Chapter 11: Decision Making in Organizations

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, you should be able to do the following:

- Describe the key components and processes involved in decision making.

- Differentiate between various decision-making models by comparing their strengths and limitations.

- Analyze the differences between individual and group decision-making approaches.

- Identify common decision-making traps and propose strategies to avoid them.

- Evaluate the advantages and disadvantages of different decision-making aids and tools.

- Apply ethical principles to real-world decision-making scenarios.

- Examine cross-cultural variations in decision-making practices and assess their implications in global contexts.

Section 11.1: Spotlight

Decision-Making Challenges During UMSL’s Campus Transformation

In 2024–2025, the University of Missouri–St. Louis launched the Transform UMSL initiative—a $110 million campus overhaul aimed at consolidating academic buildings, modernizing infrastructure, and enhancing student experience. While the long-term goals were ambitious, the implementation raised concerns among students, faculty, and staff. The demolition of the Social Sciences and Business Building (SSB), renovation of the Thomas Jefferson and Mercantile Libraries, and construction of the Richter Family Welcome Center disrupted daily campus life. Reports of inaccessible pathways, construction noise, power outages, and dust clouds during peak class hours suggest that decision-makers may have prioritized strategic vision over stakeholder experience (UMSL, 2025a; LJC, 2025).

UMSL leadership appeared to rely on a rational decision-making model, emphasizing long-term planning and cost-benefit analysis. This model is often praised for its structured approach but criticized for overlooking emotional and ethical dimensions (UMSL Comm 2231, 2025). The Transform initiative was guided by a Campus Master Plan approved in 2021, with input from external consultants and state officials. However, the lack of visible engagement with students and faculty during implementation suggests limited use of group decision-making models, which typically enhance buy-in and surface diverse perspectives.

Several decision-making traps may have influenced the rollout. Escalation of commitment—continuing with a plan despite mounting evidence of disruption—was evident as construction persisted during peak academic hours. Confirmation bias may have led leadership to focus on positive feedback from donors and legislators while ignoring campus-level concerns. Additionally, framing bias may have shaped communications that emphasized progress and transformation while downplaying the lived experience of those affected (Quizlet, 2025).

UMSL’s use of decision-making aids—such as strategic planning tools and architectural renderings—had mixed results. These aids helped visualize long-term goals and secure funding, but they may have obscured short-term consequences. The pros of these tools include clarity, structure, and alignment with institutional goals. The cons include rigidity, overreliance on expert input, and reduced responsiveness to real-time feedback (UMSL Comm 2231, 2025).

From an ethical decision-making standpoint, the initiative raises questions about transparency, inclusion, and respect for stakeholder wellbeing. Ethical frameworks such as universalism (process ethics) would suggest that the means of implementation matter as much as the outcomes. Blocking student access for photo opportunities during a Board of Curators visit, while symbolic, reinforced perceptions of exclusion and hierarchy. The absence of clear communication about environmental exposure during demolition further undermined trust (UMSL, 2025a).

In conclusion, the Transform UMSL initiative illustrates how strategic decision-making can falter when ethical considerations and stakeholder engagement are sidelined. A more inclusive approach—incorporating group decision-making, feedback loops, and ethical reflection—could have mitigated disruption and strengthened institutional credibility. This case underscores the importance of balancing vision with empathy in organizational decision-making.

References

LJC. (2025, May 2). UMSL’s campus transformation: A vision for the future. https://slccc.net/2025/05/02/umsls-campus-transformation-a-vision-for-the-future-ljc-project-update/

Quizlet. (2025). MGMT 335 Exam 3 Flashcards. https://quizlet.com/347551132/mgmt-335-exam-3-flash-cards/

UMSL. (2025a). Transform UMSL. https://www.umsl.edu/transform/index.html

UMSL Comm 2231. (2025). Chapter 11: Making decisions – Organizational behavior. https://umsystem.pressbooks.pub/organizationalbehavior/part/chapter-11-making-decisions/

Discussion Questions

- How might UMSL leadership have improved their decision-making process by incorporating more group decision-making models? Reflect on how diverse perspectives could have influenced the outcomes of the Transform UMSL initiative.

- What decision-making traps, such as escalation of commitment or confirmation bias, do you think were most evident in this case? How can organizations identify and avoid these traps during large-scale projects?

- The case highlights ethical concerns, including transparency and stakeholder inclusion. How should organizations balance long-term strategic goals with the immediate needs and wellbeing of their stakeholders? Reflect on how ethical frameworks could have guided UMSL’s leadership.

- UMSL relied heavily on decision-making aids like strategic planning tools and architectural renderings. What are the pros and cons of using such aids in organizational decision-making? Reflect on how these tools might have helped or hindered the initiative’s success.

Section 11.2: Understanding Organizational Decision Making

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, you should be able to do the following:

- Distinguish among key decision-making models—including rational, bounded rationality, intuitive, and creative approaches—and evaluate their applicability in varied professional contexts.

- Analyze the cognitive and environmental factors that influence the use of intuitive decision making in high-stakes or time-sensitive scenarios.

- Describe the stages of creative decision making, including problem identification, immersion, incubation, illumination, and verification/application, using real-world examples.

- Evaluate decision-making outcomes based on criteria such as effectiveness, creativity, feasibility, and the influence of expertise versus luck.

- Apply the fluency, flexibility, and originality framework to assess the creativity of a decision-making process in personal or organizational settings.

- Examine how personality traits (e.g., openness to experience) and situational factors (e.g., pressure, support systems) contribute to individual and team-level creativity in decision making.

- Demonstrate techniques to foster creativity, including brainstorming, wildstorming, and idea quotas, and assess their effectiveness in generating innovative solutions.

- Reflect on personal decision-making habits by identifying patterns of satisficing, intuition, and creativity—and strategize ways to enhance decision-making quality in future challenges.

Decision making is a foundational process in organizational life, shaping everything from strategic direction to daily operations. Whether choices are made by individuals, teams, or entire departments, the effectiveness of these decisions directly impacts organizational performance, adaptability, and culture (McKinsey, 2023; Hodgkinson & Starbuck, 2008).

Organizations face a spectrum of decision types—programmed and nonprogrammed, each falling into strategic, tactical, or operational categories (Lumen Learning, 2023). Programmed decisions are routine and often guided by established rules, while nonprogrammed decisions require deeper analysis and creativity due to their novelty and complexity (Simon, 1947; Drucker, 2010).

To navigate this complexity, scholars have proposed several models of decision making:

- The Rational Decision-Making Model assumes logical, step-by-step analysis to maximize outcomes, though it often fails to reflect real-world constraints (March, 2010).

- The Bounded Rationality Model, introduced by Herbert Simon, acknowledges cognitive limitations and the tendency to “satisfice” rather than optimize (Simon, 1955).

- The Intuitive Model emphasizes rapid, experience-based judgments, especially under time pressure or uncertainty (Sadler-Smith & Sparrow, 2008).

- The Creative Decision-Making Process highlights flexibility, fluency, and originality—qualities essential for innovation and problem solving (George, 2000).

In practice, organizations often blend these approaches, using tools like brainstorming, idea quotas, and wildstorming to stimulate divergent thinking and generate novel solutions (Gigerenzer et al., 1999). These techniques foster inclusive participation and help overcome cognitive biases that can derail sound judgment (Kahneman & Tversky, 1979).

Understanding these models and techniques equips organizational leaders and communicators to make more informed, ethical, and culturally sensitive decisions—especially in environments marked by complexity and change.

Decision Making

Decision making refers to selecting among alternative courses of action—including, at times, the choice to take no action at all. While some argue that management is essentially decision making, research suggests that nearly half of managerial decisions within organizations ultimately fail to achieve their intended outcomes (Ireland & Miller, 2004; Nutt, 2002; Nutt, 1999). Enhancing decision-making effectiveness is therefore a critical component of improving individual and organizational performance. This chapter explores how to make decisions independently and collaboratively, while identifying and avoiding common decision-making pitfalls.

Across all levels of an organization, individuals use the information available to them to make decisions that can shape careers, influence stakeholders, and alter the trajectory of entire enterprises. For instance, Boeing’s decision to fast-track the development of the 737 MAX—prioritizing speed over safety—resulted in two fatal crashes, regulatory scrutiny, and billions in financial losses. Conversely, when Microsoft pivoted toward cloud computing under Satya Nadella’s leadership, the company revitalized its business model and became one of the most valuable firms in the world.

Similarly, Netflix’s decision to reverse its 2011 pricing and service split after customer backlash demonstrated the importance of listening to stakeholders and adapting quickly. On the other hand, Blockbuster’s refusal to embrace streaming technology—despite the opportunity to acquire Netflix—led to its eventual collapse. These examples underscore a central truth: every decision carries consequences, and the ability to make informed, ethical, and adaptive choices is essential in today’s dynamic organizational landscape.

Types of Decisions

Many discussions of decision making mistakenly assume that only senior executives make decisions or that only their decisions carry weight. As Drucker (2010) cautioned, this is a dangerous oversimplification. In reality, decision making permeates every level of an organization, and each decision—regardless of scope—can influence outcomes, culture, and performance.Not all decisions are complex or carry significant consequences. Individuals make countless routine choices each day, such as what to wear, what to eat, or which route to take to work. These habitual decisions are known as programmed decisions—repetitive choices that rely on established rules or procedures (Lumen Learning, 2023). For instance, a retail store manager may automatically reorder inventory when stock levels fall below a predefined threshold. Similarly, customer service teams often follow a decision rule when handling complaints, such as offering a discount or free item to resolve recurring issues.In contrast, nonprogrammed decisions are unique, complex, and often made under conditions of uncertainty. They demand thoughtful analysis, creativity, and judgment (Simon, 1947). Consider Boeing’s response to safety concerns surrounding the 737 MAX aircraft. The company faced a nonprogrammed decision in determining how to address regulatory scrutiny, public trust, and engineering challenges. Conversely, when Microsoft pivoted toward cloud computing under Satya Nadella’s leadership, it revitalized its business model and became one of the most valuable firms in the world (McKinsey & Company, 2023).Crisis situations often trigger nonprogrammed decisions. During the COVID-19 pandemic, Airbnb made the difficult choice to restructure its workforce and pivot its business model toward long-term stays and virtual experiences. These decisions were made under pressure, with incomplete information, and had lasting implications for the company’s brand and operations. Such moments underscore the importance of gathering reliable data, engaging diverse perspectives, and communicating decisions transparently (Garvin, 2006).Organizational decisions can also be categorized by their level of impact:

- Strategic decisions define the long-term direction of the organization.

- Tactical decisions translate strategy into actionable plans.

- Operational decisions are day-to-day choices that keep the organization running (Simon, 1955).

To illustrate, imagine a coffee chain aiming to improve customer satisfaction. The CEO makes a strategic decision to prioritize customer experience. A regional manager develops a tactical plan to train baristas in personalized service. Finally, individual baristas make operational decisions each day—such as offering a complimentary drink to a dissatisfied customer—to fulfill that broader vision.Understanding the types and levels of decisions, and recognizing that decision making is distributed across the organization, empowers individuals to act with purpose, accountability, and alignment. It also reinforces the role of communication in shaping how decisions are made, shared, and implemented (Sadler-Smith & Sparrow, 2008).

Figure 11.4 Examples of Decisions Commonly Made Within Organizations

| Level of Decision | Examples of Decision | Who Typically Makes Decisions |

|---|---|---|

| Strategic Decisions | Should we merge with another company? Should we pursue a new product line? Should we downsize our organization? |

Top Management Teams, CEOs, and Boards of Directors |

| Tactical Decisions | What should we do to help facilitate employees from the two companies working together? How should we market the new product line? Who should be let go when we downsize? |

Managers |

| Operational Decisions | How often should I communicate with my new coworkers? What should I say to customers about our new product? How will I balance my new work demands? |

Employees throughout the organization |

In this chapter, we examine four prominent decision-making models that help explain and evaluate the effectiveness of nonprogrammed decisions: the rational decision-making model, the bounded rationality model, the intuitive decision-making model, and the creative decision-making model.

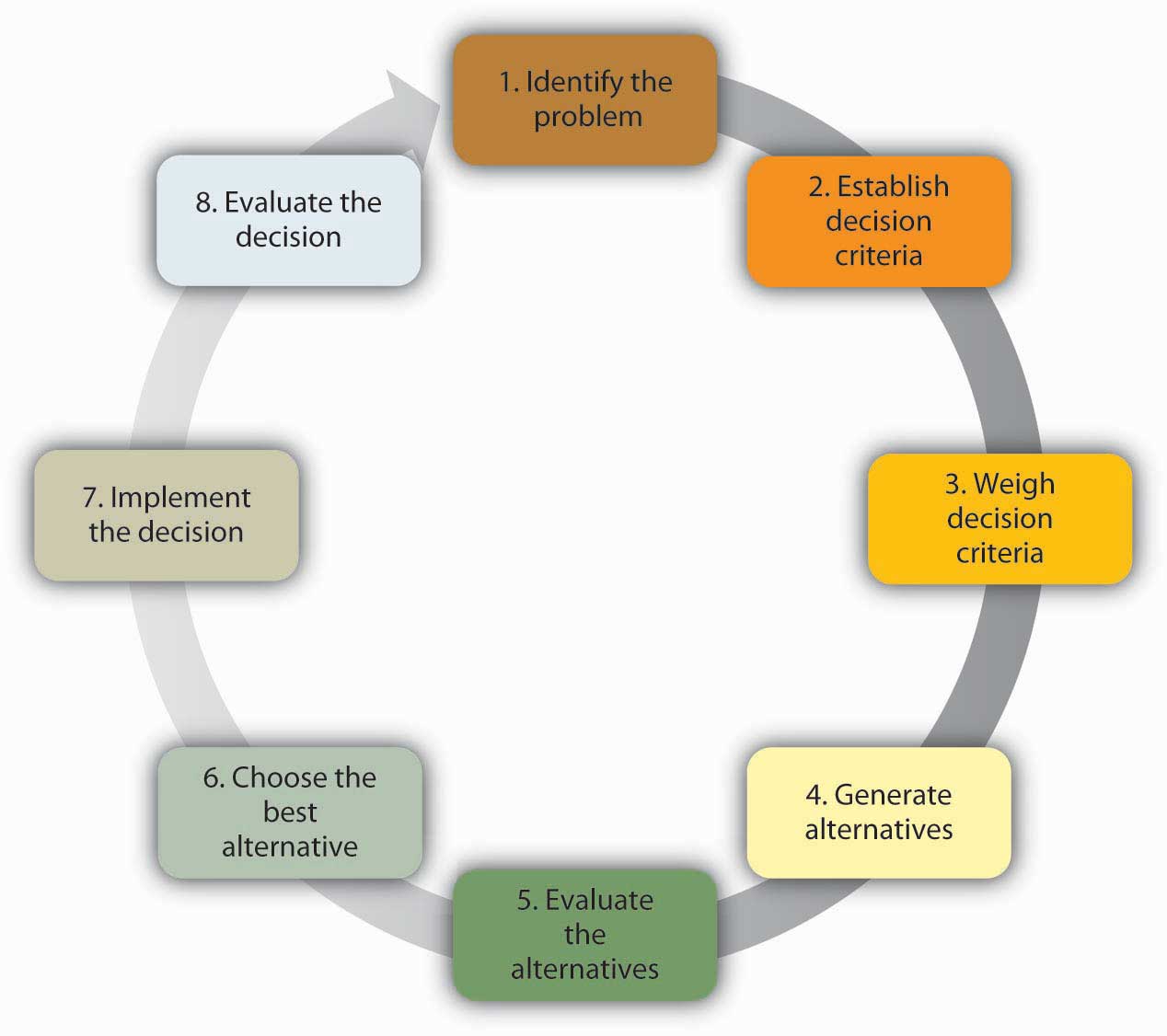

Making Rational Decisions: The Rational Decision-Making Model

The rational decision-making model outlines a structured, step-by-step approach aimed at maximizing outcomes. It assumes that decision makers have access to complete information, can objectively evaluate alternatives, and seek optimal solutions (Bazerman & Moore, 2013). For instance, consider someone purchasing their first electric vehicle. They begin by identifying the need for a new car (step 1), then determine key decision criteria such as passenger capacity, battery range, safety ratings, and price (step 2). Next, they weigh the importance of each factor—perhaps prioritizing range and safety over aesthetics (step 3). They then generate a list of alternatives (step 4), evaluate each option against the criteria (step 5), select the best fit (step 6), and make the purchase (step 7). Finally, they reflect on the outcome (step 8), which informs future decisions.

Despite its logical appeal, the rational model has limitations. It assumes that individuals are fully informed and free from biases—conditions rarely met in practice. Research by Nutt (1994) revealed that in 85% of organizational decisions, no alternative generation occurred, undermining the model’s effectiveness. Successful decision makers, however, tend to define objectives early, encourage broad participation, and avoid imposing their views (Nutt, 1998).

Moreover, the rational model can be derailed by emotional bias. For example, someone browsing electric vehicles online may become enamored with a sleek design and unconsciously adjust their criteria to justify the purchase, only to later realize the car lacks sufficient cargo space. Establishing criteria before exploring alternatives can help mitigate such bias. Additionally, generating a wide range of options increases the likelihood of finding a solution that balances competing priorities.

However, the model’s assumptions often clash with reality. Nobel laureate Herbert Simon argued that individuals operate under bounded rationality, meaning they make “satisficing” decisions—ones that are good enough—due to cognitive limitations and time constraints (Simon, 1955). For example, a manager selecting a software platform may not have the time or resources to evaluate every option, so they choose one that meets basic requirements and is familiar to the team.

In practice, decision makers rarely follow all eight steps of the rational model. Time pressure, information overload, and limited cognitive bandwidth often lead to shortcuts. The phenomenon of analysis paralysis, where excessive data collection impedes action, is common in tech firms. A Hewlett-Packard executive once admitted that prolonged analysis led to inaction: “We were gathering data instead of making decisions” (Zell, Glassman, & Duron, 2007).

Furthermore, not all decisions require optimal outcomes. When renting a short-term apartment, for example, individuals may settle for the first clean, affordable option near campus rather than exhaustively comparing every listing. In such cases, efficiency and practicality outweigh perfection.

Making “Good Enough” Decisions: The Bounded Rationalist Model

The bounded rationality model of decision making acknowledges that individuals operate under cognitive, informational, and time constraints that prevent them from making perfectly rational choices. Rather than evaluating every possible alternative, people often limit their search to a manageable set and select the first option that meets their minimum criteria—a process known as satisficing, a term coined by Nobel laureate Herbert Simon (Simon, 1955). This approach reflects a pragmatic balance between effort and outcome, especially in complex or time-sensitive situations.

For instance, recent college graduates frequently narrow their job search to a specific geographic region or industry, accepting the first offer that aligns with their basic needs—such as salary, location, and job title—rather than conducting a nationwide or global search for the optimal position (Profit.co, 2023). Similarly, consumers shopping for a laptop may choose a model that satisfies their core requirements (e.g., price, battery life, and screen size) without comparing every available brand and specification, especially when overwhelmed by choices or pressed for time (Boyce, 2023).

Bounded rationality is not a failure of logic but a reflection of how real-world decision making unfolds. It helps explain why executives under pressure may rely on heuristics or past experience rather than exhaustive analysis. For example, during a product launch, a marketing manager might choose a familiar advertising channel rather than exploring every possible media outlet, simply because it meets the campaign’s budget and timeline constraints. In such cases, satisficing allows for timely decisions that are “good enough,” even if they fall short of being optimal.

Understanding bounded rationality is essential for improving decision-making processes in organizations. By recognizing the limits of human cognition and the influence of context, leaders can design systems that support better choices—such as simplifying options, reducing information overload, and encouraging collaborative input (Gigerenzer et al., 1999).

Making Intuitive Decisions: Intuitive Decision-Making Model

The intuitive decision-making model offers an alternative to analytical approaches by emphasizing rapid, experience-based judgments made without conscious reasoning. Rather than systematically evaluating multiple options, intuitive decision makers rely on pattern recognition, emotional cues, and accumulated expertise to guide their choices (Klein, 2003). This model is particularly relevant in high-pressure environments where time constraints, uncertainty, and complexity make rational analysis impractical. In fact, a majority of managers report using intuition regularly—89% at least occasionally and 59% often—when making decisions (Burke & Miller, 1999).

Intuition plays a critical role in professions where decisions must be made quickly and with limited information. For example, emergency room nurses, airline pilots, and fire chiefs often rely on instinctive judgments honed through years of experience. Rather than weighing multiple alternatives, they scan the environment for familiar cues, mentally simulate outcomes, and adjust their actions accordingly (Salas & Klein, 2001). This process aligns with Klein’s (2003) Recognition-Primed Decision (RPD) model, which suggests that experts evaluate one option at a time, discarding or refining it based on anticipated results until a viable solution emerges.

Recent examples illustrate the power of intuitive decision making in dynamic settings. During the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic, public health officials had to make rapid decisions about lockdowns and resource allocation without complete data. Their choices were often guided by prior experience with outbreaks and instinctive assessments of risk. Similarly, tech leaders like Instagram’s Kevin Systrom used intuition to launch features like Stories, anticipating user behavior and market trends without exhaustive analysis (Risely, 2023). These decisions, though seemingly spontaneous, were grounded in deep contextual knowledge and pattern recognition.

Importantly, intuitive decision making is most effective among experts with extensive domain experience. Novices, lacking the necessary mental models and situational awareness, are more prone to errors when relying solely on gut feelings (Kahneman & Klein, 2009). Therefore, organizations should view intuition not as guesswork, but as a legitimate and trainable competency—especially when paired with reflective practice and feedback mechanisms.

Making Creative Decisions

Creative decision making is a vital complement to rational, bounded rationality, and intuitive models of decision making. It involves generating novel and imaginative ideas that can lead to innovative solutions. In today’s competitive and fast-paced business environment, creativity is essential for addressing challenges such as cost reduction, product development, and strategic transformation (Clark & Schofield, 2023). While creativity is the spark that ignites innovation, it is not synonymous with innovation itself. Innovation requires the additional steps of planning, testing, and implementation. For instance, Dyson’s development of the bladeless fan began with a creative insight into airflow mechanics and evolved through rigorous engineering and market testing (Indeed Editorial Team, 2025).

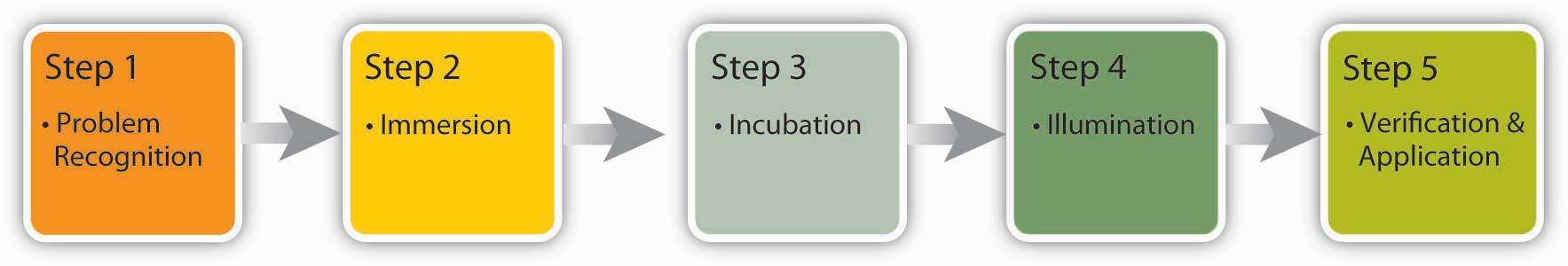

The creative decision-making process typically unfolds in five stages: problem identification, immersion, incubation, illumination, and verification/application. First, the decision maker must recognize a problem or opportunity—without this awareness, no solution can be pursued. Next, immersion involves gathering information and deeply engaging with the issue, often requiring domain-specific expertise. The third stage, incubation, is a period of subconscious processing where the problem is set aside, allowing the brain to unconsciously explore possibilities. This leads to illumination, the “aha” moment when a solution suddenly becomes clear—often in unexpected settings. A modern example includes the development of Post-it Notes, which emerged from a failed adhesive experiment at 3M but was later recognized as a solution for temporary note-taking (Study.com, 2023). Finally, the verification and application stage involves testing the idea’s feasibility and implementing it in practice.

Creative decision making is not limited to product design or marketing. It has been applied in crisis management, such as when a restaurant damaged by a storm pivoted to delivery and social media marketing to maintain revenue during repairs (Indeed Editorial Team, 2025). Similarly, airlines have used creative strategies like optimizing aircraft usage and renegotiating vendor contracts to increase profits without raising ticket prices. These examples highlight how creativity can lead to practical, impactful decisions across industries.

Ultimately, creative decision making thrives in environments that encourage curiosity, collaboration, and psychological safety. It is most effective when paired with analytical thinking and supported by a culture that values experimentation and learning from failure.

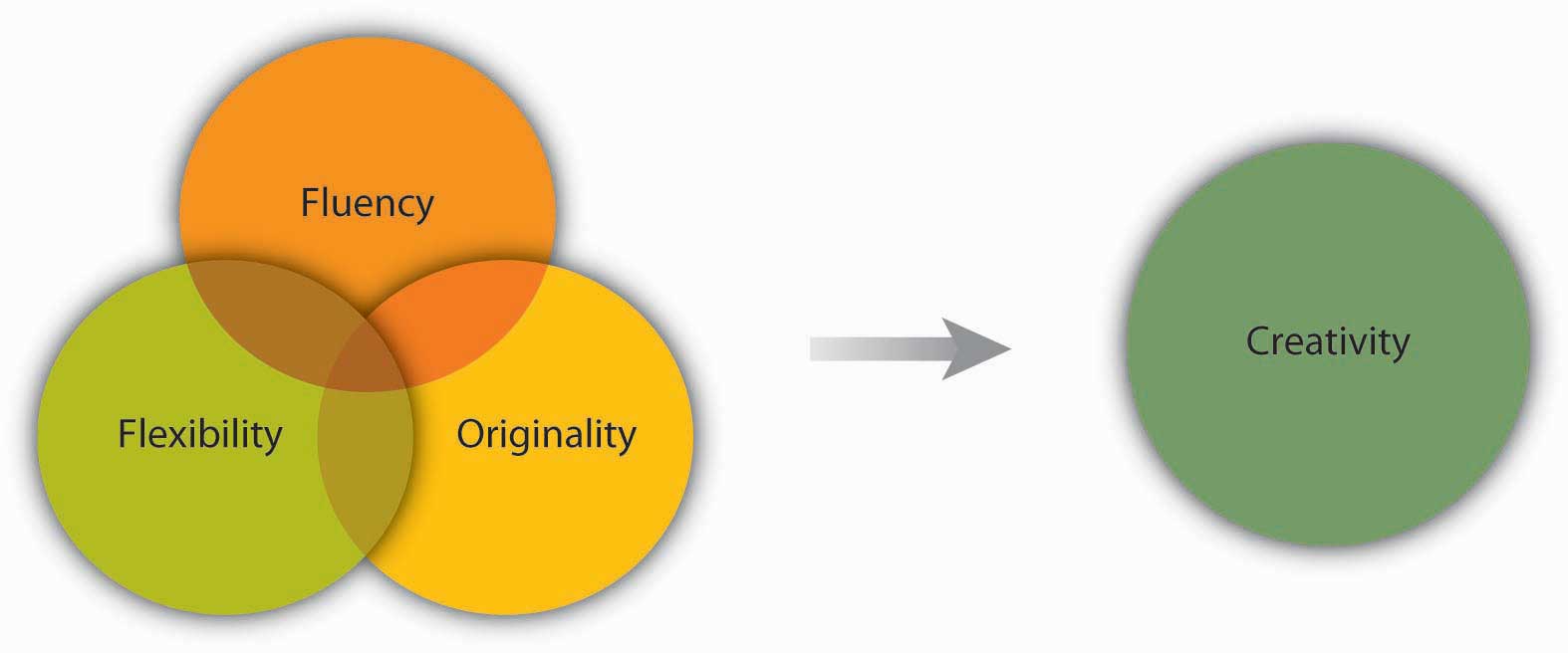

How Do You Know If Your Decision-Making Process Is Creative?

Creativity in decision making can be evaluated through three key dimensions: fluency, flexibility, and originality. Fluency refers to the number of ideas generated, flexibility reflects the diversity of those ideas, and originality measures how novel or unique the ideas are (Clark & Schofield, 2023). A highly creative decision-making process will produce numerous, varied, and distinctive solutions to a given problem. For example, Elon Musk’s ventures—from electric vehicles to space exploration—demonstrate high levels of flexibility and originality, as each initiative tackles different industries with unconventional approaches.

Creativity is not solely a product of spontaneous inspiration; it emerges from the interaction of individual traits, personal attributes, and environmental factors. Researchers have found that personality traits such as openness to experience and risk tolerance, combined with attributes like expertise, imagination, and intrinsic motivation, contribute significantly to creative output (Amabile, 1988; Feist, 1998). Moreover, situational factors—such as time pressure, encouragement from peers, and access to stimulating environments—can either enhance or inhibit creativity (Amabile et al., 1996; Tierney et al., 1999).

One widely used technique to foster creativity is brainstorming, which encourages the free flow of ideas without immediate judgment. Guidelines include suspending criticism, welcoming wild suggestions, and building on others’ ideas (Scott, Leritz, & Mumford, 2004). Research shows that setting high idea quotas during brainstorming sessions leads to better outcomes, as quantity often breeds quality (Study.com, 2023). A variation known as wildstorming pushes participants to explore seemingly impossible ideas and reverse-engineer ways to make them feasible—a method that has inspired breakthroughs in fields like biotech and sustainable design.

As Nobel laureate Linus Pauling famously said, “The best way to have a good idea is to have a lot of ideas.” This philosophy underscores the importance of cultivating environments that support divergent thinking and experimentation. Whether through structured techniques like SCAMPER or informal ideation sessions, organizations that prioritize creative decision making are better equipped to navigate uncertainty and drive innovation.

Final Thought

Creative decision making is not a luxury—it’s a necessity in today’s dynamic and competitive world. The ability to generate fluent, flexible, and original ideas empowers individuals and organizations to solve problems in innovative ways and adapt to rapid change. Whether it’s launching a disruptive business model, rethinking a manufacturing process, or responding to an unforeseen crisis, creativity transforms potential into performance. By understanding the traits, attributes, and environments that nurture creative thinking, decision makers can intentionally cultivate their own creative capacities and foster a culture that supports experimentation and growth. Ultimately, creativity is not just about having good ideas—it’s about having the courage and tools to turn imagination into action.

Figure 11.8

| Model | Use This Model When… |

|---|---|

| 🔍 Rational | – Alternatives can be quantified<br>- The decision is important<br>- You aim to maximize the outcome |

| ⛓️ Bounded Rationality | – Minimum criteria are clear<br>- Time/resources are limited<br>- A satisfactory outcome is acceptable |

| 🌪️ Intuitive | – Goals are unclear<br>- Time pressure makes deep analysis impractical<br>- You have experience with the issue |

| 🎨 Creative | – Solutions are not obvious<br>- New ideas must be generated<br>- You have time to explore and reflect |

Workplace Strategy Pack

Enhancing Organizational Creativity

Objective: To equip managers with evidence-based strategies for fostering creativity across individual, team, and organizational levels, thereby driving innovation, engagement, and competitive advantage.

Why It Matters

Creativity is no longer a luxury—it’s a strategic imperative. In today’s fast-paced, complex environments, organizations must continuously generate novel ideas to adapt, innovate, and thrive. Research shows that creativity contributes to:

- Improved problem-solving and decision-making

- Greater employee engagement and satisfaction

- Enhanced organizational reputation and adaptability

- Competitive differentiation in dynamic markets

Organizational creativity is shaped by leadership, communication, culture, and structural design—not just individual talent (Reiter-Palmon et al., 2019; Khalid et al., 2024).

Strategy Toolkit: Boosting Creativity in Your Organization

1. Cultivate Psychological Safety

- Encourage risk-taking without fear of punishment

- Normalize failure as part of the innovation process

- Model vulnerability and openness as a leader

2. Promote Symmetrical Internal Communication

- Ensure two-way communication between leadership and employees

- Use feedback loops to validate ideas and concerns

- Empower employees to advocate for their creative contributions (Khalid et al., 2024)

3. Build Diverse, Cross-Functional Teams

- Diversity in background, expertise, and thinking styles fuels creativity

- Rotate team members to expose them to new perspectives

- Use structured brainstorming and design thinking sessions

4. Set Clear Expectations for Creativity

- Include creativity in performance goals and evaluations

- Recognize and reward creative contributions

- Provide autonomy in how tasks are approached

5. Use Creative Aids and Tools

- Implement idea management platforms (e.g., digital suggestion boxes)

- Use visual mapping tools like mind maps or concept boards

- Offer training in creative problem-solving techniques

6. Foster a Creative Climate

- Design physical spaces that inspire (e.g., flexible work zones, art, natural light)

- Schedule “innovation hours” or “hack days”

- Encourage informal collaboration and spontaneous idea sharing

Empowerment Tip

Creativity isn’t confined to the “creative department.” Every employee has the potential to innovate when given the right environment, encouragement, and tools. As a manager, your role is to unlock that potential—not control it.

References

Khalid, J., Mi, C., Ashraf, M. U., & Islam, M. S. (2024). Leadership internal communication and employee creativity: Role of symmetrical communication, employee advocacy, and proactive personality. Global Knowledge, Memory and Communication. https://doi.org/10.1108/GKMC-10-2023-0385

Reiter-Palmon, R., Mitchell, K. S., & Royston, R. (2019). Improving creativity in organizational settings: Applying research on creativity to organizations. In J. C. Kaufman & R. J. Sternberg (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of creativity (2nd ed., pp. 515–545). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781316979839.026

Amabile, T. M. (1997). Motivating creativity in organizations: On doing what you love and loving what you do. California Management Review, 40(1), 22–26.

Fetrati, M. A., Hansen, D., & Akhavan, P. (2022). How to manage creativity in organizations: Connecting the literature on organizational creativity through bibliometric research. Technovation, 115, Article 102473. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2022.102473

Insider Edge

Thriving Under Uncreative Decision-Makers

Objective

To equip employees with strategies to navigate and influence decision-making when working under a manager or team lead who consistently demonstrates low creativity and poor judgment.

Why It Matters

Uncreative and ineffective decision-making at the leadership level can stifle innovation, reduce team morale, and hinder organizational agility. Employees who feel disempowered by poor leadership may disengage, leading to lower productivity and higher turnover. However, research shows that empowered employees can influence upward communication and foster change from within (Detert & Edmondson, 2011).

Strategy Toolkit

| Tactic | Description |

|---|---|

| Upward Communication | Use respectful, evidence-based feedback to share ideas and concerns with leadership (Ashkanasy et al., 2014). |

| Boundary Spanning | Collaborate across teams to bring in fresh perspectives and bypass bottlenecks (Marrone, 2010). |

| Shadow Leadership | Informally lead initiatives by modeling creative problem-solving and decision-making (Spreitzer, 1995). |

| Decision Framing | Reframe problems and present options in ways that highlight innovation and minimize risk aversion. |

| Peer Coalition Building | Build alliances with colleagues to support and amplify creative solutions. |

Empowerment Tip

Use the Creative Decision-Making Model yourself—even if your manager doesn’t. Immerse yourself in the problem, generate new solutions, and present them in a way that aligns with organizational goals. When leaders see initiative paired with strategic thinking, they’re more likely to adopt new approaches.

“Voice is not just about speaking up—it’s about being heard and making a difference.” — Detert & Burris (2007)

References

Ashkanasy, N. M., Humphrey, R. H., & Huy, Q. N. (2014). Integrating emotions and affect in theories of management. Academy of Management Review, 39(3), 366–376. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2012.0273

Detert, J. R., & Burris, E. R. (2007). Leadership behavior and employee voice: Is the door really open? Academy of Management Journal, 50(4), 869–884. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2007.26279183

Detert, J. R., & Edmondson, A. C. (2011). Impediments to speaking up about problems in healthcare. Harvard Business Review, 89(7–8), 60–65.

Marrone, J. A. (2010). Team boundary spanning: A multilevel review of past research and proposals for the future. Journal of Management, 36(4), 911–940. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206309353945

Spreitzer, G. M. (1995). Psychological empowerment in the workplace: Dimensions, measurement, and validation. Academy of Management Journal, 38(5), 1442–1465. https://doi.org/10.5465/256865

Discussion Questions

- What differentiates a successful decision from an unsuccessful one in your view? Consider how factors like timing, expertise, intuition, and creativity contribute to outcomes. How much do luck and skill interact in decision-making success, and what indicators help determine success over time?

- Studies show that more than half of organizational decisions fail (Burke & Miller, 1999; Kahneman & Klein, 2009). Does this finding surprise you? What do you think contributes most to this high failure rate—flawed processes, limited creativity, insufficient data, or something else?

- Have you applied the rational decision-making model in a personal, professional, or academic context? Walk through the problem identification, information gathering, and evaluation steps. Was the outcome satisfying, and how did this method compare to more intuitive or creative styles?

- Describe a time you engaged in satisficing—selecting a “good enough” solution rather than the optimal one. What constraints influenced this choice (e.g., time pressure, limited options)? Were you content with the result, and when do you think satisficing is most appropriate?

- How is intuition perceived as a decision-making method in your environment (workplace, school, etc.)? Do you believe it deserves more respect as a valid approach, particularly among experts? What conditions make intuitive decision making more reliable?

- How do you assess creativity in your own decision-making process? Think about fluency, flexibility, and originality. Have you ever had an “aha” moment similar to the illumination stage? What strategies or environments best support your creative thinking?

- Brainstorming and wildstorming are two techniques used to enhance idea generation. Have you participated in either? Which method did you find more effective, and how did it influence the final decision outcome?

Section 11.3: Recognizing and Avoiding Faulty Decision Making

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, you should be able to do the following:

- Define overconfidence bias and assess its influence on individual judgment and organizational risk-taking, using current examples from healthcare, finance, and consumer behavior; apply tools such as decision audits and reflective questioning to prevent inflated confidence.

- Identify hindsight bias and evaluate its impact on post-event assessments and accountability, particularly in contexts such as performance reviews, legal evaluations, and crisis response; implement practices that encourage contextual awareness and fair retrospective analysis.

- Explain anchoring bias and analyze how initial information can disproportionately shape decisions, with examples from negotiations, emergency responses, and marketing; apply reframing techniques and multi-data review strategies to improve judgment accuracy.

- Describe framing bias and investigate how language and presentation influence decision-making, using organizational examples from healthcare communication, branding, and strategic messaging; practice crafting neutral and balanced framing to support rational choices.

- Assess escalation of commitment and determine its role in failed investments and long-term projects, referencing cases like the Iridium launch and St. Louis Delmar Loop Trolley; design review checkpoints, exit criteria, and collaborative evaluation methods to prevent sunk-cost traps.

Even the most experienced professionals and collaborative teams can fall prey to subtle psychological traps that derail sound judgment. Decision making is not just a matter of logic and strategy—it’s shaped by cognitive limitations, social dynamics, and contextual pressures. As organizations strive for agility and clarity, understanding how and why decision-making errors occur has become essential for leaders, communicators, and teams alike.

This section explores common biases and pitfalls that lead to faulty decisions, including overconfidence, hindsight bias, anchoring, framing effects, and escalation of commitment—all of which can distort perception and obstruct rational analysis (Bazerman & Moore, 2013). In addition, we’ll expand the conversation to include confirmation bias, availability heuristic, authority bias, and groupthink, which often operate beneath the surface of team discussions and organizational processes (Kahneman, 2011; Janis, 1982).

By recognizing these traps and learning tools to avoid them—such as decision audits, dissent-friendly communication climates, and structured reflection—individuals and organizations can protect themselves from preventable missteps. Whether you’re making a budgetary choice, hiring decision, strategic pivot, or ethical judgment, becoming aware of these biases empowers you to think critically, act intentionally, and lead more effectively.

Avoiding 8 Decision-Making Traps

No matter which model you use, it is important to know and avoid the decision-making traps that exist. Daniel Kahnemann (another Nobel Prize winner) and Amos Tversky spent decades studying how people make decisions. They found that individuals are influenced by overconfidence bias, hindsight bias, anchoring bias, framing bias, and escalation of commitment.

1. Overconfidence Bias

Overconfidence bias occurs when individuals overestimate their knowledge, skills, or ability to predict future events. This cognitive distortion is widespread and can lead to poor decision-making across personal, professional, and societal domains. For instance, despite overwhelming evidence that human error contributes to over 90% of car accidents, a majority of U.S. drivers—about 73%—still rate themselves as better-than-average behind the wheel (Scribbr, 2025). This statistical impossibility illustrates the classic “better-than-average” effect, a hallmark of overconfidence bias.

In healthcare, overconfidence can have serious consequences. A recent study found that medical practitioners overestimated the probability of disease diagnoses by two to ten times compared to scientific evidence, both before and after testing (Morgan et al., 2021). This inflated certainty can lead to misdiagnoses, unnecessary treatments, and increased patient risk.

Financial decision-making is another arena where overconfidence bias thrives. Traders often believe they can outsmart the market, leading to risky investments. A modern example includes the collapse of Archegos Capital Management in 2021, where excessive leverage and misplaced confidence in stock positions led to billions in losses across global banks (Scribbr, 2025). Similarly, the infamous case of Jérôme Kerviel at Société Générale in 2008 remains a cautionary tale—his unchecked confidence in his trading strategies resulted in over $7 billion in losses, despite no personal financial gain (The rogue rebuttal, 2008).

Even everyday behaviors reflect this bias. Sports fans who confidently predict their team’s victory despite poor performance records, or individuals who believe they can replicate complex recipes without instructions, often fall prey to overconfidence (Helpful Professor, 2023). Lottery ticket buyers may also exhibit this bias, ignoring statistical improbability in favor of misplaced optimism. As Orkin (1991) noted, a person is three times more likely to die in a car accident driving to buy a ticket than to win the jackpot.

Overconfidence also undermines negotiation outcomes. Research shows that individuals who overestimate their leverage or persuasive ability tend to achieve less favorable results (Neale & Bazerman, 1985). To mitigate this bias, it’s essential to pause and critically evaluate whether your judgments are grounded in reality or inflated by self-assurance.

2. Hindsight Bias

Hindsight bias, often described as the “I knew it all along” effect, occurs when individuals perceive past events as more predictable than they actually were. This bias leads people to believe that outcomes were foreseeable, even when they were not, and it often distorts memory and judgment (Cherry, 2024). Unlike overconfidence bias, which inflates expectations before an event, hindsight bias reshapes perceptions after the fact—making mistakes seem obvious in retrospect.

This bias becomes particularly problematic when evaluating others’ decisions. For example, consider a company driver who hears an unusual engine noise before beginning the day’s route. Familiar with the vehicle, the driver assesses the sound as non-threatening and proceeds with the routine. Later, the car breaks down miles from the office. In hindsight, it may seem clear that the driver should have taken the vehicle in for service. However, the decision was based on prior experience and available information at the time, making the judgment reasonable in context. Hindsight bias can unfairly influence how we assign blame or assess competence in such scenarios.

Modern examples of hindsight bias are abundant. In the business world, failed product launches often trigger retrospective claims that the warning signs were obvious. After the collapse of Quibi, a short-form video streaming service, critics argued that its failure was predictable due to market saturation and poor timing—despite widespread investor enthusiasm beforehand (Scribbr, 2025). Similarly, in sports, fans frequently engage in “Monday morning quarterbacking,” insisting they knew a team would lose after witnessing the outcome, even if their pre-game predictions were uncertain (Nikolopoulou, 2023).

Medical malpractice cases also illustrate hindsight bias. Jurors may judge a physician’s decision harshly based on information revealed after the fact, rather than considering the limited data available at the time of diagnosis (Scribbr, 2023). This can lead to unfair assessments and legal consequences rooted more in retrospective clarity than in real-time reasoning.

To counteract hindsight bias, decision makers should document their thought processes, consider alternative outcomes, and avoid overestimating the predictability of events. Recognizing this bias helps foster empathy, improve judgment, and support fair evaluations of others’ actions.

3. Anchoring

Anchoring bias refers to the cognitive tendency to rely too heavily on an initial piece of information—known as the “anchor”—when making decisions. This bias can distort judgment, especially when individuals fail to adequately adjust their thinking after receiving new or conflicting information (Nikolopoulou, 2025).

In job negotiations, anchoring often manifests when candidates fixate on a specific salary figure, ignoring other critical aspects of the offer such as benefits, work-life balance, and organizational culture. For example, a candidate anchored to a $70,000 salary may overlook a $65,000 offer that includes generous healthcare, remote flexibility, and professional development opportunities (Scribbr, 2025).

Anchoring bias also plays a significant role in consumer behavior. Retailers frequently use high “suggested retail prices” to anchor perceptions of value, making discounted prices appear more attractive—even if the final price remains inflated (Cornell, 2024). Similarly, subscription services often list premium packages first to make mid-tier options seem like better deals by comparison.

In high-stakes environments, anchoring can have life-threatening consequences. A tragic example occurred during the Great Bear Wilderness Disaster, where a coroner prematurely declared all passengers of a crashed plane dead within minutes of arriving at the scene. Anchored by the visual devastation and flames, the coroner halted search efforts—only for two survivors to emerge the following day (Becker, 2007). This case underscores how anchoring can override critical thinking, especially under pressure.

Legal systems are not immune to anchoring either. Research shows that judges may issue longer sentences when prosecutors suggest high penalties, even if the recommendation lacks merit. This anchoring effect persists even among experienced judges, revealing how initial figures can skew supposedly objective decisions (Englich & Mussweiler, 2001).

To counter anchoring bias, decision makers should delay judgment, seek multiple data points, and use structured decision-making frameworks. Awareness of anchoring’s influence is the first step toward more rational and equitable choices.

4. Framing Bias

Framing bias refers to the cognitive tendency for individuals to be influenced by how information is presented rather than the actual content itself. This bias can lead to irrational or suboptimal decisions, especially when the framing evokes emotional responses or distorts perceived value (Tversky & Kahneman, 1981). For example, consumers are more likely to accept a “10% discount” than a “$10 reduction,” even if both result in the same final price—because percentage framing feels more generous (Cornell, 2024).

Marketing and advertising frequently exploit framing bias. A product labeled “90% fat-free” is often perceived more positively than one labeled “10% fat,” despite the identical nutritional content (Nikolopoulou, 2025). Similarly, restaurants may describe a dish as “locally sourced and organic” rather than “expensive and small-portioned,” even if both are true. These subtle shifts in language can dramatically alter consumer behavior.

In healthcare, framing bias can influence treatment decisions. Patients are more likely to opt for a procedure described as having a “90% survival rate” than one with a “10% mortality rate,” even though both convey the same statistical outcome (Cognitive Bias Lab, 2025). This effect underscores the importance of neutral, balanced communication in medical contexts.

Investing decisions are also vulnerable. Investors may be drawn to a fund described as “beating the market by 5% last year” rather than one that “underperformed in two of the last five years,” even if both statements are factually accurate (Investopedia, 2023). The positive framing of short-term gains can overshadow long-term volatility.

To mitigate framing bias, decision makers should rephrase information in multiple formats, seek objective data, and consider both positive and negative frames before making judgments. Awareness of this bias empowers individuals to make more rational, informed choices.

5. Escalation of Commitment

Escalation of commitment occurs when individuals or organizations continue investing in a failing course of action despite mounting evidence that it is no longer viable. Often referred to as the “sunk cost fallacy,” this bias leads decision makers to justify continued investment based on prior expenditures rather than future value (Wong & Kwong, 2007).

A relatable example is the used car that constantly requires repairs. Rather than cutting losses by selling or donating the vehicle, many people continue pouring time and money into it, hoping to recover their initial investment. This behavior reflects emotional attachment and a reluctance to admit a poor decision.

A corporate illustration of this bias is Motorola’s Iridium project. Initially conceived in the 1980s to solve global communication gaps, the project involved launching 66 satellites to enable worldwide phone coverage. Although the idea was groundbreaking at the time, by the late 1990s, cell phone technology had evolved rapidly, rendering Iridium obsolete. Nevertheless, Motorola released the $3,000 Iridium phone in 1998—despite its impractical size and limited usability. The project ultimately failed, leading to bankruptcy in 1999 after $5 billion in development costs (Finkelstein & Sanford, 2000).

A more recent and local example is the St. Louis Delmar Loop Trolley. Originally envisioned as a nostalgic and tourist-friendly transit system, the trolley received over $50 million in funding, including $37 million in federal grants. Despite years of delays, low ridership, and mounting operational costs, city leaders continued to invest in the project to avoid repaying federal funds and to preserve future grant eligibility (Siemers, 2021). The trolley’s limited route, outdated vehicles, and lack of integration with broader transit systems contributed to its failure. Yet, efforts to revive it persist, illustrating how sunk costs and political pressure can fuel escalation of commitment—even when public sentiment and economic logic suggest otherwise.

Escalation of commitment often stems from two key psychological drivers: the reluctance to admit error and the belief that additional investment might reverse losses. To counter this bias, decision makers should establish clear exit criteria, assign independent evaluators, and conduct periodic reviews of long-term projects. Cultivating a culture that normalizes course correction can also reduce the stigma of changing direction and promote more rational decision-making.

6. Confirmation Bias

Confirmation bias refers to the tendency to seek, interpret, and remember information that supports one’s preexisting beliefs while disregarding contradictory evidence. In organizational settings, this bias can quietly shape decisions, reinforce flawed strategies, and stifle innovation (Healy, 2019). Leaders may selectively highlight data that supports their vision while ignoring warning signs, creating echo chambers that hinder adaptive thinking (Gebreamlak, 2025).

For example, a CEO convinced of a product’s success may direct market research to validate their assumptions rather than explore genuine consumer needs. This bias can also affect hiring decisions—HR professionals may favor candidates who align with their initial impressions, overlooking red flags or alternative talent (Japs, 2024). In performance evaluations, confirmation bias can lead managers to overemphasize positive traits in favored employees while minimizing shortcomings, resulting in skewed assessments and missed opportunities for growth (Brady, 2024).

To counter confirmation bias, organizations can appoint devil’s advocates during strategic reviews, conduct blind evaluations, and encourage dissent-friendly cultures. Regular audits and third-party assessments also help challenge internal narratives and promote balanced decision-making (Alonso, 2025).

7. Availability Heuristic

The availability heuristic is a mental shortcut where individuals judge the likelihood of events based on how easily examples come to mind—especially if those examples are vivid or emotionally charged (Hoffman, 2024). In organizational communication, this bias can distort risk perception and decision-making, particularly in high-pressure environments.

For instance, after a high-profile cybersecurity breach, executives may overestimate the likelihood of similar attacks and overinvest in security tools, while neglecting other pressing vulnerabilities. Conversely, if a risk hasn’t been recently publicized, it may be underestimated—even if statistically more probable (Lee, 2025). This bias also influences hiring and performance reviews, where recent dramatic incidents may overshadow long-term patterns.

In marketing and leadership communication, emotionally resonant stories often outweigh data-driven insights. While storytelling is powerful, it can inadvertently reinforce availability bias if not balanced with empirical evidence (Kim, 2013).

To mitigate this bias, organizations should rely on diverse data sources, encourage critical thinking, and frame risk messages with context and clarity. Decision-support systems and structured reflection can help teams evaluate risks more objectively.

8. Groupthink

Groupthink occurs when cohesive teams prioritize consensus over critical evaluation, leading to poor decisions and suppressed dissent (Janis, 1982). In organizational communication, groupthink can manifest in strategy meetings, crisis response, and hiring panels—especially when leaders discourage alternative viewpoints or when teams are insulated from external feedback (Choi & Kim, 1999).

A striking example is the St. Louis Delmar Loop Trolley project, which continued to receive funding despite low ridership and operational failures. Decision makers escalated commitment to avoid admitting error and to preserve future grant eligibility, even as public support waned (Siemers, 2021). This illustrates how groupthink can be fueled by sunk costs, political pressure, and fear of reputational damage.

Groupthink symptoms include illusions of unanimity, self-censorship, and pressure to conform. To prevent it, organizations can appoint devil’s advocates, encourage diverse perspectives, and conduct second-chance reviews before finalizing decisions (Akhmad et al., 2021). Cultivating psychological safety and dissent-friendly cultures helps teams challenge assumptions and make more resilient choices.

In the dynamic landscape of organizational decision-making, understanding cognitive biases is not just a psychological exercise—it’s a leadership imperative. From overconfidence and hindsight bias to anchoring, framing effects, and escalation of commitment, these mental shortcuts silently shape everyday choices, often at great cost. Biases such as confirmation bias, the availability heuristic, and groupthink can further distort team communication, amplify errors, and stifle innovation. Yet, by cultivating awareness, encouraging dissent, implementing structured reflection, and fostering psychologically safe environments, organizations can counteract these cognitive traps. Decision makers who learn to recognize and challenge bias not only sharpen their judgment but also strengthen their teams, empower diverse thinking, and drive more ethical, sustainable outcomes. Bias is human—but with intention and tools, better decisions are within reach.

Insider Edge

Helping Managers Avoid Decision-Making Traps

Objective: To empower managers with the awareness and tools needed to avoid cognitive and organizational decision-making traps that compromise effectiveness, creativity, and team trust.

Why It Matters

Decision-making traps—such as confirmation bias, groupthink, and overconfidence—can lead to flawed strategies, missed opportunities, and diminished team morale. Managers who fall into these traps may unintentionally suppress innovation and erode psychological safety. Research shows that transparent communication, diverse perspectives, and reflective practices significantly improve decision quality (Janis, 1982; Edmondson, 1999).

Strategy Toolkit

| Trap | Avoidance Strategy |

|---|---|

| Confirmation Bias | Encourage dissenting views and actively seek disconfirming evidence (Nickerson, 1998). |

| Groupthink | Promote psychological safety and assign a “devil’s advocate” role to challenge consensus (Janis, 1982). |

| Overconfidence | Use decision audits and post-mortems to assess accuracy and recalibrate judgment (Kahneman et al., 2011). |

| Anchoring | Delay judgment until multiple perspectives and data points are reviewed (Tversky & Kahneman, 1974). |

| Escalation of Commitment | Set clear exit criteria and encourage team input on whether to pivot or persist (Staw, 1981). |

Empowerment Tip

Use structured decision frameworks like the Rational or Creative Decision-Making Models to slow down impulsive choices and foster deliberate, inclusive thinking. Pair this with open communication channels to surface hidden risks and alternative viewpoints.

“The best decisions are not made in isolation—they emerge from dialogue, dissent, and reflection.” — Edmondson (1999)

References

Edmondson, A. (1999). Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44(2), 350–383. https://doi.org/10.2307/2666999

Janis, I. L. (1982). Groupthink: Psychological studies of policy decisions and fiascoes (2nd ed.). Houghton Mifflin.

Kahneman, D., Lovallo, D., & Sibony, O. (2011). Before you make that big decision… Harvard Business Review, 89(6), 50–60.

Nickerson, R. S. (1998). Confirmation bias: A ubiquitous phenomenon in many guises. Review of General Psychology, 2(2), 175–220. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.2.2.175

Staw, B. M. (1981). The escalation of commitment to a course of action. Academy of Management Review, 6(4), 577–587. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1981.4285694

Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1974). Judgment under uncertainty: Heuristics and biases. Science, 185(4157), 1124–1131. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.185.4157.1124

Discussion Questions

- Reflect on a time when you fell into one of the cognitive decision-making traps discussed (e.g., overconfidence, hindsight bias, anchoring, framing, escalation of commitment, confirmation bias, availability heuristic, or groupthink). How did your thinking change over time, and what eventually helped you recognize the bias? If relevant, connect your experience to one of the organizational examples mentioned (e.g., the Delmar Loop Trolley, hiring decisions, or product launches).

- What strategies can help individuals and organizations avoid escalation of commitment? Refer to examples like the Iridium project or the Delmar Loop Trolley to analyze what turning points or review practices might have interrupted the continued investment.

- Share a real-life example of anchoring bias you’ve encountered or observed. This might relate to salary negotiations, consumer pricing, courtroom decisions, or a situation where an initial impression overly shaped the final outcome.

- Which decision-making trap discussed in this section seems most dangerous in organizational settings—and why? Consider both individual-level traps (like overconfidence or confirmation bias) and group-level traps (like groupthink). How does this bias threaten communication, leadership, or strategic outcomes in your view?

Section 11.4: Decision Making in Groups and Teams

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, you should be able to do the following:

- Compare the advantages and limitations of individual versus group decision-making, including the role of cognitive diversity, psychological safety, and strategic context in shaping decision quality and implementation.

- Identify the symptoms and risks of groupthink, and evaluate its impact across hierarchical roles; apply strategies to foster dissent, reduce conformity pressure, and promote ethical decision-making in team environments.

- Select and apply appropriate decision-making tools and techniques such as Nominal Group Technique (NGT), Delphi, voting-based methods, consensus models, and analytical tools like decision trees, based on group size, decision complexity, and stakeholder needs.

- Evaluate the influence of technology-enhanced decision systems (e.g., GDSS, AI-assisted platforms) on team communication, information sharing, and decision outcomes; identify potential risks such as information overload, interface complexity, and psychological barriers to contribution.

- Analyze the role of conflict in decision-making and apply constructive conflict management strategies, including structured dialogue, emotional intelligence, and inclusive communication practices that support innovation and group cohesion.

When It Comes to Decision Making, Are Two Heads Better Than One?

The answer to this question depends on a variety of contextual factors. Group decision making offers distinct advantages, particularly in organizational settings where diverse perspectives, shared expertise, and collaborative problem-solving are valued. Research consistently shows that groups can outperform individuals when tasks require creativity, complex analysis, or integration of varied knowledge domains (Qudrat-Ullah, 2025). Diverse teams, especially those that encourage dissent and debate, tend to produce more comprehensive decisions and foster innovation (Keyton et al., 2022; Simons et al., 1999).

Moreover, group decision making can enhance member satisfaction and commitment. When individuals participate in the decision-making process, they are more likely to support and implement the final decision (Forsyth, 2018). This buy-in is particularly important in organizational contexts where decisions affect multiple stakeholders. Psychological safety and cognitive diversity—two increasingly emphasized constructs in contemporary research—further contribute to the effectiveness of group decisions by promoting open communication and reducing conformity pressures (Beck et al., 2022; Reimer et al., 2025).

However, group decision making is not without its drawbacks. Coordination challenges, social loafing, and decision-making biases such as groupthink can undermine the process (Gouran et al., 1986; Miner, 1984). Groups may also struggle with information sharing, especially when critical data is unevenly distributed or withheld—a phenomenon known as the hidden profile problem (Wittenbaum et al., 2004). Additionally, group decisions typically require more time and effort than individual ones, which can be a liability in time-sensitive situations.

Ultimately, the choice between individual and group decision making should be guided by the nature of the task, the urgency of the decision, and the availability of relevant expertise. Individual decision making may be preferable in emergencies or when one person possesses all necessary information. Conversely, group decision making is more effective when the task is complex, implementation requires broad support, and time allows for deliberation.

Groupthink and Decision-Making Biases

Groupthink: The Hidden Hazard in Organizational Decision Making

Groupthink is a psychological phenomenon that occurs when members of a decision-making group prioritize consensus over critical thinking. This can lead to a suppression of dissent and ultimately, flawed outcomes. First identified by Irving Janis (1972), groupthink manifests through several telltale symptoms, including illusions of invulnerability, collective rationalizations, moral righteousness, stereotyping outsiders, direct pressure on dissenters, self-censorship, perceived unanimity, and the presence of self-appointed “mindguards” who shield the group from conflicting information.

The dangers of groupthink extend across all levels of an organization. Superiors who fall prey to groupthink may become strategically blind, dismissing warnings or alternatives to maintain harmony. Their unquestioned belief in the group’s inherent morality can lead to ethically questionable decisions, as evidenced in high-profile corporate failures such as Enron (Sims & Brinkmann, 2003). Additionally, dominant leadership styles may unintentionally stifle creativity, discouraging alternative viewpoints and reducing innovation (Carmeli, Brueller, & Dutton, 2009).

For subordinates, groupthink can foster a culture of silence. Employees may avoid speaking out due to fear of reprisal or concern about being labeled as disruptive (Kassing, 2000). Over time, this can erode psychological safety, trust, and team engagement (Edmondson, 2018). Subordinates may also experience moral distress when they feel complicit in poor decisions simply because they withheld opposition.

Current organizational communication research suggests several strategies for counteracting groupthink. Cultivating psychological safety—where team members feel free to express ideas and concerns without fear—is critical to breaking conformity (Carmeli et al., 2009). Designating a devil’s advocate during meetings can also help surface alternative viewpoints (Janis, 1982). Moreover, diverse teams, especially those with heterogeneous backgrounds and experiences, are more likely to challenge assumptions and engage in critical debate (Tetlock et al., 1992). Leadership style plays a pivotal role: when leaders refrain from expressing strong preferences early in the decision-making process, it fosters a more open exchange of ideas and reduces the risk of undue influence (Esser, 1998).

Ultimately, recognizing and addressing groupthink is essential to improving organizational decision making. By encouraging dissent, supporting diverse perspectives, and creating a psychologically safe environment, both leaders and team members can avoid the pitfalls of consensus-at-any-cost thinking.

Workplace Strategy Pack

Breaking Free from Groupthink

Objective

To equip managers and employees with the knowledge, tools, and communication strategies needed to identify and prevent groupthink, fostering a culture of open dialogue, critical thinking, and innovation.

Why It Matters

Groupthink occurs when teams prioritize harmony and consensus over critical evaluation, often leading to poor decisions, missed risks, and suppressed dissent. It thrives in environments lacking psychological safety, diverse perspectives, or structured decision protocols. Preventing groupthink is essential for organizational resilience, ethical decision-making, and adaptive leadership (Janis, 1982; Edmondson, 1999).

Strategy Toolkit

| Strategy | Application |

|---|---|

| Establish Psychological Safety | Encourage open dialogue, admit mistakes, and reward constructive dissent (Edmondson, 1999). |

| Assign Devil’s Advocates | Rotate team members to challenge assumptions and present alternative viewpoints (Nemeth, 1986). |

| Use Structured Decision Models | Apply Rational or Creative models to slow down consensus and evaluate options systematically. |

| Encourage Independent Thinking | Have individuals write down ideas before group discussion to reduce conformity pressure (Paulus & Nijstad, 2003). |

| Diverse Team Composition | Include members with varied backgrounds and expertise to broaden perspectives (Williams & O’Reilly, 1998). |

| Anonymous Input Channels | Use surveys or digital platforms to collect candid feedback without social pressure. |

Empowerment Tip

Whether you’re leading or contributing, speak up early and often—especially when something feels off. Research shows that even one dissenting voice can disrupt groupthink and lead to better outcomes (Nemeth, 1986). If you’re unsure how to raise concerns, frame your input as a question or scenario: “What if we considered X?” or “How might this play out if Y happens?”

“Silence in teams is rarely a sign of agreement—it’s often a symptom of fear.” — Edmondson (1999)

References

Edmondson, A. (1999). Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44(2), 350–383. https://doi.org/10.2307/2666999

Janis, I. L. (1982). Groupthink: Psychological studies of policy decisions and fiascoes (2nd ed.). Houghton Mifflin.

Nemeth, C. J. (1986). Differential contributions of majority and minority influence. Psychological Review, 93(1), 23–32. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.93.1.23

Paulus, P. B., & Nijstad, B. A. (2003). Group creativity: Innovation through collaboration. Oxford University Press.

Williams, K. Y., & O’Reilly, C. A. (1998). Demography and diversity in organizations: A review of 40 years of research. Research in Organizational Behavior, 20, 77–140.

Psychological Safety: The Cornerstone of Effective Team Communication

In today’s dynamic and increasingly collaborative work environments, psychological safety has emerged as a foundational element for high-performing teams. Defined as a shared belief that individuals can express ideas, ask questions, admit mistakes, and challenge the status quo without fear of humiliation or retaliation, psychological safety fosters open communication and trust (Edmondson, 2018). It is not about being perpetually comfortable—it’s about feeling secure enough to engage in uncomfortable but necessary conversations that drive learning and innovation.

Research has consistently shown that psychological safety enhances team learning, creativity, and productivity. For example, Google’s Project Aristotle identified psychological safety as the most critical factor distinguishing successful teams from less effective ones (Williams, 2025). Teams that feel safe are more likely to report errors, share feedback, and experiment with new ideas—behaviors that are essential for continuous improvement and adaptability (Duncan, 2025).

Importantly, psychological safety is not a passive climate but an actively cultivated culture. Leaders play a pivotal role in setting the tone by modeling vulnerability, inviting participation, and responding thoughtfully to input (Lynn, 2025). Neuroscience-based strategies suggest that when leaders set clear expectations, encourage diverse perspectives, and reward candid dialogue, they activate reward pathways in the brain that reinforce open communication and collaborative behavior (Lynn, 2025).

The absence of psychological safety can have serious consequences. Teams may fall into silence, avoid risk-taking, and suppress dissenting views—conditions that stifle innovation and increase the likelihood of groupthink. Moreover, marginalized employees or those with less positional power often experience lower levels of psychological safety, which can exacerbate inequities and reduce engagement (Crossan, 2025).

To build and sustain psychological safety, organizations must go beyond surface-level interventions. This includes fostering character-based leadership, promoting inclusive dialogue, and embedding safety into everyday practices such as feedback, decision-making, and conflict resolution (Crossan, 2025). When psychological safety is present, teams are not only more effective—they are more resilient, inclusive, and capable of navigating complexity with confidence.

Cognitive Diversity: A Strategic Advantage in Team Decision Making

Cognitive diversity refers to the differences in how individuals think, process information, and approach problem solving. Unlike demographic diversity, which focuses on visible traits such as race, gender, or age, cognitive diversity encompasses variations in mental models, analytical styles, and decision-making preferences (Klein et al., 2023). These differences may arise from educational backgrounds, professional experiences, personality traits, or even cultural influences. In organizational contexts, cognitive diversity has gained recognition as a powerful driver of innovation, adaptability, and strategic insight.

Research shows that cognitively diverse teams are better equipped to challenge assumptions, identify blind spots, and generate creative solutions to complex problems (Barnhill, 2025; Reynolds & Lewis, 2022). For example, teams with varied thinking styles are more likely to avoid groupthink and engage in constructive debate, leading to more robust and well-rounded decisions. A study by Cloverpop found that inclusive teams make better decisions up to 87% of the time and deliver 60% stronger outcomes when cognitive diversity is actively leveraged (Reynolds & Lewis, 2022).

However, cognitive diversity is not without its challenges. Teams with highly divergent cognitive styles may experience communication barriers, coordination difficulties, and reduced cohesion (Aggarwal et al., 2019). These issues can be exacerbated when psychological safety is lacking, as individuals may hesitate to share unconventional ideas or question dominant viewpoints (Edmondson, 2018). In fact, research suggests that the benefits of cognitive diversity are most pronounced in environments where team members feel safe to express themselves and engage in open dialogue (Edmans, 2025).

To harness the full potential of cognitive diversity, organizations must intentionally cultivate inclusive cultures and adaptive leadership practices. This includes recruiting for diverse thinking styles, designing onboarding programs that promote mutual understanding, and training leaders to recognize and respond to varied cognitive preferences (Barnhill, 2025). When paired with psychological safety, cognitive diversity becomes a strategic asset—fueling innovation, enhancing decision quality, and equipping teams to navigate uncertainty with agility.

7 Tools and Techniques for Making Better Decisions

1. Structured Idea Generator Techniques: The Nominal Group Technique

The Nominal Group Technique (NGT) is a structured method designed to enhance group decision making by ensuring equitable participation and minimizing dominance by more vocal members. Originally developed by Delbecq, Van de Ven, and Gustafson (1975), NGT is particularly effective in settings where teams are tasked with solving complex problems or generating innovative ideas. It is not intended for routine meetings but is best employed when diverse input and consensus are critical.

NGT unfolds through a series of deliberate steps. First, participants silently and independently generate ideas in response to a clearly defined question or problem. This initial phase encourages reflection and reduces the influence of group dynamics on individual thinking. Second, in a round-robin format, each member shares one idea at a time, ensuring that all contributions are heard and recorded without immediate critique. Third, the group engages in a structured discussion to clarify, elaborate, and evaluate the ideas presented. This phase promotes deeper understanding and allows for the integration of perspectives. Finally, participants privately rank or rate the ideas, and the results are compiled to identify the most favored options.

Contemporary research highlights NGT’s value in promoting psychological safety, encouraging contributions from quieter members, and reducing the risk of groupthink (Vahedian-Shahroodi et al., 2023; Edmondson, 2018). It is especially useful in diverse teams where power dynamics or communication barriers might otherwise inhibit open dialogue. By combining individual ideation with collective evaluation, NGT fosters inclusive decision making and leads to more balanced, innovative outcomes.

2. Remote and Expert-Based Decision Making: The Delphi Technique

The Delphi Technique is a structured, iterative method for gathering expert input and building consensus without requiring face-to-face interaction. Originally developed by the RAND Corporation in the 1950s as a forecasting tool, it has evolved into a widely used decision-making strategy across disciplines including healthcare, education, public policy, and organizational planning (Khodyakov et al., 2023). The technique is particularly valuable when decisions must be made under conditions of uncertainty or when geographically dispersed experts are involved.