Chapter 10: From Tension to Trust: A Peacemaker’s Guide to Conflict

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, you should be able todo the following:

- Identify and differentiate between various types of conflict in organizational settings.

- Analyze the underlying causes of conflict within teams and organizations.

- Evaluate the short- and long-term consequences of unresolved and poorly managed conflict.

- Apply effective conflict management strategies to resolve interpersonal and group disputes.

- Describe and illustrate the key stages of the negotiation process.

- Recognize and avoid common negotiation errors through strategic preparation and reflection.

- Demonstrate ethical decision-making in conflict resolution and negotiation scenarios.

- Compare and assess cross-cultural differences in conflict styles and negotiation approaches.

Section 10.1: Spotlighht

Communication Breakdown: The 2015 University of Missouri Conflict

In 2015, the University of Missouri (Mizzou) became a national focal point for racial tensions and administrative accountability. The conflict began with student reports of racial slurs and symbols of hate, including a swastika drawn in feces in a residence hall. These incidents, combined with what students perceived as administrative inaction, escalated into a full-blown organizational crisis. The types of conflict involved were both interpersonal—between students and administrators—and structural, rooted in systemic issues of race, representation, and institutional responsiveness. The situation also reflected value-based conflict, as students and leadership clashed over the university’s commitment to diversity and inclusion.

The university’s failure to manage the conflict effectively stemmed largely from communication breakdowns. President Tim Wolfe’s delayed and vague responses to student concerns were interpreted as dismissive, fueling further unrest. According to organizational communication theory, timely, transparent, and empathetic messaging is critical during crises (Clampitt, 2016). Instead, the administration’s lack of visible engagement created a vacuum that student activists filled with protests, a hunger strike, and eventually a football team boycott. These actions forced the administration into reactive rather than proactive communication, undermining trust and credibility.

The negotiation process between students and university leadership was marked by missteps. Wolfe’s refusal to meet early demands for dialogue and his failure to acknowledge the emotional weight of the students’ experiences created a perception of indifference. Negotiation theory emphasizes the importance of active listening and mutual respect in resolving disputes (Fisher & Ury, 2011). By not engaging in meaningful dialogue until the crisis reached a boiling point, the administration missed opportunities to de-escalate tensions and co-create solutions with student leaders.

Cross-cultural differences in conflict management further complicated the situation. Many of the protesting students were Black, while the university’s leadership was predominantly white. Research shows that cultural backgrounds influence how individuals perceive and respond to conflict—some cultures value direct confrontation, while others prefer indirect or collaborative approaches (Avruch, 1998). The administration’s formal, bureaucratic responses may have clashed with students’ expectations for personal acknowledgment and emotional validation, exacerbating feelings of marginalization.

The consequences of the conflict were profound. President Wolfe and Chancellor R. Bowen Loftin both resigned, and the university faced national scrutiny, enrollment declines, and reputational damage. In response, Mizzou implemented structural changes, including the creation of a Chief Diversity, Inclusion, and Equity Officer and mandatory diversity training. These outcomes underscore the importance of organizational communication in crisis management. When communication fails to reflect empathy, transparency, and cultural awareness, even isolated incidents can spiral into institutional crises.

Ultimately, the University of Missouri’s 2015 conflict serves as a cautionary tale about the cost of communication failures in diverse, high-stakes environments. It highlights the need for leaders to engage in culturally competent dialogue, respond swiftly to emerging tensions, and foster inclusive communication channels that empower all voices within the organization.

References

Avruch, K. (1998). Culture and conflict resolution. United States Institute of Peace Press.

Clampitt, P. G. (2016). Communicating for managerial effectiveness: Challenges, strategies, solutions (6th ed.). SAGE Publications.

Fisher, R., & Ury, W. (2011). Getting to yes: Negotiating agreement without giving in (3rd ed.). Penguin Books.

University of Missouri. (2015). Campus climate updates and diversity initiatives. https://missouri.edu

Discussion Questions

- How could the University of Missouri’s leadership have applied more effective communication strategies early in the conflict to prevent escalation, particularly in responding to value-based and structural conflicts?

- In what ways might cross-cultural communication styles have influenced the breakdown in dialogue between students and university leadership, and how can understanding these differences improve future negotiation efforts in diverse environments?

- What role does leadership visibility and empathetic listening play in conflict resolution within large institutions, and how might earlier engagement from President Wolfe have changed the negotiation dynamic and outcome?

Section 10.2: Understanding Conflict

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, you should be able to do the following:

- Define and distinguish between five types of organizational conflict—intrapersonal, interpersonal, intragroup, intergroup, and interorganizational—and articulate their key characteristics and implications.

- Evaluate the impact of conflict levels on team performance by interpreting research on task, relationship, and process conflict across project lifecycles.

- Analyze the potential benefits of moderate task-related conflict, including its role in fostering creativity, improving decision-making, and enhancing team dynamics.

- Identify root causes of workplace conflict, such as miscommunication, structural tensions, or competing goals, and link these causes to specific types of conflict.

- Differentiate between constructive and destructive conflict behaviors, using real-world examples (e.g., Intel’s “constructive confrontation” training) to illustrate conflict management strategies.

- Apply rhetorical and emotional intelligence principles to conflict resolution, such as face-saving techniques, non-defensive dialogue, and inclusive communication.

- Reflect on personal conflict experiences in the workplace and assess how context, communication style, and conflict type influenced the outcomes.

Conflict is a natural and inevitable part of organizational life, arising when individuals or groups perceive incompatible goals, limited resources, or interference in achieving their objectives (De Dreu & Beersma, 2005). Rather than viewing conflict as inherently negative, contemporary organizational communication research encourages us to see it as a potential catalyst for growth, innovation, and deeper understanding—especially when approached with humility and ethical awareness. This chapter reframes conflict not as a disruption to avoid, but as an opportunity to practice emotional intelligence, relational repair, and peacemaking.

Scholars typically classify conflict into three foundational types: intrapersonal, interpersonal, and intergroup (Lumen Learning, n.d.; Rice, 2000). Intrapersonal conflict occurs within the individual and often involves competing roles, values, or decisions. For example, an employee may struggle between loyalty to a supervisor and solidarity with peers. Peacemaking in this context involves acknowledging internal tension and resisting binary thinking, recognizing that multiple truths may coexist (Gladwell, 2013). Interpersonal conflict arises between individuals—such as coworkers or managers and subordinates—and often stems from miscommunication, personality differences, or perceived power imbalances. A peacemaker avoids assuming motives and recognizes personal bias, engaging in dialogue that prioritizes dignity and mutual respect (DeAngelis, 2010). Intergroup conflict occurs between teams, departments, or organizations and often reflects deeper issues related to competition, cultural divides, or resource allocation. Peacemakers in these situations resist “us vs. them” mentalities and apply uplifting directives to foster collaboration and shared purpose (Ahmed, 2021).

Importantly, conflict is not always harmful. Research distinguishes between task-related conflict—which can enhance decision-making and creativity—and relationship conflict, which tends to be more emotionally charged and destructive (Rispens, 2014). When managed ethically, moderate levels of task conflict can improve team performance and problem-solving. However, unresolved relationship conflict can erode trust and psychological safety. Peacemakers navigate these tensions by practicing apology and forgiveness, staying open to multiple perspectives, and resisting the urge to “die on the hill of rightness.” The goal is not to eliminate conflict, but to transform it into trust, clarity, and shared direction.

4 Types of Conflict in Organizations

Intrapersonal Conflict

Intrapersonal conflict occurs within the individual and often involves competing values, roles, or psychological pressures. For example, an employee may experience tension between personal beliefs and professional responsibilities, leading to ethical dilemmas or decision paralysis. This form of conflict is often invisible to others but can significantly affect motivation and clarity (Elmoudden, 2023; Kahn, Wolfe, Quinn, Snoek, & Rosenthal, 1964). Peacemaking in intrapersonal conflict requires introspection, recognition of bias, and emotional regulation—practices that foster resilience and growth rather than avoidance (Lewin, 1948).

Interpersonal Conflict

Interpersonal conflict emerges between individuals—coworkers, supervisors, or clients. It can stem from personality differences, miscommunication, or perceived disrespect. In organizational life, interpersonal conflict is one of the most frequent and often the most visible types. Emotional intelligence and active listening are critical tools for managing these disputes constructively (Oetzel, Ting-Toomey, Masumoto, & Yokochi, 2003; Tripathy, 2021). The ability to apologize and engage in non-defensive dialogue enhances relationship quality and promotes reconciliation.

Intragroup Conflict

Intragroup conflict arises within a team or department. It may involve disagreements over goals, methods, or role clarity. Not all intragroup conflict is destructive—task-related disagreements, for instance, can lead to deeper understanding and innovation (Jehn, 1995). However, when conflict becomes personal or relational, it threatens cohesion and morale. Inclusive communication and shared purpose are vital in transforming internal rifts into opportunities for growth (McCarter, Fienberg, & Galvin, 2018; Wu & Sekiguchi, 2019).

Intergroup Conflict

Intergroup conflict takes place between distinct groups or units—such as departments with differing priorities. For instance, tension between a hospital’s clinical and administrative branches may originate from role misalignment or competition for resources. While moderate levels of conflict can encourage creativity and sharpen group identity, unmanaged intergroup disputes often reinforce siloed thinking and reduce collaboration (Fisher, 1990; Nicotera & Jameson, 2021). Overcoming these divides requires cross-group dialogue and a shared vision that bridges functional differences.

Interorganizational Conflict

Interorganizational conflict occurs between separate entities such as partners, competitors, or vendors. These conflicts are shaped by structural inequalities, divergent interests, or cultural mismatches. For example, strategic alliances can deteriorate when trust breaks down or objectives shift. Resolving such conflicts demands negotiation, mutual understanding, and often third-party mediation (Lumineau, Fréchet, & Puthod, 2015). Unlike internal disputes, interorganizational conflict often lacks a formal resolution structure, making relational norms and communication protocols especially important (Aldrich, 1971).

When Conflict Fuels Progress: Rethinking the “Bad” Reputation

Many people instinctively shy away from conflict, viewing it as disruptive or emotionally exhausting. But is conflict always bad? While conflict can become harmful when it paralyzes decision-making, diminishes team performance, or escalates into hostility, it can also be a surprisingly constructive force in organizational life (Amason, 1996). The challenge lies in understanding the sources, consequences, and optimal levels of conflict—and in cultivating communication strategies to manage it effectively.

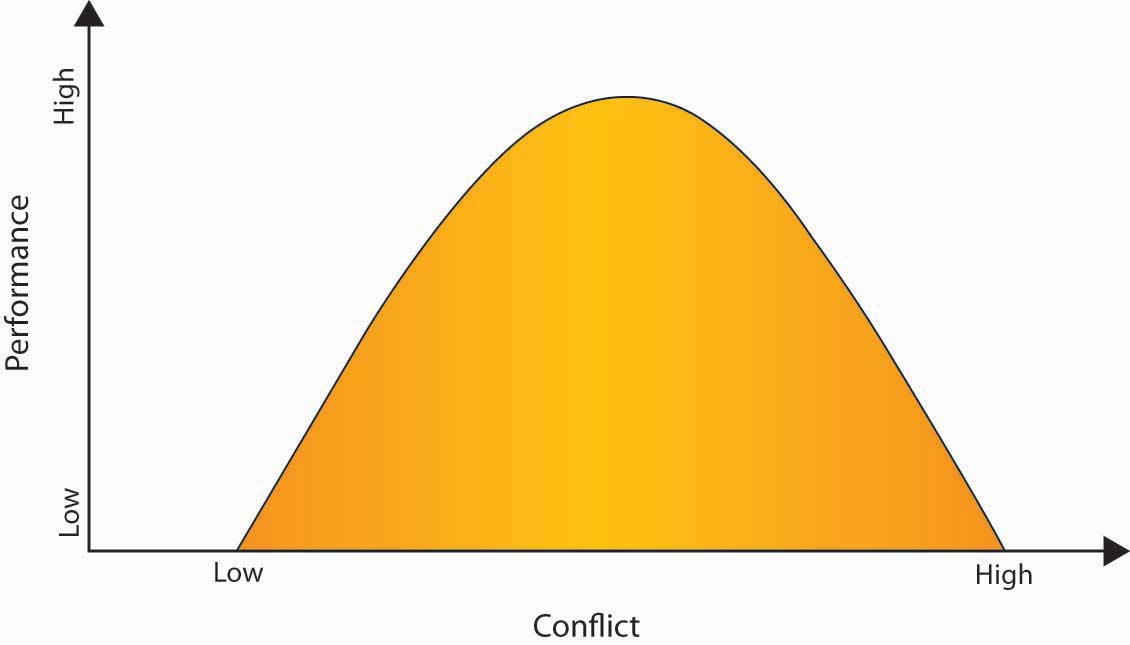

Conflict exists on a continuum, and both extremes carry risk. Too little conflict may signal apathy or groupthink, leading to uninspired ideas and weak performance. Conversely, too much conflict can fracture relationships and hinder collaboration. The sweet spot? A moderate level of task-related conflict—especially in the early phases of decision making—is often ideal, because it sparks healthy debate and invites diverse perspectives (De Dreu & Weingart, 2003). This type of conflict may enhance creativity, encouraging team members to push beyond superficial solutions.

However, not all conflict is created equal. Personal conflicts—such as targeted criticism or emotional outbursts—rarely contribute anything positive. These interactions tend to produce stress, damage trust, and may even result in bullying or workplace toxicity. In contrast, task conflict centers on ideas and solutions, not individuals, and can energize groups without alienating participants.

Organizations that embrace conflict as a tool for growth often provide training to help employees engage productively. Intel Corporation, for example, developed a “constructive confrontation” module for new hires. This four-hour training teaches workers to communicate through facts rather than personal attacks, and to focus discussion on issues—not personalities. “We don’t spend time being defensive or taking things personally. We cut through all of that and get to the issues,” notes a trainer from Intel University (Dahle, 2001). While its long-term impact isn’t fully known, the initiative illustrates a proactive approach to conflict that views it not as something to suppress, but as something to harness.

Research tracking effective teams over time reveals an intriguing pattern: successful teams tend to exhibit low but increasing levels of process conflict—the “how” of getting work done. They experience low relationship conflict, with slight upticks toward project completion, and moderate levels of task conflict midway through their timeline (Jehn & Mannix, 2001). These dynamics suggest that well-managed conflict, aligned with purpose and timing, can drive collaboration and results rather than derail them.

Conflict as Catalyst

Conflict, when mismanaged or left unchecked, can undoubtedly hinder productivity and erode relationships. Yet, as we’ve seen, conflict is not inherently negative—it is a natural and even necessary feature of organizational life. The key is balance. Task-related conflict at moderate levels can drive innovation, sharpen decision-making, and challenge teams to think beyond the obvious. By contrast, personal and relational conflict typically destabilize group dynamics, highlighting the importance of communication training and emotional intelligence.

Recognizing that conflict exists on a continuum empowers leaders and team members to actively manage its presence—not to eliminate it entirely, but to shape its outcomes. Programs like Intel’s “constructive confrontation” suggest that conflict can be taught as a skill, not feared as a threat. As research on effective teams indicates, the timing, type, and intensity of conflict all influence whether it ultimately strengthens or weakens performance.

So rather than asking whether conflict is “bad,” perhaps a better question is: How do we harness conflict as a force for growth, dialogue, and innovation? With the right tools and mindset, conflict becomes less of a problem to avoid—and more of a strategy to embrace.

Insider Edge

Navigating Workplace Sabotage and Conflict-Driven Colleagues

In every organization, collaboration is key—but what happens when a colleague seems to thrive on conflict, manipulation, or subtle sabotage? Whether it’s passive-aggressive emails, strategic obstruction, or public undermining, these behaviors can erode trust, productivity, and morale. This Insider Edge equips you with research-backed strategies to protect your work, maintain professionalism, and foster a healthier communication climate.

Recognizing the BehaviorSabotage and conflict-seeking behaviors often manifest as:

- Relational aggression: Gossip, exclusion, or undermining others’ credibility (Coyne et al., 2006)

- Passive resistance: Withholding information, missing deadlines, or feigning incompetence (Kassing, 2000)

- Toxic competitiveness: Prioritizing personal gain over team success (Ferris et al., 2007)

These behaviors are often rooted in insecurity, power struggles, or a desire for control. Recognizing them is the first step toward neutralizing their impact.

Strategies for Empowerment

1. Document and Clarify

Keep records of interactions that feel manipulative or obstructive. Use clear, assertive language in communication to minimize ambiguity and reduce opportunities for misinterpretation.

Example: “To confirm, you’ll be submitting the report by Friday at noon, correct?”

2. Use Upward Dissent Constructively

Kassing (2000) identifies “articulated dissent” as a healthy way to voice concerns to supervisors. Frame issues around organizational goals rather than personal grievances.

Instead of: “Alex is sabotaging my work.” Try: “I’ve noticed recurring delays that are impacting our team’s deliverables. Can we explore ways to improve coordination?”

3. Build Alliances, Not Cliques

Strengthen relationships with colleagues who value transparency and collaboration. This creates a buffer against toxic dynamics and reinforces a culture of accountability.

4. Leverage Organizational Channels

Use HR, ombudspersons, or anonymous reporting tools when direct resolution isn’t feasible. Organizations with strong ethical climates encourage reporting and protect whistleblowers (Mayer et al., 2009).

5. Practice Communication Resilience

Train yourself to respond—not react. Techniques like reframing, active listening, and boundary-setting help maintain professionalism under pressure (Goleman, 2006).

Culture Shift Starts with You

While you may not be able to change a colleague’s behavior, you can influence the communication climate around you. Modeling ethical, assertive, and transparent communication sets a standard that others often follow.

References

Coyne, I., Seigne, E., & Randall, P. (2006). Predicting workplace victim status from personality. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 15(3), 307–330. https://doi.org/10.1080/13594320600636518

Ferris, G. R., Liden, R. C., Munyon, T. P., Summers, J. K., Basik, K. J., & Buckley, M. R. (2007). Organizational politics: The nature of the construct, a research agenda, and a summary of empirical findings. In C. P. Hulin & W. C. Borman (Eds.), APA handbook of industrial and organizational psychology (Vol. 3, pp. 233–263). American Psychological Association.

Goleman, D. (2006). Social intelligence: The new science of human relationships. Bantam Books.

Kassing, J. W. (2000). Exploring the relationship between dissent-related communication and employee participation in decision-making. Management Communication Quarterly, 14(3), 442–470. https://doi.org/10.1177/0893318900143003

Mayer, D. M., Kuenzi, M., Greenbaum, R., Bardes, M., & Salvador, R. (2009). How low does ethical leadership flow? Test of a trickle-down model. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 108(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2008.04.002

Discussion Questions

- Conflict can arise within oneself, between individuals, and across teams and organizations. Based on what you’ve learned, how would you describe the differences between intrapersonal, interpersonal, intragroup, intergroup, and interorganizational conflicts?

- Organizational conflict may stem from misaligned goals, unclear roles, communication breakdowns, or structural tensions. What do you think are the most common causes of conflict in professional settings?

- Miscommunication can contribute to conflict by distorting intentions, triggering emotional responses, or reinforcing stereotypes. Reflecting on your own experience, how has poor communication played a role in escalating conflict?

Section 10.3: Causes and Outcomes of Conflict

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, you should be able to do the following:

- Identify and analyze common causes of conflict in organizational settings

- Examine occupational factors that increase the risk of workplace conflict and violence

- Evaluate the potential outcomes of workplace conflict—both constructive and harmful

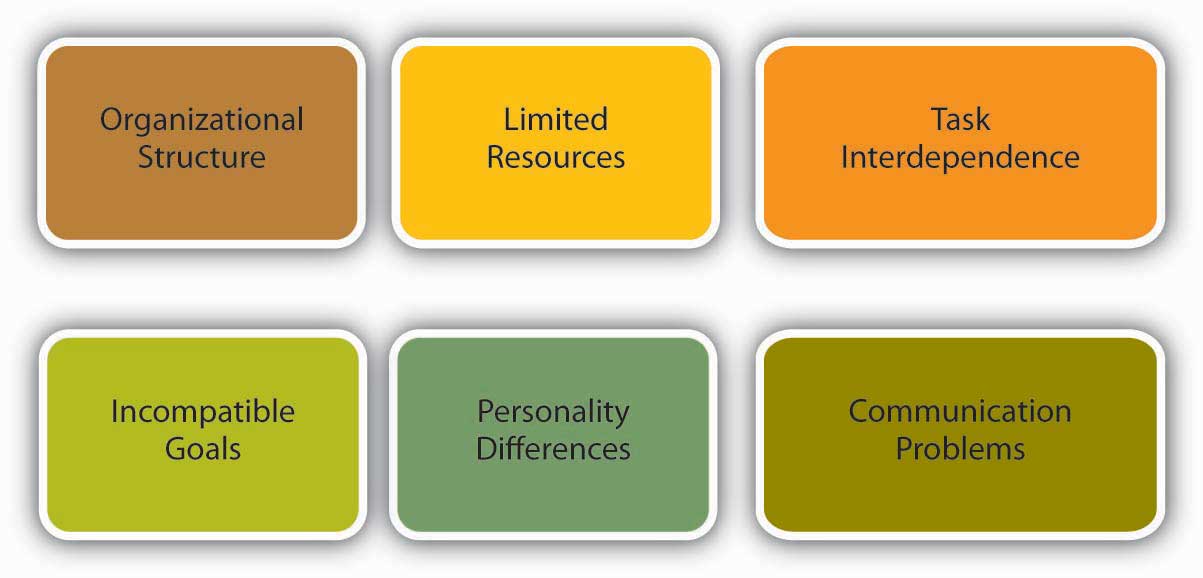

Conflict in organizations rarely arises from a single source; rather, it stems from an interplay of structural, interpersonal, and informational dynamics. One major contributor is organizational structure—hierarchies and formal reporting lines can generate tension by restricting communication, fostering power imbalances, and limiting collaborative autonomy (Elmoudden, 2023). Similarly, limited resources such as time, budget, or personnel may force teams into competitive postures, breeding resentment and friction (Jehn & Mannix, 2001). Task interdependence adds another layer; when projects require tight coordination, one team’s delay or misalignment can negatively impact others, leading to blame and frustration (De Dreu & Weingart, 2003). Incompatible goals also often spark conflict—different departments may pursue divergent objectives, such as marketing pushing for reach while operations emphasize cost efficiency, resulting in persistent tension (Amason, 1996). Personality differences, including distinct temperaments, values, or communication styles, further complicate collaboration and can intensify emotional reactions in high-stakes environments (Tripathy, 2021). Most significantly, miscommunication—including missing or misunderstood information, poor timing, or digital ambiguity—frequently serves as the spark that ignites deeper issues. When teams fail to clarify expectations, intentions can be misread and trust undermined (Oetzel et al., 2003).

The outcomes of conflict are equally multifaceted. Negative consequences can be severe—reduced morale, emotional stress, damaged relationships, and increased turnover all signal mismanaged or excessive conflict (Jehn, 1995; Nicotera & Jameson, 2021). In extreme cases, personal attacks and bullying may occur, especially when relational conflict escalates unchecked (Dahle, 2001). Yet when carefully moderated, conflict can produce highly positive results. Constructive conflict—especially moderate levels of task conflict—encourages idea generation, critical thinking, and more robust decision-making (De Dreu & Weingart, 2003). It clarifies goals, improves group processes, and, once resolved, can foster stronger interpersonal bonds and team cohesion. Organizations such as Intel have recognized these opportunities, implementing “constructive confrontation” programs to teach employees how to engage in conflict respectfully and productively, focusing on issues rather than personalities (Dahle, 2001). Longitudinal studies suggest that the timing of conflict also matters—effective teams often display rising levels of process conflict toward the end of projects and moderate task conflict midstream, while maintaining low levels of relationship conflict throughout (Jehn & Mannix, 2001). Ultimately, conflict is not inherently harmful; it is the way it is understood, framed, and resolved that determines whether it becomes a force for disruption—or a catalyst for innovation and growth.

6 Causes of Conflict

1. Organizational Structure

Organizational structure plays a pivotal role in shaping how conflict manifests within a workplace. Different structural designs—such as hierarchical, flat, or matrix—create distinct pathways for communication, authority, and decision-making, each with its own potential for tension. In particular, matrix structures are known to embed decisional conflict into the system itself. This occurs because employees, especially managers, are often required to report to multiple supervisors across functional and geographic lines, leading to ambiguity in priorities and accountability (Jaffe, 2000). A prime example is ABB Inc., a global company structured around both country and industry dimensions. With over 1,200 geographic units and 50 industry-based divisions, ABB’s matrix design has been cited as a source of confusion and conflict due to overlapping responsibilities and competing directives (Taylor, 1991). While such structures aim to enhance flexibility and responsiveness, they also increase the likelihood of authority disputes, goal misalignment, and interpersonal friction—especially when roles are not clearly defined or when cultural norms differ across units. Thus, organizational structure is not merely a backdrop for conflict; it actively shapes the conditions under which conflict arises and must be managed.

2. Limited Resources

Scarcity of resources is one of the most persistent and tangible causes of conflict in organizational settings. When critical assets such as time, funding, personnel, or equipment are limited, individuals and departments often find themselves competing to secure what they need to meet their goals. This competition can lead to tension, resentment, and breakdowns in collaboration, especially when resource allocation is perceived as unfair or opaque (Jaffe, 2000). For example, if one team receives upgraded technology while another continues to struggle with outdated tools, feelings of inequity may arise, undermining morale and trust. Moreover, resource scarcity can exacerbate existing structural or interpersonal tensions, particularly when departments are interdependent. A sales team may push for expedited delivery to close deals, while the logistics team resists due to budget constraints—each acting rationally within their own priorities, yet clashing over limited means (Jehn & Mannix, 2001). In such cases, conflict is not merely a byproduct of scarcity but a signal that organizational systems may need recalibration to balance competing needs. Effective communication and transparent decision-making processes are essential to mitigate these tensions and transform resource-based conflict into opportunities for strategic alignment.

3. Task Interdependence

Task interdependence refers to the degree to which individuals or teams rely on one another to complete their work, and it is a common source of conflict in collaborative environments. When tasks are tightly linked—such as in sequential or reciprocal workflows—delays, miscommunication, or mismatched expectations in one area can ripple across the organization, creating frustration and blame (Jehn, 1995; Thompson, 1967). For example, a marketing team may depend on the creative department to deliver assets before launching a campaign. If the creative team misses a deadline, the marketing team’s goals are jeopardized, potentially leading to interpersonal tension or organizational bottlenecks. Research shows that higher levels of task interdependence increase the likelihood of both task and relationship conflict, especially when roles are unclear or when teams lack shared norms for collaboration (Lee et al., 2015; Jehn & Mannix, 2001). However, task interdependence can also foster cooperation and improve performance when managed effectively—particularly when teams have strong trust, open communication, and aligned incentives (Wageman, 1995; Bradley et al., 2012). Thus, while interdependence is essential for complex projects, it must be supported by clear processes and relational safeguards to prevent conflict from undermining team cohesion.

4. Incompatible Goals

Incompatible goals are a frequent and often unavoidable source of conflict in organizations, particularly when different departments or individuals pursue objectives that are misaligned or mutually exclusive. This type of conflict arises when one party’s success is perceived to hinder another’s, creating tension and competition rather than collaboration (Jaffe, 2000). For example, a sales manager may be incentivized to offer expedited shipping to close deals quickly, while a logistics manager may be rewarded for minimizing transportation costs. These conflicting priorities can lead to disputes over resource allocation, decision-making authority, and performance metrics. Such goal misalignment is often embedded in compensation structures or departmental mandates, which unintentionally pit teams against one another (Wilmot & Hocker, 2010). Resolving these conflicts requires systemic adjustments—such as aligning incentives with shared organizational outcomes or redesigning workflows to support interdepartmental cooperation. Without such interventions, incompatible goals can erode trust, reduce efficiency, and foster siloed thinking. As organizations grow more complex, the need to reconcile competing objectives becomes critical to maintaining cohesion and strategic focus.

5. Personality Differences

Personality differences are a natural and inevitable aspect of workplace dynamics, yet they often serve as a catalyst for conflict when not properly understood or managed. Individuals bring distinct temperaments, values, emotional responses, and communication styles to their roles, which can lead to misunderstandings, tension, or even interpersonal clashes (Wilmot & Hocker, 2010). For instance, employees high in neuroticism may perceive interactions as more emotionally charged, while those high in agreeableness may avoid confrontation altogether—both responses can distort team dynamics and hinder resolution efforts (Brebner, 2001; Sandy, Boardman, & Deutsch, 2014). Research also shows that personality traits influence preferred conflict resolution styles. The Thomas-Kilmann model identifies five approaches—competing, collaborating, compromising, avoiding, and accommodating—and individuals tend to gravitate toward styles that align with their personality profiles (Messarra, Karkoulian, & El-Kassar, 2016). For example, extroverts may favor direct engagement, while introverts might prefer reflective or indirect methods. These differences can be exacerbated by generational or cultural factors, which shape expectations around assertiveness, feedback, and emotional expression. When personality-driven conflict is left unaddressed, it can escalate into relational discord, reduce psychological safety, and impair team performance. However, organizations that foster emotional intelligence, empathy, and inclusive communication can transform personality diversity into a source of strength rather than division.

6. Miscommunication and Information Gaps

Miscommunication and information gaps are among the most pervasive—and often preventable—sources of conflict in organizations. Whether caused by unclear expectations, ambiguous language, cultural misunderstandings, or digital overload, poor communication disrupts workflow, breeds mistrust, and distorts intentions (Oetzel, Ting-Toomey, Masumoto, & Yokochi, 2003). A message delivered hastily in a team chat, or an email lacking tone and context, can be interpreted in ways far removed from its intent, particularly in remote or cross-cultural environments. Additionally, delayed access to critical information or inconsistent updates across departments may lead to frustration and finger-pointing, undermining collaboration (Nicotera & Jameson, 2021). These breakdowns are often worsened by differing communication styles—some team members prefer direct and concise messaging, while others value relational context and indirect cues (Ting-Toomey, 1999). Without intentional design and proactive norms for transparency and feedback, miscommunication and information gaps can escalate into interpersonal or intergroup conflict. On the other hand, teams that cultivate active listening, face-saving strategies, and rhetorical mindfulness—such as clarifying intent, checking for understanding, and contextualizing tone—are better equipped to turn potential confusion into constructive dialogue and alignment.

Outcomes of Conflict

Conflict isn’t inherently destructive; its outcomes are shaped by how it’s managed. At one end of the spectrum, poorly handled conflict leads to burnout, turnover, absenteeism, and productivity loss—especially when it festers or escalates without resolution (De Dreu & Weingart, 2003). Interpersonal tension may poison team dynamics, distort goals, and provoke power struggles that stall innovation. Meanwhile, unresolved conflict consumes managerial energy and diverts focus from strategic priorities (Rahim, 2011).

But conflict, when approached constructively, can sharpen perspectives, deepen understanding, and catalyze change. Teams that engage in task-focused conflict—debating ideas rather than personalities—often emerge more aligned, creative, and adaptable (Jehn & Mannix, 2001). Constructive conflict prompts reevaluation of assumptions, encourages participatory decision-making, and surfaces hidden risks or opportunities. It can also strengthen trust, particularly when disagreements are aired openly and resolved respectfully.

Importantly, whether conflict becomes a liability or a leadership lever depends on context: power dynamics, organizational norms, and conflict competence all influence whether outcomes trend toward dysfunction or growth. Leaders who foster psychological safety and conflict literacy create cultures where differences become fuel rather than friction.

Workplace Strategy Pack

Empowering Employees Amid Unequal Safety Measures

When employees discover that supervisors secretly lock their offices to protect themselves from potential violence—while leaving frontline staff exposed in unsecured spaces—it can erode trust, heighten fear, and signal a breakdown in organizational transparency. This Strategy Pack offers tools to help employees advocate for equitable safety, foster open communication, and navigate the emotional toll of feeling unprotected.

Understanding the Impact

Psychological Safety & Trust

Psychological safety—the belief that one can speak up or take risks without fear—is foundational to employee well-being (Edmondson, 1999). When safety measures are unevenly distributed, employees may feel expendable or devalued, leading to:

- Increased anxiety and hypervigilance

- Reduced engagement and morale

- Distrust in leadership and organizational culture (Kahn, 1990)

Organizational Silence

Fearful employees may avoid voicing concerns, contributing to a culture of silence (Morrison & Milliken, 2000). This silence can perpetuate unsafe conditions and prevent necessary reforms.

Strategic Actions for Employees

1. Initiate Constructive Dialogue

Use assertive, non-confrontational language to raise concerns. Frame safety as a shared organizational priority.

Example: “I’ve noticed that some areas are more secure than others. Could we explore ways to ensure consistent safety measures across all workspaces?”

2. Leverage Formal Channels

Submit concerns through HR, safety committees, or anonymous reporting systems. Document incidents or patterns that raise alarm.

Tip: Reference OSHA guidelines or internal safety policies to strengthen your case.

3. Build Collective Voice

Form alliances with colleagues to present unified feedback. Collective advocacy often carries more weight and reduces individual risk (Detert & Edmondson, 2011).

4. Request Transparency

Ask leadership to clarify safety protocols and emergency procedures. Transparency builds trust and reduces speculation.

Suggested question: “Can you share the rationale behind current security measures and how they’re being evaluated for fairness?”

5. Practice Situational Awareness

Stay informed about exits, emergency contacts, and response protocols. Encourage regular safety drills and training.

6. Protect Your Emotional Health

Fear of violence can take a psychological toll. Seek support through employee assistance programs (EAPs), peer networks, or mental health professionals.

Communication Tips for High-Stakes Conversations

- Use “I” statements: “I feel unsafe when…” rather than “You don’t care…”

- Stay solution-focused: Offer ideas, not just complaints

- Avoid escalation: Keep tone calm and professional, even when emotions run high

- Follow up: Document conversations and revisit unresolved issues respectfully

Long-Term Culture Change

Employees play a vital role in shaping organizational culture. By advocating for equitable safety and transparent communication, you help build a workplace where everyone feels valued and protected.

References

Detert, J. R., & Edmondson, A. C. (2011). Implicit voice theories: Taken-for-granted rules of self-censorship at work. Academy of Management Journal, 54(3), 461–488. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2011.61967925

Edmondson, A. (1999). Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44(2), 350–383. https://doi.org/10.2307/2666999

Kahn, W. A. (1990). Psychological conditions of personal engagement and disengagement at work. Academy of Management Journal, 33(4), 692–724. https://doi.org/10.5465/256287

Morrison, E. W., & Milliken, F. J. (2000). Organizational silence: A barrier to change and development in a pluralistic world. Academy of Management Review, 25(4), 706–725. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2000.3707697

Occupational Safety and Health Administration. (n.d.). Workplace violence. https://www.osha.gov/workplace-violence

Conflict in organizations is inevitable, but not insurmountable. When leaders and teams understand its roots—like miscommunication and information gaps—and recognize the varied outcomes it can produce, they are better equipped to respond thoughtfully and strategically. Constructive conflict doesn’t just reveal problems—it opens doors to innovation, alignment, and trust. By fostering cultures of transparency, psychological safety, and rhetorical mindfulness, organizations can turn friction into forward momentum. In the end, the measure of success isn’t the absence of conflict, but the presence of resilience and dialogue.

Discussion Questions

- What are some key contributors to workplace conflict, and how might organizational culture or communication style influence them?

- How can workplace conflict impact individuals and teams—both positively and negatively? Which professions face a higher risk of workplace violence, and what underlying factors contribute to that vulnerability?

- Reflecting on your own experiences, what short-term and long-term effects have you observed from conflict at work? Were there any unexpected outcomes?

Section 10.4: Conflict Management

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, you should be able to do the following:

- Describe the five conflict-handling styles—avoiding, accommodating, compromising, competing, and collaborating—using real-world examples and current research.

- Evaluate the strengths and limitations of each style based on situational factors such as power dynamics, emotional investment, and organizational context.

- Identify their own dominant conflict-handling style and reflect on its effectiveness in various personal and professional settings.

- Analyze the role of psychological safety and emotional intelligence in promoting constructive conflict and encouraging diverse perspectives.

- Explain the risks of having too little conflict and articulate strategies for fostering healthy disagreement in team environments.

- Apply adaptive conflict management techniques to match style to context and support long-term relationship-building and innovation.

- Engage in respectful, issue-focused dialogue by challenging ideas without attacking individuals, using collaborative communication practices.

Conflict is an inevitable feature of organizational life, arising from diverse goals, values, roles, and communication patterns. Far from being purely disruptive, conflict—when managed constructively—can catalyze innovation, strengthen relationships, and enhance decision-making (De Dreu & Gelfand, 2008). Organizational communication scholars emphasize that the way conflict is framed, expressed, and resolved reflects deeper cultural, structural, and interpersonal dynamics (Putnam & Poole, 1987).

Modern organizations face increasingly complex environments, where collaboration across teams, cultures, and technologies demands nuanced conflict management strategies. Research shows that effective conflict management is not merely about resolution, but about fostering climates of openness, psychological safety, and ethical dialogue (Mikkelsen & Clegg, 2018). Communication is central to this process—both as a source of conflict and as a tool for transformation.

This chapter explores five foundational strategies for managing conflict—changing structure, altering team composition, creating shared opposition, applying majority rule, and collaborative problem-solving. These approaches are examined through the lens of organizational communication theory, with attention to their ethical implications, practical applications, and limitations. By integrating insights from emotional intelligence, facework, and communication climate, this chapter aims to equip readers with a holistic framework for navigating conflict in today’s dynamic workplaces.

There are a number of different ways of managing organizational conflict, which are highlighted in this section. Conflict management refers to resolving disagreements effectively.

3 Ways to Manage Conflict

1. Change the Structure

When organizational structure is the root of dysfunctional conflict, redesigning that structure can offer an effective resolution. Structural conflict often arises not from personal animosity but from misaligned roles, incompatible goals, and competing performance metrics (Galbraith, Downey, & Kates, 2002). Organizational communication scholars highlight that systemic tensions—rather than individual behaviors—are frequently the true drivers of conflict in the workplace (Putnam & Poole, 1987). Consider the case of Vanessa, a lead engineer in charge of product development, and Tom, a procurement officer. Vanessa submits a list of components for purchase, only to have Tom reject key items based on cost concerns. Frustrated, she challenges his refusal, arguing that delays jeopardize the entire project. Tom counters that Vanessa’s preferences for leading-edge components consistently strain his budget. This exchange reflects a deeper issue: their roles are governed by conflicting incentives. Sharon, the vice president of the business unit, recognizes the structural nature of their conflict and proposes a solution. She changes their evaluation criteria so both Vanessa and Tom are jointly responsible for total product cost and performance outcomes. This realignment shifts them from adversaries to collaborators. When departments themselves are in conflict, a structural remedy might involve having both report to a common executive who can coordinate their priorities. By adjusting organizational architecture, leaders can foster environments that encourage cooperation over competition and support aligned performance goals.

Strategy 1: Change the Composition of the Team

Addressing Dysfunction Through Design

When interpersonal conflict stems from incompatible personalities, values, or working styles, adjusting the composition of the team may be necessary. This strategy focuses on realigning team membership to foster more productive collaboration and reduce persistent tension.

Organizational communication research suggests that conflict is often amplified when individuals with opposing styles or goals are placed in close proximity without adequate support or mediation (Gordon et al., 1990). In such cases, separating antagonistic members or introducing new voices can shift the team’s dynamic toward cooperation.

For example, if two team members consistently clash over decision-making approaches—one favoring innovation and the other risk-aversion—leaders might reassign one member to a different project or bring in a third party to mediate and balance perspectives. In more extreme cases, replacing a team member may be warranted if the conflict undermines group cohesion and performance.

However, scholars caution that changing team composition should not be the first resort. Before making personnel changes, leaders might try assigning conflicting parties to a low-stakes collaborative task, allowing them to build trust and mutual understanding in a controlled setting (Open Text WSU, n.d.). Even subtle adjustments—like seating arrangements—can reduce tension; research shows that seating antagonists side-by-side rather than face-to-face can decrease conflict intensity (Gordon et al., 1990).

Ultimately, this strategy recognizes that team chemistry matters. By thoughtfully curating team membership, leaders can create environments where diverse perspectives enhance rather than hinder collaboration.

Strategy 2: Create a Common Opposing Force

Transforming Rivalry into Collaboration

Group conflict within organizations often stems from internal competition—whether over resources, recognition, or strategic priorities. One way to mitigate this tension is by redirecting attention toward a shared external challenge or goal. Rather than allowing internal rivalries to fester, leaders can foster unity by emphasizing what the team collectively stands to gain—or lose—together.

Consider the case of two software development groups competing for limited marketing funds. Each team wants to maximize exposure for its product, leading to friction and siloed efforts. However, when leadership shifts the focus to an external competitor threatening market share, the teams begin to collaborate. By pooling resources and aligning messaging, they enhance the company’s overall marketing effectiveness and strengthen its competitive position.

Importantly, the “shared goal” need not be a rival company. It could be a broader challenge—such as navigating an economic downturn, responding to industry disruption, or preserving jobs during a recession. In these cases, departments that previously clashed may find common purpose in safeguarding organizational stability.

Organizational communication scholars note that aligning teams around shared goals reduces tension caused by misaligned priorities and fosters a sense of collective identity (Kaplan, 2023; Edmondson & Lei, 2014). This approach taps into social identity theory, which suggests that people are more likely to cooperate when they perceive themselves as part of a unified group facing a common challenge.

Strategy 3: Using Participatory Decision-Making

Balancing Voice and Efficiency in Group Conflict

In some cases, group conflict can be resolved through a democratic process—specifically, by allowing members to vote on a proposed solution. When implemented thoughtfully, participatory decision-making can foster a sense of fairness and inclusion, especially when all voices are heard and the process is transparent. The idea with the most support is adopted, and the group moves forward with a shared understanding of the outcome.

However, organizational communication scholars caution that this strategy must be used judiciously. If majority rule becomes the default mechanism—particularly when the same individuals or subgroups consistently “win”—it can breed resentment and disengagement among minority voices (Kaner et al., 2014). Overreliance on voting can also shortcut meaningful dialogue, reducing complex issues to binary choices and undermining the collaborative spirit of conflict resolution.

To be effective, participatory decision-making should follow a healthy discussion of the issues at hand. This includes exploring divergent perspectives, acknowledging emotional undercurrents, and seeking common ground. When used sparingly and with care, voting can serve as a practical tool for closure—especially when consensus is elusive but respectful deliberation has occurred.

Ultimately, the goal is not just to make a decision, but to ensure that the process itself strengthens group cohesion and trust. Leaders and facilitators play a key role in framing the decision, guiding discussion, and ensuring that all members feel heard—even if their preferred outcome isn’t selected.

Strategy 4: Engage in Collaboraitve Problem Solving

Focusing on Issues, Not Individuals

Collaborative problem-solving is one of the most widely endorsed approaches to conflict resolution in organizational settings. Rather than assigning blame or defending positions, this strategy encourages individuals or groups to focus on the problem itself—its causes, implications, and potential solutions. The goal is to shift attention away from interpersonal tension and toward shared understanding and constructive action.

Organizational communication scholars emphasize that effective problem-solving requires participants to uncover the root cause of the conflict, not just its surface symptoms (Bernstein & Ablon, 2011). This approach recognizes that in most conflicts, neither side is entirely right or wrong. Instead, each party brings valid concerns, perspectives, and constraints that must be acknowledged and integrated into the solution.

Collaborative problem-solving also promotes psychological safety, allowing individuals to express concerns without fear of retaliation or dismissal (Edmondson & Lei, 2014). When facilitated well, it fosters creativity, mutual respect, and long-term resolution—rather than temporary compromise or avoidance. Leaders play a critical role in guiding this process by modeling empathy, encouraging open dialogue, and helping teams move from reactive stances to proactive collaboration.

2. Managing Communication Climate

Creating Conditions for Resolution

A positive communication climate is essential for constructive conflict management in organizations. Defined as the emotional tone or atmosphere of interactions, communication climate shapes how individuals perceive messages, interpret intent, and respond to disagreement (Wood, 1999). In supportive climates, employees feel respected, heard, and valued—conditions that foster openness, trust, and collaboration. Conversely, defensive climates—marked by judgment, control, and indifference—can escalate conflict and inhibit resolution. Research shows that relational messages often carry subtext beyond content, signaling inclusion, dominance, or disregard through tone, body language, and even silence (Jahangir, Safdar, & Zaheen, 2021). When individuals perceive that their social and relational needs—such as respect, belonging, and autonomy—are unmet, they are more likely to react with defensiveness or disengagement. Leaders play a pivotal role in shaping climate by modeling empathy, encouraging dialogue, and removing barriers to honest communication. By cultivating a climate where people feel psychologically safe and relationally affirmed, organizations can reduce the frequency and intensity of conflict and promote ethical, solution-focused engagement.

3. Facework and Emotional Intelligence

Managing Identity and Emotion in Conflict

In addition to structural and strategic approaches to conflict management, the interpersonal dimension plays a critical role in shaping how conflict unfolds and whether it is resolved constructively. Two key concepts—facework and emotional intelligence—help explain why some conflicts escalate while others invite cooperation. Facework refers to the communicative behaviors individuals use to preserve self-image and protect others’ identities during interaction (Goffman, 1967; Cupach & Metts, 1994). In conflict situations, threats to “face”—such as public criticism, condescension, or exclusion—can trigger defensiveness and resistance, making resolution more difficult. Leaders and team members who practice face-sensitive communication are more likely to maintain respect, foster psychological safety, and avoid identity-based escalation.

Equally important is emotional intelligence, which involves the ability to recognize, understand, and manage one’s own emotions and empathize with the emotions of others (Goleman, 1995). High emotional intelligence supports key conflict management behaviors such as self-regulation, perspective-taking, and relational repair. Individuals with strong EI are better equipped to remain calm under pressure, listen without judgment, and respond with empathy—even when disagreement arises. Research shows that emotional intelligence enhances trust, collaboration, and long-term problem-solving (Edmondson & Lei, 2014; Kellot, 2024). Together, facework and emotional intelligence provide a human-centered foundation for conflict resolution, helping organizations foster cultures of dignity, dialogue, and interpersonal insight.

5 Conflict-Handling Styles

Adapting Approaches to Fit the Situation

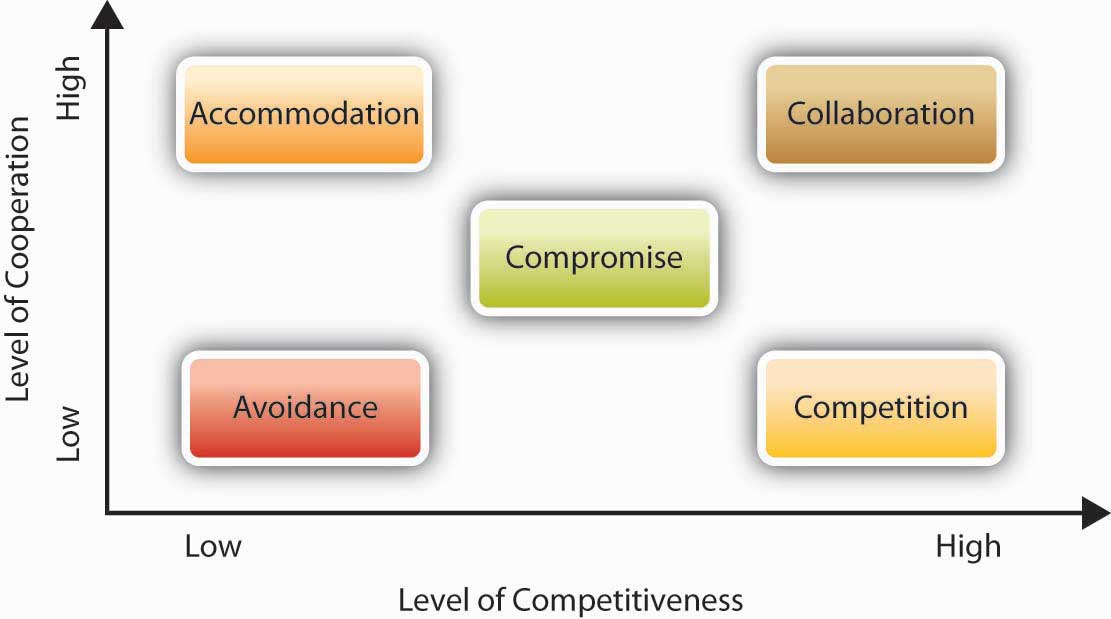

Conflict is not one-size-fits-all. While structural and interpersonal strategies can shape the conditions for resolution, the way individuals respond to conflict in the moment—their conflict handling style—often determines whether tensions escalate or transform into collaboration. Organizational communication scholars Kenneth Thomas and Ralph Kilmann developed a widely used framework that identifies five distinct styles of conflict management: avoiding, accommodating, competing, compromising, and collaborating. These styles are based on two dimensions: assertiveness (the degree to which one pursues their own concerns) and cooperativeness (the degree to which one seeks to satisfy others’ concerns) (Thomas & Kilmann, 1974).

Each style has its strengths and limitations, and no single approach is universally effective. Instead, effective conflict managers demonstrate style flexibility—the ability to assess the context, stakes, and relationships involved, and choose the most appropriate response. For example, avoidance may be useful when emotions are high and a cooling-off period is needed, while collaboration is ideal when long-term relationships and creative solutions are at stake. Cultural norms, emotional intelligence, and communication climate also influence which styles are preferred and how they are perceived (Rahim, 2011; Coursera, 2025).

This section explores each of the five conflict handling styles, offering insights into when and how they can be used effectively in organizational life. By understanding these styles, individuals and teams can better navigate disagreements, preserve relationships, and foster ethical, productive dialogue.

1. Avoidance

The avoiding conflict style is characterized by low assertiveness and low cooperativeness. Individuals who adopt this approach tend to withdraw from conflict rather than engage with it directly, often denying that a problem exists or postponing decisions that might provoke disagreement. This style may be driven by discomfort with confrontation, fear of escalation, or personality traits such as a high need for affiliation or harmony. Common expressions include statements like “I don’t think there’s a problem” or “Let’s just move on,” signaling a reluctance to address underlying tensions. While avoidance can be appropriate in situations where the issue is minor, emotions are running high, or timing is poor, it becomes problematic when important concerns are consistently sidestepped. Overuse of this style can lead to unresolved issues, strained relationships, and diminished trust, especially if others perceive the avoider as indifferent or passive-aggressive. Organizational communication research suggests that avoidance may offer short-term relief but often allows conflict to simmer beneath the surface, potentially leading to greater dysfunction over time (Thomas & Kilmann, 1974; Shonk, 2025; Pollack, 2021). Developing emotional intelligence and psychological safety can help individuals move beyond avoidance and engage in more constructive dialogue.

2. Accommodation

The accommodating conflict style is marked by a high level of cooperativeness and low assertiveness. Individuals who use this approach tend to prioritize maintaining harmony and preserving relationships over asserting their own needs. They might say things like, “Let’s do it your way,” or “If it’s important to you, I can go along with it,” reflecting a willingness to concede for the sake of peace (Bennett, 2022).

This style can be effective when the issue at stake is far more important to the other party than to the accommodator, or when showing deference might help build goodwill and trust (AllWin Conflict Resolution Training, 2025). However, habitual accommodation can lead to overlooked personal needs, growing resentment, and the erosion of self-confidence. Over time, consistent self-suppression may create imbalances in the relationship dynamic and leave individuals feeling undervalued (Thomas & Kilmann, 1974).

Organizational communication experts recommend that accommodation be used strategically and sparingly. Balancing empathy with assertiveness through techniques such as boundary-setting and self-reflection can help ensure that accommodation remains a conscious act of compassion rather than a default behavior (Bennett, 2022; AllWin Conflict Resolution Training, 2025).

3. Compromise

The compromising conflict style represents a balanced approach, combining moderate assertiveness with moderate cooperativeness. Individuals who use this style aim to find a mutually acceptable solution by making concessions, often saying things like, “Perhaps I ought to reconsider my initial position,” or “Maybe we can both agree to give in a little” (MT Copeland, 2021). This style is particularly useful when both parties have equal power and the issue is moderately important, allowing for a resolution that partially satisfies everyone involved (CMA Consulting, 2025).

In a compromise, each party gives up something of value to reach a middle ground. A well-known example occurred in 2005 when the Lanesborough Hotel in London mistakenly advertised rooms for £35 instead of £350. Faced with a flood of bookings and a potential public relations crisis, the hotel agreed to honor the rate for up to three nights per guest—demonstrating a strategic compromise that preserved both customer goodwill and financial stability (Horowitz et al., 2006).

While compromise can lead to quick and fair outcomes, it may also result in surface-level solutions that fail to address deeper issues. Overuse of this style can leave parties feeling unsatisfied or resentful if they believe they’ve conceded too much (Niagara Institute, 2021). Experts recommend treating compromise as a temporary fix when time is limited or when maintaining relationships is a priority, but not as a substitute for deeper collaboration (Thomas & Kilmann, 1974; Shonk, 2025).

4. Competition

The competing conflict style is defined by high assertiveness and low cooperativeness. Individuals who adopt this approach prioritize their own goals and outcomes, often pushing for their preferred solution regardless of others’ perspectives or emotional responses. This style is typically characterized by direct, forceful communication and a win-lose mindset, where success is measured by achieving one’s own objectives (Thomas & Kilmann, 1974; Bennett, 2021). People using this style may say things like, “This is the only way forward,” or “I’m not backing down,” reflecting a strong desire to control the outcome.

While competition can be effective in situations requiring quick, decisive action—such as emergencies, ethical dilemmas, or when defending against harmful alternatives—it carries significant relational risks. Overuse of this style may lead to damaged trust, reduced collaboration, and strained interpersonal dynamics (CMA Consulting, 2025; Shonk, 2025). For example, a manager who overrides team input to enforce a policy may achieve short-term clarity but risk long-term disengagement and resentment among staff (Niagara Institute, 2021).

Organizational communication experts caution that the competing style should be used sparingly and strategically. When employed with emotional intelligence and transparency, it can project confidence and protect vital interests. However, when used indiscriminately, it may stifle innovation, escalate conflict, and erode morale (Rahim, 2011; Sorensen, 1999). Leaders are encouraged to balance assertiveness with empathy and to consider alternative styles—such as collaboration or compromise—when relationship-building and shared ownership are critical.

5. Collaboration

The collaborating conflict style is distinguished by high assertiveness and high cooperativeness. Individuals who adopt this approach aim to resolve conflict through open dialogue, mutual respect, and integrative problem solving. Rather than viewing conflict as a win-lose scenario, collaborators seek win-win outcomes by advocating for their own needs while actively listening to and incorporating the concerns of others (Thomas & Kilmann, 1974; Pollack, 2025). This style encourages both parties to challenge ideas—not each other—and to work together toward solutions that satisfy everyone’s core interests.

Collaboration is especially effective when the issue is complex, emotionally charged, or when long-term relationships and sustainable outcomes are at stake (MT Copeland, 2021; CMA Consulting, 2025). For example, consider an employee who wishes to pursue an MBA and requests reduced work hours. Rather than taking rigid positions, both the employee and management can explore alternatives—such as online coursework or tuition support—that honor the employee’s career goals while meeting organizational needs. This integrative approach allows both parties to gain without sacrificing what is personally important.

While collaboration requires time, emotional investment, and skilled facilitation, it often leads to deeper trust, stronger team cohesion, and more innovative solutions (Pollack, 2025; OfficeRnD, 2024). Experts emphasize that collaboration is not merely compromise—it’s a creative process that uncovers shared values and builds lasting agreements.

Which Conflict Style Is Best?

In organizational behavior, there is no universally “correct” way to manage conflict. The most effective approach often depends on the context, the stakes involved, and the personalities of those involved (Shonk, 2025). While each of the five conflict styles—avoiding, accommodating, compromising, competing, and collaborating—has its place, the collaborating style is widely regarded as the most constructive in a broad range of situations. It fosters mutual understanding, encourages creative problem-solving, and strengthens relationships over time (Thomas & Kilmann, 1974; Pollack, 2025).

That said, most individuals tend to default to a dominant style. You might recognize this in a friend who always seeks confrontation or a colleague who consistently backs down. The key to successful conflict management lies in adaptability—the ability to match your style to the situation. For instance, avoiding conflict may be wise when the issue is trivial or emotionally charged, such as ignoring a reckless driver to avoid road rage. On the other hand, when a coworker repeatedly takes credit for your ideas, confrontation may be necessary to protect your professional integrity.

Research also reveals that hierarchical roles influence conflict style preferences. Managers are more likely to adopt a competing or forcing style, while subordinates tend to favor avoiding, accommodating, or compromising (Howat & London, 1980). Moreover, conflict styles can be contagious—individuals often mirror the approach of the person they’re engaging with. If one party is highly assertive or competitive, others may respond in kind, escalating the tension (Valamis, 2025).

Ultimately, the most effective conflict managers are those who can assess the situation, understand the dynamics at play, and strategically select the style that will lead to the best outcome for all parties involved.

What If You Don’t Have Enough Conflict Over Ideas?

Effective conflict management isn’t just about resolving disputes—it’s also about knowing when to encourage healthy disagreement. Many people assume that conflict is inherently negative, a sign that a team or meeting is dysfunctional. But the absence of conflict can be just as problematic. When no one challenges ideas or raises concerns, it may indicate that individuals are withholding their opinions, either out of fear, apathy, or a desire to avoid tension. This silence can lead to suboptimal decisions and missed opportunities for innovation.

In productive group discussions, diverse perspectives are not only expected—they’re essential. When people feel safe to voice dissent, they help identify flaws, refine proposals, and co-create stronger solutions. The key is to keep the conversation focused on the issue, not on personalities. For instance, saying “Jack’s ideas have never worked before” is dismissive and personal. A more constructive approach would be, “This production step uses a degreaser that’s considered hazardous. Can we explore a nontoxic alternative?” This reframes the concern as a shared problem-solving opportunity.

A modern example of the risks of too little conflict can be seen in the early culture of Airbnb. In its rapid growth phase, the company was praised for its collaborative and inclusive environment. However, internal reports later revealed that some teams were reluctant to challenge leadership decisions, especially around controversial topics like guest safety and regulatory compliance. This lack of pushback contributed to delayed responses to serious incidents, prompting public scrutiny and internal restructuring. Airbnb has since made efforts to foster constructive dissent, encouraging employees to speak up and debate ideas openly.

Ultimately, conflict isn’t the enemy—silence is. Organizations thrive when they create psychological safety, normalize disagreement, and train teams to engage in respectful, idea-focused dialogue. As Amy Gallo (2024) notes, “The healthiest teams aren’t the ones that avoid conflict—they’re the ones that know how to use it.”

Harnessing Conflict for Growth

Conflict is not a barrier to success—it’s a catalyst for progress when managed wisely. Each conflict style—avoidance, accommodation, compromise, competition, and collaboration—offers distinct advantages and limitations. The key is not to eliminate conflict, but to understand its dynamics and navigate it with intention. When individuals and organizations embrace open dialogue, match their approach to the situation, and foster psychological safety, they create space for innovation, accountability, and authentic relationships.

Whether you’re confronting a recurring workplace issue or encouraging diverse perspectives in a team setting, effective conflict management transforms disagreement into discovery. And in an era where inclusion, agility, and adaptability are more important than ever, mastering this skill is not just beneficial—it’s essential.

Workplace Strategy Pack

Drawing the Line Between Healthy Conflict and Aggression

Objective: To equip employees with the tools and awareness needed to recognize when workplace conflict shifts from constructive engagement to harmful aggression—and to respond effectively and professionally.

Why It Matters

Conflict is a natural and often necessary part of organizational life. When managed well, it can spark innovation, clarify misunderstandings, and strengthen relationships (Jehn, 1995). However, when conflict escalates into aggression—verbal hostility, intimidation, or personal attacks—it undermines psychological safety, damages trust, and can lead to burnout or turnover (Sutton, 2007).

Understanding the boundary between healthy conflict and aggression empowers employees to:

- Protect their emotional and psychological well-being

- Maintain professional relationships

- Foster a respectful and inclusive workplace culture

- Know when and how to seek support or intervention

Strategy Toolkit

1. Know the Signs of Healthy Conflict

Healthy conflict is issue-focused, respectful, and solution-oriented. It often includes:

- Open disagreement about ideas or processes

- Active listening and turn-taking

- Willingness to compromise or collaborate

- Focus on shared goals, not personal attacks

✅ Example: “I see your point, but I think we should consider another approach based on the data.”

2. Recognize Aggression

Aggression is behavior intended to dominate, intimidate, or harm. It may include:

- Raised voices, sarcasm, or insults

- Dismissive body language or tone

- Personal criticism unrelated to work

- Repeated interruptions or refusal to listen

❌ Example: “You clearly don’t know what you’re doing. This is a waste of time.”

3. Use the Conflict Continuum

Create a mental scale from 1 (constructive disagreement) to 10 (hostile aggression). Rate interactions to assess whether intervention is needed.

Tip: If a conversation feels like a 7 or higher, document it and consider involving a supervisor or HR.

4. Apply Assertive Communication

Assertiveness allows you to stand up for yourself without escalating the conflict.

- Use “I” statements: “I feel uncomfortable when…”

- Set boundaries: “Let’s keep this focused on the issue.”

- Redirect aggression: “I’d like to continue this when we’re both calm.”

5. Seek Mediation or Support

If aggression persists, request a neutral third party to facilitate resolution. Many organizations offer conflict resolution resources or employee assistance programs (EAPs).

Empowerment Tip

You have the right to a workplace where ideas are challenged—but people are respected. Trust your instincts. If a conversation feels unsafe, it probably is. Speaking up early can prevent escalation and protect your team’s culture.

References

Jehn, K. A. (1995). A multimethod examination of the benefits and detriments of intragroup conflict. Administrative Science Quarterly, 40(2), 256–282. https://doi.org/10.2307/2393638

Sutton, R. I. (2007). The no asshole rule: Building a civilized workplace and surviving one that isn’t. Business Plus.

Goleman, D. (2006). Social intelligence: The new science of human relationships. Bantam Books.

Tepper, B. J. (2000). Consequences of abusive supervision. Academy of Management Journal, 43(2), 178–190. https://doi.org/10.5465/1556375

Waldron, V. R., & Kelley, D. L. (2008). Communicating emotion: Theory, research, and context. In L. L. Putnam & D. K. Mumby (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of organizational communication (pp. 425–448). SAGE Publications.

Discussion Questions

- Identify three strategies for de-escalating a conflict situation—such as avoidance, accommodation, or compromise. What are the potential benefits of each approach? In what types of situations might each strategy be most useful or least effective? How could overreliance on one strategy impact relationships or outcomes?

- Do you approach conflict differently in professional settings than you do with friends or family? What factors influence your approach—such as hierarchy, emotional investment, or risk of repercussions? How does psychological safety (or lack thereof) affect your willingness to engage?

- What conflict-handling style do you tend to use at work—avoiding, accommodating, compromising, competing, or collaborating? How has this style helped or hindered you in specific situations? Can you recall a time when adapting your style might have led to a better outcome?

- Describe a situation where too little conflict led to a suboptimal decision or missed opportunity. What were the warning signs that conflict was being suppressed? How could healthy disagreement have improved the result? What role does psychological safety play in encouraging open dialogue?

Section 10.5: The Power of Negotiation in Organizational Life

Learning Objectives

After reading the following chapter, you should be able to do the following:

- Identify and describe the core stages of negotiation—from preparation to resolution—and recognize how each phase contributes to successful outcomes.

- Examine a variety of negotiation techniques including direct, integrative, and distributive approaches, and determine their application based on context, goals, and stakeholder dynamics.

- Recognize frequent missteps such as poor communication, unchecked assumptions, or escalation tendencies, and explore strategies to avoid or address these challenges.

- nvestigate the role of third-party negotiation formats—such as mediation, arbitration, and hybrid systems—and assess their benefits, limitations, and ethical considerations in organizational contexts.

- Learn strategic and emotional tools for navigating high-conflict, high-stakes scenarios, including emotional regulation, procedural neutrality, and culturally responsive communication methods.

- Reflect on how cultural norms, power imbalances, and organizational structures shape negotiation experiences and outcomes, and how to adapt strategies accordingly.

In every organization, negotiation is more than a transactional exchange—it’s a vital communication skill that shapes relationships, resolves disputes, and drives strategic progress. Whether you’re advocating for a budget increase, navigating team conflict, or striking a deal with a client, your ability to negotiate can determine success or setback.

This section explores negotiation as both art and process. It begins by breaking down the five phases of negotiation—from investigation and preparation to closure—and introduces strategic models that influence outcomes. You’ll examine the differences between distributive and integrative approaches, uncover behavioral and cognitive traps that derail negotiations, and discover how emotion, ego, and expectation shape results.

In today’s complex organizations, negotiation doesn’t always happen between two people at a table—it may involve cross-cultural teams, competing power dynamics, or external facilitators. That’s why we also delve into third-party negotiation, including mediation and arbitration, and examine the communication challenges unique to crisis situations and diverse cultural contexts.

Through this section, you’ll learn not just how to negotiate, but how to negotiate ethically, adaptively, and effectively—equipping yourself to lead with confidence and collaborate with clarity.

5 Phases of Negotiation

Phase One: Preparation

Effective negotiation in organizational contexts unfolds through a series of interdependent phases, each requiring distinct communicative competencies and strategic awareness. The process begins with Preparation, a foundational step that precedes formal investigation. In this phase, negotiators clarify their objectives, assess stakeholder interests, and identify potential constraints. Preparation also involves developing a strategic framework, including the identification of one’s Best Alternative to a Negotiated Agreement (BATNA)—a critical benchmark that informs decision-making and strengthens bargaining power (Fisher, Ury, & Patton, 2011; Malhotra & Bazerman, 2007). A strong BATNA enables negotiators to evaluate offers against viable alternatives, reducing susceptibility to pressure and enhancing confidence at the table (Cote, 2023).

Phase Two: Investigation

Following preparation, the Investigation phase centers on information gathering. Negotiators examine the context, history, and relational dynamics surrounding the issue, often conducting internal audits and stakeholder analyses to uncover underlying interests and priorities (Thompson, 2012). This phase is not limited to external research—it also requires introspective clarity about one’s own values, limits, and desired outcomes (Steinberg, as cited in Webber, 1998). Organizational communication scholars emphasize that this stage is often overlooked, yet it is essential for framing the negotiation as a collaborative problem-solving opportunity rather than a zero-sum contest (Gelfand et al., 2001).

Phase Three: Information Exchange

The third phase, Information Exchange, replaces the traditional “Presentation” label to better reflect the dialogic nature of modern negotiation. Here, parties share positions, clarify expectations, and begin to build rapport. This phase is shaped by both formal offers and informal communication, including verbal cues, tone, and nonverbal behaviors (Ma, 2007). Effective negotiators use this stage to uncover shared interests, establish trust, and assess the other party’s constraints and motivations. According to organizational behavior research, open and transparent exchange fosters integrative outcomes and reduces misinterpretation (Shell, 2006; Wheeler, 2023).

Phase Four: Bargaining and Problem Solving