Chapter 9: Teamwork in Action: Managing Group Dynamics in Today’s Workplace

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, you should be able to do the following:

- Recognize and understand group dynamics and development.

- Understand the difference between groups and teams.

- Compare and contrast different types of teams.

- Understand how to design effective teams.

- Explore ideas around teams and ethics.

- Understand cross-cultural influences on teams.

Section 9.1: Spotlight

Teamwork Breakdown in McDonald’s “Made for You” Initiative – St. Louis Metro Region

The “Made for You” initiative launched by McDonald’s in the early 2000s was intended to modernize the company’s food preparation process by offering customized, freshly made products. However, its rollout across several U.S. regions—including multiple franchise locations in the St. Louis metro—highlighted the pitfalls of poorly executed teamwork and ineffective implementation. The system required new kitchen layouts, updated equipment, and changes to long-standing work habits, but regional and store-level teams lacked adequate support and training. According to analysts from Metheus Consultancy (2023), this top-down rollout ignored key operational realities and generated frustration at nearly every level of the organization.

Problems with group dynamics emerged quickly. Corporate leaders mandated the changes without consulting regional managers or frontline employees, which led to a breakdown in trust and communication. Instead of working collaboratively, teams were forced to implement changes they didn’t fully understand or support. Feedback mechanisms were weak or nonexistent, and employees reported feeling voiceless and unsupported (Metheus Consultancy, 2023). Disconnected roles and lack of psychological safety stifled initiative and created friction, eroding morale throughout the regional network.

The team design flaws were equally significant. The new model disrupted assembly-line kitchen operations, slowing service times and confusing team roles. Regional managers were expected to enforce the system while simultaneously maintaining efficiency and customer satisfaction—goals that proved mutually exclusive under the new structure. Without dedicated cross-functional support, team members improvised solutions, leading to inconsistencies and disjointed execution (Metheus Consultancy, 2023). Many locations in the St. Louis County area saw a sharp decline in drive-thru times and customer satisfaction scores.

From an ethical standpoint, the initiative demonstrated how centralized decision-making can backfire when local teams are excluded from strategic planning. The pressure to perform under unrealistic timelines fostered resentment and, in some cases, retaliation toward those who voiced concern. Frontline employees reported being reprimanded or ignored when they suggested operational improvements, undermining the company’s stated commitment to integrity and employee input (Metheus Consultancy, 2023).

Additionally, cross-cultural impacts surfaced in urban franchise locations, particularly in St. Louis City and East St. Louis. These restaurants employed large numbers of workers from marginalized communities, many of whom experienced communication gaps and felt overlooked during training efforts. Language barriers and cultural misunderstandings worsened implementation, further fragmenting teams and lowering productivity. The lack of inclusive planning and resource support amplified the challenges and highlighted systemic blind spots.

In summary, the failure of the “Made for You” initiative in the St. Louis region reflects how ineffective team design, poor leadership communication, and ethical misalignment can sabotage collaboration. Organizations that overlook frontline voices and ignore cultural context risk eroding team trust and failing to execute even well-intended innovation.

References

Metheus Consultancy. (2023, September 20). When companies overlook teamwork: Real-world failures and consequences. https://www.metheus.co/insights/when-companies-overlook-teamwork-real-world-failures-and-consequences/

Discussion Questions

- How did the lack of communication between corporate leadership, regional managers, and frontline employees contribute to the failure of the “Made for You” initiative? What strategies could have been implemented to improve communication and foster collaboration across these levels?

- The case highlights poor team design, where roles and responsibilities were unclear, and employees were left to improvise. How might clearer role definitions and better training have impacted the success of the initiative? Reflect on a time when unclear roles affected teamwork in your own experience.

- Cross-cultural misunderstandings and language barriers were significant challenges in urban franchise locations. How can organizations ensure that communication and training efforts are inclusive and culturally sensitive? What steps would you recommend to address these issues in a diverse workforce?

- Ethical concerns arose when employees felt ignored or reprimanded for providing feedback. How can organizations create a culture where employee input is valued and acted upon? Reflect on the role of psychological safety in fostering open communication and preventing ethical lapses.

Section 9.2: Group Dynamics: Understanding the Moving Parts of Teamwork

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, you should be able to do the following:

- Identify and compare the characteristics of formal and informal groups, including how group norms may evolve differently within each type.

- Describe the stages of group development (forming, storming, norming, performing, and adjourning), emphasizing how group norms are established and renegotiated throughout the group’s lifecycle.

- Recognize and analyze examples of the punctuated-equilibrium model in student, work, or community groups, and discuss how this model interacts with changing norms and group processes.

- Assess the impact of group cohesion on team performance, considering factors such as similarity, stability, size, support, and satisfaction, and how norms contribute to or hinder cohesion.

- Examine how social loafing affects group participation, and explore the role of unclear or implicit norms in enabling this phenomenon.

- Analyze the influence of collective efficacy on group outcomes, including how shared beliefs and norms affect motivation, collaboration, and goal achievement.

- Explore the formation, enforcement, and impact of group norms, including their ability to enhance group functionality or unintentionally reinforce exclusion, conformity, or inequality.

In the study of organizational communication, a group is understood as a collection of individuals whose interactions affect one another’s behaviors, perceptions, and outcomes. In most modern organizations—from retail shifts to corporate project teams—work is coordinated and accomplished through group-based efforts. How these groups function has critical implications for morale, effectiveness, and overall productivity (Jablin & Putnam, 2023).

Groups that foster cooperation, mutual respect, and shared purpose tend to operate at high performance levels. In contrast, teams marked by unresolved conflict or toxic dynamics can stall progress and demotivate members. For college students balancing employment and academics, understanding group structures can help navigate both workplace hierarchies and informal networks for support and success.

Formal Groups: Designed for Specific Goals

Formal groups are intentionally established by an organization to perform designated tasks or achieve stated objectives. Membership is often defined by job roles or titles, and communication tends to follow standardized procedures. Examples include departments, committees, or customer service teams. These groups often operate with clear protocols, goals, and performance measures (Whetsell et al., 2021). For example, consider a sophomore student working in a university dining hall. That student is part of a formal group with other employees, supervisors, and shift managers. Tasks are assigned, responsibilities clarified, and work gets evaluated—all within a formal organizational framework.

For students carrying financial aid debt, such formal groups may also serve as entry points into institutional systems where advocating for better scheduling or support policies could make a meaningful difference.

Informal Groups: Connection, Community, and Support

Informal groups emerge naturally among individuals who share interests, experiences, or emotional bonds. They are not created by the organization, but rather form organically and can significantly affect group cohesion, workplace climate, and information sharing (Joya, 2020). These groups are especially powerful in helping members feel seen and supported in stressful environments. For example, a group of commuting students working at the same retail store might meet up weekly after class to swap shift tips, vent about balancing work and school, and trade strategies for maximizing their aid dollars. This informal group provides relief, practical advice, and emotional reinforcement—often more impactful than formal resources.

Informal groups also exist within formal settings. The group chat among coworkers that helps cover unexpected shifts or share mental health memes? That’s informal—and it’s shaping workplace culture.

Why Formal and Informal Groups Matter

Both group types are vital. Formal groups create structure and enable collective achievement. Informal groups cultivate interpersonal trust and reinforce resilience, especially in environments marked by low pay, high pressure, or social isolation.

For today’s students—many of whom work multiple jobs, rely on aid, and rarely have downtime—understanding group dynamics isn’t just academic; it’s survival. Whether joining a formal workplace team or finding solidarity with classmates in a study group, the ability to navigate both spheres is a communication skill worth mastering.

Group Norms: The Unspoken Rules That Shape Team Culture

Group norms are the shared expectations, behaviors, and values that guide how members interact within a team. These norms—whether explicit or implicit—help define what is considered acceptable, respectful, and productive in a group setting (Smith, 2020). They emerge organically through interaction, observation, and socialization, and they play a critical role in shaping communication patterns, decision-making, and group identity (O’Hair & Wiemann, 2004).

For college students balancing jobs and financial aid, group norms can be both a source of stability and stress. In a study group, for example, norms might include showing up on time, contributing equally, and respecting each other’s schedules. In a work-study team, norms may involve informal expectations like covering for a coworker during exams or avoiding personal phone use during shifts. These norms often develop without formal discussion, yet they strongly influence group dynamics and individual behavior (Engleberg & Wynn, 2013).

Norms can be general, applying to all members (e.g., meeting punctuality), or role-specific, guiding behavior based on assigned responsibilities (e.g., the team leader sends out agendas). They may also be explicit, such as written ground rules, or implicit, like the unspoken agreement not to interrupt during brainstorming sessions (Brilhart & Galanes, 1998). Importantly, norms help groups avoid conflict, maintain cohesion, and reinforce shared values—especially when members come from diverse backgrounds or face external pressures like financial stress or limited time availability (Feldman, 1984).

However, norms can also become problematic when they discourage dissent, reinforce exclusion, or prioritize conformity over creativity. For instance, a group that values speed over thoroughness may unintentionally silence members who raise concerns. Recognizing and revisiting norms throughout a group’s lifecycle—especially during the norming and performing stages—can help ensure they remain inclusive, effective, and aligned with the group’s goals (Hackman, 1996).

For students, learning to identify, negotiate, and challenge group norms is a vital communication skill. It empowers them to advocate for fairness, foster collaboration, and build teams that support both academic success and personal well-being.

Stages of Group Development

Forming, Storming, Norming, and Performing

American organizational psychologist Bruce Tuckman introduced a foundational model of group development in 1965, identifying four key stages—forming, storming, norming, and performing—that teams typically experience as they evolve (Tuckman, 1965). Later, in collaboration with Mary Ann Jensen, he added a fifth stage, adjourning, to account for the conclusion of group work and the emotional and logistical transitions that follow (Tuckman & Jensen, 1977). Much like individuals progress through life stages, groups undergo a developmental journey that shapes their communication, cohesion, and productivity.

In the forming stage, group members are introduced and begin to orient themselves to the task and each other. This phase is often marked by politeness, uncertainty, and a desire to be accepted. For college students juggling multiple jobs and financial aid obligations, forming might involve negotiating meeting times around work shifts or clarifying expectations for shared responsibilities in a group project. Leaders at this stage tend to be more directive, helping establish structure and purpose (Bonebright, 2010).

The storming stage follows, characterized by conflict, competition, and the surfacing of differing opinions. This phase is essential for growth, though it can be uncomfortable. Students may clash over workload distribution, especially if some members are perceived as less available due to outside commitments. If unresolved, these tensions can resurface later in the group’s lifecycle. Effective facilitation during storming involves coaching behaviors—encouraging open dialogue, managing conflict, and fostering mutual respect (Kennedy, 2020).

Once the group navigates storming, it enters the norming stage, where members establish shared norms, roles, and expectations. Trust begins to build, and collaboration becomes more fluid. For students, this might mean agreeing on communication platforms (e.g., Slack or Google Docs), setting realistic deadlines, and recognizing each other’s strengths. Groups that invest time in social bonding during forming tend to handle norming more smoothly, as interpersonal understanding enhances resilience (Stein, 2023).

In the performing stage, the group operates at a high level of effectiveness. Members are autonomous, interdependent, and focused on achieving collective goals. For a student team, this could mean efficiently completing a research presentation while balancing work shifts and academic deadlines. Leadership becomes more delegative, with members taking initiative and solving problems collaboratively (WCU of PA, n.d.).

Finally, the adjourning stage involves wrapping up tasks and disbanding the group. This phase can evoke mixed emotions—relief, pride, or even sadness. Students may reflect on what they’ve learned, celebrate their accomplishments, and prepare for future collaborations. Recognizing this stage helps normalize transitions and encourages closure (Tuckman & Jensen, 1977).

While not all groups follow this model linearly, Tuckman’s framework remains a valuable tool for understanding team dynamics and guiding communication strategies in both academic and professional settings.

Figure 9.2 Stages of the Group Development Model

Storming -> Norming -> Performing -> Adjourning” width=”500″>

Storming -> Norming -> Performing -> Adjourning” width=”500″>

Forming

The forming stage marks the beginning of a group’s development, when members come together—sometimes as strangers, sometimes with prior connections—and begin to orient themselves to the group’s purpose and each other. This phase is typically characterized by politeness, caution, and a desire to be accepted, as individuals grapple with uncertainty about roles, expectations, and power dynamics (Tuckman, 1965; Stein, 2023). Questions like “Will I be accepted?” or “Who’s in charge?” often linger beneath the surface. Members tend to avoid conflict, observe group norms, and engage in abstract discussions about the task at hand, which can frustrate those eager to dive into action (Bonebright, 2010).

For college students juggling multiple jobs and financial aid obligations, the forming stage may involve negotiating meeting times around work shifts, clarifying expectations for shared responsibilities, and finding common ground—such as shared academic pressures or commuting challenges. This early bonding can be crucial. Research suggests that groups who invest time in social connection during forming are better equipped to handle future challenges (Kennedy, 2020). Members may also test leadership boundaries, either by observing an appointed leader or watching to see if someone naturally emerges. During this phase, students may feel a mix of pride at being selected for a team and anxiety about whether they can contribute meaningfully given their external commitments. Establishing trust, defining acceptable behaviors, and exploring how tasks will be divided are key outcomes of this stage, which typically lasts only a few meetings before deeper dynamics begin to surface.

Storming

The storming stage is the second phase of group development, marked by rising tensions, emerging conflicts, and the surfacing of individual identities. Once members feel safe enough to shed social facades, they begin asserting themselves more authentically—often leading to disagreements over goals, roles, and processes (Tuckman, 1965; Stein, 2023). This phase is characterized by defensiveness, competition, and emotional volatility, as participants explore questions like “Can I be myself, have influence, and still be accepted?” (Bonebright, 2010). Power struggles may emerge, cliques can form, and resistance to leadership is common. For example, a student group working on a class presentation might clash over who should lead, how to divide tasks, or whether deadlines are realistic—especially when some members are juggling jobs and financial aid obligations that limit their availability. These tensions, while uncomfortable, are a natural part of group evolution and can unlock creative energy if managed constructively (Kennedy, 2020).

Although productivity may stall during storming, the group is laying the groundwork for deeper collaboration. Members begin to express their true thoughts and feelings, which—if supported by active listening and conflict resolution—can lead to stronger trust and more effective teamwork. For students, this might mean negotiating workload expectations, acknowledging external pressures, and finding ways to support one another through shared challenges. Groups that fail to navigate this stage often remain stuck, but those that embrace it as a growth opportunity are better positioned to move into norming and beyond.

Workplace Strategy Pack

Avoiding the Storming Phase in Group Development

Objective: To empower employees with proactive communication and collaboration strategies that prevent teams from stagnating in the Storming Phase of Tuckman’s group development model.

Understanding the Storming Phase

The Storming Phase is marked by interpersonal conflict, power struggles, and resistance to group norms. If unresolved, it can derail productivity and morale.

“Groups that remain in the storming stage are unlikely to succeed in completing their tasks or achieving their purpose.” — Whatcom Community College (n.d.)

Why Groups Get Stuck

- Lack of trust or psychological safety

- Poor role clarity or ambiguous goals

- Ineffective conflict resolution mechanisms

- Absence of shared norms or values

- Leadership vacuum or micromanagement

Strategy Toolkit

1. Establish Clear Norms Early

- Co-create team agreements on communication, decision-making, and accountability.

- Use kickoff meetings to define expectations and working styles.

2. Foster Open Dialogue

- Encourage respectful disagreement and active listening.

- Use structured formats like “round-robin” sharing or anonymous feedback tools.

3. Clarify Roles and Goals

- Use RACI charts (Responsible, Accountable, Consulted, Informed) to define responsibilities.

- Align individual tasks with team objectives.

4. Build Psychological Safety

- Normalize vulnerability and mistakes as part of growth.

- Leaders should model humility and openness.

5. Practice Adaptive Leadership

- Shift from directive to coaching styles as the team matures (Tuckman, 1965).

- Intervene early when conflict arises, but avoid over-controlling.

6. Use Team-Building Interventions

- Schedule regular check-ins and retrospectives.

- Incorporate personality assessments (e.g., MBTI, DISC) to understand dynamics.

Empowerment Tip

“Interstage awareness and proactive leadership can minimize the destructive effects of the storming phase.” — Lail (2021)

References

Bonebright, D. A. (2010). 40 years of storming: A historical review of Tuckman’s model of small group development. Human Resource Development International, 13(1), 111–120. https://doi.org/10.1080/13678861003589099Lail, J. (2021). Between forming and storming: Interstage awareness in group formation. Journal of Educational Leadership, 23(1). https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED614298.pdf

Tuckman, B. W. (1965). Developmental sequence in small groups. Psychological Bulletin, 63(6), 384–399. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0022100

Whatcom Community College. (n.d.). 2.2 Group Formation – Organizational Communication Anthology. https://textbooks.whatcom.edu/cmst245/chapter/2-2/

Once group members discover that they can be authentic and that the group is capable of handling differences without dissolving, they are ready to enter the next stage, norming.

Norming

The norming stage of group development is often met with a collective sense of relief and renewed energy. Having weathered the interpersonal tensions of storming, group members begin to feel more cohesive, cooperative, and committed to the team’s goals (Tuckman, 1965; Stein, 2023). This phase is marked by the emergence of shared norms—unwritten rules and expectations that guide behavior and communication. Members establish operating procedures, clarify roles, and begin making decisions more efficiently, with larger choices handled collectively and smaller tasks delegated to individuals or subgroups (Bonebright, 2010).

For college students juggling jobs and financial aid obligations, norming might involve agreeing on realistic deadlines that accommodate work shifts, choosing communication platforms that fit everyone’s schedules, and developing mutual respect for each other’s time constraints. Students may begin to ask for help more openly, offer constructive feedback, and even form friendships that extend beyond the project. This emotional openness and trust are key indicators of successful norming, as members shift from guarded interactions to genuine collaboration (Kennedy, 2020).

At this stage, the group leader transitions from a directive role to that of a facilitator, empowering members to take ownership of their work and interpersonal dynamics. With morale high and productivity increasing, this is an ideal time to host a team-building activity or informal social gathering—especially for students who rarely get downtime. Such events can reinforce cohesion and help sustain momentum as the group moves toward performing.

Performing

The performing stage represents the pinnacle of group development, where members operate with high levels of autonomy, competence, and mutual respect. Energized by a shared vision and a sense of unity, the group becomes more interdependent, embracing individual differences while functioning as a cohesive whole (Tuckman, 1965; Stein, 2023). At this point, members are not only focused on completing tasks but also critically evaluating how they work together. They ask reflective questions such as, “Are our procedures supporting productivity?” or “Do we have effective strategies for managing conflict before it escalates?” This introspection signals a mature group dynamic, where communication is intentional and aligned with collective goals (Bonebright, 2010).

For college students managing multiple jobs and financial aid obligations, the performing stage might involve coordinating a complex group presentation while navigating tight schedules and limited resources. Members take initiative, support one another, and adapt fluidly to challenges. Leadership becomes more of a coaching role, guiding skill development and encouraging peer-led problem solving (Kennedy, 2020). Students may also begin to reflect on their personal growth, asking how they can become more effective communicators, collaborators, and leaders. This stage is not guaranteed for all groups, but when achieved, it reflects a high-functioning team capable of producing quality outcomes and sustaining momentum.

Adjourning

The adjourning stage marks the final phase of group development, when a team disbands after completing its goals or due to external changes such as organizational restructuring (Tuckman & Jensen, 1977). Like graduating from college or leaving a familiar job, this transition can evoke mixed emotions—pride in accomplishments, sadness over parting ways, and uncertainty about what comes next. For students who thrive on routine and have built strong bonds with teammates, the ending of a group project or campus organization can feel especially bittersweet. Research suggests that acknowledging these emotions and providing closure is essential for individual and collective growth (Bonebright, 2010; Upwork Team, 2024).

In academic and workplace settings, groups often form around temporary projects. For example, a student-led financial literacy campaign or a semester-long research team may dissolve once the final deliverable is submitted. Students juggling jobs and financial aid may feel relief at reclaiming time, but also miss the camaraderie and shared purpose. Leaders and members alike should approach this stage with compassion and intentionality. Debriefing sessions—where participants reflect on lessons learned, celebrate achievements, and express appreciation—can help ease the transition and reinforce a sense of accomplishment (Planio, 2025; Project Arrive, 2024).

Celebratory rituals such as group dinners, thank-you notes, or informal meetups can also foster closure and honor the group’s journey. These practices not only validate individual contributions but also prepare members to carry forward insights and relationships into future endeavors. When done thoughtfully, adjourning becomes more than an ending—it becomes a launchpad for continued growth.

From Punctuated Equilibrium to Group Decision-Making

The Punctuated-Equilibrium Model

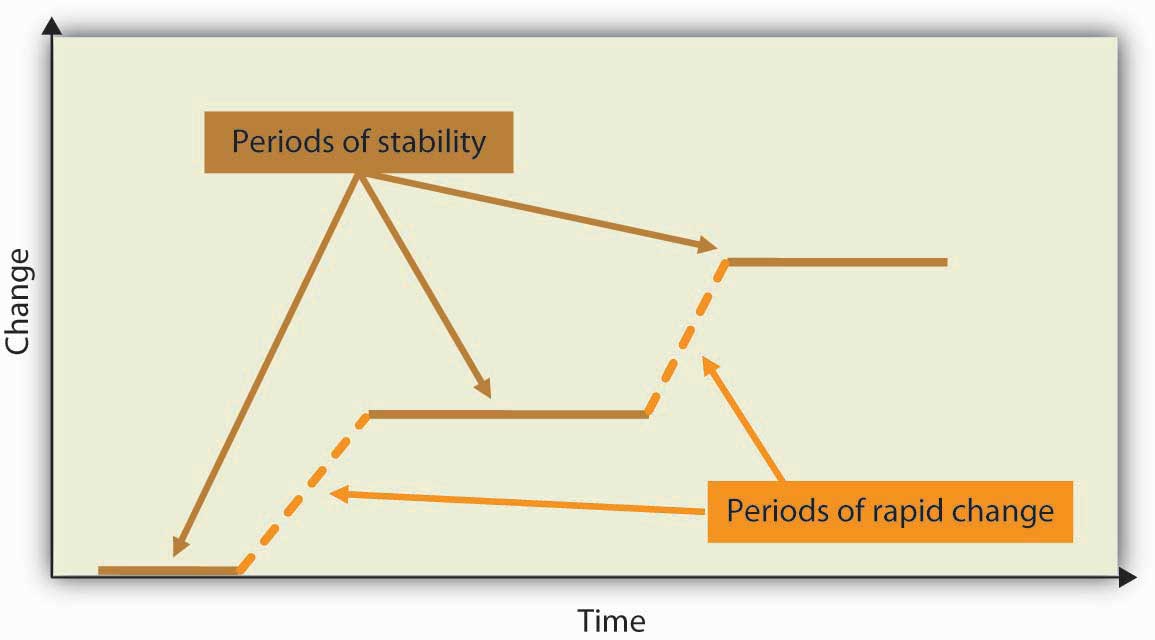

The Punctuated Equilibrium Model (PEM) describes group development as alternating periods of stability and rapid change, often triggered by deadlines or external pressures (Gersick, 1988). While PEM is useful for understanding temporary teams, it lacks guidance on how decisions are made and why some groups outperform others in dynamic environments.

Recent organizational communication research recommends replacing PEM with a Group Decision-Making Process (GDMP)—a structured, inclusive framework that emphasizes communication, collaboration, and critical thinking (Yang, Jiang, & Cheng, 2025). This model is especially relevant for student teams, interdisciplinary workgroups, and collaborative organizations.

Core Stages of the Group Decision-Making Process

- Problem Identification – Define the issue and ensure shared understanding.

- Information Gathering – Collect relevant data and stakeholder input.

- Generating Alternatives – Use brainstorming or structured techniques like the Delphi method.

- Evaluating Alternatives – Compare options based on feasibility, ethics, and impact.

- Choosing the Best Option – Reach consensus or use structured voting.

- Implementation – Assign roles and execute the decision.

- Review and Feedback – Reflect on outcomes and refine future decisions.

This process supports continuous engagement, reduces misunderstandings, and encourages cognitive diversity—key factors in avoiding groupthink and improving decision quality (APA, 2025; SpringerLink, 2025).

Cohesion

The concept of cohesion refers to the emotional and psychological bonds that unite group members—a kind of social glue that transforms individuals into a collective (Forsyth, 2021; Beal et al., 2003). In cohesive groups, members share a sense of identity, purpose, and mutual support, often communicating in structured and effective ways. This unity fosters collaboration and enhances both group performance and individual satisfaction (Evans & Dion, 1991).

For college students balancing coursework, jobs, and financial aid, cohesion can be a lifeline. Whether in study groups, campus organizations, or work teams, cohesive environments offer emotional support, accountability, and a shared commitment to goals. Students in cohesive groups are more likely to attend meetings, contribute meaningfully, and persevere through academic or personal challenges. These groups often become safe spaces where members feel seen, valued, and empowered.

Several key factors influence group cohesion:

- Similarity: Shared backgrounds, values, or goals—such as being first-generation students or working part-time—can strengthen bonds (Drew, 2025).

- Stability: Groups that meet consistently over time tend to develop deeper trust and unity.

- Size: Smaller groups allow for more intimate interactions and stronger interpersonal connections.

- Support: Encouragement, coaching, and peer mentoring reinforce group identity and morale.

- Satisfaction: When members feel respected and appreciated, cohesion flourishes.

The benefits of cohesion extend beyond productivity. Students in cohesive groups often report higher self-esteem, lower stress levels, and greater resilience (Lumina Foundation, 2025). For example, on-campus work-study teams that include professional development and supervisor feedback foster not only job skills but also a sense of belonging and purpose (Forward Pathway, 2025; Inside Higher Ed, 2025). These environments can buffer against the pressures of financial insecurity and academic overload, helping students thrive both socially and academically.

Workplace Strategy Pack

Creating and Maintaining a Cohesive Team

Objective: To equip managers with actionable strategies grounded in organizational communication and psychology to build and sustain team cohesion, trust, and performance.

Why Team Cohesion Matters

Cohesive teams are more productive, resilient, and innovative. They exhibit stronger interpersonal trust, faster conflict resolution, and higher engagement. According to Forsyth (2021), cohesion is a critical ingredient that transforms ordinary groups into high-performing collectives.

“Cohesion enhances motivation, which improves performance—but improvements in performance also increase cohesion.” — Forsyth (2021)

Strategy Toolkit for Managers

1. Define a Clear Purpose and Shared Goals

- Align team members around a compelling mission.

- Use inclusive language (“we,” “our”) to foster group identity.

- Revisit goals regularly to reinforce commitment.

2. Foster Open and Inclusive Communication

- Encourage psychological safety by modeling vulnerability and openness (Lencioni, 2002).

- Use structured feedback loops and active listening techniques.

- Address siloed thinking by promoting cross-functional dialogue.

3. Build Trust Through Consistency and Transparency

- Share personal histories and values to deepen interpersonal bonds.

- Recognize contributions publicly and fairly.

- Avoid micromanagement—empower autonomy with accountability.

4. Invest in Team Development Interventions (TDIs)

- Implement team-building exercises, leadership coaching, and debriefing sessions (Lacerenza et al., 2018).

- Use personality assessments to understand team dynamics.

- Schedule regular retrospectives to reflect and recalibrate.

5. Encourage Diversity and Inclusion

- Validate different viewpoints and foster constructive dissent.

- Use data-driven decision-making to depersonalize conflict.

- Promote equity in participation and recognition.

6. Maintain Momentum with Rituals and Recognition

- Celebrate milestones and small wins.

- Create rituals that reinforce team identity (e.g., weekly check-ins, shared symbols).

- Use storytelling to reinforce values and purpose.

Empowerment Tip

“Team cohesion is not a one-time achievement—it’s a dynamic process that requires ongoing attention to communication, trust, and shared identity.” — Lacerenza et al. (2018)

References

Forsyth, D. R. (2021). Recent advances in the study of group cohesion. Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice, 25(3), 213–228. https://doi.org/10.1037/gdn0000163

Lacerenza, C. N., Marlow, S. L., Tannenbaum, S. I., & Salas, E. (2018). Team development interventions: Evidence-based approaches for improving teamwork. American Psychologist, 73(4), 517–531. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000295

Capability Group. (2020, December 2). How to build cohesive teams [Video]. YouTube. Watch the tutorial

Andrews, S. (2023, July 12). Nine steps to building team cohesion and a healthy work environment. Forbes Coaches Council. Read the article

Lencioni, P. (2002). The five dysfunctions of a team: A leadership fable. Jossey-Bass.

Can a Group Have Too Much Cohesion?

While cohesion is often celebrated for its benefits, too much of it can backfire. When group members prioritize belonging over critical thinking, they may suppress dissent, avoid conflict, and conform to group norms—even when those norms are counterproductive (Janis, 1972). This pressure to maintain harmony can lead to groupthink, a phenomenon where the desire for consensus overrides realistic appraisal of alternatives, reducing mental efficiency, moral judgment, and reality testing.

A contemporary example of groupthink can be seen in the persistent belief among public university boards and senior administrators that offering high executive salaries is the only way to attract top talent. This assumption often goes unchallenged, despite growing evidence that such compensation practices may conflict with the public mission of higher education. According to Boyd and Tiede (2023), collaborative decision-making around salary policy is frequently undermined by internal pressures to conform to market-driven norms, even when those norms exacerbate budgetary strain and tuition increases. The belief that university presidents must earn significantly more than faculty—sometimes ten to twenty times as much—is rarely questioned within administrative circles, even though it contradicts the values of equity and stewardship that public institutions are meant to uphold.

This dynamic reflects classic groupthink symptoms: the illusion of unanimity, suppression of dissent, and rationalization of flawed assumptions (Janis, 1972). Faculty and student voices advocating for salary equity and tuition restraint are often marginalized, while governing boards reinforce a narrow definition of leadership that equates compensation with competence. As Kelman et al. (2014) note, decision-making in bureaucratic environments tends to favor decisiveness over vigilance, which can lead to the entrenchment of problematic policies.

For college students, groupthink can show up in subtle but impactful ways. In a tightly knit study group, for example, members might avoid challenging flawed ideas to preserve social bonds. Or in a campus organization, students may hesitate to speak out against problematic practices for fear of being ostracized. This self-censorship creates a superficial sense of unity while stifling innovation and accountability.

Highly cohesive groups may also become insular, viewing outsiders as inferior or threatening. This mindset can block valuable external input and reinforce biased decision-making. For students juggling work and financial aid, such environments can be especially harmful—limiting access to diverse perspectives and discouraging advocacy for change.

Even in milder forms, excessive cohesion can derail productivity. Groups may prioritize socializing over task completion, or drift from institutional goals. For instance, a student club might focus more on bonding than fulfilling its mission, or tease high-achieving members who challenge the group’s laid-back culture.

Social Loafing

Social loafing is the tendency for individuals to exert less effort when working in a group than when working alone—a phenomenon first observed by Max Ringelmann in 1913 during rope-pulling experiments (Karau & Williams, 1993). As group size increases, individual accountability often decreases, leading to diminished motivation and performance. This effect, known as the Ringelmann effect, has been replicated across cultures and tasks (Gabrenya, Latane, & Wang, 1983; Ziller, 1957).

For college students juggling academics, jobs, and financial aid, social loafing can emerge in group projects, campus organizations, or work-study teams. A student might think, “My effort won’t make a difference,” or “Others aren’t contributing, so why should I?” These rationalizations reflect a broader perception that rewards and blame are diffused in group settings (Harkins & Petty, 1982; Taylor & Faust, 1952). The result is often uneven participation, frustration among high-performing members, and reduced overall group effectiveness.

Importantly, social loafing is not simply laziness—it’s a response to perceived inequity and lack of recognition. Research shows that fairness and transparency in group dynamics can reduce loafing behavior (Price, Harrison, & Gavin, 2006). For example, when students feel their contributions are valued and their peers are equally committed, they’re more likely to stay engaged. This is especially relevant for students working part-time or managing financial stress, who may be more sensitive to time investment and group efficiency.

To counteract social loafing, instructors and team leaders can:

- Assign clear individual roles and responsibilities.

- Use peer evaluations to increase accountability.

- Foster group cohesion through team-building and shared goals.

- Emphasize the importance of each member’s contribution to the final outcome.

These strategies help ensure that group work remains equitable, productive, and rewarding for all members—especially those balancing multiple commitments.

Workplace Strategy Pack

Addressing Uneven Contribution in Group Work

Objective: To equip employees with communication strategies and leadership tools to constructively address group members who are under-contributing, while preserving team cohesion and psychological safety.

Why It Matters

Group work thrives on shared responsibility, but when one member consistently underperforms, it can lead to resentment, reduced morale, and compromised outcomes. Research shows that clear communication, role clarity, and psychological safety are essential for resolving contribution imbalances (Edmondson & Besieux, 2021; Cai et al., 2018).

“Voice and silence in workplace conversations shape the quality of collaboration and the ability to address performance issues.” — Edmondson & Besieux (2021)

Strategy Toolkit

1. Initiate a Constructive Conversation

- Use “I” statements to express concern: “I’ve noticed some tasks haven’t been completed, and I’m worried about our timeline.”

- Avoid blame; focus on shared goals and outcomes.

2. Clarify Roles and Expectations

- Revisit the group’s task list and assign clear responsibilities.

- Use collaborative tools (e.g., shared documents, task boards) to track progress transparently.

3. Explore Underlying Causes

- Ask open-ended questions: “Is there anything preventing you from contributing fully?”

- Consider personal stressors, unclear expectations, or skill mismatches.

4. Rebuild Accountability

- Set short-term goals and check-in points.

- Encourage peer feedback and mutual support.

- If needed, escalate to a supervisor or team lead with documentation.

5. Foster Psychological Safety

- Create a space where team members feel safe to speak up.

- Reinforce that feedback is about improvement, not punishment.

Empowerment Tip

“Empowering leadership enhances person-group fit, which increases engagement and accountability.” — Cai et al. (2018)

References

Cai, D., Cai, Y., Sun, Y., & Ma, J. (2018). Linking empowering leadership and employee work engagement: The effects of person-job fit, person-group fit, and proactive personality. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, Article 1304. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01304

Edmondson, A. C., & Besieux, T. (2021). Reflections: Voice and silence in workplace conversations. Journal of Change Management, 21(3), 269–286. https://doi.org/10.1080/14697017.2021.1928910

Skills for Change. (2023). How to deal with a team member who is not contributing. https://skillsforchange.com/how-to-deal-with-a-team-member-who-is-not-contributing/

Collective Efficacy

Collective efficacy refers to a group’s shared belief in its ability to organize and execute actions required to achieve success (Bandura, 1997). This perception is shaped by several factors, including observing successful peer groups (“If they did it, we can too”), verbal encouragement (“We’ve got this”), and emotional climate (“This team feels right”). When students feel confident in their group’s capabilities, they’re more likely to collaborate effectively, persist through challenges, and achieve stronger outcomes (Gully et al., 2002; Porter, 2005; Tasa, Taggar, & Seijts, 2007).

For college students juggling coursework, jobs, and financial aid, collective efficacy can be a game-changer. In high-interdependence settings—such as group research projects, student-led campaigns, or work-study teams—each member’s success is tightly linked to others’ contributions. When students trust their peers and believe in the group’s potential, they’re more likely to stay engaged, share resources, and support one another.

Research shows that collective efficacy is especially powerful when task interdependence is high (Gully et al., 2002). For example, in a student-run tutoring program, tutors rely on each other to maintain consistent quality and scheduling. If one person falters, the whole system feels it. But when the team believes in its shared ability to succeed, performance improves across the board.

To build collective efficacy in student groups:

- Celebrate small wins to reinforce shared success.

- Encourage open communication and mutual support.

- Use peer modeling—highlighting successful teams as inspiration.

- Foster emotional safety so students feel valued and heard.

These strategies help students develop not only confidence in their group’s abilities but also a deeper sense of belonging and purpose.

Insider Edge

Empowering the Unheard in Overly Cohesive Teams

Objective: To equip employees with strategies to assert their voice and influence in teams where excessive cohesion may suppress dissent, innovation, or individual expression.

The Hidden Risk of Too Much Cohesion

While cohesion is often celebrated, excessive cohesion can lead to:

- Groupthink and conformity pressure

- Suppression of dissenting voices

- Resistance to change or innovation

- Over-identification with group norms at the expense of individual insight

“Cohesion enhances performance, but when it becomes too strong, it may stifle critical thinking and marginalize minority perspectives.” — Forsyth (2021)

Strategy Toolkit for the Unheard

1. Reframe Silence as a Signal

- Recognize that feeling unheard may indicate group over-conformity, not personal inadequacy.

- Use this awareness to reframe your role as a constructive challenger.

2. Use Strategic Voice Techniques

- Frame dissent as a contribution to group success: “I’d like to offer a different angle that might strengthen our approach.”

- Use data or examples to support your point and reduce emotional resistance.

3. Build Alliances

- Find allies who share your concerns and speak collectively.

- Use informal conversations to test ideas before raising them in group settings.

4. Engage in Meta-Communication

- Suggest a team reflection on communication norms: “Can we check in on how we’re making space for different perspectives?”

- Encourage rotating facilitation or anonymous feedback tools.

5. Leverage Organizational Channels

- Use skip-level meetings, employee resource groups, or feedback platforms to raise concerns.

- Document patterns of exclusion if needed for escalation.

Empowerment Tip

“Empowering employees to speak up requires a culture that values choice and autonomy.” — Detert & Burris (2021)

References

Detert, J. R., & Burris, E. R. (2021, October). Research: What makes employees feel empowered to speak up? Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2021/10/research-what-makes-employees-feel-empowered-to-speak-up

Forsyth, D. R. (2021). Recent advances in the study of group cohesion. Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice, 25(3), 213–228. https://doi.org/10.1037/gdn0000163

Espinoza Morán, H., Artiaga Bolaños, A. V., & Castro Guevara, J. (2022). Group cohesion and its relationship with organizational communication. Sapienza: International Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies, 3(2). https://journals.sapienzaeditorial.com/index.php/SIJIS/article/view/316

Carter, E. (2020). The impact of communication strategies on employee engagement: A comprehensive review. Academy of Organizational Communication Studies. https://www.abacademies.org/articles/the-impact-of-communication-strategies-on-employee-engagement-a-comprehensive-review.pdf

Discussion Questions

- Reflect on the most cohesive group you’ve ever been part of. How did that group establish and maintain shared norms related to similarity, stability, size, support, and satisfaction? Were these norms explicit or implicit?

- Why do you think social loafing occurs, especially in groups where norms aren’t clearly defined? Can implicit norms contribute to unequal participation?

- What communication strategies or norm-setting practices can help reduce social loafing in a group? How can general and role-specific norms promote accountability and engagement?

- Think of a time when collective efficacy either helped or hurt a team’s performance. What role did group norms and shared expectations play in that outcome?

- Have you encountered group norms that discouraged dissent or limited creativity? How would you recommend revisiting or renegotiating norms to make them more inclusive and effective?

Section 9.3: Blueprint for Collaboration: Key Features of Team Design

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, you should be able to do the following:

- Differentiate between groups and teams by examining structural, functional, and communicative distinctions.

- Explain the rise of team-based collaboration through organizational, technological, and social trends influencing modern work and academic environments.

- Describe core team roles and responsibilities—including task, social, and boundary-spanning roles—and how they contribute to team effectiveness.

- Identify key types of teams (e.g., functional, cross-functional, virtual) and assess how their structure impacts communication, coordination, and adaptability.

- Evaluate team design considerations, including optimal composition, size, diversity, and leadership autonomy, using current organizational communication research.

- Analyze how teams develop over time, applying models such as Tuckman’s stages and the punctuated-equilibrium model to understand shifts in norms and communication practices.

- Assess the role of psychological safety and trust in fostering innovation, learning, and constructive conflict resolution.

- Interpret collective efficacy and its influence on team performance, motivation, and resilience.

- Distinguish between task and relational conflict, examining their effects on team outcomes and strategies for managing each constructively.

- Apply feedback and recognition practices to reinforce accountability, engagement, and team learning in diverse communication settings.

Designing Teams That Work: From Structure to Strategy

Whether you’re launching a group project, leading a campus organization, or entering the workforce, understanding how teams are built—and how they actually function—is essential. Effective teams don’t just happen; they’re carefully designed with purpose, structure, and clear communication in mind.

This section unpacks the essential components of team design, from the differences between informal groups and goal-driven teams, to the roles members play, the tasks they tackle, and the diverse individuals who shape team outcomes. Drawing from organizational communication research, we’ll explore how decisions about team size, member diversity, leadership styles, and role assignments directly influence group cohesion, creativity, and success.

Whether you’re building a team from scratch or stepping into one already formed, these insights will help you recognize what makes a team thrive—and what holds it back.

From Groups to Teams: Foundational Differences

n organizational settings—whether academic, professional, or community-based—people often work in groups. However, not all groups function as teams. A group is simply a collection of individuals who may share a space or task but operate independently, with minimal coordination or shared accountability (Keyton, 2017). Groups can be formal, such as a department or committee, or informal, like coworkers who socialize during breaks. While groups may contribute to organizational outcomes, their performance is often limited by “process losses”—inefficiencies caused by poor coordination, unclear roles, or lack of shared purpose (Stewart, 2010).

A team, by contrast, is a structured and interdependent unit of individuals working collaboratively toward a shared goal. Teams are defined by mutual accountability, complementary skills, and intentional communication practices (Katzenbach & Smith, 1993). For example, a student project team that divides tasks, sets deadlines, and supports each other’s learning is more likely to succeed than a group of students working in isolation. Effective teams rely on clear norms, trust, and shared expectations to navigate challenges and maintain cohesion (Cannon-Bowers & Salas, 2001).

The rise of team-based structures in organizations reflects the growing complexity of tasks and the need for diverse perspectives. Advances in technology, globalization, and remote work have made collaboration across roles and locations more critical than ever (Keyton, 2017). Research shows that when team members perceive their outcomes as interdependent, they communicate more effectively and perform better (De Dreu, 2007). This is especially relevant for working-class college students who often juggle jobs, coursework, and collaborative assignments—making team skills essential for both academic and workplace success.

However, teams are not a universal solution. Organizations and individuals should assess whether a task requires diverse skills, shared decision-making, and coordinated effort before forming a team (Rees, 1997). When these conditions are met, well-designed teams can outperform individuals and traditional groups, delivering both measurable results and personal growth opportunities.

Understanding Team Purpose

Teams exist to accomplish tasks that are often too complex, creative, or interdependent for individuals to tackle alone. Richard Hackman (1976) identified three primary categories of team tasks: production, idea generation, and problem solving. Production tasks involve creating tangible outputs, such as a marketing plan, product prototype, or event schedule. Idea-generation tasks focus on creativity and innovation, such as brainstorming new strategies or designing a process improvement. Problem-solving tasks require teams to analyze situations, make decisions, and develop actionable plans. Many real-world teams—especially in academic and workplace settings—engage in all three types at different stages of a project.

For college students balancing coursework, jobs, and financial stress, understanding a team’s purpose helps clarify expectations and improve collaboration. For example, a student-led campaign to improve campus food access may begin with idea generation (brainstorming solutions), shift into production (creating flyers and outreach materials), and end with problem solving (adjusting strategies based on feedback). Recognizing these task types helps students align their efforts with the team’s evolving goals.

Equally important is the concept of task interdependence, which refers to how much team members rely on one another to complete their work. Research shows that self-managing teams perform best when tasks are highly interdependent—meaning members must share information, coordinate actions, and support each other to succeed (Langfred, 2005; Liden, Wayne, & Bradway, 1997). There are three main types of task interdependence:

- Pooled interdependence: Members work independently and combine their outputs. For example, students each write separate sections of a paper and compile them at the end.

- Sequential interdependence: One member’s output becomes another’s input. A student writes the introduction, another builds on it with findings, and a third writes the conclusion.

- Reciprocal interdependence: Members collaborate throughout each phase, continuously sharing ideas and refining the work together.

In addition, outcome interdependence refers to how rewards or evaluations are shared. When students know their grade or recognition depends on the team’s overall performance, they’re more likely to stay engaged and support one another.

Understanding team purpose and interdependence helps students navigate group work more effectively—whether in a classroom, workplace, or community setting. It also lays the foundation for stronger communication, accountability, and shared success.

Types of Teams in Organizations

Organizations rely on diverse team structures to address goals, solve problems, and foster innovation. For college students entering academic and professional environments, recognizing how team structures function is essential. One-third of all teams in the U.S. are temporary, often assembled as task forces to address a specific issue until resolution (Gordon, 1992). Other teams, such as product development teams, may span short-term or long-term timelines depending on the nature of their assignments. In matrix organizations, individuals from various departments collaborate in cross-functional teams, allowing a range of expertise to shape project outcomes. This setup reflects many college group projects, where students contribute different strengths such as design, writing, or data analysis.

The rise of virtual teams has transformed collaboration. These teams operate across physical boundaries, connecting members from different cities, states, or even countries. Companies often form virtual teams to access specialized talent or streamline operations globally (Ahuja & Galvin, 2003). For instance, BakBone Software employed a 13-member technical support team spanning offices in California, Maryland, England, and Tokyo, enabling broader hiring and stronger candidate selection due to geographic diversity (Alexander, 2000). However, managing virtual teams presents unique challenges, such as the difficulty in overseeing work directly. Organizations must rely on evaluation systems focused on deliverables rather than visibility, ensuring that team members produce measurable results. Building trust among team members becomes critical and often involves bringing teams together in person at least once (Kirkman et al., 2002). Communication tools like video conferencing, shared documents, and wikis facilitate interaction, yet disengagement and conflict avoidance can undermine team effectiveness (Montoya-Weiss, Massey, & Song, 2001).

In modern organizations, empowered teams and self-managed teams are increasingly favored for their ability to take ownership of goals and processes. These teams demonstrate higher performance when autonomy and accountability are clearly established (Mathieu, Gilson, & Ruddy, 2006). Similarly, in student-led initiatives, decision-making and distributed leadership often mirror empowered team dynamics—especially in clubs or project-based learning environments.

At the highest level of decision-making, top management teams (TMTs) help guide an organization’s strategy and culture. Selected by the chief executive officer (CEO), these teams often include roles like chief operating officer (COO), chief financial officer (CFO), chief marketing officer (CMO), and chief technology officer (CTO). Their decisions—ranging from new market expansion to acquisitions—shape the company’s priorities and behavior throughout all levels (Carpenter, Geletkanycz, & Sanders, 2004). Importantly, diverse TMTs are more effective, both functionally and demographically. Leadership expert Jim Collins emphasized that exceptional organizations prioritize team composition before strategy, “getting the right people on the bus” and positioning them properly before choosing a direction (Collins, 2001). Just as student organizations benefit from deliberate role assignment and succession planning, companies also invest in identifying future leaders to sustain high performance over time.

Understanding the structures and dynamics of different teams prepares students for collaboration in real-world settings, equipping them to contribute meaningfully across disciplines and adapt to evolving professional environments.

Designing Teams for Success

Creating effective teams requires more than assembling talented individuals—it demands thoughtful design rooted in communication, coordination, and shared purpose. Organizational communication research highlights four key dimensions that shape team success: composition, size, diversity, and leadership autonomy.

Team composition refers to the mix of skills, personalities, and experiences that members bring to the table. A well-composed team balances technical expertise with interpersonal strengths, ensuring that members complement rather than duplicate one another (Allen & O’Neill, 2015). Research shows that personality traits—especially conscientiousness, openness, and agreeableness—predict both individual and team performance (Prewett et al., 2018; Costa & McCrae, 1992). For college students, this means selecting teammates who not only know the material but also communicate clearly, follow through on commitments, and adapt to challenges.

Team size plays a critical role in coordination and productivity. While larger teams offer broader expertise, they also increase communication overhead and risk social loafing (Mao et al., 2016). Studies suggest that smaller teams—typically between 4 and 7 members—perform better on complex tasks requiring high interdependence and active participation (Bumbuc, 2024; Mathieu et al., 2019). For student projects, keeping teams lean can improve engagement, accountability, and decision-making speed.

Team diversity—including cognitive, demographic, and functional differences—can enhance creativity, problem-solving, and innovation. Diverse teams bring varied perspectives that challenge assumptions and expand idea generation (Edmans, 2025; Gibbs et al., 2019). However, diversity also introduces challenges: reduced cohesion, communication barriers, and potential conflict (Budovitch, 2016; Reagans & Zuckerman, 2001). To harness diversity’s benefits, teams must establish inclusive norms, psychological safety, and shared goals (van Knippenberg et al., 2004).

Team leadership autonomy refers to how leadership is distributed within the team. Traditional manager-led teams rely on a single leader for direction, while self-managed and shared leadership models empower members to take initiative and share responsibilities (Carson et al., 2007; Klasmeier et al., 2025). Research shows that shared leadership improves team resilience, satisfaction, and performance—especially when supported by trust and clear communication (Edelmann et al., 2020; Badura & Crews, 2025). For students, rotating leadership roles or co-leading tasks can foster ownership and skill development.

Together, these design elements form a blueprint for building teams that are not only productive but also adaptive, inclusive, and rewarding. Whether in the classroom or workplace, intentional team design sets the stage for collaboration that lasts.

Team Roles and Responsibilities

Effective teamwork hinges on clearly defined roles that support both task completion and interpersonal dynamics. Organizational communication research identifies three essential categories of team roles: task roles, social roles, and boundary-spanning roles—each contributing uniquely to team success.

Task roles are goal-oriented functions that drive the team’s productivity and problem-solving. These roles include initiators, information seekers, coordinators, and evaluators—members who propose ideas, gather relevant data, organize efforts, and assess outcomes (Benne & Sheats, 2007; Ancona & Caldwell, 1992). For example, the initiator-contributor sparks new ideas, while the information seeker ensures decisions are grounded in accurate evidence. These roles are especially vital in academic group projects or workplace teams tackling complex tasks, where clarity, logic, and structure are paramount.

Social roles focus on relationship-building and maintaining group cohesion. These include encouragers, harmonizers, gatekeepers, and compromisers—members who foster trust, manage conflict, and ensure inclusive participation (Williams, 2012; Lasker et al., 2001). The encourager boosts morale and validates contributions, while the harmonizer helps resolve interpersonal tensions. Research shows that teams with strong social role engagement experience higher levels of psychological safety, collaboration, and long-term effectiveness (Gruman et al., 2016; Li et al., 2020). For students, embracing social roles can transform group work from a chore into a meaningful learning experience.

Boundary-spanning roles connect the team to external environments, facilitating communication, resource acquisition, and strategic alignment. These roles are often filled by individuals who liaise with stakeholders, represent the team’s interests, or bring in outside expertise (Tushman, 1977; Aldrich & Herker, 1977). In organizational settings, boundary spanners might be project managers or client-facing team members who translate external needs into actionable goals. In student teams, this could be someone who communicates with instructors, secures resources, or integrates feedback from outside collaborators. Boundary-spanning enhances innovation and adaptability by ensuring the team remains responsive to external demands (Williams, 2012; Curnin et al., 2015).

Together, these roles form a dynamic ecosystem of responsibilities that balance task execution, interpersonal harmony, and external engagement. Understanding and intentionally adopting these roles empowers teams to function more effectively, adapt to challenges, and achieve shared goals.

Establishing Norms and Communication Practices

Group norms are the invisible architecture of team behavior—guidelines that shape how members interact, make decisions, and resolve disagreements. Organizational communication research distinguishes between explicit norms, which are formally stated or written, and implicit norms, which are understood through repeated behavior or cultural expectations (Müller-Frommeyer & Kauffeld, 2021; Dahlgren, 2021). Norms can also be general, applying to the whole group (e.g., meeting punctuality), or role-specific, tailored to individual responsibilities (e.g., a team leader facilitating discussion or a recorder documenting decisions) (Galanes & Adams, 2020; LibreTexts, 2020).

Norms play a critical role in shaping participation. When norms encourage equal speaking time, active listening, and respectful disagreement, members are more likely to contribute ideas and engage in dialogue (Engleberg & Wynn, 2013). Conversely, unclear or exclusionary norms can silence voices and reinforce power imbalances. For college students, establishing inclusive norms—such as rotating facilitators or using structured turn-taking—can foster more democratic and dynamic collaboration.

Norms also influence accountability by setting expectations for task completion, attendance, and follow-through. Explicit norms, like written agreements or shared calendars, make responsibilities visible and reduce ambiguity (Lamberton & Minor-Evans, 2002). Implicit norms, such as peer pressure or shared values, can motivate behavior but may also lead to uneven enforcement. Research shows that teams with clear accountability norms experience higher trust and performance (Dettling, 2023; Kozlowski & Ilgen, 2006).

When it comes to conflict resolution, norms act as a compass. Teams with collaborative conflict cultures—where open dialogue and mutual respect are expected—are more likely to resolve disagreements constructively (Gelfand et al., 2012). In contrast, avoidant or dominating norms can escalate tensions or suppress dissent. Establishing norms for how conflict is addressed—such as using “I” statements, pausing for reflection, or involving a neutral facilitator—can transform conflict into a source of growth and innovation (Ramirez Marin et al., 2019).

Ultimately, norms are not static—they evolve with the team. Regular reflection and renegotiation of norms help teams adapt to new challenges and maintain psychological safety. For students, learning to co-create and uphold norms is a foundational skill for effective teamwork in any setting.

Advanced Dynamics of Team Communication

Beyond structure and roles, high-performing teams thrive on deeper interpersonal dynamics—trust, shared belief, constructive conflict, and meaningful feedback. Organizational communication research highlights four advanced dimensions that elevate team effectiveness: psychological safety, collective efficacy, conflict types, and feedback and recognition.

Psychological safety is the shared belief that team members can take interpersonal risks—such as asking questions, admitting mistakes, or challenging ideas—without fear of embarrassment or retaliation (Edmondson, 1999; CIPD, 2024). It’s a cornerstone of innovation, learning, and conflict resolution. Teams with high psychological safety engage in more open dialogue, experiment freely, and recover quickly from setbacks (Marom, 2024; Patil et al., 2023). Trust plays a complementary role: while psychological safety focuses on how others will respond to your vulnerability, trust reflects your confidence in their character and competence (Wietrak & Gifford, 2024). Together, they create a climate where feedback is welcomed, conflict is navigated constructively, and creativity flourishes.

Collective efficacy refers to a team’s shared belief in its ability to achieve goals and perform effectively (Bandura, 1997; Elms et al., 2023). It’s not about individual confidence, but mutual confidence in the group’s capability. High collective efficacy boosts motivation, coordination, and resilience—especially under pressure (Li et al., 2020; Saleem et al., 2022). However, overconfidence can backfire, leading to complacency or poor decision-making (Rapp et al., 2014). Communication practices such as goal alignment, feedback loops, and inclusive dialogue help calibrate collective efficacy and sustain performance.

Conflict types matter more than conflict itself. Research distinguishes between task conflict—disagreements about ideas, strategies, or decisions—and relational conflict, which stems from personality clashes or emotional tension (Jehn, 1997; Jehn et al., 2008). Task conflict, when managed well, can enhance creativity and decision quality by surfacing diverse perspectives (De Dreu, 2006; Jehn & Mannix, 2001). Relational conflict, however, tends to erode trust, reduce cohesion, and hinder performance. Norms that encourage respectful debate and discourage personal attacks help teams harness the benefits of task conflict while minimizing relational friction (Gaba & Joseph, 2023).

Feedback and recognition are vital communication practices that reinforce team effectiveness. Constructive feedback promotes learning, accountability, and continuous improvement (Cardenas, 2024; Pacheco, 2025). Recognition—whether formal or informal—boosts morale, engagement, and psychological safety (McKinsey, 2025; Carter, 2024). Teams thrive when feedback is timely, specific, and framed as a shared growth opportunity. Inclusive recognition practices that celebrate diverse contributions foster belonging and motivation. Together, feedback and recognition create a culture of appreciation and adaptability.

These advanced dynamics are not just “nice to have”—they’re essential for navigating complexity, building resilience, and unlocking the full potential of teams. For students and professionals alike, mastering these communication practices is key to leading and collaborating effectively in today’s fast-paced, diverse environments.

Insider Edge

Navigating Poor Delegation and Favoritism in Team Projects

Objective: To empower employees with strategies to assert their value, advocate for equitable treatment, and maintain motivation when working under managers who either fail to delegate effectively or show favoritism in task assignments.

The Problem: Delegation Dysfunction and Favoritism

Managers who struggle to delegate or favor certain team members can unintentionally:

- Undermine team trust and morale

- Create bottlenecks in decision-making

- Reduce opportunities for growth and visibility

- Foster resentment and disengagement among overlooked employees

“Delegation is empowering only when it is distributed equitably and aligned with employee capabilities and goals.” — Yukl & Fu (1999)

Strategy Toolkit for Employees

1. Initiate a Constructive Dialogue

- Use assertive but respectful language: “I’d love to take on more responsibility in areas where I can contribute meaningfully.”

- Frame your request around team success and personal development.

2. Document Your Contributions

- Keep a record of tasks completed, ideas proposed, and outcomes achieved.

- Use this data to advocate for fairer task distribution or recognition.

3. Seek Clarity on Role Expectations

- Ask for written or verbal clarification on your role in the project.

- Suggest regular check-ins to align on goals and responsibilities.

4. Build Peer Alliances

- Collaborate with colleagues to share knowledge and support each other.

- Use informal networks to stay informed and involved in key decisions.

5. Leverage Organizational Channels

- Use HR, mentorship programs, or employee resource groups to raise concerns.

- Frame feedback around improving team equity and performance—not personal grievance.

6. Reframe and Refocus

- Focus on what you can control: your effort, attitude, and visibility.

- Use overlooked opportunities to build new skills or innovate independently.

Empowerment Tip

“Favoritism in delegation undermines psychological safety and team cohesion. Employees must be equipped to advocate for equitable inclusion.” — Lee, Willis, & Tian (2018)

References

Yukl, G., & Fu, P. P. (1999). Determinants of delegation and consultation by managers. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 20(2), 219–232. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-1379(199903)20:2<219::AID-JOB922>3.0.CO;2-8

Lee, A., Willis, S., & Tian, A. W. (2018, March 2). When empowering employees works, and when it doesn’t. Harvard Business Review. Read the article

Robinson, C. (2025, March 21). The power of letting go: Why delegation drives organizational success. Forbes. Explore the insights

Orzach, R., & Quist, K. (2022). Empowerment in teams: When delegation prevents collaboration. MIT Department of Economics. Download the paper

Discussion Questions

- Think about the last team you were part of. How did the team’s communication norms (explicit or implicit) affect participation, accountability, or conflict resolution throughout the project? Give a specific example.

- Reflect on your usual role in teams. Do you tend to gravitate toward task, social, or boundary-spanning roles? How does this shape your experience in groups—and how comfortable would you be stepping into a different role?

- Have you experienced working in a virtual or hybrid team? What challenges did you face in building trust and psychological safety, and what communication strategies helped the team stay connected and effective?

- Based on your past experiences, what do you think is the ideal team size for high performance? Consider factors like task complexity, coordination needs, and diversity—what trade-offs should teams be aware of?

- Has your team ever dealt with conflict? If so, was it task-related (e.g., ideas and strategy) or relational (e.g., personalities and emotions)? How did the team handle the situation, and what could have improved the outcome?

- Describe a time when feedback or recognition made a difference in your team experience. Was it positive, constructive, or absent altogether? How did it affect motivation, learning, or team morale?

Section 9.4: Facilitating Team Coordination and Meetings

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, you should be able to:

- Analyze the factors that contribute to the long-term viability of collaborative teams, including capacity alignment, shared purpose, and psychological safety.

- Evaluate strategies for navigating capacity tensions in team settings, such as internal accommodation and external orientation, using current organizational research.

- Design systems that foster sustained engagement, including onboarding protocols, norm maintenance, and recognition rituals that reinforce team cohesion.

- Assess the role of technology in collaboration sustainability, identifying both supportive and obstructive effects in hybrid and remote team environments.

- Apply principles of inclusive team culture to develop resilience, adaptability, and continuity in evolving collaborative projects.

Effective team coordination doesn’t happen by accident—it’s built through intentional communication, shared expectations, and structured interaction. In today’s fast-paced and increasingly virtual environments, teams must navigate complex tasks, diverse perspectives, and shifting priorities. Organizational communication research shows that the way teams establish norms, prepare for meetings, and follow through on decisions directly influences their performance, satisfaction, and long-term cohesion (Morgan et al., 2021; Kauffeld & Lehmann-Willenbrock, 2012).

Team norms—whether explicit (written contracts) or implicit (unspoken expectations)—create psychological safety and accountability, shaping how members participate and resolve conflict (Gelfand et al., 2012; Müller-Frommeyer & Kauffeld, 2021). Meetings, meanwhile, serve as critical coordination points. Studies reveal that functional meeting behaviors—such as collaborative problem-solving and action planning—are strongly linked to team productivity and organizational success, while dysfunctional behaviors like complaining or dominating discussion can undermine outcomes (Kauffeld & Lehmann-Willenbrock, 2012).

This section explores how teams can design and manage their coordination practices across four key phases: setting norms, preparing for engagement, facilitating meetings, and following through. Whether you’re leading a student organization, contributing to a workplace team, or collaborating on a class project, these strategies will help you build trust, streamline communication, and get results.

Establishing Norms for Effective Collaboration

Team norms are the behavioral agreements—spoken or unspoken—that shape how members interact, make decisions, and resolve conflict. These norms can be explicit, such as written team contracts or documented expectations, or implicit, emerging organically through repeated behaviors and shared assumptions (Müller-Frommeyer & Kauffeld, 2021). Whether formal or informal, norms serve as the foundation for psychological safety, accountability, and shared understanding—three pillars of effective collaboration.

Psychological safety, defined as the belief that one can speak up, ask questions, or admit mistakes without fear of embarrassment or punishment, is consistently linked to team learning, innovation, and engagement (Edmondson, 1999; Gelfand et al., 2012). When norms explicitly encourage respectful listening, inclusive participation, and openness to feedback, team members are more likely to contribute ideas and challenge assumptions. For example, meeting expectations that include rotating facilitators, structured turn-taking, and feedback protocols help democratize communication and reduce dominance by a few voices (Kauffeld & Lehmann-Willenbrock, 2012).