (texts, apps) | Medium |

| Blogs | Medium |

| Written letters and memos | Medium |

| Formal written documents | Low |

| Spreadsheets | Low |

Information channels differ in their richness.

Sources: Adapted from information in Daft, R. L., & Lenge, R. H. (1984). Information richness: A new approach to managerial behavior and organizational design. In B. Staw & L. Cummings (Eds.), Research in organizational behavior, vol. 6 (pp. 191–233). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press; Lengel, R. H., & Daft, D. L. (1988). The selection of communication media as an executive skill. Academy of Management Executive, 11, 225–232.

Matching Channel to Message

The key to effective communication is aligning the channel with the message’s purpose (Barry & Fulmer, 2004). Written media is ideal when:

- A record is needed

- There’s low urgency

- The sender and receiver are physically separated

- The message is complex and requires time to process

Verbal communication is better when:

- The message is emotional or sensitive

- Immediate feedback is needed

- The message is time-sensitive

- The ideas are simple or can be clarified quickly

E-mail: Popular but Imperfect

E-mail remains one of the most widely used communication tools:

- Over 4.2 billion users globally in 2023, projected to reach 4.5 billion by 2025 (Kiran, 2023)

- 86% of professionals prefer e-mail for business communication (Kiran, 2023)

- 244.5 million Americans use e-mail daily (Kiran, 2023)

- 124.5 billion business e-mails sent and received daily, with 60 billion flagged as spam (Campaign Monitor, in Kiran, 2023)

Despite its reach, e-mail is only medium-rich. It lacks tone, facial expressions, and body language—making it a poor choice for emotional messages. Studies show that readers often miss sarcasm and emotional cues the sender assumes are obvious (Kruger et al., 2005). This gap led to the rise of emoticons, though they’re generally discouraged in professional settings.

Some companies, like Intel, have even implemented “no e-mail Fridays” to encourage richer forms of communication (Isom, 2008).

Workplace Strategy Pack

Workplace Strategy Pack: Navigating Vocal Inflections Across U.S. Regions

Objective: To help employees recognize how regional and cultural differences in vocal inflection and communication style can complicate message interpretation—and to build skills for clearer, more empathetic workplace dialogue.

Why Vocal Inflection Matters

Regional vocal inflections are shaped by historical migration patterns, cultural norms, and linguistic heritage. These differences can complicate decoding in workplace communication, especially when employees interpret tone as a proxy for intent (Zhang & Pell, 2022; Liu, 2016).

“Listeners often rely on vocal tone to infer emotional states, but cultural and regional norms shape both expression and interpretation.” — Zhang & Pell (2022)

Regional Differences in the U.S.

| 🗂️ Region | 🗣️ Vocal Traits | ⚠️ Possible Misinterpretation |

|---|---|---|

| New England | Fast-paced, clipped, direct | May seem abrupt or cold to others |

| Midwest | Warm, measured, polite | May be perceived as passive or evasive |

| South | Drawn-out, melodic, indirect | May be seen as overly casual or vague |

| West Coast | Relaxed, expressive, informal | May be interpreted as unprofessional |

| Pacific Northwest | Soft-spoken, introspective, reserved | May be seen as disengaged or aloof |

| Southwest | Spanish-influenced, twangy, rhythmic | May be seen as informal or regionally niche |

| Great Plains | Sparse, pragmatic, low-emotion delivery | May be perceived as blunt or indifferent |

| Appalachia | Musical cadence, storytelling tone | May be seen as meandering or overly personal |

| Mid-Atlantic | Strong consonants, assertive, fast-paced | May be perceived as aggressive or brusque |

These differences are not just stylistic—they reflect deep cultural norms around politeness, assertiveness, and emotional expression (Liu, 2016).

Strategy Toolkit: How to Decode and Adapt

1. Practice Cultural Listening

- Listen for intent, not just tone

- Ask clarifying questions: “Did you mean that as a suggestion or a directive?”

2. Avoid Tone-Based Assumptions

- Don’t assume someone is angry, rude, or disinterested based solely on vocal inflection

- Consider regional norms before reacting emotionally

3. Use Meta-Communication

- Acknowledge differences: “I know I tend to speak directly—please let me know if that ever feels abrupt.”

- Invite feedback on tone and clarity

4. Build Cross-Regional Empathy

- Learn about colleagues’ backgrounds and communication styles

- Share your own preferences and invite mutual understanding

Empowerment Tip

“Understanding differences in communication styles allows us to revise the interpretive frameworks we use to evaluate culturally different others.” — Liu (2016)

References

Liu, M. (2016). Verbal communication styles and culture. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Communication. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228613.013.162

Zhang, S., & Pell, M. D. (2022). Cultural differences in vocal expression analysis: Effects of task, language, and stimulus-related factors. PLOS ONE, 17(10), e0275915. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0275915

Bryant, G. A. (2021). Vocal communication across cultures: Theoretical and methodological issues. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 377(1859), 20200387. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2020.0387

Direction of Communication Within Organizations

Organizational communication flows in multiple directions—vertical, horizontal, and diagonal—each serving distinct purposes and presenting unique challenges.

- Vertical communication includes both downward (from top management to employees) and upward (from frontline staff to leadership) flows. Downward communication often involves directives, policies, and performance feedback, while upward communication provides insights, concerns, and suggestions from employees (Lunenburg, 2010). However, upward messages may be filtered or deprioritized by higher-status recipients, reducing their impact.

- Horizontal communication occurs between peers or departments at the same organizational level. It facilitates coordination, collaboration, and problem-solving across teams. Research shows that frequent lateral communication can influence key outcomes such as employee turnover and organizational cohesion (Krackhardt & Porter, 1986).