Chapter 15: Organizational Culture

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, you should be able to do the following:

- Explain the concept of organizational culture and analyze its significance to organizational effectiveness.

- Identify and categorize the key dimensions that shape a company’s culture.

- Compare and contrast characteristics of weak and strong organizational cultures.

- Analyze the internal and external factors that contribute to the development of organizational culture.

- Evaluate strategies for cultural change and propose methods for implementing change effectively.

- Assess the relationship between organizational culture and ethical decision-making.

- Interpret cross-cultural variations in organizational culture and apply insights to global business contexts.

Section 15.1: Spotlight

Organizational Culture and Whistleblower Retaliation in St. Louis City Government

The St. Louis City Tow Lot and City Hall have come under intense scrutiny following revelations of systemic corruption and retaliation against whistleblowers. A 2025 city audit revealed that over $5 million in vehicles and $80,000 in cash were missing from the tow lot, with 33% of tow tickets either incomplete or falsified (KSDK, 2025). Whistleblowers such as Angelica Woods and George Hooker described a culture where “rules were made up as they went,” and employees who reported misconduct were transferred, demoted, or terminated (FOX2Now, 2025). These patterns reflect a deeply flawed organizational culture characterized by informal norms, lack of accountability, and resistance to transparency.

The tow lot exhibited a weak organizational culture where informal power structures and personal gain superseded formal policies. Employees reportedly set aside vehicles for friends and family, forged paperwork, and pocketed payments (Yahoo News, 2025). Meanwhile, City Hall’s culture—though more structured—enabled retaliation against whistleblowers, undermining Ordinance 70475, which was designed to protect employees reporting improper governmental action (City of St. Louis, 2017). The disconnect between policy and practice suggests a symbolic rather than substantive commitment to ethical governance.

Several factors contributed to this dysfunctional culture. Leadership failures—particularly within the Streets Department—allowed misconduct to persist unchecked (AOL, 2025). A lack of technological infrastructure (e.g., digital inventory and payment systems) enabled fraud and obscured accountability. Employees feared retaliation more than they trusted internal reporting mechanisms, eroding psychological safety. These conditions created a climate where silence and complicity were rewarded, and integrity was punished (FOX2Now, 2025).

To change the culture, both City Hall and the tow lot must prioritize transparency, accountability, and ethical leadership. Implementing digital systems, establishing independent oversight bodies, and enforcing whistleblower protections are essential. Leadership must model ethical behavior and cultivate a psychologically safe environment where employees can speak up without fear (City of St. Louis, 2025). Mandatory ethics and communication training across departments could reinforce these changes.

The relationship between ethics and culture is central to this case. Retaliating against whistleblowers not only violates ethical standards but signals that misconduct may be tolerated if it protects internal interests. This erosion of trust compromises public service and damages the city’s reputation. Moreover, cross-cultural impacts are evident in how whistleblowers from marginalized communities were treated—underscoring a lack of cultural competence in protecting diverse voices within city government (Yahoo News, 2025).

In conclusion, the St. Louis Tow Lot scandal and City Hall’s pattern of retaliation reveal a culture in urgent need of reform. Aligning ethical standards with behavior, implementing inclusive protections, and fostering transparency can begin to restore integrity in municipal operations.

References

City of St. Louis. (2017). Ordinance 70475: Whistleblower ordinance. https://www.stlouis-mo.gov/government/city-laws/ordinances/ordinance.cfm?ord=70475

City of St. Louis. (2025). Snow and ice response and maintenance. https://www.stlouis-mo.gov/government/departments/street/street-division/snow-ice/index.cfm

FOX2Now. (2025, May 7). ‘It was my livelihood’: Victim speaks out amid federal probe. https://fox2now.com/news/missouri/it-was-my-livelihood-victim-speaks-out-amid-federal-probe/

KSDK. (2025, May 5). $5 million in vehicles missing from St. Louis city tow lots. https://www.ksdk.com/article/news/local/st-louis-tow-lot-federal-corruption-probe-whistleblower-auctions-missing-cars/63-c6260f43-0483-4c00-997b-93a0b60f334e

Yahoo News. (2025, May 20). St. Louis tow lot investigation reveals systemic corruption. https://www.yahoo.com/news/st-louis-tow-lot-investigation-110100512.html

AOL. (2025, May 20). St. Louis tow lot investigation reveals systemic corruption. https://www.aol.com/finance/st-louis-tow-lot-investigation-110100382.html

Discussion Questions

- What specific elements of organizational culture contributed to the systemic corruption and retaliation against whistleblowers in the St. Louis City Tow Lot and City Hall? How could these elements have been addressed proactively?

- How does the concept of psychological safety relate to the whistleblower retaliation described in the case study? What steps can leaders take to foster a culture where employees feel safe reporting misconduct?

- In what ways did the lack of accountability and technological infrastructure at the tow lot reflect a weak organizational culture? How might implementing new systems and processes strengthen the culture?

- What role does leadership play in shaping ethical behavior and organizational culture? How could leadership at City Hall and the tow lot have acted differently to prevent these scandals?

- How do cross-cultural impacts, such as the treatment of whistleblowers from marginalized communities, influence the overall organizational culture? What strategies can organizations use to ensure inclusivity and equity in their culture?

Section 15.2: Understanding Organizational Culture

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, you should be able to do the following:

- Define organizational culture as a dynamic system of shared values, beliefs, assumptions, and communicative practices that shape employee behavior, workplace norms, and decision-making.

- Explain the strategic importance of organizational culture in enhancing performance, fostering innovation, navigating change, and promoting psychological safety and inclusion in modern work environments.

- Describe the three interrelated levels of organizational culture—artifacts, espoused values, and underlying assumptions—and analyze how these levels reveal cultural alignment, behavioral norms, and organizational priorities.

- Identify examples of cultural strengths and weaknesses, and evaluate how specific practices—such as inclusive rituals or rigid hierarchies—impact engagement, adaptability, and equity.

- Assess how organizational culture functions as a control mechanism, guiding employee behavior in ambiguous situations through shared meaning rather than formal policies.

Organizational culture refers to the shared system of values, beliefs, assumptions, and behavioral norms that shape how individuals interact, make decisions, and interpret their roles within a workplace. It is the invisible architecture that guides what is considered appropriate or inappropriate behavior, often without formal rules (Schein, 2017; Chatman & O’Reilly, 2016). While the concept gained prominence in the 1980s through works like In Search of Excellence (Peters & Waterman, 1982), recent scholarship emphasizes that culture is not static—it is continuously constructed and reconstructed through communication, rituals, and shared meaning-making (Khandelwal & Upadhyay, 2025).

Culture becomes most visible when individuals transition between organizations or compare cross-sector norms. For instance, one company may emphasize hierarchy, formal attire, and after-hours responsiveness, while another may prioritize psychological safety, casual dress, and flexible work boundaries. These differences reflect deeper cultural assumptions about power, time, and interpersonal dynamics (Schein, 2017). In hybrid and remote environments, digital artifacts—such as emoji use, Slack etiquette, and virtual onboarding rituals—now play a central role in shaping and signaling organizational culture (Fernandez Cruz, 2025).

Why Does Organizational Culture Matter?

Organizational culture is increasingly recognized as a strategic asset. A strong, adaptive culture can enhance performance, foster innovation, and serve as a source of competitive advantage—especially when it is difficult to replicate (Barney, 1986; McKinsey & Company, 2025). In PwC’s Global Culture Survey, 72% of respondents cited culture as critical to successful change initiatives, yet only 32% believed their culture was actively managed (PwC, 2021). This gap underscores the need for intentional culture stewardship.

Culture influences key performance indicators such as revenue growth, employee retention, and customer satisfaction. Kotter and Heskett (1992) found that companies with performance-enhancing cultures outperformed peers in stock price and net income over a decade. However, cultural fit with environmental demands is essential. A tech firm that values experimentation and agility will thrive, while one that clings to rigid procedures may falter in fast-moving markets (Arogyaswamy & Byles, 1987).

Beyond performance, culture acts as a behavioral compass. It guides decision-making in ambiguous situations and often supersedes formal policies. For example, a culture of customer-centricity empowers employees to prioritize client satisfaction—even if it means bending procedural norms. In this way, culture becomes a more flexible and responsive control mechanism than static rules (Hutcheson, 2025).

Levels of Organizational Culture

Organizational culture is a layered construct that encompasses both visible and invisible elements shaping how individuals perceive, behave, and interact within a workplace. Edgar Schein’s foundational model identifies three interrelated levels: artifacts, espoused values, and basic underlying assumptions (Schein, 2017). While this framework remains influential, contemporary organizational communication research has expanded its application, emphasizing psychological safety, inclusive rituals, and digital norms as deeper indicators of cultural health and adaptability (Edmondson & Bransby, 2023; Fernandez Cruz, 2025).

At the surface level, artifacts include observable symbols, language, dress codes, office layouts, and rituals. These tangible elements reflect the organization’s values and priorities. For example, Slack emojis, virtual coffee chats, and hybrid work policies now serve as cultural artifacts in remote-first organizations, signaling openness, flexibility, and informality (Khandelwal & Upadhyay, 2025). However, artifacts alone can be misleading if not aligned with deeper cultural layers.

The second level, espoused values, consists of explicitly stated principles and goals—often found in mission statements, DEI pledges, and leadership communications. Yet, critiques of this level highlight the frequent gap between stated values and enacted behaviors. For instance, a company may claim to value inclusion but fail to support diverse voices in decision-making or neglect inclusive onboarding rituals (Chronus, 2025). This disconnect underscores the importance of examining how values are operationalized through everyday communication and leadership practices.

At the deepest level lie basic underlying assumptions—unconscious beliefs about human nature, relationships, and organizational purpose. These assumptions are rarely articulated but profoundly shape behavior. Modern research suggests that psychological safety is a key indicator of these assumptions. When employees feel safe to speak up, take risks, and admit mistakes without fear of retribution, it reflects an underlying belief in trust, learning, and mutual respect (Edmondson & Bransby, 2023; Crossan, 2025). Inclusive rituals—such as celebrating diverse holidays, hosting feedback circles, or recognizing nontraditional career paths—also reveal assumptions about belonging, equity, and the value of difference (Reality Pathing, 2025).

Understanding organizational culture thus requires a multi-layered approach. Observing artifacts may offer initial clues, but deeper insights emerge through analyzing communication patterns, leadership behaviors, and the presence (or absence) of psychological safety and inclusive practices. As organizations navigate hybrid work, generative AI, and shifting employee expectations, these deeper cultural indicators are increasingly vital for resilience and innovation.

Insider Edge

Responding to a Toxic Workplace Culture

Objective

Equip employees with strategies to recognize and respond effectively when workplace culture deteriorates—when artifacts vanish, assumptions shift, behavioral norms collapse, and core values become distorted.

Why It Matters

Organizational culture is the invisible architecture of a workplace. When it turns toxic, it erodes trust, stifles innovation, and harms mental health. According to the APA’s 2024 Work in America survey, 15% of employees report working in toxic environments, with even higher rates among those with cognitive or emotional disabilities. Toxic cultures are linked to burnout, attrition, and ethical lapses that ripple across teams and industries.

Strategy Toolkit

| Action | How to Use It |

|---|---|

| Name the Shift | Use cultural language to describe what’s changed—e.g., “Our shared values feel diluted.” |

| Document Artifacts | Keep track of lost rituals, symbols, or practices that once reinforced positive culture. |

| Activate Voice Channels | Use anonymous surveys, suggestion boxes, or employee resource groups to speak up safely. |

| Seek Cultural Allies | Connect with colleagues who share your concerns and values to build collective resilience. |

| Engage in Upward Communication | Frame feedback constructively when speaking to leadership—focus on solutions, not blame. |

| Protect Your Compass | Reaffirm your own ethical standards and boundaries, even when norms around you shift. |

Empowerment Tip

“Culture is not just what leaders say—it’s what employees do, tolerate, and repeat.” If your workplace feels off, trust your instincts. You don’t have to fix everything alone, but you can start by refusing to normalize dysfunction.

References

Men, L. R., Yue, C. A., & McCornack, S. (2020). Strategic internal communication: Transformational leadership, communication channels, and employee voice. Public Relations Review, 46(2), 101880. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2020.101880

Sleek, S. (2024, June 27). Toxic workplaces leave employees sick, scared, and looking for an exit. American Psychological Association. Toxic workplace report

Morrison, E. W., & Milliken, F. J. (2000). Organizational silence: A barrier to change and development in a pluralistic world. Academy of Management Review, 25(4), 706–725. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2000.3707697

Discussion Questions

- Why is organizational culture considered a strategic asset in today’s workplace? Explore how culture impacts performance, adaptability, inclusion, and employee well-being, especially in hybrid and tech-enabled environments.

- Can you provide examples of cultural practices that serve as strengths and others that act as liabilities? Think about practices like flexible scheduling, inclusive onboarding, or overly rigid procedures—and how they shape employee engagement and innovation.

- How does culture operate as a behavioral compass beyond formal rules and policies? Discuss how underlying cultural norms guide actions when rules fall short, and how this can either support or hinder autonomy and responsiveness.

- If basic assumptions are unconscious and unspoken, what role do they play in shaping inclusive or exclusive environments? Reflect on how assumptions about human nature, trust, and belonging influence psychological safety, diversity efforts, and communication climates.

- What kinds of artifacts—both physical and digital—have you observed that signal a company’s underlying values and priorities? Consider things like remote collaboration tools, workspace design, wellness programs, emoji use, celebration rituals, and visible DEI commitments.

Section 15.3: Characteristics of Organizational Culture

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, you should be able to do the following:

- Identify and analyze key dimensions of organizational culture using the Organizational Culture Profile (OCP) framework and adaptive cultural attributes such as inclusivity, empathy, and resilience.

- Evaluate the concept of culture strength and its influence on organizational alignment, behavior, performance, and adaptability in changing environments.

- Examine the role of subcultures within organizations, including how they interact with dominant cultures and contribute to innovation, identity formation, and team effectiveness.

11 Dimensions of Culture

Organizational culture is shaped by a constellation of values that guide behavior, decision-making, and interpersonal dynamics. While culture may not be immediately observable, identifying core values allows leaders to assess and manage culture more effectively. One widely studied framework is the Organizational Culture Profile (OCP), which identifies seven key values: innovation, aggressiveness, outcome orientation, stability, people orientation, team orientation, and attention to detail (O’Reilly, Chatman, & Caldwell, 1991). However, contemporary organizational communication research highlights additional dimensions—such as empathy, resilience, and creativity—that are increasingly vital in adaptive and inclusive workplaces (Rae, 2024; Culture Amp, 2021).

Figure 15.4 Dimensions of Organizational Culture Profile (OCP)

Source: Adapted from information in O’Reilly, C. A., III, Chatman, J. A., & Caldwell, D. F. (1991). People and organizational culture: A profile comparison approach to assessing person-organization fit. Academy of Management Journal, 34, 487–516.

1. Innovative Cultures

Innovative cultures are characterized by flexibility, experimentation, and a tolerance for failure. These organizations often flatten hierarchies and empower employees to pursue novel ideas. For example, W. L. Gore & Associates fosters innovation through self-managed teams and a culture that celebrates both success and failure (Deutschman, 2004). Similarly, Google’s “20% time” policy has led to breakthrough products like Gmail and Google Maps (Morris, Burke, & Neering, 2006). During the COVID-19 pandemic, innovative cultures proved resilient by rapidly pivoting to remote work, launching new digital services, and reimagining customer engagement strategies (Brown et al., 2021).

2. Adaptive and Empathetic Cultures

Adaptive cultures prioritize learning, inclusivity, and emotional intelligence. These organizations respond to change with agility and compassion, recognizing that diverse perspectives fuel innovation and resilience (Patel, 2025). Empathy emerged as a strategic asset during the COVID-19 crisis, with leaders who practiced transparent communication and emotional support earning higher employee trust and engagement (Sull & Sull, 2020). For instance, HubSpot and Hilton were praised for empathetic leadership and inclusive practices that helped employees navigate uncertainty and maintain psychological safety.

3. Aggressive Cultures

Aggressive cultures emphasize competitiveness and market dominance. While this drive can lead to innovation and growth, it may also result in ethical lapses or neglect of social responsibility. Microsoft’s historical approach to competition—marked by combative rhetoric and legal disputes—illustrates the risks of unchecked aggressiveness (Greene, Reinhardt, & Lowry, 2004). Today, many organizations are rebalancing aggressive strategies with values like empathy and sustainability to align with stakeholder expectations.

Companies with aggressive cultures value competitiveness and outperforming competitors: By emphasizing this, they may fall short in the area of corporate social responsibility. For example, Microsoft Corporation is often identified as a company with an aggressive culture. The company has faced a number of antitrust lawsuits and disputes with competitors over the years. In aggressive companies, people may use language such as “We will kill our competition.” In the past, Microsoft executives often made statements such as “We are going to cut off Netscape’s air supply.…Everything they are selling, we are going to give away.” Its aggressive culture is cited as a reason for getting into new legal troubles before old ones are resolved (Greene, Reinhardt, & Lowry, 2004; Schlender, 1998). Recently, Microsoft founder Bill Gates established the Bill & Melinda Gates foundation and is planning to devote his time to reducing poverty around the world (Schlender, 2007). It will be interesting to see whether he will bring the same competitive approach to the world of philanthropy.

4. Outcome-Oriented Cultures

Outcome-oriented cultures focus on results, accountability, and performance metrics. Best Buy’s Results-Oriented Work Environment (ROWE) exemplifies this approach, allowing employees to work flexibly while being evaluated on clear objectives (Thompson, 2005). However, excessive emphasis on outcomes can foster unethical behavior, as seen in the collapse of Enron and WorldCom (Probst & Raisch, 2005). Adaptive cultures mitigate these risks by embedding values like creativity, collaboration, and ethical reflection into performance systems.

5. Intersectional and Inclusive Dimensions

Modern organizations increasingly recognize the importance of intersectionality—the overlapping social identities that shape employee experiences. Inclusive cultures go beyond demographic diversity to embrace rituals, communication norms, and leadership behaviors that support belonging and equity (Culture Amp, 2021; ADP, 2021). For example, during the pandemic, companies that acknowledged the unique challenges faced by caregivers, frontline workers, and marginalized groups were better able to retain talent and foster resilience (Rae, 2024).

6. Stable Cultures

Stable cultures prioritize predictability, rule adherence, and bureaucratic coordination. These organizations often thrive in environments that demand consistency and reliability, such as manufacturing or public sector institutions. However, in dynamic contexts, such rigidity may hinder innovation and responsiveness. Kraft Foods, for example, struggled with a culture-environment mismatch due to centralized decision-making and excessive bureaucracy (Thompson, 2006). Recent research suggests that stability can coexist with resilience when paired with open communication, psychological safety, and learning from failure (Smith, 2024).

7. People-Oriented Cultures

People-oriented cultures center on fairness, supportiveness, and respect for individual dignity. These organizations foster psychological safety, inclusive communication, and work-life integration. Starbucks exemplifies this approach through equitable compensation, benefits for part-time employees, and recognition rituals that reinforce belonging (Weber, 2005). During the pandemic, companies with strong people-oriented cultures were better equipped to support employee mental health and navigate uncertainty (Sull & Sull, 2020).

8. Team-Oriented Cultures

Team-oriented cultures emphasize collaboration, shared accountability, and collective problem-solving. Southwest Airlines cultivates this through cross-training, daily team huddles, and hiring practices that prioritize interpersonal fit (Miles & Mangold, 2005). In adaptive organizations, team culture becomes a microclimate for resilience and creativity, enabling rapid response to change and fostering inclusive decision-making (Campbell, 2025).

9. Detail-Oriented Cultures

Detail-oriented cultures value precision, consistency, and attentiveness—especially in customer-facing industries. Hospitality leaders like Four Seasons and Ritz-Carlton use data-driven personalization to enhance guest experiences, while McDonald’s operationalizes detail through standardized visual guides (Fitch, 2004). These cultures thrive when paired with empathy and proactive service, ensuring that attention to detail translates into meaningful customer care.

1-. Service Cultures

Service cultures prioritize customer satisfaction, empowerment, and proactive problem-solving. Organizations like Umpqua Bank and Nordstrom empower frontline employees to resolve issues creatively, often without managerial intervention (Conley, 2005). During COVID-19, service cultures that embraced empathy and flexibility—such as offering virtual consultations or community support—demonstrated resilience and deepened customer loyalty (Rey, 2022).

11. Safety Culture

Safety culture refers to the shared values, beliefs, and communication practices that prioritize physical and psychological well-being in the workplace. In safety-sensitive industries—such as aviation, construction, and energy—cultivating a robust safety culture is not only a moral imperative but also a strategic advantage. It reduces accidents, improves morale, enhances retention, and lowers operational costs (Altomonte, 2024).

The tragic 2005 explosion at British Petroleum’s Texas City refinery, which killed 15 workers and injured 170, underscored the consequences of neglecting safety culture. Investigations revealed systemic communication failures and a lack of leadership accountability. A safety review panel concluded that embedding safety into the organization’s culture—from executive decisions to frontline behaviors—was essential to prevent future disasters (Hofmann, 2007).

Modern safety cultures go beyond compliance. They foster emotional engagement, open dialogue, and psychological safety, where employees feel empowered to report hazards, share concerns, and suggest improvements without fear of retaliation (Campbell Institute, 2025). For example, M. B. Herzog Electric Inc. achieved a zero-accident rate over three years by tailoring safety training to specific roles and encouraging employees to act as OSHA inspectors for a day—an exercise that deepened awareness and ownership of safety practices.

Leadership plays a pivotal role in shaping safety culture. Managers who model safe behaviors and communicate consistently about safety expectations create environments where employees voluntarily participate in safety committees, intervene to protect coworkers, and engage in whistleblowing when necessary (Hofmann, Morgeson, & Gerras, 2003). Storytelling and personal testimonies—such as sharing lessons learned from near misses—also help internalize safety values and make them relatable (Campbell Institute, 2025).

During the COVID-19 pandemic, safety culture expanded to include mental health, remote work ergonomics, and inclusive communication. Organizations that prioritized empathy and transparency—such as offering anonymous reporting systems and non-punitive incident reviews—were better able to maintain trust and adapt to evolving risks (Sull & Sull, 2020).

Ultimately, safety culture is not a checklist—it’s a living system of communication, leadership, and shared responsibility. When embedded deeply, it transforms safety from a procedural obligation into a collective value.

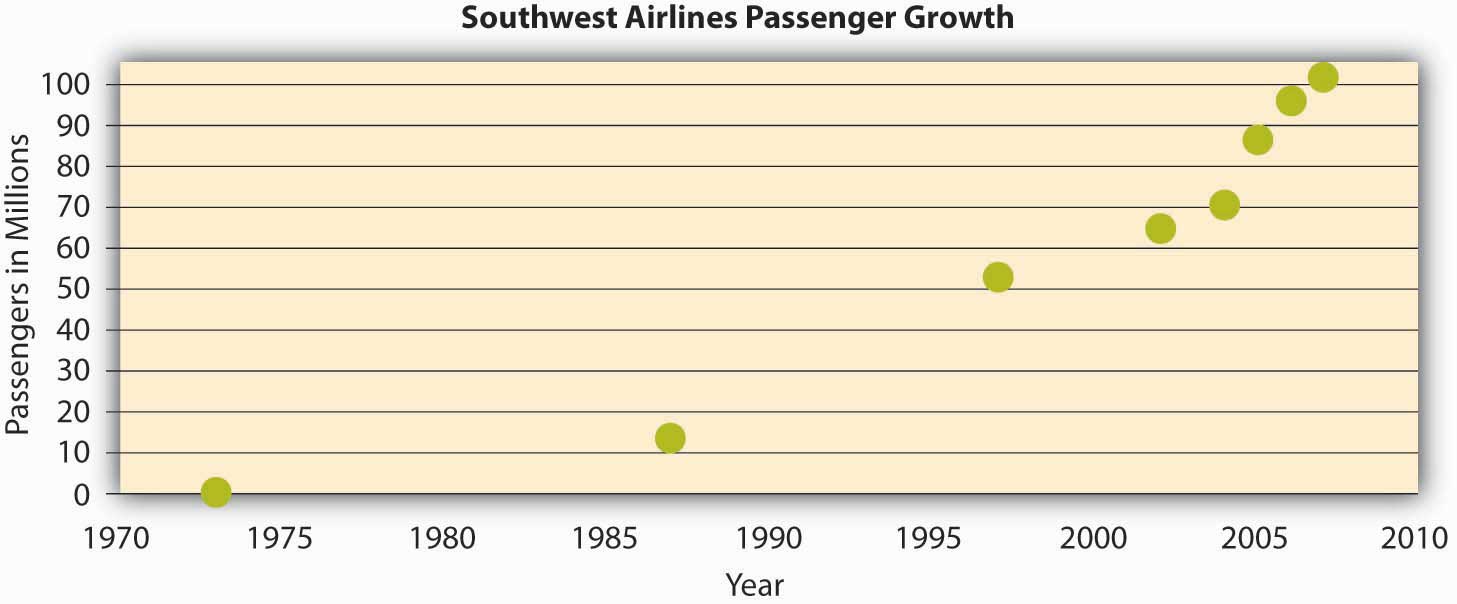

Figure 15.6

The growth in the number of passengers flying with Southwest Airlines from 1973 until 2007. In 2007, Southwest surpassed American Airlines as the most flown domestic airline. While price has played a role in this, their emphasis on service has been a key piece of their culture and competitive advantage.

Source: Adapted from http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/6/69/Southwest-airlines-passengers.jpg.

Strength of Culture

A strong organizational culture is defined by a high degree of consensus among members regarding shared values, norms, and behavioral expectations (Chatman & O’Reilly, 2016). When employees align around core cultural principles—such as customer service, innovation, or inclusion—those values become embedded in daily practices and decision-making. Strong cultures act as powerful behavioral compasses, shaping how individuals interpret their roles and interact with others (Lee, 2025).

However, strength alone does not guarantee effectiveness. A strong culture can be either an asset or a liability depending on its alignment with the external environment and ethical standards. For instance, a customer-centric culture like that of Zappos has been credited with driving loyalty and performance through shared service values (Hsieh, 2010). In contrast, Enron’s strong outcome-oriented culture, which emphasized aggressive performance metrics without ethical safeguards, contributed to its collapse (Probst & Raisch, 2005).

Strong cultures offer consistency and clarity, which can enhance performance in stable environments. Employees understand expectations, and communication flows more efficiently due to shared assumptions (Sorensen, 2002). Yet, in volatile or rapidly changing contexts, rigid cultural norms may hinder adaptability. Organizations with strong cultures may resist change, struggle to integrate new perspectives, or fail to respond to emerging challenges (Schein, 2017).

Cultural strength also complicates transformation efforts. When Robert Nardelli attempted to centralize decision-making at Home Depot—shifting from a decentralized, intuition-driven culture to a data-oriented model—he faced significant resistance. Despite financial gains, the cultural misalignment led to executive turnover and criticism of his leadership approach (Charan, 2006; Herman & Wernle, 2007).

Mergers and acquisitions further illustrate the risks of strong but incompatible cultures. The failed DaimlerChrysler merger revealed how deeply ingrained cultural differences—hierarchical engineering values versus autonomous sales norms—can obstruct integration and collaboration (Badrtalei & Bates, 2007). Modern research emphasizes the importance of cultural due diligence and communication alignment in merger contexts to avoid such pitfalls (Lee, 2025).

Ultimately, the strength of culture must be evaluated not only by its internal coherence but also by its adaptability, ethical grounding, and communicative openness. Organizations that cultivate strong cultures with built-in flexibility and psychological safety are better positioned to thrive amid complexity and change.

Do Organizations Have a Single Culture?

While organizational culture is often discussed as a unified system of shared values and norms, this view oversimplifies the complex reality of modern workplaces. In practice, organizations frequently host multiple subcultures—distinct cultural micro-communities that emerge within departments, teams, geographic locations, or generational cohorts (Boisnier & Chatman, 2002; Keswani, 2020). These subcultures reflect variations in work conditions, leadership styles, professional identities, and communication preferences. For example, the marketing team in a tech firm may prioritize creativity and agility, while the legal department may emphasize precision and risk aversion—both operating under the same corporate umbrella but with divergent cultural norms.

Subcultures are not inherently problematic. In fact, they can enhance organizational agility by allowing teams to adapt to specialized demands while still aligning with overarching values (Boisnier & Chatman, 2002). However, leaders must be attuned to how these subcultures influence employee engagement, collaboration, and commitment. Research shows that employees’ perceptions of their local subculture significantly affect their organizational loyalty and job satisfaction (Lok, Westwood, & Crawford, 2005). Understanding these dynamics is especially critical in hybrid and remote environments, where digital communication norms and team rituals can further differentiate subcultural identities (Aswani & Otiende, 2024).

Occasionally, subcultures evolve into countercultures—groups whose values and practices directly challenge the dominant organizational culture (Martin & Siehl, 1990). Countercultures often form around charismatic leaders or shared dissatisfaction with existing norms. For instance, a team of younger employees may reject hierarchical communication in favor of transparency and flat collaboration, especially if they feel excluded from decision-making. While countercultures can drive innovation and reform, they may also create friction, especially if perceived as undermining organizational cohesion (Keswani, 2020).

Managing subcultures and countercultures requires intentional communication, inclusive leadership, and cultural literacy. Leaders must balance the need for a coherent organizational identity with the flexibility to accommodate diverse values and practices. This includes fostering psychological safety, encouraging cross-functional dialogue, and recognizing the legitimacy of cultural variation as a source of strength rather than conflict.

Insider Edge

When Counterculture Meets Consequence

Objective

Empower employees to respond constructively and ethically when management punishes or marginalizes those who engage in workplace counterculture—such as challenging norms, advocating for change, or expressing dissent.

Why It Matters

Workplace counterculture can be a vital source of innovation, ethical accountability, and employee voice. However, when management suppresses it through punishment or exclusion, it fosters organizational silence, fear, and disengagement. Research shows that silencing dissent undermines psychological safety and stifles adaptive change (Morrison & Milliken, 2000). Employees need tools to navigate this tension without compromising their integrity or well-being.

Strategy Toolkit

| Action | How to Use It |

|---|---|

| Clarify Intentions | Frame your countercultural actions around shared values—e.g., fairness, inclusion, transparency. |

| Use Constructive Dissent | Express disagreement respectfully and with evidence. Avoid personal attacks or emotional escalation. |

| Leverage Safe Channels | Use formal feedback systems, ombuds services, or anonymous reporting tools to raise concerns. |

| Build Coalitions | Connect with others who share your perspective to amplify your voice and reduce isolation. |

| Document Interactions | Keep records of retaliatory behavior or disciplinary actions for future reference or escalation. |

| Know Your Rights | Review company policies and labor protections related to retaliation, whistleblowing, and free expression. |

Empowerment Tip

“Counterculture isn’t rebellion—it’s resilience.” When you challenge toxic norms, you’re not undermining the organization. You’re helping it evolve. Stay grounded in values, and don’t let fear silence your voice.

References

Morrison, E. W., & Milliken, F. J. (2000). Organizational silence: A barrier to change and development in a pluralistic world. Academy of Management Review, 25(4), 706–725. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2000.3707697

Men, L. R., Yue, C. A., & McCornack, S. (2020). Strategic internal communication: Transformational leadership, communication channels, and employee voice. Public Relations Review, 46(2), 101880. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2020.101880

Schein, E. H. (2010). Organizational culture and leadership (4th ed.). Jossey-Bass.

Discussion Questions

- Think about an organization you’re familiar with—how would you describe its culture using both the OCP framework and adaptive dimensions like empathy, resilience, or creativity? Consider how these values show up in communication practices, leadership behavior, or team rituals, especially in times of uncertainty or change.

- Which cultural dimensions do you believe are most associated with employee well-being and long-term retention? Which are most likely to drive organizational performance and innovation? Reflect on the balance between people-oriented, service-oriented, and outcome-oriented cultures.

- What are the benefits and risks of cultivating a strong outcome-oriented culture? How can organizations avoid ethical pitfalls and burnout while still maintaining accountability and performance benchmarks?

- How might different cultural values (e.g., stability, adaptability, inclusiveness) be more or less effective depending on the historical moment or industry context? Share your thoughts on why cultures that were once considered cutting-edge may now require transformation.

- Subcultures can be both beneficial and challenging—can you imagine or share an example where a subculture positively shaped a department, team, or remote office? What made it effective, and how was it managed in alignment with the broader organizational values?

Section 15.4: Creating and Maintaining Organizational Culture

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, you should be able to do the following:

- Explain how organizational cultures are created and co-constructed Understand the emergent and communicative processes through which culture is shaped, including how external challenges, leadership behaviors, employee interactions, and technology contribute to the formation of cultural norms and values.

- Analyze methods used to maintain and reinforce organizational culture Explore frameworks like attraction-selection-attrition (ASA), onboarding rituals, and symbolic practices—evaluating how tools, leadership, mentoring, and reward systems support cultural continuity across hybrid and remote settings.

- Identify and interpret the symbolic and visual elements of culture Recognize how mission statements, physical layouts, rituals, digital artifacts (e.g., Slack channels, emojis, onboarding videos), and storytelling practices serve as communicative cues that reflect and reinforce culture.

- Evaluate the role of leaders, employees, and digital technologies in shaping culture Examine how leadership communication, feedback loops, reverse mentoring, and AI-driven platforms facilitate inclusive, participatory, and adaptive culture-building.

- Reflect on personal culture fit and identity alignment in organizations Assess your own values, personality, and workplace preferences to better understand how culture influences individual experience and performance—and identify the cultural markers that foster belonging or misalignment.

Organizational culture is not a static blueprint handed down from leadership—it is an emergent, co-created system of shared meanings, shaped through communication, experience, and adaptation. While foundational models like Schein’s (2017) emphasize that culture forms as organizations respond to internal and external challenges, contemporary research reframes culture as a dynamic and participatory process. Culture is continuously constructed through everyday interactions, storytelling, rituals, and digital exchanges among organizational members (Levitt, 2010; Trice & Beyer, 1993).

In today’s hybrid and tech-enabled workplaces, AI tools and digital platforms play a transformative role in shaping culture. Technologies like Slack, Microsoft Teams, and generative AI assistants influence how norms are communicated, how inclusion is practiced, and how identity is expressed. For example, AI-powered feedback systems and sentiment analysis tools allow leaders to monitor cultural health in real time, uncovering patterns in employee engagement and psychological safety (Insight7, 2025). These tools democratize cultural insight, enabling organizations to respond proactively to emerging needs and values.

Moreover, inclusive and participatory culture-building practices are gaining prominence. Reverse mentoring programs—where junior employees mentor senior leaders on topics like digital fluency or DEI—challenge traditional hierarchies and foster mutual learning (Carter, 2023). Employee-led rituals, such as peer recognition ceremonies or storytelling circles, create shared meaning and reinforce belonging. Feedback loops, including pulse surveys and open forums, empower employees to shape cultural norms rather than passively absorb them (Workhuman, 2025).

Culture is also shaped by symbolic and communicative acts—from onboarding narratives to leadership language. As organizations navigate rapid change, those that embrace culture as a communicative process—where values are negotiated, not imposed—are more likely to foster resilience, innovation, and trust (Bantz, 1993; Sarangi, 2025). Leaders must recognize that culture is not just what is written in a handbook, but what is lived, shared, and reimagined through collective experience.

How Are Cultures Maintained?

Organizational culture is sustained through a complex interplay of communicative practices, structural mechanisms, and symbolic processes that reinforce shared values and norms over time. Contemporary organizational communication research emphasizes that culture is not merely preserved through static systems, but through ongoing interaction, storytelling, and alignment between individual identity and collective meaning (Brummans et al., 2014). As organizations mature, their cultural values become embedded in recruitment, onboarding, leadership behavior, and reward systems—each acting as a communicative channel through which culture is enacted and reinforced.

The Attraction-Selection-Attrition (ASA) model remains a foundational framework for understanding how organizations maintain cultural continuity. Schneider’s (1987) model posits that individuals are attracted to organizations whose values align with their own, organizations select candidates who fit their culture, and those who do not fit eventually leave. This cyclical process fosters cultural homogeneity. For example, tech companies like Apple and Microsoft have distinct cultures rooted in their founders’ values, which continue to shape hiring and retention practices decades later (iResearchNet, 2025). Modern applications of ASA include AI-driven personality assessments and culture-fit algorithms used in platforms like HireVue and Pymetrics, which streamline selection based on behavioral data.

Onboarding processes also play a critical role in cultural maintenance. Rather than simply orienting new hires to policies, effective onboarding immerses employees in the organization’s values, rituals, and communication norms. Companies like Facebook and HubSpot use immersive onboarding experiences that include storytelling sessions, peer mentoring, and digital culture guides to foster early alignment (SHRM, 2024). These practices help new employees internalize cultural expectations and contribute meaningfully from the outset.

Leadership and reward systems further reinforce culture by modeling desired behaviors and recognizing alignment. Leaders act as cultural communicators—through language, decision-making, and symbolic acts. For instance, Patagonia’s leadership emphasizes environmental stewardship not just in strategy but in everyday communication, reinforcing its activist culture. Reward systems, such as peer-nominated recognition programs or values-based bonuses, signal what behaviors are celebrated and thus perpetuate cultural norms (Workhuman, 2025).

Importantly, culture maintenance is reciprocal and emergent. Leaders shape culture, but culture also shapes leaders. Employees influence norms through feedback loops, social media discourse, and grassroots initiatives. Organizational communication scholars argue that culture is co-constructed through dialogue, not dictated from the top (Putnam & Nicotera, 2009). This view encourages organizations to treat culture as a living system—responsive to internal voices and external shifts.

New Employee Onboarding

Another way in which an organization’s values, norms, and behavioral patterns are transmitted to employees is through onboarding (also referred to as the organizational socialization process). Onboarding refers to the process through which new employees learn the attitudes, knowledge, skills, and behaviors required to function effectively within an organization. If an organization can successfully socialize new employees into becoming organizational insiders, new employees feel confident regarding their ability to perform, sense that they will feel accepted by their peers, and understand and share the assumptions, norms, and values that are part of the organization’s culture. This understanding and confidence in turn translate into more effective new employees who perform better and have higher job satisfaction, stronger organizational commitment, and longer tenure within the company (Bauer et al., 2007).

There are many factors that play a role in the successful adjustment of new employees. New employees can engage in several activities to help increase their own chances of success at a new organization. Organizations also engage in different activities, such as implementing orientation programs or matching new employees with mentors, which may facilitate onboarding.

What Can Employees Do During Onboarding?

Leadership plays a pivotal role in shaping organizational culture during onboarding by acting as communicators, role models, and architects of symbolic meaning. Contemporary organizational communication research emphasizes that leaders do not merely transmit culture—they co-create it through everyday interactions, storytelling, and strategic reinforcement (Brummans et al., 2014). Their influence is especially potent during onboarding, when new employees are most impressionable and actively constructing their understanding of the organization’s identity.

Role modeling is one of the most powerful tools leaders wield. When leaders consistently demonstrate behaviors aligned with organizational values—such as transparency, inclusivity, and ethical decision-making—they signal what is expected and acceptable. For example, leaders at Salesforce openly discuss company values during onboarding and model inclusive leadership by inviting feedback and sharing personal stories of growth (Chronus, 2025). This alignment between words and actions fosters trust and accelerates cultural assimilation.

Leader communication also shapes onboarding experiences. The questions leaders ask, the stories they tell, and the priorities they emphasize all contribute to the symbolic construction of culture. Leaders who ask about employee well-being, celebrate team wins, and acknowledge vulnerability help cultivate a supportive and people-oriented culture. Conversely, leaders who focus solely on metrics and competition may reinforce a performance-driven ethos (Sarros et al., 2002).

Reward systems, designed and enacted by leadership, further reinforce cultural norms. Modern research shows that total rewards strategies—encompassing compensation, recognition, and development opportunities—can be tailored to promote specific cultural attributes (Korn Ferry, 2024). For instance, organizations that reward collaboration and innovation through team bonuses and peer recognition programs tend to foster inclusive and creative cultures. In contrast, companies that rank employees and reward only top performers may cultivate competitive environments that discourage psychological safety.

Moreover, leaders’ reactions to employee behavior during onboarding send powerful cultural signals. Whether they respond to mistakes with curiosity or criticism, whether they reward effort or only outcomes—these choices shape the emerging norms. Leaders at companies like Patagonia and HubSpot are known for celebrating values-aligned behaviors, such as environmental stewardship or radical transparency, even when those actions don’t immediately yield results (Workhuman, 2025).

Ultimately, onboarding is a communicative process, and leaders are its chief narrators. Their actions, language, and reward systems collectively shape how new employees interpret and internalize the organization’s culture.

Workplace Strategy Pack

Successful Onboarding in a New Workplace

Objective

Help employees navigate the onboarding process with confidence, clarity, and connection—so they can integrate into the organizational culture, build relationships, and contribute meaningfully from day one.

Why It Matters

Effective onboarding is more than orientation—it’s a strategic communication process that shapes employee identity, engagement, and retention. Research shows that structured onboarding improves job satisfaction, performance, and organizational commitment (Bauer, 2010). When employees understand cultural norms, communication channels, and role expectations early, they’re more likely to thrive and stay.

Strategy Toolkit

| Action | How to Use It |

|---|---|

| Decode the Culture | Observe rituals, language, and informal norms. Ask colleagues about “how things get done.” |

| Clarify Expectations | Request feedback early and often. Confirm role responsibilities and success metrics. |

| Build Communication Bridges | Learn preferred channels (email, chat, meetings) and adapt to team communication styles. |

| Engage in Dialogue | Ask questions that show curiosity and initiative. Use active listening to build trust. |

| Find Cultural Mentors | Identify colleagues who model the organization’s values and can guide your integration. |

| Track Your Journey | Keep a journal of wins, challenges, and questions to reflect on your growth and progress. |

Empowerment Tip

“You’re not just joining a company—you’re shaping its culture.” Your fresh perspective is valuable. Don’t be afraid to ask why things are done a certain way. Sometimes, the best ideas come from the newest voices.

References

Bauer, T. N. (2010). Onboarding new employees: Maximizing success. SHRM Foundation. https://www.shrm.org/foundation/products/pages/onboardingepg.aspx

Jablin, F. M. (2001). Organizational entry, assimilation, and disengagement/exit. In F. M. Jablin & L. L. Putnam (Eds.), The new handbook of organizational communication: Advances in theory, research, and methods (pp. 732–818). Sage Publications.

Kramer, M. W. (2010). Organizing words: The meanings of communication in organizations. Oxford University Press.

Workplace Strategy Pack

Maximizing Onboarding Success

Objective

Provide employees with actionable best practices to navigate onboarding effectively—ensuring they integrate into the organization, build relationships, and contribute meaningfully from the start.

Why It Matters

Onboarding is a critical phase that shapes employee engagement, retention, and performance. A well-executed onboarding process helps new hires internalize organizational culture, understand expectations, and feel psychologically safe. Research shows that structured onboarding leads to higher job satisfaction, faster productivity, and stronger organizational commitment (Bauer, 2010). When onboarding is neglected or inconsistent, employees may feel disconnected, confused, or undervalued.

Strategy Toolkit

| Best Practice | How to Use It |

|---|---|

| Preboard with Purpose | Engage before day one—send welcome messages, schedules, and cultural insights to build excitement. |

| Clarify Role Expectations | Ask for a clear outline of responsibilities, success metrics, and reporting structures. |

| Observe and Decode Culture | Pay attention to rituals, communication styles, and informal norms. Ask questions to understand unwritten rules. |

| Build a Relationship Map | Identify key stakeholders, mentors, and collaborators. Schedule brief intro meetings to build rapport. |

| Use Active Listening | Listen for tone, values, and priorities in meetings and conversations. Reflect back to show understanding. |

| Track Your Progress | Keep a journal or checklist of onboarding milestones, questions, and accomplishments. |

| Ask for Feedback Early | Request input on your performance and integration within the first few weeks to course-correct if needed. |

Empowerment Tip

“Onboarding isn’t just about fitting in—it’s about finding your place and adding value.” Your fresh perspective is a strength. Use it to ask thoughtful questions, challenge assumptions, and contribute with confidence.

References

Bauer, T. N. (2010). Onboarding new employees: Maximizing success. SHRM Foundation. https://www.shrm.org/foundation/products/pages/onboardingepg.aspx

Klein, H. J., & Heuser, A. E. (2008). The learning and performance effects of self-directed versus other-directed onboarding. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 23(4), 386–405. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683940810869021

Jablin, F. M. (2001). Organizational entry, assimilation, and disengagement/exit. In F. M. Jablin & L. L. Putnam (Eds.), The new handbook of organizational communication: Advances in theory, research, and methods (pp. 732–818). Sage Publications.

Visual Elements of Organizational Culture

Organizational culture is not only communicated through values and behaviors—it is also visually and symbolically expressed through tangible and digital artifacts that shape how employees experience and interpret their workplace. In remote and hybrid environments, these visual elements become even more critical, as they serve as anchors for identity, belonging, and shared meaning across dispersed teams (Brummans et al., 2014).

Mission statements act as cultural compasses, articulating purpose and guiding behavior. In hybrid settings, companies like GitLab and HubSpot ensure their mission statements are not just posted on websites but embedded into onboarding materials, Slack channels, and leadership communications (Murph, 2023). These statements are reinforced through storytelling and recognition programs that tie employee actions to core values.

Rituals, both formal and informal, foster connection and continuity. Remote-first companies like Zapier and Buffer host weekly “Friday Wins” Slack threads, virtual coffee chats, and asynchronous shoutouts using emojis and gifs to celebrate milestones and reinforce values (CultureBot, 2025). These rituals create rhythm and emotional resonance, replacing the ambient cues of physical offices.

Rules and policies also shape culture visually and symbolically. For example, remote work policies that prioritize flexibility and trust signal autonomy and inclusion. GitLab’s publicly documented handbook outlines expectations for communication, feedback, and collaboration, serving as a living cultural artifact accessible to all employees (GitLab, 2025).

Physical layout, though less central in remote work, still influences hybrid culture. Offices are increasingly designed as collaboration hubs rather than daily workspaces, with open lounges, flexible meeting rooms, and branded decor that reflect company values (Morris, 2025). These spaces are used intentionally for rituals like team summits or onboarding days, reinforcing cultural identity.

Stories—whether shared in onboarding, newsletters, or team meetings—are powerful tools for transmitting culture. Companies like Patagonia and Airbnb use origin stories and employee narratives to reinforce values like sustainability and belonging. These stories are often shared through digital media, making them accessible across locations and time zones.

Digital artifacts are the new cultural scaffolding in remote and hybrid work. Slack channels dedicated to gratitude, emojis used to signal team norms (e.g., 👏 for recognition, 🔥 for urgency), and onboarding videos that introduce cultural rituals all serve as visual cues that shape behavior and identity (Carter, 2020). Platforms like Notion and Miro are used to co-create culture documents, team charters, and visual workflows that reflect shared values and practices.

Together, these visual elements form a symbolic ecosystem that communicates what the organization stands for, how it operates, and how employees can belong and contribute—regardless of where they work.

Conclusion

Visual elements in organizational culture serve as powerful communicative anchors, especially in remote and hybrid environments where traditional face-to-face interactions are limited. Together, mission statements, rituals, rules and policies, physical layouts, stories, and digital artifacts create an interconnected cultural mosaic that guides behavior, fosters identity, and cultivates community. These tangible and symbolic cues not only make abstract values visible—they also democratize culture-building by inviting employees to contribute, interpret, and live the culture in personally meaningful ways.

In increasingly distributed workplaces, the most resilient cultures are those built intentionally through both communication and design. Leaders and teams who embrace visual symbols as vessels of meaning can co-create vibrant, inclusive, and adaptive cultures that transcend geography and technology.

Workplace Strategy Pack

Assessing Organizational Fit During the Interview Process

Objective

Equip job candidates with strategies to evaluate whether their values, work style, and career goals align with the culture, expectations, and mission of the organization they’re interviewing with.

Why It Matters

Organizational fit is a key predictor of job satisfaction, performance, and retention. Candidates who align with a company’s culture are more likely to thrive, while poor fit can lead to disengagement and early turnover. Research shows that cultural congruence enhances communication, collaboration, and psychological safety (Chatman & O’Reilly, 2016). Interviews are not just about impressing the employer—they’re also a chance to assess whether the organization is right for you.

Strategy Toolkit

| Best Practice | How to Use It |

|---|---|

| Ask Culture-Driven Questions | Inquire about values, leadership style, decision-making norms, and team dynamics. Example: “How does the team handle conflict or feedback?” |

| Observe Communication Style | Pay attention to tone, responsiveness, and transparency during the interview process. |

| Request Stories, Not Just Stats | Ask interviewers to share examples of how the company lives its values. Stories reveal more than slogans. |

| Research Public Signals | Review Glassdoor, LinkedIn, and press releases for patterns in employee sentiment and organizational behavior. |

| Reflect on Emotional Cues | After each interaction, ask yourself: “Did I feel energized, respected, and heard?” |

| Compare to Your Personal Compass | List your top values and career goals. See how they align with what you’ve learned about the company. |

Empowerment Tip

“You’re not just applying for a job—you’re choosing a culture.” Treat the interview as a two-way dialogue. You deserve to work in a place that supports your growth, values your voice, and aligns with your purpose.

References

Chatman, J. A., & O’Reilly, C. A. (2016). Paradigm lost: Reinvigorating the study of organizational culture. Research in Organizational Behavior, 36, 199–224. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.riob.2016.11.004

Cable, D. M., & Judge, T. A. (1996). Person–organization fit, job choice decisions, and organizational entry. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 67(3), 294–311. https://doi.org/10.1006/obhd.1996.0081

Kramer, M. W. (2010). Organizing words: The meanings of communication in organizations. Oxford University Press.

Insider Edge

When Your Manager Undermines Foundational Values

Objective

Equip employees with strategies to respond constructively when their manager’s actions or attitudes conflict with the organization’s founding values, industry expectations, and cultural legacy.

Why It Matters

Founders’ values often serve as the cultural DNA of an organization—shaping its identity, guiding decisions, and anchoring employee behavior. When a manager disregards these values, it can create cultural dissonance, erode trust, and destabilize team alignment. Research shows that misalignment between leadership behavior and organizational values leads to employee disengagement, ethical confusion, and communication breakdowns (Schein, 2010; Kramer, 2010).

Strategy Toolkit

| Action | How to Use It |

|---|---|

| Clarify the Disconnect | Identify specific ways your manager’s behavior diverges from the organization’s stated values or goals. |

| Reaffirm Cultural Anchors | Use company documents, founder statements, or mission language to reinforce shared values in team discussions. |

| Engage in Upward Communication | Frame feedback constructively—focus on alignment, not accusation. Use “I” statements and cite organizational goals. |

| Seek Cultural Mentors | Connect with long-tenured employees or cross-functional leaders who embody the founders’ vision. |

| Document and Reflect | Keep a record of decisions or behaviors that conflict with cultural expectations. Use this for future reference or escalation. |

| Explore Internal Mobility | If misalignment persists, consider transferring to a team or leader more aligned with your values. |

Empowerment Tip

“Culture isn’t just inherited—it’s protected.” You have the power to uphold the values that made your organization meaningful. Even when leadership falters, your voice can help restore clarity and purpose.

References

Schein, E. H. (2010). Organizational culture and leadership (4th ed.). Jossey-Bass.

Kramer, M. W. (2010). Organizing words: The meanings of communication in organizations. Oxford University Press.

Men, L. R., Yue, C. A., & McCornack, S. (2020). Strategic internal communication: Transformational leadership, communication channels, and employee voice. Public Relations Review, 46(2), 101880. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2020.101880

Discussion Questions

- In today’s digitally mediated and inclusive workplace cultures, how should organizations balance hiring for person-organization fit with the need to foster diversity of thought and experience? What are the cultural risks and benefits of hiring based primarily on alignment with company values and behaviors?

- Founders often set the tone for organizational culture through their vision, values, and leadership style. How do these founding narratives continue to influence cultural rituals, symbols, and norms in mature organizations? Can you name companies where founder influence still strongly guides culture (e.g., Patagonia, Apple, Salesforce)?

- Based on your understanding of onboarding as both a procedural and symbolic process, what methods—from mentorship programs to Slack rituals—do organizations use to immerse employees in culture? Why is onboarding increasingly seen as a strategic and communicative touchpoint, especially in remote and hybrid settings?

- Reflecting on your own personality, work preferences, and values, what kind of organizational culture do you believe would allow you to thrive? Conversely, what cultural environments might create dissonance for you? Have you ever experienced cultural misalignment in a workplace, and how did it affect your engagement or performance?

- How do visual and symbolic elements—such as office layout, digital channels like Slack, use of emojis, or virtual onboarding rituals—serve to reinforce culture in hybrid and remote organizations? What kinds of physical or digital environments would you expect in cultures that are collaborative, competitive, or stability-focused?

Section 15.5: Creating Culture Change

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, you should be able to do the following:

- Describe the conditions and challenges that make culture change necessary in dynamic organizational environments.

- Analyze the process of culture transformation through movement-based approaches.

- Evaluate the role of organizational communication in building momentum for culture change.

- Apply strategies for initiating and sustaining culture change within diverse organizational settings.

Culture change is no longer a top-down mandate—it’s a movement. While traditional models like Schein’s (2017) six-step framework remain foundational, current organizational communication research emphasizes that lasting cultural transformation emerges through distributed leadership, storytelling, and participatory rituals that engage employees at every level (Korn Ferry, 2024; BTS, 2024).

Organizations often recognize the need for culture change when facing environmental misalignment, declining performance, or post-merger integration challenges. However, urgency alone is insufficient. Today’s successful change efforts rely on movement-making—a collective, emotionally resonant process that connects employees to a shared purpose and empowers them to co-create the future (BTS, 2024). For example, when IBM faced existential threats in the 1990s, CEO Lou Gerstner used the crisis not just to mandate change but to galvanize employees around a new cultural narrative (Gerstner, 2002).

1. Distributed Leadership

Distributed leadership is central to this approach. Rather than relying solely on executive vision, organizations now cultivate “change agents” across departments—individuals who model new behaviors, spark dialogue, and build momentum through peer influence (Korn Ferry, 2024). These leaders often emerge organically and are supported through storytelling platforms, recognition rituals, and feedback loops.

2. Storytelling

Storytelling plays a transformative role in shaping and sustaining cultural movements. Leaders and employees share personal narratives that reflect desired values, making abstract concepts tangible and emotionally compelling (Alfaro, 2023). For instance, organizations like Patagonia and Airbnb use origin stories and employee testimonials to reinforce values like sustainability and belonging. These stories are circulated through digital channels, onboarding videos, and internal newsletters, creating a shared cultural lexicon.

3. Rituals and Symbols

Rituals and symbols also evolve to reflect new cultural priorities. In hybrid and remote environments, digital artifacts—such as Slack emojis, virtual celebrations, and collaborative Notion pages—serve as visual cues that reinforce norms and foster connection (CultureBot, 2025). These rituals are not imposed but co-created, allowing employees to shape culture through everyday interactions.

4. Training and Reward Systems

Training and reward systems remain important but are now designed to support movement-based change. Programs focus on emotional intelligence, inclusive leadership, and psychological safety—equipping employees to navigate ambiguity and contribute meaningfully. Recognition systems highlight values-aligned behaviors, not just outcomes, reinforcing the cultural shift (Workhuman, 2025).

Ultimately, culture change is not a linear checklist—it’s a dynamic, communicative process that requires empathy, authenticity, and shared ownership. Organizations that embrace storytelling, distributed leadership, and inclusive rituals are better positioned to build resilient, adaptive cultures that thrive in complexity.

Insider Edge

Responding to a Declining Workplace Culture

Objective

To empower employees with strategies to recognize and respond constructively when organizational culture begins to deteriorate—when values erode, norms shift, and the behavioral compass loses direction.

Why It Matters

Organizational culture is shaped by shared values, visible artifacts, and underlying assumptions. When these elements begin to unravel—due to leadership changes, external pressures, or internal neglect—employees may experience confusion, disengagement, and ethical tension. Research shows that communication plays a critical role in shaping and sustaining culture, and that silence or misalignment can accelerate cultural decline (Schein, 2010; Barbaros, 2020).

Employees are not passive observers—they are cultural contributors. Recognizing and responding to negative shifts is essential to preserving integrity and psychological safety.

Strategy Toolkit

| Action | How to Use It |

|---|---|

| Name the Change | Use cultural language to describe what’s shifting—e.g., “We’ve lost the rituals that used to connect us.” |

| Reaffirm Core Values | Reference mission statements, founder principles, or legacy practices to anchor conversations. |

| Initiate Dialogue | Use team meetings or one-on-ones to ask: “What’s changed in how we work together?” |

| Document Cultural Signals | Track changes in communication tone, decision-making, and recognition practices. |

| Build Microcultures of Integrity | Create pockets of positivity and ethical behavior within your team or peer group. |

| Engage Leadership Thoughtfully | Frame feedback around shared goals and organizational success—not personal critique. |

Empowerment Tip

“Culture doesn’t collapse overnight—it erodes in silence.” If you see something shifting, say something. Your voice can help restore clarity, connection, and purpose.

References

Schein, E. H. (2010). Organizational culture and leadership (4th ed.). Jossey-Bass.

Barbaros, S. (2020). The intersection of organizational culture and communication: Shaping workplace success. Academy of Strategic Management Journal, 19(6), 1–10. https://www.abacademies.org/articles/the-intersection-of-organizational-culture-and-communication-shaping-workplace-success.pdf

Cameron, K. S., & Quinn, R. E. (2011). Diagnosing and changing organizational culture (3rd ed.). Jossey-Bass.

Discussion Questions

- In what ways can new employees contribute to a culture change movement within an organization? Consider how storytelling, peer influence, and shared rituals might empower newcomers to act as change agents rather than passive observers.

- What organizational or environmental conditions might limit the possibility of culture change? Reflect on factors such as lack of psychological safety, rigid hierarchies, or absence of shared purpose that could hinder collective transformation.

- Have you ever experienced or witnessed a culture change effort in an organization? What elements of movement-based change—such as distributed leadership, symbolic actions, or participatory rituals—were present, and what impact did they have?

- What strategies would you recommend to someone initiating a major culture shift in their organization today? Include insights on building emotional resonance, empowering distributed leaders, and creating inclusive symbols or stories to sustain momentum.

Section 15.6: Ethical and Cultural Influences

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, you should be able to do the following:

- Analyze how organizational culture influences ethical behavior and the perception of ethical norms. Explore how factors such as psychological safety, ethical climate, leadership, and communication shape the moral compass within an organization.

- Evaluate the impact of national cultural dimensions on organizational practices and cultural adaptation. Consider models like Hofstede and GLOBE to identify how values such as power distance, collectivism, and uncertainty avoidance can affect leadership styles, employee interactions, and ethical expectations across cultures.

Organizational culture and ethics are deeply intertwined, and recent research emphasizes that ethical behavior is not simply a matter of individual choice—it’s shaped by the communicative environment, leadership practices, and cultural context in which employees operate. Creating an ethical culture requires more than compliance programs; it demands intentional leadership, psychological safety, and sensitivity to global cultural dynamics.

Global and Cross-Cultural Perspectives

Multinational organizations must navigate the complex interplay between national culture and organizational ethics. Hofstede’s cultural dimensions—such as power distance, individualism vs. collectivism, and uncertainty avoidance—offer a foundational framework for understanding how cultural values influence workplace behavior (Hofstede, 2011). However, critics argue that Hofstede’s model oversimplifies cultural complexity and lacks adaptability to modern, dynamic organizational contexts (Ghemawat & Reiche, 2011). The GLOBE study expands on Hofstede’s work by introducing dimensions like performance orientation and humane orientation, which are particularly relevant to ethical leadership and organizational behavior (House et al., 2004).

For example, in high power distance cultures such as South Korea, deference to authority may inhibit whistleblowing or ethical dissent, while in low power distance cultures like Sweden, open dialogue and participatory decision-making are more common. These cultural norms directly affect how ethical standards are communicated and upheld. Multinational firms must therefore tailor their ethics programs to local contexts while maintaining global consistency. Failure to do so can result in ethical misalignment, as seen in cases where Western firms impose transparency norms in collectivist cultures that prioritize relational harmony over confrontation (Minbaeva et al., 2018).

Ethical Culture and Psychological Safety

Ethical culture is also a key predictor of employee well-being, engagement, and burnout prevention. Kaptein’s Corporate Ethical Virtues Model (CEVM) identifies eight dimensions—clarity, congruency, feasibility, supportability, transparency, discussability, and sanctionability—that collectively foster an ethical climate (Kaptein, 2008). Organizations that score high on these virtues tend to have lower rates of misconduct and higher levels of trust and psychological safety.

Psychological safety, defined as the belief that one can speak up without fear of punishment or humiliation, is essential for ethical dialogue and innovation (Edmondson, 2019). When employees feel safe to raise concerns, challenge unethical practices, or admit mistakes, organizations become more resilient and adaptive. Ethical leadership plays a pivotal role here: leaders who model integrity and openness create environments where ethical behavior is not only expected but supported.

Moreover, ethical culture correlates positively with leadership well-being. Leaders in ethically aligned organizations report lower stress and higher job satisfaction, as they are not forced to compromise values for performance (Huhtala et al., 2011). This alignment also boosts employee engagement, as workers are more likely to feel connected to a purpose-driven organization that values fairness and transparency.

In sum, cultivating an ethical organizational culture requires a nuanced understanding of global cultural dynamics, intentional leadership, and systems that promote psychological safety. Ethics is not a static code—it’s a living, communicative practice embedded in the everyday rituals, stories, and relationships of the workplace.

Insider Edge

What to Do When Psychological Safety Is Ignored

Objective

To equip employees with strategies to recognize, respond to, and protect themselves when their organization’s culture intentionally neglects psychological safety—where fear, silence, and retaliation replace openness, trust, and inclusion.

Why It Matters

Psychological safety is the belief that one can speak up, take risks, and express concerns without fear of punishment or humiliation (Edmondson, 1999). When organizations intentionally devalue this principle, employees may experience chronic stress, disengagement, and ethical dilemmas. Communication breakdowns become normalized, and innovation suffers.

Organizational communication research shows that cultures lacking psychological safety often rely on top-down messaging, suppress dissent, and discourage feedback loops (Tourish, 2020). Employees must learn to navigate these environments without compromising their integrity or well-being.

Strategy Toolkit

| Action | How to Use It |

|---|---|

| Recognize the Signals | Watch for retaliation, exclusion, or punishment for speaking up. Silence is often strategic. |

| Protect Your Voice | Use neutral, fact-based language when raising concerns. Avoid emotional framing in unsafe cultures. |

| Build Peer Alliances | Create informal support networks with trusted colleagues to share experiences and validate concerns. |

| Document Interactions | Keep records of problematic communications or decisions. This protects your credibility. |

| Use External Channels Wisely | If internal options are compromised, consider HR, ombuds services, or whistleblower protections. |

| Practice Boundary Setting | Know when to disengage from toxic dynamics. Your psychological health is non-negotiable. |

Empowerment Tip

“Silence may feel safe—but it’s not always wise.” Your voice matters. Even in unsafe cultures, strategic communication can protect your values and influence change over time.

References

Edmondson, A. C. (1999). Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44(2), 350–383. https://doi.org/10.2307/2666999

Tourish, D. (2020). The triumph of silence: Exploring the dark side of leadership and organizational communication. Oxford University Press.

Schein, E. H. (2010). Organizational culture and leadership (4th ed.). Jossey-Bass.

Discussion Questions

- Can you share a real-world example where an organization’s culture reinforced ethical or unethical behavior? Reflect on how leadership actions, reward systems, or communication norms contributed to the outcome. Did employees feel safe raising concerns? Was ethical behavior actively supported or subtly discouraged?