Chapter 5: What Drives Us: Understanding Employee Motivation Through Human Needs

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, you should be able to do the following:

- Explain how employee motivation affects performance in real-world workplace scenarios.

- Identify and categorize the basic psychological needs that drive employee behavior.

- Analyze how perceptions of fairness are formed—and how they impact job attitudes and actions.

- Evaluate the role of rewards and punishments in shaping motivation and performance.

- Apply classic and contemporary motivation theories to diagnose and solve performance challenges at work.

What Drives Us: Understanding Employee Motivation Through Human Needs

What inspires someone to deliver exceptional service, promote a company’s products with enthusiasm, or exceed performance goals? Understanding this question is essential for managing workplace behavior—whether you’re leading a team, supporting a colleague, or evaluating your own performance. Put simply: if someone isn’t performing well, what might be the reason?

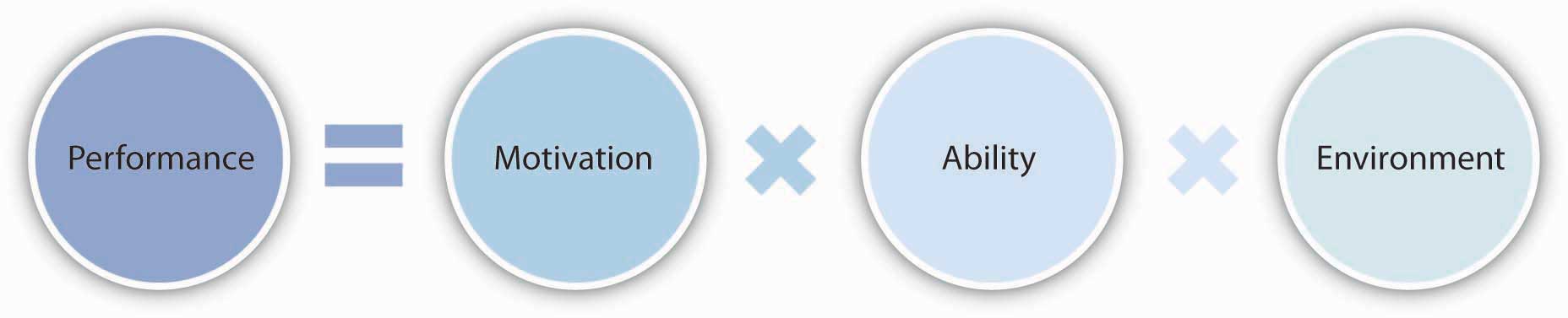

According to a foundational model in organizational behavior, job performance is a function of three key factors: motivation, ability, and environment (Mitchell, 1982; Porter & Lawler, 1968). This relationship can be expressed as:

Let’s break that down:

- Motivation refers to the internal drive to achieve goals and pursue excellence. A motivated employee puts effort into their tasks and strives to succeed.

- Ability includes the skills, knowledge, and competencies required to perform a job effectively. Even the most motivated person may struggle without the right capabilities.

- Environment encompasses external conditions—such as access to resources, information, and support—that enable performance.

Each factor plays a unique role. For example, a motivated employee sweeping a floor may perform well because the task requires minimal skill or resources. But motivation alone won’t help someone design a house without architectural expertise. In short, motivation is necessary—but not sufficient—for high performance.

What Motivates People?

Why do some employees chase excellence while others simply clock in and count the hours? The answer isn’t straightforward. Human behavior is complex, and motivation is influenced by a variety of psychological, social, and contextual factors.

To make sense of it, researchers have developed multiple theories of motivation. In this chapter, we’ll explore two major categories:

- Need-Based Theories: These focus on what people need—such as safety, belonging, or achievement—and how fulfilling those needs drives behavior.

- Process Theories: These examine how people make decisions, set goals, and evaluate fairness and outcomes in the workplace.

Together, these theories offer powerful tools for understanding what energizes employees—and how managers can create environments that support motivation and performance.

Section 5.1: Spotlight

Motivation and Communication at Daugherty Business Solutions

Daugherty Business Solutions, a St. Louis–based technology consulting firm, has cultivated a workplace culture that emphasizes communication, growth, and employee empowerment. Leadership at Daugherty views motivation not as a one-way directive but as a dynamic, two-way process rooted in dialogue and development. This approach aligns with modern organizational communication theory, which emphasizes the importance of feedback loops, transparent messaging, and shared meaning in fostering employee engagement (Robbins & Judge, 2022). By investing in mentorship, internal mobility, and inclusive employee resource groups, Daugherty creates an environment where employees feel heard, valued, and motivated to contribute.

The company’s practices reflect a nuanced understanding of employee needs, closely mirroring Maslow’s Hierarchy. Basic needs are met through competitive compensation and benefits, while psychological and self-actualization needs are addressed through professional development programs and a culture of belonging (PeopleHR, 2024). Daugherty’s DEI initiatives and internal networking groups—such as Women LEAD and the Black Consultants Network—further reinforce a sense of community and purpose. These communication channels not only support individual growth but also strengthen organizational cohesion.

Fairness and equity are central to Daugherty’s internal narrative, though employee reviews suggest some inconsistencies in execution. While many consultants praise the collaborative culture and leadership’s investment in career growth, others cite concerns about favoritism and uneven communication from upper management (Indeed, 2024). This tension highlights the importance of consistent superior-subordinate communication and the perception of procedural justice—key factors in employee satisfaction and retention (Greenberg, 1990). Daugherty’s emphasis on promoting from within and recognizing individual contributions reflects an effort to balance equity with performance-based advancement.

In terms of rewards and consequences, Daugherty leans toward positive reinforcement. Employees are motivated through learning opportunities, autonomy, and recognition, though some note that bonuses and merit increases are modest. The company appears to avoid punitive measures, instead using performance-based reassignment or layoffs when necessary. This approach aligns with Herzberg’s Two-Factor Theory, which distinguishes between hygiene factors (e.g., pay, job security) and motivators (e.g., achievement, recognition) as separate but essential components of job satisfaction (Herzberg, 1968).

Ultimately, Daugherty’s motivational strategy is best explained by a blend of Herzberg’s theory, McClelland’s Needs Theory, and Equity Theory. The firm fosters achievement and affiliation through its consulting model, while striving to maintain fairness and transparency in its communication practices. While not without challenges, Daugherty’s approach demonstrates how thoughtful organizational communication can shape motivation, performance, and culture in a knowledge-driven workplace.

References

Greenberg, J. (1990). Organizational justice: Yesterday, today, and tomorrow. Journal of Management, 16(2), 399–432.

Herzberg, F. (1968). One more time: How do you motivate employees? Harvard Business Review.

Indeed. (2024). Daugherty Business Solutions employee reviews. https://www.indeed.com/cmp/Daugherty-Business-Solutions/reviews

PeopleHR. (2024). Motivational theories in the workplace to improve productivity. https://www.peoplehr.com/en-gb/resources/blog/motivation-theory-in-the-workplace/

Robbins, S. P., & Judge, T. A. (2022). Organizational behavior (19th ed.). Pearson.

Discussion Questions

- How does Daugherty Business Solutions use organizational communication to align individual employee motivations with the company’s goals? In what ways might two-way communication between management and employees enhance motivation within the organization?

- How does Daugherty’s leadership identify and address the basic needs of employees through its communication strategies? How might Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs influence the way the company prioritizes these needs in its messaging and policies?

- How does Daugherty’s management communicate fairness and equity among employees, particularly in superior-subordinate relationships? What role does transparency in communication play in shaping perceptions of procedural and distributive justice within the organization?

- How does Daugherty utilize communication to reinforce rewards and address performance issues? Which motivation theories (e.g., Herzberg’s Two-Factor Theory, Equity Theory, or McClelland’s Needs Theory) best explain the company’s approach to analyzing and resolving performance problems?

Section 5.2: Need-Based Theories of Motivation

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, you should be able to do the following:

- Describe Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs and explain how different types of needs motivate behavior at work.

- Compare Maslow’s theory with Alderfer’s ERG model and identify how ERG refines our understanding of motivation.

- Distinguish between factors that lead to motivation versus those that cause dissatisfaction and explain how this informs management strategy.

- Define the acquired needs for achievement, affiliation, and power, and analyze how these needs influence employee behavior, teamwork, and leadership styles.

Needs-Based Theories of Motivation: A Contemporary Perspective

Modern organizational communication research continues to affirm that employees behave in goal-directed ways to satisfy internal needs, but it also emphasizes the dynamic and context-sensitive nature of those needs. For example, an employee who frequently engages in casual conversations with coworkers may be fulfilling a social need for belonging, while another who volunteers for high-visibility projects may be driven by esteem or self-actualization needs. These foundational theories help organizations understand what motivates people and how to design environments that support those motivations.

Four major theories still guide this understanding:

- Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

- ERG Theory (Existence, Relatedness, Growth)

- Herzberg’s Two-Factor Theory

- McClelland’s Acquired Needs Theory

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs in Today’s Workplace

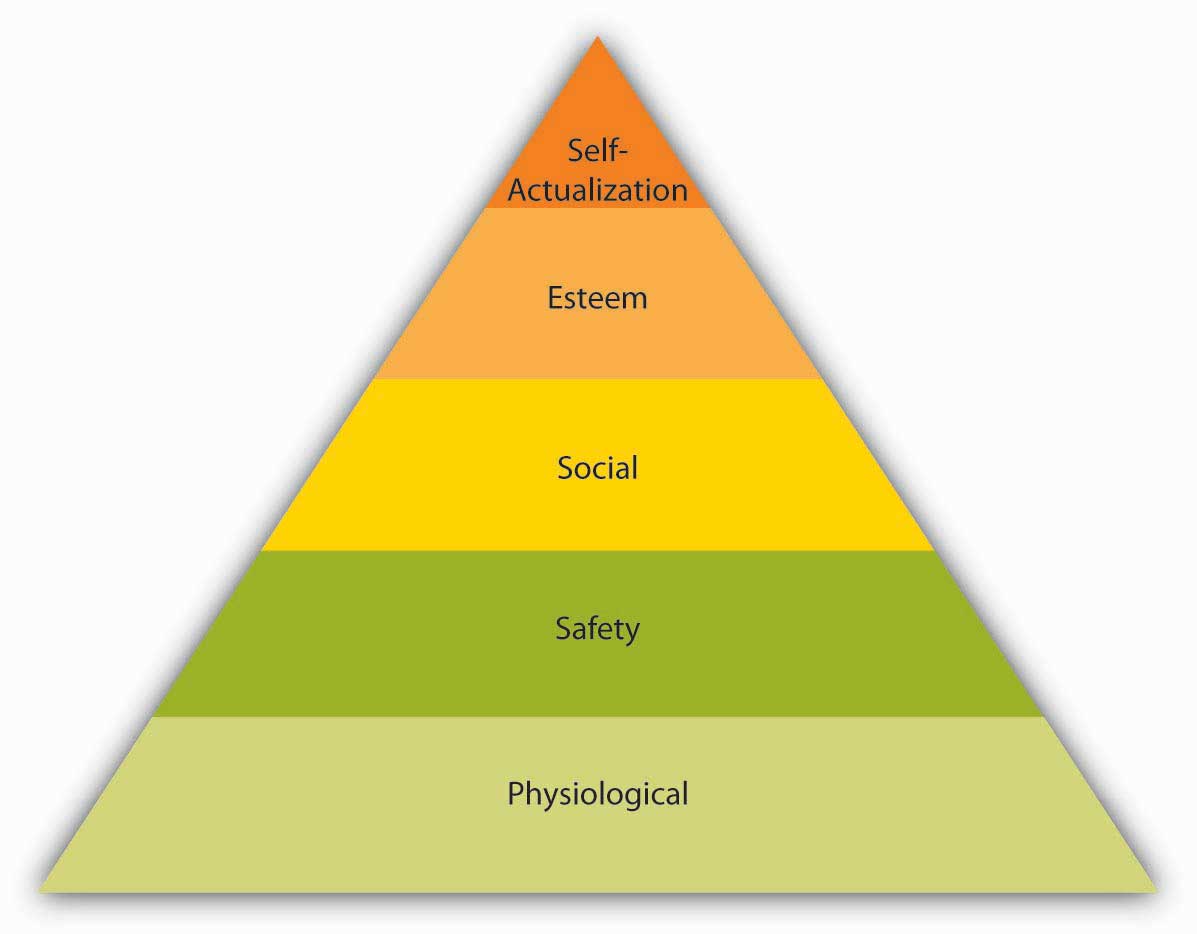

Maslow’s theory remains one of the most recognized frameworks in motivation research. He proposed that human needs are arranged in a hierarchy, where lower-level needs must be met before higher-level needs become motivational drivers (Maslow, 1943; Maslow, 1954). These include:

- Physiological Needs: Fair wages, access to food, and comfortable workspaces. For example, companies like Google and Salesforce offer free meals and wellness spaces to meet basic needs.

- Safety Needs: Job security, health benefits, and safe working conditions. Remote work policies and mental health support have become central to meeting these needs post-pandemic.

- Social Needs: Team-building, inclusive communication, and collaborative culture. Platforms like Slack and Microsoft Teams facilitate digital belonging.

- Esteem Needs: Recognition programs, promotions, and meaningful titles. LinkedIn’s public endorsements and internal “kudos” systems are modern tools for esteem-building.

- Self-Actualization: Opportunities for growth, autonomy, and purpose-driven work. Companies like Patagonia and IDEO encourage employees to pursue personal development and social impact projects.

While Maslow’s model offers a useful framework, contemporary research challenges its rigid hierarchy. Employees may pursue multiple needs simultaneously, and satisfying a need doesn’t always eliminate its motivational power (Neher, 1991; Rauschenberger et al., 1980). Moreover, cultural and generational differences influence how needs are prioritized and expressed in the workplace (OpenStax, 2023).

Organizations can use Maslow’s framework to design environments that support employee motivation:

| Need Level | Workplace Strategies |

|---|---|

| Physiological | Fair wages, access to food and water, comfortable workspaces |

| Safety | Health insurance, retirement plans, job security, safe working conditions |

| Social | Team-building activities, collaborative culture, inclusive communication |

| Esteem | Recognition programs, promotions, meaningful job titles |

| Self-Actualization | Professional development, challenging projects, autonomy, purpose-driven work |

ERG Theory: A Flexible Framework for Workplace Motivation

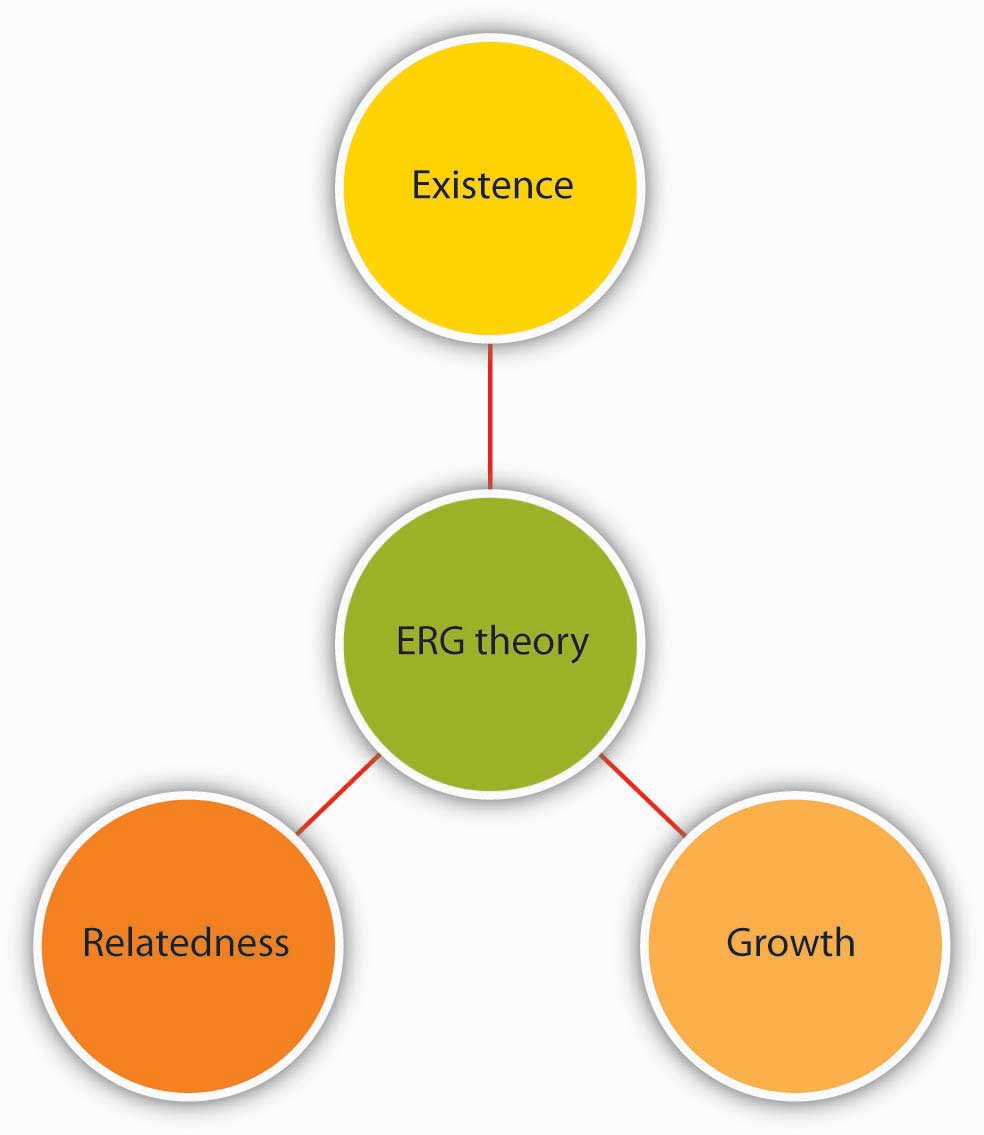

Clayton Alderfer’s ERG Theory (1969) remains a relevant and adaptable model for understanding human motivation in organizational settings. Building on Maslow’s hierarchy, Alderfer condensed human needs into three categories—Existence, Relatedness, and Growth—while removing the rigid sequencing of Maslow’s model. This flexibility makes ERG Theory especially applicable to modern workplaces, where employees often navigate multiple needs simultaneously and in non-linear ways.

- Existence Needs refer to basic survival and security, including financial stability, health, and safety. In today’s organizations, these are addressed through competitive compensation, comprehensive health benefits, and safe work environments.

- Relatedness Needs involve social connection, interpersonal relationships, and feeling valued. With the rise of hybrid work, tools like Slack and Zoom, along with inclusive communication practices, help foster belonging and collaboration across physical boundaries.

- Growth Needs encompass personal development, achievement, and self-actualization. Companies like Adobe and Atlassian promote growth through innovation labs, mentorship programs, and purpose-driven initiatives.

ERG Theory improves upon Maslow’s framework in several key ways. First, it allows for simultaneous need activation—employees may seek both social connection and professional advancement at the same time (Wanous & Zany, 1977). Second, the Frustration–Regression Principle explains how unmet higher-level needs can lead individuals to refocus on lower-level needs. For instance, an employee blocked from career advancement may turn to social engagement for fulfillment (Caulton, 2020).

Recent organizational communication research highlights ERG Theory’s relevance in fostering collaboration and navigating competitive environments. As artificial intelligence reshapes workflows and accelerates decision-making, ERG Theory offers a roadmap for maintaining human-centered motivation and communication. Studies show that communal values—such as well-being and inclusion—are increasingly linked to ERG needs, especially in cross-functional teams and knowledge-sharing environments (Creed, Zutshi, & Baker, 2025).

Figure 5.4

ERG theory includes existence, relatedness, and growth.

Source: Based on Alderfer, C. P. (1969). An empirical test of a new theory of human needs. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 4, 142–175.

Managers can apply ERG Theory by recognizing that motivation is dynamic and context-dependent:

- Address existence needs with fair compensation, flexible work arrangements, and wellness programs.

- Support relatedness needs through team-building, transparent communication, and inclusive leadership.

- Foster growth needs by offering autonomy, skill development, and meaningful challenges.

By attending to the full spectrum of human needs, organizations can build resilient, motivated, and communicatively agile teams—especially in times of change and uncertainty.

Herzberg’s Two-Factor Theory: Motivation vs. Dissatisfaction in Modern Workplaces

Frederick Herzberg’s Two-Factor Theory remains a foundational framework in organizational psychology and communication, offering a nuanced understanding of what drives employee satisfaction and dissatisfaction. Herzberg’s research revealed that the factors contributing to job satisfaction—termed motivators—are distinct from those causing dissatisfaction—known as hygiene factors (Herzberg, Mausner, & Snyderman, 1959; Herzberg, 1965). This dual-factor model continues to influence how organizations design roles, manage teams, and communicate with employees.

Hygiene Factors: Preventing Discomfort, Not Driving Engagement

Hygiene factors are extrinsic elements related to the job environment, such as company policies, supervision quality, salary, working conditions, and job security. While these do not inherently motivate employees, their absence can lead to frustration and disengagement. For example, inadequate remote work policies or unclear communication from leadership can erode trust and morale. In hybrid and remote settings, organizations now emphasize digital infrastructure, psychological safety, and equitable access to resources to maintain hygiene standards (Mitsakis & Galanakis, 2022).

Motivators: Fueling Purpose and Performance

Motivators are intrinsic to the job itself and include achievement, recognition, meaningful work, increased responsibility, and opportunities for growth. These elements tap into deeper psychological needs for autonomy, mastery, and purpose. Modern organizations like HubSpot and Atlassian use peer recognition platforms, stretch assignments, and purpose-driven missions to foster intrinsic motivation. Research shows that employees who perceive their work as meaningful and aligned with personal values report higher engagement and lower turnover (Nickerson, 2025).

Criticisms and Complexity

Herzberg’s theory has faced methodological critiques. Some scholars argue that individuals may attribute positive outcomes to internal factors and negative ones to external conditions, potentially biasing results (House & Wigdor, 1967; Cummings & Elsalmi, 1968). Additionally, the classification of factors is not always clear-cut. For instance, salary may function as both a hygiene factor and a motivator when tied to recognition or advancement. Similarly, supervision can either demotivate through micromanagement or inspire through mentorship and support.

Recent studies suggest that the impact of these factors is context-dependent and influenced by organizational communication practices. Transparent feedback, inclusive leadership, and participatory decision-making can transform hygiene factors into sources of motivation (Abdulhamidova, 2021).

Practical Implications for Managers

Herzberg’s theory offers actionable insights for leaders and communicators:

- Eliminate dissatisfaction by ensuring strong hygiene factors—fair policies, safe environments, and respectful treatment.

- Drive engagement by enriching jobs with autonomy, recognition, and opportunities for growth.

- Communicate intentionally, tailoring messages to reinforce both hygiene and motivational elements.

In essence, removing discomfort creates a neutral baseline, but adding meaning and challenge cultivates true engagement. As organizations navigate evolving work models and employee expectations, Herzberg’s framework remains a valuable guide for designing motivating and communicatively effective workplaces.

Acquired-Needs Theory: Motivation Shaped by Experience and Communication

David McClelland’s Acquired-Needs Theory remains one of the most empirically supported frameworks for understanding workplace motivation. Unlike Maslow or Alderfer, McClelland argued that motivational needs are not innate but shaped by life experiences and social environments (McClelland, 1961). These needs—achievement (nAch), affiliation (nAff), and power (nPow)—develop over time and influence how individuals behave, communicate, and lead in organizational contexts.

Measuring Motivation: Thematic Apperception and Beyond

McClelland originally used the Thematic Apperception Test (TAT) to identify dominant needs by analyzing stories people wrote about ambiguous images (Spangler, 1992). Today, organizations use behavioral assessments, 360-degree feedback, and AI-driven sentiment analysis to gauge motivational drivers and tailor communication strategies accordingly (Arogundade & Akpa, 2023).

- A story or behavior focused on innovation and goal-setting may indicate high nAch.

- Emphasis on relationships and team dynamics suggests high nAff.

- Themes of influence and strategic control point to high nPow.

Need for Achievement (nAch)

Individuals high in nAch are goal-oriented, seek feedback, and thrive in roles with measurable outcomes—such as sales, engineering, or entrepreneurship (Harrell & Stahl, 1981; Trevis & Certo, 2005). They prefer merit-based systems and often excel in competitive environments. However, they may struggle in leadership roles if they resist delegation or undervalue team development (McClelland & Burnham, 1976).

Modern organizations support high achievers by offering stretch assignments, performance dashboards, and recognition tied to results. Communication strategies that emphasize clarity, challenge, and autonomy resonate strongly with this group (Baptista et al., 2023).

Need for Affiliation (nAff)

Those high in nAff prioritize interpersonal harmony and being liked. They flourish in collaborative roles such as teaching, counseling, or customer service (Wong & Csikszentmihalyi, 1991). In management, however, excessive concern for social approval may hinder effectiveness, especially when critical feedback or tough decisions are required.

Organizations can support nAff-driven employees by fostering inclusive cultures, peer recognition systems, and emotionally intelligent communication. Leaders must balance empathy with accountability to ensure team performance doesn’t stagnate.

Need for Power (nPow)

Individuals high in nPow seek influence and control, which can manifest as either personal power (for prestige) or institutional power (to improve systems). When aligned with organizational goals, nPow is linked to effective leadership, advocacy, and strategic decision-making (Spangler & House, 1991; Spreier, 2006).

In today’s workplace, institutional power is increasingly valued, especially in roles that require cross-functional leadership and change management. Communication that emphasizes vision, impact, and strategic alignment helps channel nPow constructively.

Managerial Implications

McClelland’s theory offers actionable insights for tailoring motivation and communication:

- High nAch: Set challenging goals, provide performance feedback, and reward results.

- High nAff: Promote team cohesion, peer support, and inclusive dialogue.

- High nPow: Offer leadership roles, decision-making authority, and strategic influence.

Understanding dominant needs allows managers to anticipate behavioral tendencies and design communication strategies that resonate with individual drivers. This is especially critical when promoting high performers into leadership roles, where their motivational profile may shape how they lead and connect with others.

Applying Needs-Based Theories in Organizational Communication

Modern organizations use needs-based theories to shape internal communication strategies, leadership development, and employee engagement initiatives. For instance, managers are encouraged to tailor feedback and recognition to individual motivational profiles, rather than applying one-size-fits-all approaches (Seneca Polytechnic, 2023). Understanding these needs helps leaders foster psychological safety, reduce turnover, and enhance performance.

Importantly, employees respond differently to the same treatment depending on which needs are most salient. Public praise may boost esteem for one employee but feel uncomfortable for another who values social harmony. This underscores the importance of communication agility—adapting messages and interactions to meet diverse motivational drivers.

By recognizing and addressing the evolving needs of their workforce, organizations can create environments that are not only productive but also emotionally intelligent and ethically grounded.

Discussion Questions

- Many managers assume that if an employee is not performing well, the reason must be a lack of motivation. Do you think this reasoning is accurate? What other factors might contribute to poor performance? Discuss the potential problems with this assumption and how managers can better diagnose performance issues.

- Review Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. Do you agree with the specific ranking of employee needs in the hierarchy? Can you think of examples where employees might prioritize higher-level needs (e.g., self-actualization) over lower-level ones (e.g., safety)? How might cultural or individual differences affect the hierarchy?

- How can an organization effectively satisfy employee needs as outlined in Maslow’s hierarchy? Provide examples of workplace practices or policies that address each level of the hierarchy (e.g., physiological, safety, social, esteem, and self-actualization needs).

- Which motivation theory (e.g., Maslow’s hierarchy, Herzberg’s two-factor theory, ERG theory, or McClelland’s acquired-needs theory) do you find most useful in explaining why people behave in certain ways? Explain your choice with examples from personal experience or workplace scenarios. How does this theory help managers design effective motivational strategies?

- Review the hygiene factors and motivators in Herzberg’s two-factor theory of motivation. Do you agree with the distinction between hygiene factors and motivators? Why or why not? Are there any hygiene factors (e.g., salary, supervision) that you believe could also act as motivators? Provide examples to support your argument.

- A friend of yours demonstrates strong traits of achievement motivation: she is competitive, requires frequent and immediate feedback, and enjoys accomplishing tasks and improving her performance. She has recently been promoted to a managerial position and seeks your advice. What challenges might she face as a manager due to her high need for achievement? What strategies can she use to balance her personal drive with the need to motivate and develop her team? Provide specific examples of how she can delegate effectively and focus on team success.

Section 5.3: Process-Based Theories of Motivation

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter you should be able to:

- Analyze how employees judge fairness in the workplace—especially when rewards, recognition, and promotions are distributed.

- Differentiate among three types of organizational justice: distributive, procedural, and interactional fairness—and evaluate how each influences employee attitudes and performance.

- Apply expectancy theory by identifying the key questions employees ask themselves when deciding whether to invest effort at work.

- Evaluate how learning and reinforcement strategies (e.g., rewards, punishments, feedback schedules) can be used by managers to shape and sustain motivated behavior.

The Thinking Behind the Effort

While need-based theories focus on what people are trying to satisfy, process-based theories explore how individuals make decisions about effort and engagement. These theories view motivation as a rational, cognitive process shaped by perceptions of fairness, expectations of outcomes, and the consequences of behavior (Mehta, 2023). In today’s dynamic work environments—especially those influenced by hybrid models, digital platforms, and rapid change—understanding these mental processes is essential for effective organizational communication and leadership.

Rather than assuming behavior is driven solely by unmet needs, process theories ask:

- What do employees believe will happen if they put in effort?

- Do they perceive fairness in how rewards are distributed?

- How do past consequences shape future behavior?

Three foundational process-based theories help explain why people choose to engage—or disengage—at work:

Equity Theory: Motivation Through Fairness and Comparison

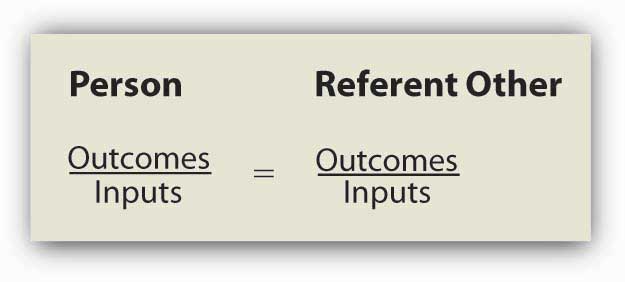

Developed by J. Stacy Adams, Equity Theory posits that individuals are motivated by a sense of fairness in social exchanges. Employees compare their input–outcome ratios (e.g., effort vs. pay) to those of peers. Perceived inequity—such as unequal pay for similar work—can lead to demotivation, reduced effort, or even turnover (Adams, 1965).

Modern organizations address equity through transparent compensation policies, inclusive recognition systems, and open communication. For example, companies like Buffer publicly share salary formulas to reinforce fairness and trust.

Figure 5.7

Equity is determined by comparing one’s input-outcome ratio with the input-outcome ratio of a referent. When the two ratios are equal, equity exists.

Source: Based on Adams, J. S. (1965). Inequity in social exchange. In L. Berkowitz (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology: Vol. 2 (pp. 267–299). New York: Academic Press.

If your reaction is something like, “That’s unfair,” your response aligns with Equity Theory, developed by J. Stacey Adams (1965). This theory proposes that individuals are motivated by a desire for fairness in social exchanges—especially in the workplace.

The Equity Equation

At the heart of Equity Theory is the idea that people compare their inputs (effort, skills, experience, time) and outcomes (pay, recognition, benefits) to those of others—called referents. Motivation is influenced by whether we perceive our input-to-outcome ratio to be equal to that of our referent.

- Inputs: What we contribute—e.g., effort, loyalty, education, flexibility

- Outcomes: What we receive—e.g., salary, praise, promotions, job security

- Referents: People we compare ourselves to—e.g., coworkers, peers in other companies, our past selves

If we perceive equity, we feel satisfied and motivated. If we perceive inequity, we experience tension and may take action to restore balance.

Who Is the Referent?

Referents may be:

- A specific person (e.g., a coworker with the same job)

- A group or category (e.g., entry-level employees in similar organizations)

Comparisons are meaningful only when the referent is perceived as comparable. For example, a student worker wouldn’t reasonably compare themselves to the CEO.

Reactions to Perceived Inequity

When employees perceive unfairness, they may respond in several ways (Carrell & Dittrich, 1978; Goodman & Friedman, 1971; Greenberg, 1993):

Table 5.1 Potential Responses to Inequity

| Response | Example |

|---|---|

| Distort perceptions | “Maybe they’re more skilled than I thought.” |

| Increase referent’s inputs | Encourage the other person to take on more work |

| Reduce own inputs | Put in less effort or lower performance |

| Increase own outcomes | Ask for a raise—or resort to unethical behavior like theft |

| Change referent | Compare oneself to someone worse off |

| Leave the situation | Quit the job |

| Seek legal action | File a complaint if inequity violates laws (e.g., gender-based pay gaps) |

Overpayment Inequity

Originally, Equity Theory predicted that over-rewarded individuals would feel guilt and increase effort. However, research shows that people experience less distress when overpaid and often rationalize the imbalance (Austin & Walster, 1974; Evan & Simmons, 1969).

Individual Differences in Reactions to Inequity

Not everyone reacts to inequity the same way. Equity sensitivity is a personality trait that influences how strongly people respond to fairness issues (Huseman, Hatfield, & Miles, 1987):

- Equity Sensitives: Expect balanced exchanges and feel distressed by inequity.

- Benevolents: Give more than they receive and are less concerned with fairness.

- Entitleds: Expect more rewards for less input.

Organizations should be aware of these differences when designing reward systems and managing employee expectations.

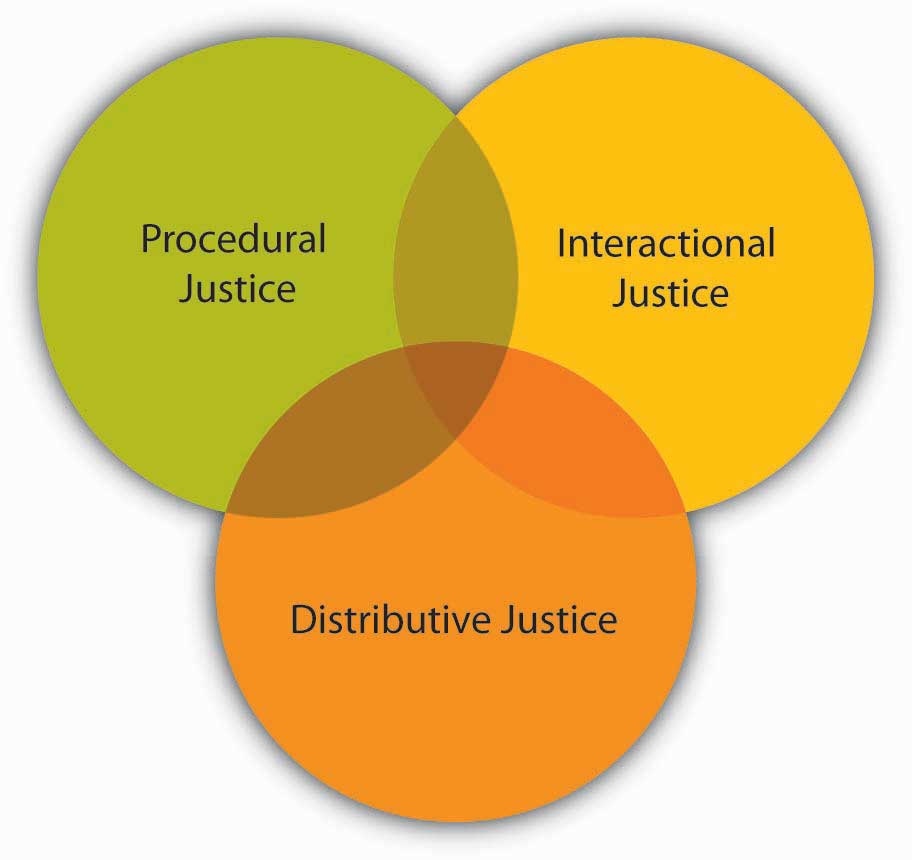

Beyond Equity: Procedural and Interactional Justice

Equity Theory focuses on distributive justice—the fairness of outcomes. But fairness also includes:

Procedural Justice

Refers to the fairness of decision-making processes. Employees care about how decisions are made, especially when outcomes are unfavorable (Brockner & Wiesenfeld, 1996). Fair procedures signal future opportunity and organizational respect (Cropanzano, Bowen, & Gilliland, 2007).

Ways to enhance procedural justice:

- Provide advance notice (Kidwell, 1995)

- Allow employee voice in decisions (Alge, 2001; Kernan & Hanges, 2002)

- Offer clear explanations (Schaubroeck et al., 1994)

- Ensure consistency in treatment (Bauer et al., 1998)

Interactional Justice

Refers to the quality of interpersonal treatment—respect, dignity, and kindness. Even when outcomes are negative, respectful communication can buffer stress and improve reactions (Greenberg, 2006).

Why Justice Matters

Justice perceptions affect key outcomes:

- Higher job performance

- Greater organizational commitment

- More citizenship behaviors

- Improved customer satisfaction

- Reduced stress and retaliation

Ignoring justice can lead to unionization efforts, turnover, and workplace deviance (Blader, 2007; Skarlicki & Folger, 1997).

Workplace Strategy Pack

How Supervisors Can Strive to Be Fair

Purpose: To equip supervisors with actionable strategies for fostering fairness in the workplace through ethical communication, inclusive leadership, and organizational justice principles.

Why Fairness Matters

Fairness is a cornerstone of employee trust, engagement, and performance. Research shows that employees who perceive their supervisors as fair are more satisfied, committed, and less likely to disengage or leave the organization (Adamovic, 2023). Fairness also reduces negative emotions and promotes psychological safety, especially when supervisors communicate difficult decisions transparently and respectfully (Thornton-Lugo & Rupp, 2021).

Types of Workplace Fairness

According to Kang and Fajardo (2023), fairness in the workplace includes four dimensions:

- Distributive fairness: Equitable distribution of rewards and resources

- Procedural fairness: Transparent and consistent decision-making processes

- Interactional fairness: Respectful and dignified interpersonal treatment

- Informational fairness: Honest and timely sharing of relevant information

Supervisors must attend to all four to build a culture of fairness.

Supervisor Strategies for Fairness

| Strategy | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Listen Actively | Create space for employee voice and feedback | Use regular check-ins and anonymous surveys |

| Communicate Transparently | Explain decisions clearly and consistently | Share rationale behind promotions or policy changes |

| Apply Policies Consistently | Avoid favoritism or bias in enforcement | Use standardized performance review criteria |

| Acknowledge Emotions | Recognize how decisions affect employees emotionally | Validate concerns during layoffs or restructuring |

| Model Respect | Treat all employees with dignity, regardless of role | Avoid dismissive language or public criticism |

| Promote Equity | Ensure fair access to opportunities and resources | Rotate leadership roles in team projects |

Communication Tip

“Fairness isn’t just about the outcome—it’s about how the outcome is communicated. Employees judge fairness by how they’re treated during the process.” — Adapted from Bies & Shapiro (1987)

References

Adamovic, M. (2023). From fair supervisor to satisfied employee: A comparative study of six organizational justice mechanisms. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 38(8), 576–596. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMP-10-2022-0566

Kang, M., & Fajardo, O. K. (2023, July 20). What does “fairness” mean to employees? New tools for evaluating internal communication. Institute for Public Relations. https://instituteforpr.org/what-does-fairness-mean-to-employees-new-tools-for-evaluating-internal-communication/

Thornton-Lugo, M. A., & Rupp, D. E. (2021). The communication of justice, injustice, and necessary evils: An empirical examination. SAGE Open, 11(3), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440211040796

Bies, R. J., & Shapiro, D. L. (1987). Interactional fairness judgments: The influence of causal accounts. Social Justice Research, 1(2), 199–218. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01048016

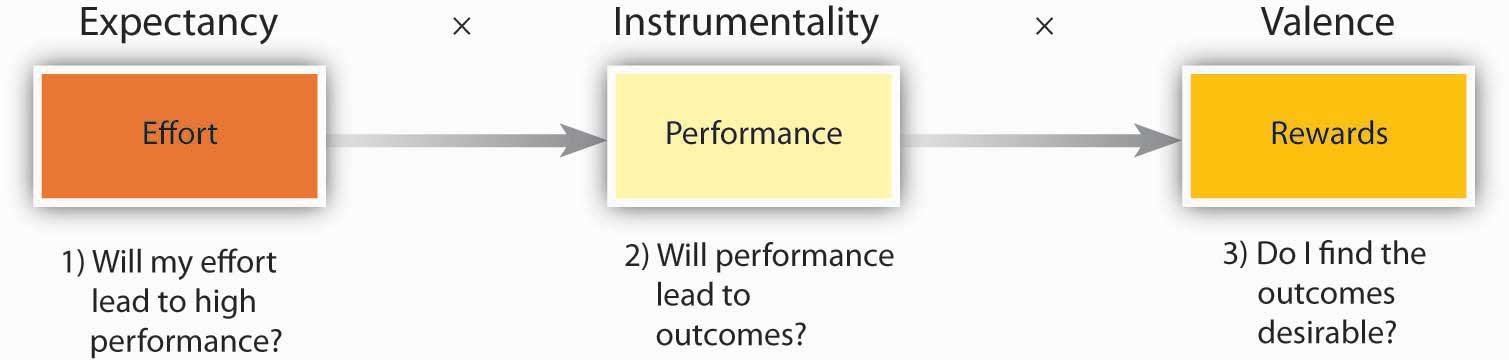

Expectancy Theory: Motivation as a Rational Calculation

Expectancy Theory, developed by Victor Vroom (1964) and expanded by Porter and Lawler (1968), views motivation as a rational process in which individuals evaluate their effort, performance, and the value of potential outcomes. Rather than being driven solely by unmet needs, people ask themselves three key questions before deciding how much effort to invest in a task.

Figure 5.9 Summary of Expectancy Theory

Sources: Based on Porter, L. W., & Lawler, E. E. (1968). Managerial attitudes and performance. Homewood, IL: Irwin; Vroom, V. H. (1964). Work and motivation. New York: Wiley.

The first question is about expectancy: “If I try harder, will I perform better?” This reflects the belief that effort leads to performance. For example, a student who believes that studying will improve their exam score is more likely to put in the effort. The second question concerns instrumentality: “If I perform well, will I be rewarded?” This is the belief that performance leads to outcomes, such as praise, promotions, or bonuses. Finally, individuals consider valence: “Do I value the reward?” If the outcome is desirable—such as a raise, recognition, or career advancement—motivation increases. When all three perceptions are positive, individuals are more likely to be motivated.

Expectancy Theory has received strong empirical support and remains one of the most widely accepted models of workplace motivation (Heneman & Schwab, 1972; Van Eerde & Thierry, 1996). Its intuitive appeal lies in its simplicity and applicability across various settings. Consider a concession stand employee who typically sells 100 snack combos per day. If their manager asks them to sell 300, the employee will mentally evaluate: Can I do it (expectancy)? Will I be rewarded if I do (instrumentality)? Do I care about the reward (valence)? If the answer to all three is yes, motivation is likely to increase.

Managerial Applications: Shaping Motivation

Managers can influence each component of the expectancy equation to foster motivation.

To improve expectancy, managers must ensure that employees believe their effort will lead to performance. This may involve training, clarifying roles, and removing obstacles. If employees lack skills or feel that politics, favoritism, or unclear expectations determine success, expectancy will suffer. Encouragement and feedback can also help employees with low self-confidence or external locus of control believe in their ability to succeed.

To strengthen instrumentality, managers must clearly link performance to rewards. This means implementing merit-based systems, offering bonuses, and publicizing recognition programs. However, rewards must be perceived as genuine. If an “employee of the month” award is rotated regardless of performance, high performers may become demotivated. Instrumentality depends on transparency and consistency.

To enhance valence, managers must understand what employees value. Not all rewards are equally motivating—some may prefer time off, others financial incentives, and still others public recognition. Surveys, conversations, and offering choices can help tailor rewards to individual preferences. When employees see that rewards are meaningful and aligned with their values, motivation increases.

Figure 5.10 Ways in Which Managers Can Influence Expectancy, Instrumentality, and Valence

| Expectancy | Instrumentality | Valence |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Reinforcement Theory: Behavior Shaped by Consequences

Reinforcement Theory, rooted in the work of Ivan Pavlov and later expanded by B. F. Skinner, proposes that behavior is shaped by its outcomes (Skinner, 1953). If a behavior is followed by a favorable consequence, it is more likely to be repeated. Conversely, if a behavior is ignored or punished, it becomes less frequent. For example, if an employee stays late to finish a report and is praised or rewarded, they are more likely to repeat that behavior. If the effort goes unnoticed, motivation may decline.

This principle is observable from infancy. Children quickly learn which actions lead to pleasant outcomes and which result in discomfort. In the workplace, however, reinforcement is often misapplied. Positive behaviors may be ignored, while negative behaviors are inadvertently rewarded. Managers may avoid confronting disruptive employees or reward poor performers simply to relocate them. This misalignment—what Kerr (1995) called “the folly of rewarding A while hoping for B”—can undermine organizational goals.

Four Reinforcement Strategies

Reinforcement theory identifies four key interventions to shape behavior (Beatty & Schneier, 1975):

- Positive Reinforcement: Adding a desirable consequence to encourage behavior (e.g., praise, bonuses).

- Negative Reinforcement: Removing an unpleasant condition once desired behavior occurs (e.g., stopping reminders after task completion).

- Extinction: Eliminating rewards that sustain unwanted behavior (e.g., ignoring disruptive jokes).

- Punishment: Applying negative consequences to discourage behavior (e.g., formal warnings).

Each strategy can be effective, but must be applied thoughtfully. For instance, negative reinforcement may backfire if employees avoid managers to escape nagging.

Figure 5.11 Reinforcement Methods

| Positive Reinforcement | Negative Reinforcement |

|---|---|

| Positive behavior followed by positive consequences (Manager praises the employee) | Positive behavior followed by removal of negative consequences (Manager stops nagging the employee) |

| Punishment | Extinction |

| Negative behavior followed by negative consequences (Manager demotes the employee) | Negative behavior followed by removal of positive consequences (Manager ignores the behavior) |

Reinforcement Schedules

The timing and frequency of reinforcement also matter:

- Continuous Schedule: Reinforcement follows every instance of behavior (e.g., commission per sale). This produces quick results but may not last.

- Fixed-Ratio Schedule: Rewards are given after a set number of behaviors (e.g., bonus every 10 sales).

- Variable-Ratio Schedule: Reinforcement occurs unpredictably (e.g., occasional praise). This produces more durable behavior change.

Research suggests that while variable schedules sustain behavior longer, continuous schedules may yield higher performance in the short term (Cherrington & Cerrington, 1974; Saari & Latham, 1982; Yukl & Latham, 1975).

Workplace Strategy Pack

Fair and Effective Use of Discipline by Supervisors

Purpose: To guide supervisors in applying disciplinary measures that are both fair and effective, using principles from organizational communication and justice theory.

Why Discipline Must Be Fair and Effective

Discipline is not just about correcting behavior—it’s about reinforcing standards, maintaining morale, and promoting organizational effectiveness. Research shows that when disciplinary actions are perceived as fair, employees are more likely to accept them, learn from them, and remain engaged (Dzimbiri, 2016). Unfair or inconsistent discipline, on the other hand, breeds resentment, disengagement, and turnover.

Principles of Fair Discipline

Based on organizational justice and communication research, fair discipline should reflect:

- Consistency: Apply rules uniformly across all employees

- Transparency: Clearly communicate expectations and consequences

- Respect: Treat employees with dignity during disciplinary conversations

- Timeliness: Address issues promptly to prevent escalation

- Documentation: Keep accurate records to ensure accountability

- Constructiveness: Frame discipline as an opportunity for growth, not punishment

Supervisor Strategies for Fair Discipline

| Strategy | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Use Progressive Discipline | Start with verbal warnings, escalate only if needed | Verbal → Written → Suspension → Termination |

| Communicate Expectations Clearly | Ensure employees understand rules and consequences | Share updated policy handbook and review in meetings |

| Hold Private Conversations | Avoid public shaming or embarrassment | Schedule one-on-one meetings for disciplinary discussions |

| Listen Before Acting | Allow employees to explain their side | Use open-ended questions to understand context |

| Avoid Bias | Base decisions on behavior, not personality | Use objective performance data |

| Follow Up | Monitor improvement and offer support | Set goals and check in regularly after discipline |

“Discipline should be a dialogue, not a monologue. Employees are more receptive when they feel heard and respected.” — Inspired by Keyton (2017)

References

Dzimbiri, G. (2016). The effectiveness, fairness and consistency of disciplinary actions and procedures within Malawi: The case of the civil service. IOSR Journal of Business and Management, 18(10), 40–48. https://www.iosrjournals.org/iosr-jbm/papers/Vol18-issue10/Version-2/F1810024048.pdf

Choudhary, S., & Rana, V. (2023). A study on effective employee discipline management in organizations. International Journal of Innovative Research in Technology, 10(1), 1–7. https://ijirt.org/publishedpaper/IJIRT157196_PAPER.pdf

Keyton, J. (2017). Communication in organizations. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 4, 501–526. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/315501844_Communication_in_Organizations

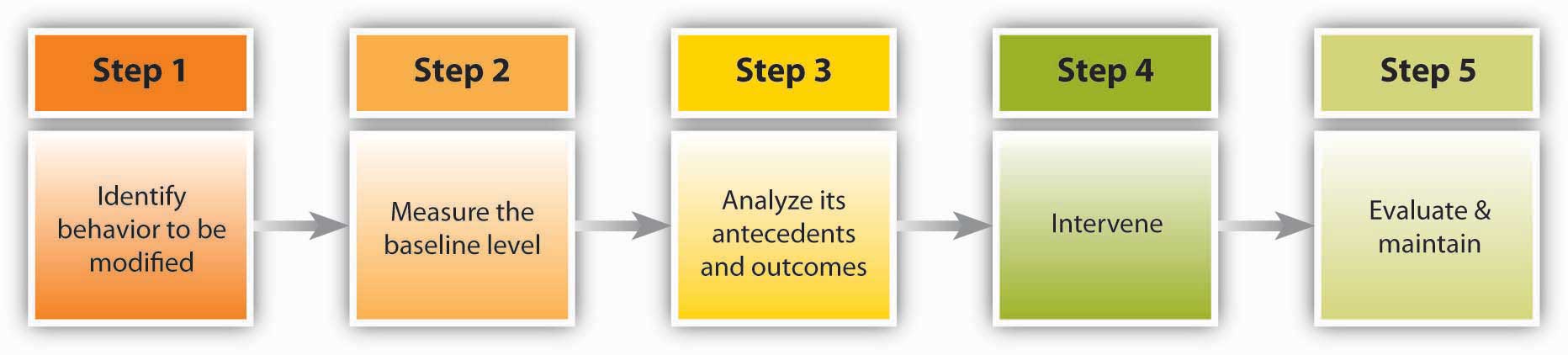

Organizational Behavior Modification (OB Mod)

OB Mod is a structured application of reinforcement theory in the workplace (Luthans & Stajkovic, 1999). It involves five steps:

- Identify the behavior to be changed (e.g., absenteeism).

- Measure baseline frequency of the behavior.

- Analyze antecedents and consequences—what triggers and reinforces the behavior.

- Implement an intervention, such as removing rewards for absenteeism or adding incentives for attendance.

- Monitor and maintain the behavior change over time.

Meta-analyses show OB Mod can improve performance by an average of 17%, especially in manufacturing and service settings (Stajkovic & Luthans, 1997).

Figure 5.12 Stages of Organizational Behavior Modification

Source: Based on information presented in Stajkovic, A. D., & Luthans, F. (1997). A meta-analysis of the effects of organizational behavior modification on task performance, 1975–1995. Academy of Management Journal, 40, 1122–1149.

Discussion Questions

- Your manager tells you that the best way of ensuring fairness in reward distribution is to keep pay a secret. How would you respond to this assertion? Reflect on the role of transparency in fostering perceptions of fairness. Consider how secrecy might undermine trust and distributive justice, and propose alternative approaches to ensure fairness while maintaining confidentiality where necessary.

- When distributing bonuses or pay, how would you ensure perceptions of fairness? Discuss strategies to enhance distributive, procedural, and interactional justice. For example, explain how linking rewards to performance, providing clear criteria for decisions, and communicating decisions respectfully can improve fairness perceptions.

- What are the differences between procedural, interactional, and distributive justice? How could you increase each of these justice perceptions? Define each type of justice and provide actionable examples. For instance, procedural justice can be improved by involving employees in decision-making, interactional justice by treating employees with respect, and distributive justice by ensuring equitable reward distribution.

- Using examples, explain the concepts of expectancy, instrumentality, and valence. Provide a scenario (e.g., a sales target) and break it down into the three components. For example, explain how an employee’s belief in their ability to meet the target (expectancy), the connection between performance and rewards (instrumentality), and the value of the reward (valence) influence motivation.

- Some practitioners and researchers consider OB Mod unethical because it may be viewed as a way of manipulation. What would be your reaction to such a criticism? Evaluate the ethical concerns surrounding OB Mod. Discuss how its application can be ethical if it respects employee autonomy, aligns with organizational goals, and avoids coercion. Provide examples of ethical versus unethical uses of OB Mod.

Section 5.4: The Role of Ethics and National Culture

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter you should be able to do the following:

- Consider the role of motivation for ethical behavior.

- Consider the role of national culture on motivation theories.

Motivation and Ethics: Reinforcement in Action

Why do individuals sometimes behave unethically at work? Motivation theories offer insight into this question, particularly reinforcement theory, which suggests that behavior—ethical or unethical—is shaped by its consequences (Skinner, 1953). If unethical actions are followed by rewards, they are more likely to be repeated. Conversely, if they are punished, they are less likely to recur.

In a simulation study, participants acting as sales managers were informed that their subordinates were offering kickbacks to customers. Those who faced the threat of punishment were more likely to stop the kickbacks, while those who profited from them were more likely to continue the behavior (Hegarty & Sims, 1978). Another study found that both the severity and likelihood of punishment were strong predictors of ethical behavior (Rettig & Rawson, 1963).

Unfortunately, many organizations inadvertently reinforce unethical behavior. Employees may receive promotions or bonuses for meeting aggressive sales targets—even if those results were achieved through questionable means. For example, hotel staff may receive kickbacks from local businesses for customer referrals (Elliott, 2007), and salespeople may push products they don’t believe in to earn spiffs (Radin & Predmore, 2002). To reduce unethical behavior, organizations must remove rewards that follow unethical actions and increase the visibility and certainty of punishment.

Motivation in Cross-Cultural Communication

Motivation is not universal—it’s shaped by cultural values and norms. Most motivation theories, including Maslow’s hierarchy, were developed in Western contexts and may not fully apply across cultures.

For instance, Maslow’s hierarchy of needs assumes a fixed order of needs, but research shows that this order may vary. In a study across 39 countries, financial satisfaction was a stronger predictor of life satisfaction in developing nations, while esteem needs were more influential in industrialized nations (Oishi, Diener, & Suh, 1999).

Fairness is also culturally nuanced. While people everywhere care about justice, their perceptions of fairness and reactions to injustice differ. In low power distance cultures like the United States and Germany, employees value having a voice in decisions and the ability to appeal outcomes. In high power distance cultures such as China and Mexico, interactional justice—being treated with respect—is more highly valued (Brockner et al., 2001; Tata, 2005).

Even the concept of equity in reward distribution varies. In Japan, equality-based rewards are seen as more fair than equity-based ones, which prioritize individual contributions (Kashima et al., 1988). In cultures like India and Japan, need-based or age-based reward systems may be considered more appropriate (Murphy-Berman et al., 1984).

Understanding these cultural differences is essential for designing motivational strategies that resonate globally. Managers must adapt their approaches to align with local values, expectations, and definitions of fairness.

Insider Edge

Motivating Employees Across Global Cultures

In today’s global workplace, motivating employees isn’t a one-size-fits-all endeavor. Cultural values shape how individuals interpret rewards, leadership, and communication. Supervisors and managers must adapt their motivational strategies to reflect these differences—especially in multinational teams or remote global collaborations.

The Cultural Lens on Motivation

Research shows that cultural dimensions such as individualism vs. collectivism, power distance, and uncertainty avoidance significantly influence motivational preferences (Zhao & Pan, 2017; Chen & Kirkman, 2024). For example:

- In individualistic cultures (e.g., U.S., Australia), employees may respond best to personal recognition, autonomy, and performance-based rewards.

- In collectivist cultures (e.g., Japan, Mexico), team-based incentives, group harmony, and relational communication are more effective.

- In high power distance cultures (e.g., India, China), hierarchical respect and formal leadership communication are valued.

- In low power distance cultures (e.g., Denmark, Netherlands), participatory leadership and egalitarian dialogue foster motivation.

Understanding these preferences helps supervisors avoid miscommunication and build trust across cultural boundaries.

Communication Is Key

Organizational communication research emphasizes that how motivation is communicated is just as important as what is offered. Transparent, culturally sensitive messaging enhances perceived fairness and engagement (Kang & Fajardo, 2023). For instance, Western employees may appreciate direct praise, while Eastern employees may prefer subtle acknowledgment that preserves group harmony.

Global teams also benefit from multichannel communication—combining synchronous tools (e.g., Zoom, Teams) with asynchronous platforms (e.g., Slack, email) to accommodate time zones and communication styles (Taras et al., 2021).

Strategies for Cross-Cultural Motivation

| Strategy | Description | Cultural Fit |

|---|---|---|

| Tailor Rewards | Customize incentives to reflect cultural values | Individual bonuses vs. team recognition |

| Use Inclusive Language | Avoid idioms or jargon that may confuse non-native speakers | Global clarity and respect |

| Encourage Dialogue | Invite feedback and questions to build trust | Low power distance cultures |

| Respect Hierarchies | Acknowledge formal roles and titles | High power distance cultures |

| Celebrate Diversity | Recognize cultural holidays and practices | Builds belonging and morale |

Leadership Insight

“Motivation across cultures requires curiosity, humility, and adaptability. The best leaders listen before they lead.” — Inspired by Chen & Kirkman (2024)

References

Chen, G., & Kirkman, B. L. (2024). The study of work motivation across cultures: A review and directions for future research. In The Oxford Handbook of Cross-Cultural Organizational Behavior (pp. 161–182). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190085384.013.7

Kang, M., & Fajardo, O. K. (2023, July 20). What does “fairness” mean to employees? New tools for evaluating internal communication. Institute for Public Relations. https://instituteforpr.org/what-does-fairness-mean-to-employees-new-tools-for-evaluating-internal-communication/

Taras, V., Baack, D., Caprar, D., Jiménez, A., & Froese, F. (2021, June 9). Research: How cultural differences can impact global teams. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2021/06/research-how-cultural-differences-can-impact-global-teams

Zhao, B., & Pan, Y. (2017). Cross-cultural employee motivation in international companies. Journal of Human Resource and Sustainability Studies, 5(4), 215–222. https://doi.org/10.4236/jhrss.2017.54019

Discussion Questions

- What is the connection between a company’s reward system and the level of ethical behaviors? Reflect on how reinforcement theory explains the relationship between rewards and ethical behavior. Discuss how positive consequences can unintentionally reinforce unethical actions and how removing rewards for unethical behavior, while increasing the likelihood and severity of punishment, can promote ethical conduct.

- Which of the motivation theories do you think would be more applicable to many different cultures? Consider the cultural nuances of motivation theories, such as Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, expectancy theory, and reinforcement theory. Evaluate which theory might be most adaptable across cultures and explain your reasoning, using examples of how cultural values influence motivation.

Section 5.5: Spotlight

Motivating Through Mission: St. Louis Children’s Hospital

St. Louis Children’s Hospital (SLCH) exemplifies how organizational communication can be used to foster motivation, ethical behavior, and high performance in a healthcare setting. At SLCH, motivation is not just a managerial tool—it is embedded in the hospital’s mission to “do what’s right for kids.” This purpose-driven communication strategy creates a strong sense of intrinsic motivation among employees, particularly in emotionally demanding roles. The hospital’s 2023 Annual Report noted a 30% decrease in RN turnover, attributing this success to enhanced engagement and a supportive work environment (St. Louis Children’s Hospital, 2023). Such outcomes reflect the power of mission-aligned messaging in shaping employee attitudes and behaviors.

SLCH addresses employee needs across multiple levels of Maslow’s Hierarchy. Physiological and safety needs are met through competitive pay, comprehensive benefits, and secure facilities. Belonging and esteem are supported through civility training, peer support programs, and recognition initiatives. Self-actualization is encouraged through leadership development, quality improvement projects, and opportunities for professional growth (St. Louis Children’s Hospital, 2023). These needs are communicated through internal newsletters, team huddles, and leadership rounding, reinforcing a culture of care and development.

Fairness and justice are central to SLCH’s communication strategy. The hospital maintains transparency through clearly defined policies, such as its Disruptive Behavior Policy and Patient Rights and Responsibilities framework, which outline expectations for respectful conduct and equitable treatment (St. Louis Children’s Hospital, 2025). Superior-subordinate relationships are strengthened through open-door leadership practices and structured feedback channels. These efforts align with Equity Theory, which emphasizes the importance of perceived fairness in shaping employee motivation and satisfaction (Greenberg, 1990).

SLCH primarily uses positive reinforcement to motivate employees. Recognition programs, peer shout-outs, and wellness incentives are common tools for reinforcing desired behaviors. The hospital also offers resilience training, meditation sessions, and emotional support resources to help staff manage stress and maintain performance (Children’s Hospital Association, 2024). While punitive measures are rarely emphasized, the hospital maintains clear accountability structures to address misconduct, ensuring procedural justice and reinforcing ethical standards.

Motivational theories such as Herzberg’s Two-Factor Theory and Self-Determination Theory are evident in SLCH’s approach. Hygiene factors like pay and safety are well-managed, while motivators such as purpose, autonomy, and mastery are actively cultivated. The hospital’s emphasis on team-based care and professional development supports autonomy and competence—two pillars of Self-Determination Theory (Deci & Ryan, 2000). These strategies are communicated through onboarding, ongoing training, and leadership messaging, reinforcing a culture of continuous improvement.

Finally, SLCH’s ethical foundation is supported by its Medical Ethics Subcommittee, which provides staff with resources and guidance for navigating complex decisions (St. Louis Children’s Hospital, 2025). Ethical behavior is not only expected but modeled and reinforced through communication that emphasizes compassion, respect, and accountability. This ethical clarity enhances trust, psychological safety, and long-term motivation—making SLCH a model for how organizational communication can drive both performance and purpose.

References

Children’s Hospital Association. (2024). Retention: Empower your employees. https://www.childrenshospitals.org/content/topics/solutions-for-a-sustainable-workforce/retention

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227–268.

Greenberg, J. (1990). Organizational justice: Yesterday, today, and tomorrow. Journal of Management, 16(2), 399–432.

St. Louis Children’s Hospital. (2023). 2023 Annual Report. https://www.stlouischildrens.org/sites/legacy/files/1700500_SLCH_Nursing-Annual-Report-FINAL%20%281%29_0.pdf

St. Louis Children’s Hospital. (2025). Ethics resources for staff. https://www.stlouischildrens.org/healthcare-professionals/medical-ethics-subcommittee/ethics-resources-for-staff

St. Louis Children’s Hospital. (2025). Patient rights and responsibilities. https://www.stlouischildrens.org/visit-us/patient-rights-responsibilities

Discussion Questions

- How does effective organizational communication at St. Louis Children’s Hospital enhance employee motivation and, in turn, improve performance? What specific communication strategies might help employees connect their daily tasks to the hospital’s mission of “doing what’s right for kids”?

- How does St. Louis Children’s Hospital use communication to identify and address the basic needs of its employees? In what ways does the hospital ensure that these needs—ranging from safety to self-actualization—are consistently met across different roles?

- How does St. Louis Children’s Hospital maintain a positive perception of fairness among employees through its communication practices? How are rewards and consequences communicated to ensure transparency and alignment with the hospital’s values?

- Which motivation theories (e.g., Herzberg’s Two-Factor Theory, Self-Determination Theory) are most evident in St. Louis Children’s Hospital’s communication strategies? How does the hospital use forms of reinforcement, such as recognition programs or wellness initiatives, to sustain employee motivation while upholding its ethical standards?

Section 5.6: Conclusion

In this chapter, we explored foundational theories of motivation that help explain why individuals engage in goal-directed behavior at work. Some theories emphasize the role of internal needs, suggesting that employees are motivated by efforts to satisfy physiological, social, and psychological desires. From this perspective, managers can enhance motivation by identifying and addressing the specific needs that drive employee behavior. Other theories focus on cognitive processes, highlighting how employees evaluate fairness, learn from the consequences of their actions, and assess whether their efforts will lead to meaningful rewards. For example, employees may disengage when they perceive inequity, repeat behaviors that yield positive outcomes, and invest effort when they believe it will result in valued rewards. While no single theory offers a complete explanation of motivation, each provides a useful lens for analyzing, interpreting, and managing employee behavior. Together, these frameworks equip managers with practical tools to foster engagement, performance, and satisfaction in diverse workplace settings.

5.7 Case Study and Exercises

Ethical Dilemma Case Study

The Commuter’s Choice

Jordan is a 20-year-old sophomore majoring in organizational communication at a metropolitan university. As a commuter student, Jordan balances a part-time job at a local marketing firm with a full course load. The firm is small but growing, and Jordan was hired as a communications assistant to help with internal messaging and social media outreach.

Jordan’s manager, Ms. Pately, recently introduced a new incentive program based on performance metrics. Employees who exceed weekly engagement targets on social media receive gift cards and public recognition. While the program has boosted morale for some, Jordan feels conflicted. The metrics don’t account for the time constraints Jordan faces as a student and commuter, and the pressure to perform has led Jordan to consider cutting corners—such as reposting recycled content or inflating engagement numbers.

Jordan is torn between two choices:

- Option A: Continue participating in the incentive program, even if it means compromising authenticity and quality to meet performance goals.

- Option B: Raise concerns with Ms. Pately about the fairness of the program, risking being seen as unmotivated or not a team player.

Jordan wonders whether motivation theories can help explain the dynamics at play—and whether they offer any guidance for navigating this ethical tension.

Some motivation theories offer insight into Jordan’s situation. For example:

- Equity Theory (Adams, 1965): Jordan perceives an imbalance between effort and reward compared to peers who have fewer outside commitments. This perceived inequity may lead to reduced motivation or unethical behavior to restore balance.

- Expectancy Theory (Vroom, 1964): Jordan questions whether effort will lead to meaningful rewards, especially when external constraints (school, commuting) limit performance.

Discussion Questions

- How might Jordan’s status as a commuting student influence their motivation and ethical decision-making?

- What communication strategies could Jordan use to express concerns without damaging workplace relationships?

- How can managers design incentive programs that account for diverse employee circumstances?

References

- Adams, J. S. (1965). Inequity in social exchange. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 2, 267–299. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2601(08)60108-2

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. Springer.

- Vroom, V. H. (1964). Work and motivation. Wiley.

- Miller, K. (2021). Organizational communication: Approaches and processes (8th ed.). Cengage Learning.

Individual Exercise

Motivation Mapping in My Real Life

Objective

To apply motivational theories to a real-world experience by analyzing one’s own behavior, decisions, and communication in a workplace, volunteer, or academic setting—using personal insight and theory-based reflection.

Instructions

- Choose a Real Experience Select a specific situation from your own life where you felt highly motivated—or deeply unmotivated—in a group or organizational setting. This could be:

- A part-time job

- A group project

- A volunteer role

- A student organization

- Describe the Context Write a 300–500 word narrative describing:

- The setting and your role

- What you were expected to do

- How you felt about the task and environment

- Apply Two Motivation Theories In a separate section, analyze your experience using two distinct motivation theories, such as:

- Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

- Herzberg’s Two-Factor Theory

- Equity Theory

- Expectancy Theory

For each theory:

- Briefly explain the theory in your own words

- Apply it to your experience: What does the theory reveal about why you felt motivated or not?

- Reflect on Communication Conclude with a reflection (200–300 words) on how communication—between you and others—impacted your motivation. Consider:

- Feedback you received

- Recognition or lack thereof

- Clarity of expectations

- Any miscommunication or conflict

References

Abdulhamidova, F. (2021). Herzberg’s Two-Factor Theory: Organizational Communication. ResearchGate. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/352465259_Herzberg’s_Two-Factor_Theory

Adams, J. S. (1965). Inequity in social exchange. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 2, 267–299. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2601(08)60108-2

Alderfer, C. P. (1969). An empirical test of a new theory of human needs. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 4(2), 142–175. https://doi.org/10.1016/0030-5073(69)90004-X

Alge, B. J. (2001). Effects of computer surveillance on perceptions of privacy and procedural justice. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(4), 797–804. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.86.4.797

Arogundade, A. M., & Akpa, V. O. (2023). Alderfer’s ERG and McClelland’s Acquired Needs Theories: Relevance in Today’s Organization. Scholars Journal of Economics, Business and Management, 10(10), 232–239. https://doi.org/10.36347/sjebm.2023.v10i10.001

Austin, W., & Walster, E. (1974). Reactions to confirmations and disconfirmations of expectancies of equity and inequity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 30(2), 208–216. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0036622

Baptista, J. A. de A., Formigoni, A., Silva, S. A. da, Stettiner, C. F., & Novais, R. A. B. de. (2023). Analysis of the Theory of Acquired Needs from McClelland as a Means of Work Satisfaction. TLJBM Journal. https://tljbm.org/jurnal/index.php/tljbm/article/download/48/37/

Bauer, T. N., Maertz, C. P., Dolen, M. R., & Campion, M. A. (1998). Longitudinal assessment of applicant reactions to employment testing and test outcome feedback. Journal of Applied Psychology, 83(6), 892–903. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.83.6.892

Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117(3), 497–529. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.497

Beatty, R. W., & Schneier, C. E. (1975). A critique of reinforcement theory in organizational settings. Journal of Management, 1(2), 25–41. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920637500100204

Blader, S. L. (2007). What leads organizational members to collectivize? Injustice and identification as precursors of union certification. Organization Science, 18(1), 108–126. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1060.0220

Brockner, J., & Wiesenfeld, B. M. (1996). An integrative framework for explaining reactions to decisions. Psychological Bulletin, 120(2), 189–208. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.120.2.189

Brockner, J., Ackerman, G., Greenberg, J., Gelfand, M. J., Francesco, A. M., Chen, Z. X., … & Shapiro, D. (2001). Culture and procedural justice: The influence of power distance on reactions to voice. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 37(4), 300–315. https://doi.org/10.1006/jesp.2000.1451

Campbell, D. J. (1982). Determinants of choice of goal difficulty. Academy of Management Review, 7(4), 479–486. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1982.4285351

Carrell, M. R., & Dittrich, J. E. (1978). Equity theory: The recent literature, methodological considerations, and new directions. Academy of Management Review, 3(2), 202–210. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1978.4294844

Caulton, J. R. (2020). The development and use of the theory of ERG: A literature review. Emerging Leadership Journeys, 5(1), 2–8. Regent University PDF

Cherrington, D. J., & Cerrington, J. O. (1974). The effect of reinforcement schedules on performance in organizational settings. Journal of Applied Psychology, 59(4), 496–500. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0037332

Cohen-Charash, Y., & Spector, P. E. (2001). The role of justice in organizations: A meta-analysis. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 86(2), 278–321. https://doi.org/10.1006/obhd.2001.2958

Colquitt, J. A., Conlon, D. E., Wesson, M. J., Porter, C. O., & Ng, K. Y. (2001). Justice at the millennium: A meta-analytic review of 25 years of organizational justice research. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(3), 425–445. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.86.3.425

Cook, C. W. (1980). Guidelines for managing motivation. Business Horizons, 23(3), 61–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/0007-6813(80)90040-2

Creed, A., Zutshi, A., & Baker, M. (2025). How existence-relatedness-growth (ERG) can encourage collaboration between departments beyond formal structure. The European Business Review. https://www.europeanbusinessreview.com/how-existence-relatedness-growth-erg-can-encourage-collaboration-between-departments-beyond-formal-structure/

Cropanzano, R., Bowen, D. E., & Gilliland, S. W. (2007). The management of organizational justice. Academy of Management Perspectives, 21(4), 34–48. https://doi.org/10.5465/amp.2007.27895338

Cummings, L. L., & Elsalmi, A. M. (1968). Empirical research on the Herzberg hypothesis: A critique. Personnel Psychology, 21(3), 335–350. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.1968.tb00158.x

Elliott, C. (2007, March 4). The concierge economy. New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2007/03/04/travel/04praccon.html

Erdogan, B., & Liden, R. C. (2006). Collectivism as a moderator of responses to organizational justice: Implications for leader-member exchange and ingratiation. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 27(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.365

Evan, W. M., & Simmons, R. G. (1969). Organizational effects of inequitable rewards: Two experiments in status inconsistency. Administrative Science Quarterly, 14(2), 224–237. https://doi.org/10.2307/2391121

Fripp, G. (n.d.). What is Equity Theory?. MyOrganisationalBehaviour.com

Goodman, P. S., & Friedman, A. (1971). An examination of Adams’s theory of inequity. Administrative Science Quarterly, 16(3), 271–288. https://doi.org/10.2307/2391908

Greenberg, J. (1993). Stealing in the name of justice: Informational and interpersonal moderators of theft reactions to underpayment inequity. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 54(1), 81–103. https://doi.org/10.1006/obhd.1993.1004

Greenberg, J. (2004). Managing workplace stress by promoting organizational justice. Organizational Dynamics, 33(4), 352–365. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orgdyn.2004.09.003

Greenberg, J. (2006). Losing sleep over organizational injustice: Attenuating insomniac reactions to underpayment inequity with supervisory training in interactional justice. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91(1), 58–69. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.91.1.58

Harrell, T. W., & Stahl, M. J. (1981). Traits of successful entrepreneurs. Journal of Creative Behavior, 15(3), 178–184. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2162-6057.1981.tb00287.x

Harvey, M. G., & Sims, H. P. (1978). Effects of reinforcement contingencies on unethical behavior. Journal of Applied Psychology, 63(3), 331–337. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.63.3.331

Hegarty, W. H., & Sims, H. P. (1978). Some determinants of unethical decision behavior: An experiment. Journal of Applied Psychology, 63(4), 451–457. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.63.4.451

Heneman, H. G., & Schwab, D. P. (1972). Evaluation of expectancy theory predictions of employee performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 56(6), 398–403. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0033873

Herzberg, F. (1965). Work and the nature of man. World Publishing.

Herzberg, F., Mausner, B., & Snyderman, B. B. (1959). The motivation to work (2nd ed.). Wiley.

House, R. J., & Wigdor, L. A. (1967). Herzberg’s dual-factor theory of job satisfaction and motivation: A review of the evidence and a criticism. Personnel Psychology, 20(4), 369–390. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.1967.tb02440.x

HRDQ. (n.d.). Adam’s Equity Theory of Motivation in the Workplace – Explained. HRDQ Blog

Huseman, R. C., Hatfield, J. D., & Miles, E. W. (1987). A new perspective on equity theory: The equity sensitivity construct. Academy of Management Review, 12(2), 222–234. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1987.4307921

Indeed Editorial Team. (2025). A Guide to Equity Theory of Motivation. Indeed.com

Ivancevich, J. M., Konopaske, R., & Matteson, M. T. (2008). Organizational behavior and management (8th ed.). McGraw-Hill Education.

Kashima, Y., Siegal, M., Tanaka, K., & Kashima, E. S. (1988). Do people believe in distributive justice? A cross-cultural study. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 19(1), 62–77. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022188191005

Kerr, S. (1995). On the folly of rewarding A, while hoping for B. Academy of Management Executive, 9(1), 7–14. https://doi.org/10.5465/ame.1995.9503133492

Kidwell, R. E. (1995). Pink slips without tears. Academy of Management Executive, 9(1), 69–70. https://doi.org/10.5465/ame.1995.9503133492

Kurt, S. (2023). Equity Theory: Definition, Origins, Components and Examples. Education Library.

Luthans, F., & Stajkovic, A. D. (1999). Reinforce for performance: The need to go beyond pay and even rewards. Academy of Management Executive, 13(2), 49–57. https://doi.org/10.5465/ame.1999.1899548

Maslow, A. H. (1943). A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review, 50(4), 370–396. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0054346

Maslow, A. H. (1954). Motivation and personality. Harper & Row.

McClelland, D. C. (1961). The achieving society. Princeton, NJ: Van Nostrand.

McClelland, D. C., & Boyatzis, R. E. (1982). Leadership motive pattern and long-term success in management. Journal of Applied Psychology, 67(6), 737–743. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.67.6.737

McClelland, D. C., & Burnham, D. H. (1976). Power is the great motivator. Harvard Business Review, 54(2), 100–110.

Mitchell, T. R. (1982). Motivation: New directions for theory, research, and practice. Academy of Management Review, 7, 80–88.

Mitsakis, M., & Galanakis, M. (2022). An empirical examination of Herzberg’s theory in the 21st-century workplace. Psychology, 13(2), 264–272. https://doi.org/10.4236/psych.2022.132015

Mueller, C. M., & Dweck, C. S. (1998). Praise for intelligence can undermine children’s motivation and performance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75(1), 33–52. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.75.1.33

Mueller, J., & Wynn, P. (2000). The degree of justice in pay systems: A cross-national comparison. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 11(4), 785–806. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585190050075180

Murphy-Berman, V., Berman, J. J., Singh, P., Pachauri, A., & Kumar, P. (1984). Cultural differences in perceptions of distributive justice. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 15(1), 67–77. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002184015001006

Neher, A. (1991). Maslow’s theory of motivation: A critique. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 31(3), 89–112. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022167891313010

Nickerson, C. (2025). Herzberg’s Two-Factor Theory of Motivation-Hygiene. Simply Psychology. https://www.simplypsychology.org/herzbergs-two-factor-theory.html