Chapter 2: Managing Demographic and Cultural Diversity

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, you should be able to do the following:

- Understand what constitutes diversity.

- Explain the benefits of managing diversity.

- Describe challenges of managing a workforce with diverse demographics.

- Describe the challenges of managing a multicultural workforce.

- Understand diversity and ethics.

- Understand cross-cultural issues regarding diversity.

Around the world, the workforce is becoming diverse. In 2022, women constituted 56.8% of the workforce in the United States. In the same year, 53.5% of the workforce was African American, 51.3% were of Hispanic origin, and 52.1% were Asian (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2023). Employees continue to work beyond retirement, introducing age diversity to the workforce. Regardless of your gender, race, and age, it seems that you will need to work with, communicate with, and understand people different from you at school as well as at work. Understanding cultures different from your own is also becoming increasingly important due to the globalization of business. In the United States, 53.4% of domestic female employees were foreign born, indicating that even those of us who are not directly involved in international business may benefit from developing an appreciation for the differences and similarities between cultures (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2023). In this chapter, we will examine particular benefits and challenges of managing a diverse workforce and discuss ways in which you can increase your effectiveness when working with diversity.

As we discuss differing environments faced by employees with different demographic traits, we primarily concentrate on the legal environment in the United States. Please note that the way in which demographic diversity is treated legally and socially varies around the globe. For example, countries such as Canada and the United Kingdom have their own versions of equal employment legislation. Moreover, how women, employees of different races, older employees, employees with disabilities, and employees of different religions are viewed and treated shows much variation based on the societal context.

Section 2.1: Spotlight

Section 2.1

Creating Cultures of Excellence: Why These St. Louis Companies Are Among the Best Places to Work

In today’s dynamic job market, workplace culture has emerged as a defining feature of successful organizations. The St. Louis Business Journal’s 2025 “Best Places to Work” list celebrates companies that foster vibrant, inclusive, and innovative work environments. This essay explores the workplace cultures of four notable honorees—Lochmueller Group, Capes Sokol, ITF Group, and Enterprise Bank & Trust—highlighting what makes each company exceptional, their commitments to diversity, and how their innovative approaches shape both employee satisfaction and business success.

Lochmueller Group, a planning and engineering consultancy, stands out for its people-first philosophy rooted in employee ownership. As an Employee Stock Ownership Plan (ESOP) company, Lochmueller empowers its team by sharing equity, creating a sense of mutual accountability and shared mission (Lochmueller Group, 2025). This model promotes intrinsic motivation and engagement, as employees literally invest in each other’s success.

Their workplace culture thrives on transparency, mentorship, and continuous learning. Flexibility is also a core value, allowing employees to balance personal goals with professional growth. The firm’s recognition as a top workplace is a testament to how structural inclusivity and open communication can create a sustainable, motivating environment.

Capes Sokol, a mid-sized law firm in St. Louis, demonstrates that excellence in legal practice begins with an empathetic, collaborative culture. The firm focuses on genuine communication and listening, empowering attorneys and staff to contribute meaningfully to the firm’s vision. As a result, Capes Sokol has been honored for its egalitarian structure and the way it values both professional and personal development (St. Louis Business Journal, 2025a).

Culturally, Capes Sokol has cultivated a space that embraces diversity—not just demographically, but ideologically. The firm has implemented mentorship and internship programs that offer access and visibility to individuals from underrepresented backgrounds in the legal field.

ITF Group, a logistics and freight company, clinched first place in the medium-sized company category in 2025. Their ascent is largely due to a culture of innovation, cross-departmental collaboration, and strong leadership. ITF Group actively nurtures employee engagement through programs that reward creative problem-solving and peer-to-peer recognition (ITF Group, 2025).

Diversity plays a strategic role in their success. The company embraces inclusive hiring practices and makes a conscious effort to reflect the cultural richness of the communities it serves. Training programs focused on leadership development and communication across cultures indicate a long-term investment in a global perspective.

Consistently ranked among St. Louis’ top employers, Enterprise Bank & Trust’s secret lies in its balanced approach to employee development and community enrichment. Their workplace culture hinges on the belief that thriving communities build thriving businesses. To that end, they offer Enterprise University, a free program that supports both employees and clients with professional education (Enterprise Bank & Trust, 2025).

Their commitment to diversity includes employee resource groups, inclusive hiring initiatives, and leadership development tracks that highlight equity and belonging. By offering paid volunteer time and encouraging philanthropic participation, the bank reinforces its values of service and shared success.

Each of these organizations recognizes that a positive workplace culture is not a luxury—it is a strategic asset. According to Deloitte’s 2023 Human Capital Trends report, companies with inclusive, innovative cultures are more likely to outperform their competitors financially and attract top talent (Deloitte, 2023).

Moreover, these St. Louis companies understand that diversity is not only a matter of fairness but a wellspring of creativity and resilience. By hiring and training diverse teams, they bring multiple perspectives into decision-making, allowing for nuanced problem-solving and greater adaptability.

Innovation, meanwhile, is built into the DNA of each company. Whether it’s Lochmueller’s agile planning tools, ITF Group’s logistics technologies, or Enterprise Bank’s professional development platforms, the shared theme is clear: innovating with purpose enhances both employee experience and service delivery.

In a region rich with talent and tradition, companies like Lochmueller Group, Capes Sokol, ITF Group, and Enterprise Bank & Trust are redefining what it means to be a great place to work. Through strong cultural values, commitments to diversity, and relentless innovation, they’ve built workplaces that don’t just function—they flourish.

References

Deloitte. (2023). 2023 Global Human Capital Trends: New Fundamentals for a Boundaryless World. https://www2.deloitte.com/global/en/pages/human-capital/articles/introduction-human-capital-trends.html

Enterprise Bank & Trust. (2025). Why We’re a Best Place to Work. https://www.enterprisebank.com/

ITF Group. (2025). About Us. https://www.itfgroup.com/

Lochmueller Group. (2025). Careers at Lochmueller. https://www.lochgroup.com/

St. Louis Business Journal. (2025a). Best Places to Work 2025: Capes Sokol. https://www.bizjournals.com/stlouis/

St. Louis Business Journal. (2025b). Best Places to Work 2025: ITF Group, Lochmueller, Enterprise Bank. https://www.bizjournals.com/stlouis/

Discussion Questions

- What are these organization’s competitive advantages?

- What problems might result from hiring and training the diverse populations that these organizations are involved with?

- Have you ever experienced problems with discrimination in a work or school setting?

- Why do you think that these organizations believe it necessary to continually innovate?

Section 2.2 Demographic Diversity

Learning Objectives

After completing this chapter, you should be able to:

- Analyze the organizational benefits of effectively managing diversity, including improved innovation, employee engagement, and market responsiveness.

- Evaluate the challenges associated with diversity management, such as unconscious bias, communication barriers, and resistance to change, and propose strategies to address them.

- Describe and compare the workplace experiences of employees with diverse identities—including gender, race, religion, physical ability, age, and sexual orientation—within varying organizational climates.

- Apply inclusive communication and leadership strategies to support equity and belonging across diverse teams.

- Create a personal or team action plan for fostering inclusive practices in a professional or academic setting.

Section 2.2

Understanding Diversity and Its Role in Organizational Behavior and Communication

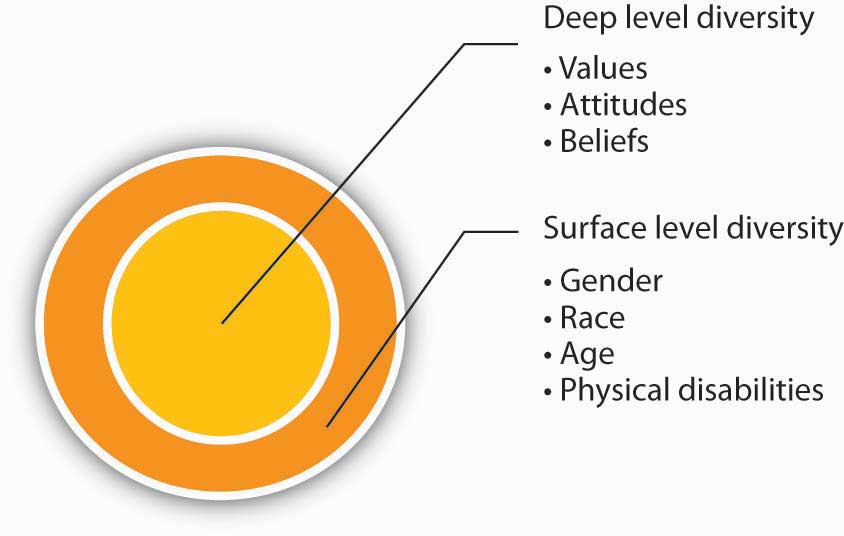

Diversity refers to the differences and similarities among individuals within a work environment. It encompasses characteristics such as gender, race, age, education, tenure, and functional background. While diversity can manifest in many forms, this discussion focuses on demographic characteristics that are relatively stable and visible—specifically gender, race, age, religion, physical abilities, and sexual orientation. These traits often shape how individuals experience organizational life and influence team dynamics, leadership, and communication (Randel, 2025).

Despite widespread recognition of diversity’s benefits—including enhanced creativity, innovation, and decision-making—many organizations struggle to manage it effectively. This is reflected in the 81,055 discrimination complaints filed with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) in 2023, which include claims based on race, gender, age, disability, and other protected characteristics (EEOC, 2023). These numbers likely underrepresent the true scope of workplace discrimination, as many incidents go unreported due to subtlety or lack of awareness, such as pay inequities or exclusion from advancement opportunities.

Recent research emphasizes that diversity efforts are most successful when embedded into core strategy, rather than treated as peripheral programs. Organizations that signal sincere commitments to equity—through both statements and actions—are more likely to foster employee engagement and trust (Volpone et al., 2025). Moreover, inclusive climates reduce the need for performative gestures and instead promote authentic dialogue and collaboration.

Resistance to diversity initiatives often stems from system justification theory, which suggests individuals may defend the status quo to preserve their self-image and group identity (Liaquat & Balcetis, 2023). To counter this, experts recommend framing diversity in terms of shared values—such as fairness and opportunity—rather than zero-sum narratives. This approach helps build consensus and reduces backlash.

Cross-cultural considerations are also essential, especially in global organizations. Countries without robust anti-discrimination laws may normalize exclusionary practices, making it critical for multinational companies to adopt culturally sensitive and legally compliant diversity strategies. As workplace demographics shift and legal landscapes evolve, organizations must remain agile and informed to create environments where all individuals feel valued and respected.

Benefits of Diversity

What is the business case for diversity? Having a diverse workforce and managing it effectively have the potential to bring about a number of benefits to organizations.

Enhanced Creativity and Innovation in Decision-Making

Diverse teams consistently demonstrate greater creativity and innovation in decision-making processes due to the variety of perspectives, experiences, and cognitive approaches they bring to the table. This diversity fosters richer dialogue, challenges groupthink, and encourages the exploration of unconventional solutions. According to Hundschell, Razinskas, Backmann, and Hoegl (2022), diversity enhances creativity at individual, team, and organizational levels, especially when supported by inclusive communication climates that promote psychological safety and open idea exchange. However, the relationship between diversity and creativity is complex and influenced by factors such as the observability and job-relatedness of diversity attributes. For example, unobservable attributes (e.g., values, cognitive styles) tend to have a stronger positive impact on creativity than visible ones (e.g., age, gender), particularly when teams are encouraged to engage in cross-level collaboration and dynamic communication (Hundschell et al., 2022). Organizations that cultivate inclusive environments—where diverse voices are actively heard and integrated—are better positioned to make innovative decisions that reflect a broader range of stakeholder needs.

Improved Customer Insight and Market Responsiveness

Organizations with diverse workforces are better equipped to understand and respond to the needs of increasingly heterogeneous customer bases. Diversity within teams enhances cultural intelligence, enabling companies to tailor products, services, and messaging to reflect the lived experiences of varied demographic groups. Recent research emphasizes that inclusive organizational communication—especially when it reflects authentic engagement with diverse communities—can significantly improve customer trust, loyalty, and market reach (Beckert & Koch, 2025).

Customer diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) is now recognized as a strategic marketing outcome, not just a workforce metric. Park, Voss, and Voss (2023) found that organizations with inclusive marketing actions and stakeholder-responsive communication strategies saw increased participation from underrepresented customer groups, particularly people of color. Their study also revealed that market-based assets—such as brand reputation and community relationships—play a critical role in shaping customer DEI outcomes when aligned with transparent and inclusive messaging.

Moreover, internal diversity communication influences external perceptions. When employees feel empowered to share insights from their cultural backgrounds, organizations gain access to nuanced customer perspectives that can inform product development and outreach strategies (Men et al., 2023). This dynamic feedback loop between internal inclusion and external responsiveness positions diversity as a driver of innovation and competitive advantage.

In contrast to earlier examples like PepsiCo and Harley-Davidson, today’s leading organizations are moving beyond surface-level representation to embrace deep-level diversity—including values, experiences, and communication styles—as a foundation for customer engagement. This shift reflects a broader understanding that authenticity and cultural fluency are essential for building meaningful relationships with diverse audiences (Beckert & Koch, 2025).

Greater Employee Engagement and Satisfaction

Employee engagement and satisfaction are strongly influenced by perceptions of fairness, inclusion, and communication climate within an organization. When employees feel valued and equitably treated, they are more likely to experience higher job satisfaction, stronger organizational commitment, and lower turnover intentions. Conversely, perceived discrimination or exclusion can lead to disengagement, stress, and diminished performance (Men, Qin, Mitson, & Thelen, 2023).

Recent research emphasizes the role of inclusive organizational communication in fostering engagement. Men et al. (2023) found that diversity communication efforts—such as transparent messaging, inclusive language, and cultural intelligence—significantly enhance employees’ perceptions of an inclusive climate. This inclusive climate, in turn, leads to higher levels of engagement, especially among minority employees. The study also revealed that inclusive communication has a disproportionately positive effect on engagement for employees from underrepresented groups, highlighting the importance of tailored messaging and authentic inclusion strategies.

Moreover, Saks and Gruman (2021) argue that employee engagement is not merely a psychological state but a dynamic process shaped by organizational practices, leadership communication, and social exchange. When organizations invest in two-way communication, feedback mechanisms, and recognition, they create conditions that support psychological presence and meaningful work—key drivers of engagement.

In today’s diverse and hybrid work environments, communication strategies that promote belonging, transparency, and voice are essential. Organizations that prioritize inclusive communication not only improve employee satisfaction but also build resilient cultures that support innovation, collaboration, and long-term retention.

Stronger Organizational Reputation and Brand Equity

Organizations that authentically integrate diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) into their core strategy are increasingly recognized as ethical leaders and rewarded with stronger brand equity, stakeholder trust, and market performance. Recent research shows that inclusive communication practices—such as transparent messaging, consistent DEI signaling, and stakeholder engagement—play a critical role in shaping public perception and investor confidence (Beckert & Koch, 2025).

In today’s climate, consumers and investors are closely watching how companies communicate their DEI commitments. According to the Edelman Trust Barometer, 68% of consumers expect brands to promote diversity and social responsibility, and companies that do so experience higher customer loyalty and advocacy (Edelman, 2024). Public missteps or perceived inauthenticity—such as diversity-washing or performative statements—can lead to reputational damage and viral backlash, underscoring the importance of strategic and sincere communication (Beckert & Koch, 2025).

From an investor standpoint, DEI is increasingly viewed as a signal of strong governance and long-term resilience. McKinsey & Company (2023) found that companies with diverse leadership teams are significantly more likely to outperform their peers financially. Moreover, shareholder demands for DEI transparency in annual reports have surged, with firms that demonstrate measurable progress in representation and equity receiving favorable market responses (Bloomberg, 2025).

Organizational communication scholars emphasize that brand reputation is not built solely on outcomes, but on how those outcomes are communicated. Companies that embed DEI into their storytelling, leadership messaging, and stakeholder dialogue are better positioned to navigate complex challenges and maintain credibility across diverse audiences (Wingard, 2025).

Improved Organizational Performance and Agility

Effective diversity management is increasingly recognized as a strategic asset that enhances organizational performance and agility. While poor diversity practices can lead to costly litigation and reputational damage, current research emphasizes that inclusive communication and leadership are key enablers of adaptability, innovation, and resilience. A 2024 meta-analysis found that organizations implementing diversity and inclusion (D&I) initiatives experience measurable improvements in decision-making, employee engagement, and productivity—especially when those initiatives are supported by transparent communication and leadership accountability (Okatta, Ajayi, & Olawale, 2024).

Organizational agility—the ability to adapt quickly to changing environments—is strongly linked to inclusive structures and communication strategies. Asghar, Kanbach, and Kraus (2025) reconceptualize agility as a multidimensional capability that includes workforce agility, strategic agility, and innovation agility. Their research shows that organizations with inclusive cultures and open communication channels are better equipped to reconfigure operations, respond to market shifts, and sustain competitive advantage. These findings suggest that diversity is not just a legal or ethical concern, but a dynamic capability that drives organizational success.

Moreover, inclusive communication reduces the risk of internal conflict and legal exposure. When employees feel heard, respected, and fairly treated, they are less likely to disengage or pursue legal action. The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) reported over 81,000 discrimination complaints in 2023, underscoring the financial and reputational risks of neglecting diversity and inclusion (EEOC, 2023). Proactive communication strategies—such as feedback loops, inclusive messaging, and conflict resolution protocols—can mitigate these risks and foster a culture of trust and accountability.

In today’s rapidly evolving workplace, agility is not just about speed—it’s about responsiveness, inclusion, and strategic alignment. Organizations that embed diversity into their communication practices and leadership models are better positioned to thrive in uncertainty, attract top talent, and build lasting stakeholder relationships.

Higher Company Performance

Organizations that effectively manage diversity and embed inclusive communication practices into their culture consistently demonstrate stronger performance outcomes. Recent research confirms that diversity—particularly when supported by transparent, inclusive messaging and leadership accountability—enhances innovation, decision-making, and financial results. A 2025 study by Kumar and Singh found that cultural, gender, and linguistic diversity positively influence organizational performance when aligned with inclusive communication and value systems, leading to improved collaboration, employee commitment, and business success.

McKinsey & Company (2023) reinforced this link, reporting that companies in the top quartile for ethnic and gender diversity in executive teams were 36% more likely to outperform their peers in profitability. These findings suggest that diversity is not just a moral imperative but a strategic advantage when integrated into organizational design and communication (McKinsey & Company, 2023). Moreover, inclusive communication fosters psychological safety and trust, which are essential for high-performing teams (Men, Qin, Mitson, & Thelen, 2023).

The relationship between diversity and performance is especially strong in environments that encourage open dialogue, shared values, and participative leadership. As organizational agility becomes increasingly important, diverse teams—supported by inclusive communication—are better equipped to respond to change, innovate, and sustain competitive advantage (Asghar, Kanbach, & Kraus, 2025).

Challenges of Diversity

If managing diversity effectively has the potential to increase company performance, increase creativity, and create a more satisfied workforce, why aren’t all companies doing a better job of encouraging diversity? Despite all the potential advantages, there are also a number of challenges associated with increased levels of diversity in the workforce.

Similarity-Attraction Phenomenon

One of the most enduring dynamics in human interaction is the tendency for individuals to be attracted to those who are similar to themselves—a concept known as the similarity-attraction hypothesis (SAH). This phenomenon continues to shape workplace relationships and communication patterns. Recent research confirms that individuals are more likely to seek out and communicate with colleagues who share similar demographic or psychological traits, such as race, age, gender, or values (Abbasi, Billsberry, & Todres, 2024). These preferences can lead to selective communication, reduced collaboration across diverse groups, and the reinforcement of in-group biases.

The SAH also contributes to emotional conflict and perceived exclusion in diverse teams. Employees who differ from their team members in visible traits often report feeling marginalized, overlooked, or unfairly treated—especially during early tenure when surface-level diversity is most salient (Salas-Schweikart et al., 2024). These perceptions can hinder team cohesion and increase turnover risk. While deep-level similarities (e.g., shared values or work styles) may eventually override surface-level differences, initial impressions based on demographic traits often shape early interactions and access to opportunities.

In hiring and promotion decisions, similarity-attraction can lead to affinity bias, where decision-makers favor candidates who resemble themselves, even when less qualified. This bias disproportionately affects underrepresented groups, particularly in organizations where leadership remains demographically homogeneous (Abbasi et al., 2024). Mentorship dynamics are similarly affected: without formal mentoring programs, employees tend to form relationships with mentors who share their background, limiting access for those who are demographically different (Wingard, 2025).

Organizational communication scholars emphasize that surface-level diversity often serves as a proxy for deep-level traits, especially in early interactions. Because individuals cannot immediately assess values or beliefs, they rely on visible cues to infer compatibility. This heuristic can lead to misjudgments and exclusion, particularly in diverse teams where assumptions about others may not reflect reality (Salas-Schweikart et al., 2024). Over time, as interpersonal familiarity grows, deep-level traits become more influential, and the effects of surface-level diversity diminish.

To mitigate the negative effects of similarity-attraction, organizations must adopt intentional communication strategies. These include onboarding practices that foster early inclusion, formal mentoring programs that ensure equitable access, and leadership training that raises awareness of unconscious bias. By creating environments where diverse employees feel seen and supported from the outset, organizations can reduce turnover, improve collaboration, and unlock the full potential of their workforce.

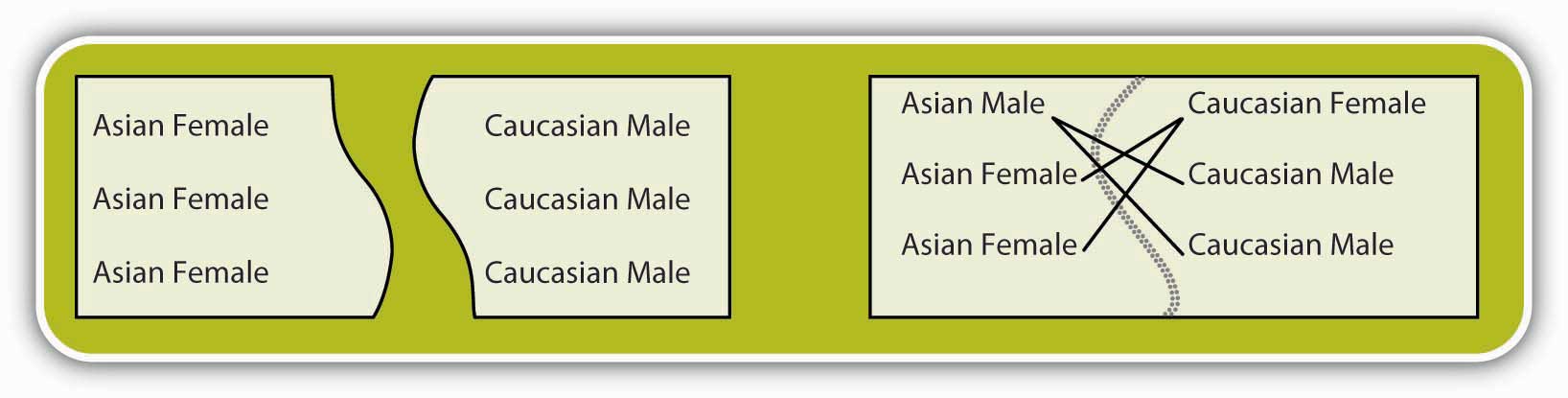

Faultlines

A faultline is a hypothetical dividing line that splits a group into subgroups based on one or more aligned attributes—such as gender, age, race, or functional background. For example, in a team with three older women and three younger men, both gender and age may combine to form a strong faultline, creating two distinct subgroups. These divisions can lead to ingroup-outgroup dynamics, where members identify more strongly with their subgroup and communicate less frequently across lines of difference (Homan & van Knippenberg, 2025).

Recent research emphasizes that faultlines are not inherently detrimental but become problematic when they activate social categorization processes that reduce trust, cohesion, and shared understanding. When faultlines are salient, teams may experience communication avoidance, emotional conflict, and reduced creativity—especially if subgroup identities overshadow collective goals (van Knippenberg, Dawson, West, & Homan, 2011). However, faultlines are more likely to emerge in diverse teams only when multiple diversity dimensions align (e.g., age and gender), and not all diverse teams experience these effects.

Importantly, bridging attributes—such as shared tenure or overlapping values—can mitigate faultline activation. For instance, if one older male member shares age with older female colleagues, age may serve as a cross-cutting characteristic that fosters connection across gender lines. This structural nuance can reduce subgroup isolation and promote more inclusive communication (Lau & Murnighan, 1998).

Organizational communication scholars have also identified strategies to manage faultlines effectively. Establishing shared objectives and inclusive norms can buffer against the negative effects of subgroup division. When teams are guided by a common purpose and encouraged to engage in open dialogue, faultlines become less salient and collaboration improves (van Knippenberg et al., 2011). Additionally, norms that discourage pre-meeting subgroup discussions—where members debate issues privately before group deliberation—can enhance decision quality by ensuring all perspectives are heard in the collective setting (Sawyer, Houlette, & Yeagley, 2006).

In sum, faultlines are a powerful lens for understanding team dynamics, but their impact depends on how organizations structure teams and foster inclusive communication. By promoting shared goals, cross-cutting relationships, and open dialogue, leaders can transform potential divisions into sources of strength.

Stereotypes

One of the most persistent challenges in managing a diverse workforce is the influence of stereotypes—generalized beliefs about groups that often lead to unfair and inaccurate decision-making. For example, the assumption that women are more relationship-oriented while men are more assertive may cause hiring managers to favor male candidates for leadership roles, regardless of individual qualifications. These biases are often applied unconsciously and can shape communication, evaluation, and advancement decisions in ways that disadvantage underrepresented groups (Ross, Traylor, & Ruggs, 2025).

Recent research in organizational communication emphasizes that stereotypes are not just cognitive shortcuts but are embedded in communication climates and signaling behaviors. Hofhuis and Vietze (2025) argue that stereotypes influence how individuals interpret messages, assign credibility, and engage with colleagues across cultural and demographic lines. When stereotypes are activated, they can distort interpersonal communication, reduce trust, and reinforce exclusionary norms—especially in diverse teams where intercultural competence is essential.

Moreover, stereotypes are often perpetuated through organizational signals, such as who is promoted, who receives mentoring, and how diversity is discussed in internal messaging. Ross et al. (2025) highlight that employees assess the sincerity of diversity efforts based on both verbal and nonverbal signals. When organizations fail to challenge stereotypes through inclusive communication and equitable practices, employees may perceive diversity initiatives as performative or insincere, undermining engagement and trust.

To counteract the effects of stereotypes, organizations must foster bias-aware communication environments. This includes training managers to recognize and interrupt biased assumptions, implementing structured decision-making protocols, and promoting diverse representation in leadership and messaging. Inclusive communication strategies—such as storytelling, transparency, and active listening—can help dismantle stereotypes and create space for more accurate, individualized assessments of employee potential.

Ultimately, awareness is only the first step. Organizations must move beyond passive recognition of stereotypes to actively reshape communication norms and decision-making processes. By doing so, they can reduce bias, improve equity, and unlock the full potential of a diverse workforce.

Specific Diversity Issues

Different demographic groups face unique work environments and varying challenges in the workplace. In this section, we will review the particular challenges associated with managing gender, race, religion, physical ability, and sexual orientation diversity in the workplace.

Gender Equity and Identity Inclusion

In the United States, foundational legislation such as the Equal Pay Act of 1963 and Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 prohibit gender-based discrimination in compensation and employment decisions. Despite these legal protections, gender disparities persist in the workplace, particularly in areas such as pay equity, leadership access, and identity inclusion. Women, transgender, and nonbinary employees often face systemic barriers that limit advancement and affect workplace well-being.

Recent research in organizational communication highlights the importance of gender-work identity integration—the ability to reconcile one’s gender identity with professional roles. A supportive organizational climate that promotes gender equality has been shown to improve women’s well-being and reduce identity conflict (Di Marco et al., 2025). This integration is especially critical in environments where gender norms are rigid or leadership remains demographically homogeneous.

Beyond binary gender dynamics, inclusive organizations are increasingly recognizing the importance of gender diversity and expression. The American Psychological Association (APA) emphasizes the use of inclusive language and policies that affirm transgender and nonbinary identities, such as gender-neutral job titles, pronoun visibility, and equitable access to benefits (APA, 2023). These practices not only foster psychological safety but also signal organizational commitment to equity.

Communication plays a pivotal role in shaping perceptions of fairness and inclusion. When gender equity is embedded in internal messaging, leadership behavior, and performance evaluations, employees are more likely to feel valued and supported. Conversely, inconsistent or performative messaging can undermine trust and reinforce exclusionary norms (Ross, Traylor, & Ruggs, 2025).

To advance gender equity and identity inclusion, organizations must move beyond compliance and adopt strategic communication frameworks that promote transparency, representation, and belonging. This includes training managers to recognize bias, implementing inclusive feedback systems, and ensuring that gender diversity is reflected in leadership, storytelling, and decision-making processes.

Intersectional Pay Equity

Despite longstanding legislation such as the Equal Pay Act of 1963 and Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, pay disparities persist across gender, race, disability status, and other identity dimensions. While the gender earnings gap remains a widely discussed issue—with women earning approximately 83% of what men earned in full-time roles in 2022 (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2023)—recent research emphasizes that this gap is not uniform. Instead, it is shaped by intersectional factors that compound disadvantage for women of color, LGBTQ+ individuals, and employees with disabilities (APA, 2023; Kumar & Singh, 2025).

Traditional explanations for the earnings gap—such as career interruptions due to caregiving, occupational segregation, and negotiation behavior—offer partial insight. However, they fail to account for structural and communicative biases that influence hiring, promotion, and compensation decisions. For example, women are less likely to negotiate starting salaries, and when they do, they often face social penalties or diminished outcomes (Bowles, Babcock, & Lai, 2007). These dynamics are exacerbated for women of color, who may experience double jeopardy due to racial and gender stereotypes in organizational communication (Ross, Traylor, & Ruggs, 2025).

Intersectional pay equity requires organizations to move beyond surface-level diversity metrics and examine how communication practices, leadership messaging, and workplace norms reinforce inequities. Research shows that inclusive communication—such as transparent pay policies, bias-aware performance reviews, and equitable access to mentorship—can reduce disparities and improve employee trust (Men, Qin, Mitson, & Thelen, 2023). Moreover, organizations that collect and analyze disaggregated compensation data by race, gender identity, and disability status are better equipped to identify and address systemic gaps (Park, Voss, & Voss, 2023).

The American Psychological Association (APA) emphasizes that intersectionality is not simply the sum of multiple identities, but a framework for understanding how interlocking systems of oppression and privilege shape individual experiences (APA, 2023). For example, a Black woman may face unique barriers that differ from those experienced by White women or Black men, and these distinctions must be reflected in organizational equity efforts.

In sum, intersectional pay equity is not just a legal or ethical concern—it is a communication imperative. Organizations must adopt inclusive language, transparent practices, and culturally responsive leadership to ensure that all employees are compensated fairly and valued equally.

Leadership Access and the Glass Cliff

While women make up nearly half of the U.S. workforce, they remain significantly underrepresented in senior leadership roles. As of 2022, only 53 of the Fortune 500 companies—just over 10%—had female CEOs (Elting, 2023). This disparity reflects the enduring presence of the glass ceiling, a metaphor for the invisible barriers that prevent women from advancing into top executive positions. Compounding this issue is the glass cliff phenomenon, which suggests that when women do attain leadership roles, they are more likely to be appointed during times of organizational crisis or instability, placing them in precarious positions with heightened risk of failure (Morgenroth, Kirby, Ryan, & Sudkamper, 2020).

Recent meta-analyses confirm that women and other underrepresented groups are disproportionately selected for leadership roles in high-risk contexts, particularly in countries with greater gender inequality (Morgenroth et al., 2020). However, newer research suggests that the glass cliff may not be uniformly present across all industries or organizations. For example, Li et al. (2024) found no consistent evidence of the glass cliff in U.S. corporations when controlling for organizational domain and selection criteria, indicating that the phenomenon may be context-dependent.

Organizational communication plays a critical role in perpetuating or challenging these leadership barriers. Gendered stereotypes—such as the belief that men are more assertive and women more relational—continue to influence perceptions of leadership suitability. These stereotypes are often embedded in managerial discourse, performance evaluations, and informal communication networks, leading to biased attribution of success and unequal access to advancement opportunities (Ross, Traylor, & Ruggs, 2025). For instance, when team contributions are ambiguous, managers are more likely to credit male employees for success in traditionally masculine tasks, such as financial analysis or strategic planning (Heilman & Haynes, 2005).

To address these disparities, organizations must adopt inclusive leadership development strategies and bias-aware communication practices. This includes formal mentorship programs, transparent promotion criteria, and leadership messaging that affirms diverse leadership styles. Companies such as Abbvie, Horizon, and S&P Global have been recognized for offering gender-neutral parental leave, fertility support, and mental health benefits—policies that signal commitment to gender equity and support for diverse family structures (100 Best Companies, 2022).

Ultimately, dismantling the glass ceiling and mitigating the glass cliff require more than representation—they demand structural change and inclusive communication that challenge stereotypes, promote equity, and create sustainable pathways to leadership for all genders.

Racial Equity and Antiracist Communication

Race remains a legally protected characteristic under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which prohibits discrimination in all employment-related decisions. Yet despite decades of legal protections, racial discrimination continues to manifest in hiring, promotion, compensation, and workplace culture. Recent studies confirm that racial bias persists even at senior levels, with minority professionals reporting exclusion from key assignments and exposure to racial microaggressions (Ross, Traylor, & Ruggs, 2025).

Ethnic minorities face both an earnings gap and a glass ceiling. In 2022, African American men earned approximately 76 cents and Hispanic men 75 cents for every dollar earned by White men (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2023). Representation in leadership remains disproportionately low: only eight Black CEOs led Fortune 500 companies as of 2023 (McGlauflin, 2023). These disparities are especially concerning given demographic shifts—by 2045, the U.S. is projected to become a majority-minority nation (Frey, 2021).

Organizational communication plays a pivotal role in either reinforcing or dismantling racial inequities. Research shows that antiracist signaling—the combination of public statements and concrete actions—significantly increases employee trust and commitment to diversity, especially among Black employees (Volpone, Casper, Wayne, & White, 2025). However, performative gestures without structural change can backfire, leading to skepticism and disengagement.

Bias in hiring remains a persistent issue. Bertrand and Mullainathan’s (2004) landmark résumé study revealed that applicants with White-sounding names received 50% more callbacks than those with African American-sounding names, despite identical qualifications. These findings continue to be echoed in more recent audits and highlight the need for bias-aware recruitment practices and inclusive messaging throughout the hiring process.

Perceptions of organizational diversity climate strongly influence minority employee outcomes. When employees believe their organization values diversity, they report higher satisfaction, lower turnover, and stronger performance (Men, Qin, Mitson, & Thelen, 2023). Conversely, environments perceived as indifferent or hostile to diversity contribute to absenteeism, disengagement, and attrition (McKay, Avery, & Morris, 2008).

One notable turnaround story is Denny’s Corporation, which transformed its reputation following a $54 million race discrimination settlement in 1991. By implementing diversity training, appointing a chief diversity officer, and expanding recruitment to historically Black colleges and universities, Denny’s increased minority representation in leadership and improved customer satisfaction among African Americans from 30% to 80% (Speizer, 2004).

In sum, racial equity is not achieved through policy alone—it requires intentional, inclusive communication, leadership accountability, and sustained structural reform. Organizations must move beyond symbolic gestures to embed antiracism into their culture, strategy, and everyday interactions.

Multigenerational Inclusion and Age Equity

The global workforce is undergoing a significant demographic shift. In the United States, employees aged 55 and older are projected to comprise 25% of the workforce by 2024 (Center for Workforce Inclusion, 2023). Similar trends are evident worldwide: OECD data show that 63% of the global workforce is aged 55–64, while 79% falls within the 25–54 age range (OECD, 2023). These figures reflect a growing need for organizations to embrace age diversity and generational inclusion as strategic imperatives.

Older employees contribute positively to workplace performance through higher levels of organizational citizenship, compliance with safety protocols, and lower rates of absenteeism and counterproductive behaviors (Ng & Feldman, 2008). They also demonstrate greater job stability, even when dissatisfied (Hellman, 1997). However, despite these strengths, age-related stereotypes persist. Younger workers often perceive older colleagues as less adaptable or less capable, even though such assumptions have been widely refuted by empirical research (Posthuma & Campion, 2009).

Ageism remains a challenge in organizational communication and culture. According to the World Health Organization, one in two people globally holds ageist attitudes (de la Fuente-Núñez & Mikton, 2021). In the workplace, this manifests in exclusion from training, biased promotion decisions, and assumptions about retirement readiness. A Harris Poll found that 34% of working adults believe ageism is a problem in their workplace, and 31% have experienced it personally (Rosanwo, 2021). These biases affect not only older workers but also younger professionals, who report being dismissed as inexperienced or uncommitted (Bratt, Abrams, & Swift, 2020).

Organizational communication scholars emphasize that inclusive messaging and leadership behavior are essential for bridging generational divides. Strawser, Smith, and Rubenking (2021) argue that multigenerational teams thrive when communication is tailored to diverse preferences and when leaders foster environments of mutual respect and shared purpose. For example, Gen Z employees may prefer visual and interactive communication platforms, while Baby Boomers may favor structured formats like PowerPoint or email (Andrade, 2023).

Generational diversity also influences perceptions of fairness and organizational justice. Colquitt, Noe, and Jackson (2002) found that different age groups interpret fairness differently, which can lead to misunderstandings and conflict. To address this, organizations must implement age-inclusive HR practices, such as flexible work arrangements, cross-generational mentoring, and inclusive training programs (Bailey & Owens, 2020).

Companies like Lockheed Martin and Novo Nordisk have successfully adapted their management styles to accommodate generational differences in feedback and learning preferences. These efforts reflect a broader trend toward intergenerational collaboration, where knowledge flows bidirectionally—older employees share experience and younger employees contribute digital fluency and innovation (Bailey & Owens, 2020).

In sum, multigenerational inclusion is not just about avoiding age discrimination—it’s about leveraging the unique strengths of each generation through intentional communication, inclusive leadership, and adaptive workplace design. As the workforce continues to age and diversify, organizations that embrace age equity will be better positioned to thrive.

Religious Accommodation and Belief Inclusion

Religion is a legally protected characteristic under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which prohibits employment discrimination based on religious beliefs and practices. Employers are required to provide reasonable accommodations for religious observance unless doing so would impose an undue hardship on business operations (EEOC, 2023). The Supreme Court’s 2023 decision in Groff v. DeJoy clarified that undue hardship must involve a substantial burden, not merely a minor inconvenience, raising the bar for denying religious accommodations (U.S. Office of Personnel Management, 2025).

Religious accommodation often involves adjustments to scheduling, attire, and workplace practices. For example, Muslim employees may request prayer breaks throughout the day, while Jewish employees may seek time off for holidays not recognized federally. Similarly, religious dress—such as hijabs, turbans, or yarmulkes—may require exceptions to grooming policies. These accommodations are increasingly viewed not only as legal obligations but as strategic inclusion practices that foster employee engagement and trust (Puttaki, 2023).

Organizational communication scholars emphasize that open dialogue and inclusive messaging are essential for managing religious diversity. Dik, Daniels, and Alayan (2024) argue that religion and spirituality shape how individuals experience meaning at work, and that inclusive communication can enhance well-being, reduce conflict, and promote belonging. However, many organizations still struggle to integrate religious inclusion into broader diversity frameworks, often due to discomfort or lack of awareness.

Recent federal guidance encourages agencies and employers to adopt flexible work arrangements—such as telework, maxiflex schedules, and religious compensatory time off—to support religious observance without compromising productivity (U.S. Office of Personnel Management, 2025). These accommodations are especially relevant in hybrid and remote work environments, where flexibility can be a low-cost solution to meet religious needs.

Importantly, religious inclusion must extend beyond dominant faiths. The EEOC recognizes that nontraditional or minority religions—such as the Church of Body Modification—are equally protected under Title VII, as long as beliefs are sincerely held. In EEOC v. Costco, the court ruled in favor of the employer after it made a good-faith effort to accommodate an employee’s religious expression by offering a compromise on dress code enforcement (EEOC, 2023).

In sum, religious accommodation is not just a compliance issue—it is a communication challenge and inclusion opportunity. Organizations that proactively engage in respectful dialogue, flexible policy design, and inclusive messaging are better equipped to support employees of all faiths and foster a culture of belonging.

Disability Inclusion and Accessibility Innovation

Disability inclusion is a critical dimension of workplace equity, yet it remains underrepresented in many organizational diversity efforts. In 2022, over 25,000 disability-related discrimination complaints were filed with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC), underscoring the persistent barriers faced by employees with physical, mental, and invisible disabilities (EEOC, 2023). The Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 (ADA) mandates that employers provide reasonable accommodations for qualified individuals, including assistive technologies, flexible scheduling, and job restructuring.

Recent research emphasizes that disability inclusion must go beyond compliance to become a strategic and communicative priority. Praslova (2023) argues that organizations must shift from the medical model—which views disability as an individual deficit—to the social model, which recognizes that exclusion is often a product of environmental and attitudinal barriers. This reframing requires inclusive communication practices, universal design principles, and leadership accountability.

Employees with chronic conditions or mental health disabilities—such as PTSD, anxiety, or depression—are particularly vulnerable to stereotyping, underemployment, and isolation. These individuals are often relegated to roles below their qualifications and experience higher turnover rates (Beatty & Joffe, 2006). To counter this, organizations must foster psychological safety, where employees feel comfortable disclosing disabilities and requesting accommodations without fear of stigma (Talikowska, 2025).

The APA’s Accessibility and Inclusion Maturity Model (AIMM) offers a science-based framework for embedding disability inclusion across organizational systems. It encourages proactive strategies such as inclusive hiring, disability-focused employee resource groups, and leadership development programs for disabled professionals (APA, 2024). Moreover, reverse mentoring—where senior leaders learn directly from disabled employees—has emerged as a powerful tool for transforming organizational culture and bridging communication gaps (Talikowska, 2025).

Supportive relationships with supervisors and peers remain essential. Colella and Varma (2001) found that proactive rapport-building and inclusive leadership behaviors significantly improve the workplace experience for employees with disabilities. In today’s hybrid and remote environments, accessible communication tools, such as real-time captioning and screen readers, are vital for ensuring full participation.

Ultimately, disability inclusion is not just a legal obligation—it is a communication imperative and innovation driver. Organizations that embrace accessibility as a core value are better positioned to attract diverse talent, enhance employee engagement, and build resilient, future-ready cultures.

LGBTQ+ Inclusion and SOGI Representation

LGBTQ+ employees continue to face systemic barriers in the workplace, including discrimination, invisibility, and exclusion. The landmark 2020 Supreme Court decision in Bostock v. Clayton County clarified that Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 prohibits employment discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity (Equal Employment Opportunity Commission [EEOC], 2021). While this ruling marked a significant legal milestone, workplace inclusion remains uneven and often performative.

One of the most pressing challenges is the disclosure of sexual orientation and gender identity (SOGI). Research shows that fear of disclosure—not disclosure itself—is the strongest predictor of negative workplace outcomes. LGBTQ+ employees who worry about revealing their identity report lower job satisfaction, reduced organizational commitment, and higher turnover intentions (Ragins, Singh, & Cornwell, 2007). This underscores the importance of cultivating psychologically safe environments where employees feel respected and affirmed.

Recent studies emphasize that inclusive organizational communication—including visible support, inclusive language, and equitable policies—plays a critical role in shaping LGBTQ+ employees’ experiences. Ross, Traylor, and Ruggs (2025) found that employees assess the sincerity of diversity efforts based on both verbal and nonverbal signals. When organizations fail to back up statements with action, LGBTQ+ employees may perceive inclusion efforts as hollow or insincere.

One powerful strategy for inclusion is the collection and use of SOGI data. While controversial, responsible SOGI data collection can improve visibility, inform benefits design, and support culturally competent services. However, van der Toorn et al. (2024) caution that SOGI data collection must balance inclusion with protection, addressing privacy concerns and potential harm. Engaging LGBTQ+ stakeholders in the design and implementation of data practices is essential.

Organizations can also demonstrate commitment through inclusive benefits, such as gender-affirming healthcare, domestic partner coverage, and mental health support tailored to LGBTQ+ needs. A 2025 industry survey found that 93% of Chief Diversity Officers believe LGBTQ+ employees are the group most in need of active support from the private sector, especially in light of recent political rollbacks and rising hostility toward gender-diverse individuals.

Ultimately, LGBTQ+ inclusion is not a seasonal campaign—it is a year-round commitment to equity, dignity, and belonging. Organizations that align their internal culture with external messaging, elevate LGBTQ+ voices, and embed inclusion into everyday communication are better positioned to attract and retain diverse talent.

Neurodiversity and Cognitive Inclusion

Neurodiversity refers to the naturally occurring variation in human cognition, encompassing conditions such as autism, ADHD, dyslexia, dyspraxia, and other neurological differences. Rather than viewing these traits as deficits, the neurodiversity movement frames them as valuable forms of human diversity that contribute unique strengths to the workplace (Austin et al., 2025). Cognitive inclusion, therefore, involves designing environments and communication practices that support neurodivergent employees in thriving—not just surviving.

Recent research emphasizes that neuroinclusion is not merely a diversity initiative but a strategic capability-building opportunity. Organizations that embrace neurodivergent talent report improvements in innovation, problem-solving, and team performance (Austin et al., 2025). For example, programs like SAP’s Autism at Work and EY’s Neuro-Diverse Centers of Excellence have demonstrated that neurodistinct employees often excel in pattern recognition, systems thinking, and detail-oriented tasks.

However, inclusion requires more than hiring—it demands intentional communication and structural redesign. Khan et al. (2023) propose a multistage framework for managing neurodiversity, which includes reconfiguring recruitment processes, fostering inclusive development practices, and ensuring equitable supervision. This approach helps mitigate common barriers such as sensory overload, rigid work expectations, and biased performance evaluations.

Disclosure remains a complex issue. Many neurodivergent employees hesitate to disclose their neurotype due to fear of stigma or misunderstanding. Kalmanovich-Cohen and Stanton (2025) argue that organizations should reduce reliance on disclosure by implementing universal design principles—such as flexible scheduling, quiet workspaces, and alternative communication formats—that benefit all employees regardless of diagnosis.

Language also matters. The APA’s Inclusive Language Guide (2023) recommends using terms like “neurodivergent” or “neurodistinct” rather than “disorder” or “impairment,” which carry stigmatizing connotations. Inclusive language signals respect and helps create psychologically safe environments where employees feel empowered to contribute authentically.

In sum, neurodiversity and cognitive inclusion are not just ethical imperatives—they are innovation drivers. Organizations that embed inclusive communication, flexible design, and neurodivergent leadership into their culture are better equipped to unlock the full potential of their workforce.

Socioeconomic Background and Class Inclusion

Socioeconomic status (SES) encompasses not only income but also educational attainment, occupational prestige, and subjective perceptions of social class. It shapes access to resources, opportunities, and workplace experiences—and remains one of the most underrecognized dimensions of diversity in organizational communication (APA, 2023). Employees from lower-income or working-class backgrounds often face invisible barriers, including exclusion from informal networks, biased assumptions about competence, and limited access to mentorship or advancement opportunities.

Recent research emphasizes that class-based bias is embedded in organizational language, norms, and leadership behavior. For example, hiring practices that favor elite educational credentials or polished communication styles may inadvertently exclude qualified candidates from nontraditional or first-generation backgrounds (Diemer et al., 2013). These biases are often unintentional but can reinforce systemic inequities and reduce workforce diversity.

Organizational communication scholars advocate for class-conscious inclusion strategies, such as:

- Avoiding deficit-based language (e.g., “underprivileged” or “low class”) in favor of person-first and context-aware descriptors (APA, 2023).

- Recognizing “opportunity gaps” rather than “achievement gaps” to highlight structural barriers rather than individual shortcomings.

- Creating inclusive onboarding and training programs that do not assume prior exposure to corporate norms or professional etiquette.

Moreover, intersectionality matters. SES often intersects with race, gender, disability, and other identities, compounding disadvantage. For example, a first-generation college graduate who is also a person of color may face layered challenges in navigating workplace culture and expectations (APA, 2023; Ferdman & Deane, 2014).

To foster class inclusion, organizations must:

- Expand recruitment pipelines to include community colleges, vocational programs, and nontraditional educational paths.

- Offer mentorship and sponsorship programs tailored to first-generation professionals.

- Train managers to recognize class-based bias and communicate inclusively across socioeconomic differences.

Ultimately, class inclusion is about recognizing lived experience as a source of insight and resilience, not a liability. Organizations that embrace socioeconomic diversity through inclusive communication and equitable practices are better equipped to build trust, foster innovation, and reflect the communities they serve.

Cultural and Linguistic Diversity

Cultural and linguistic diversity refers to the presence of individuals from varied ethnic, national, and language backgrounds within an organization. As globalization accelerates and migration patterns shift, workplaces are increasingly composed of employees who bring distinct cultural norms, communication styles, and linguistic repertoires. This diversity offers tremendous potential for innovation, market expansion, and intercultural competence—but only when supported by inclusive organizational communication (Hofhuis & Vietze, 2025).

Recent research emphasizes that the success of diversity management depends not only on hiring practices but also on the underlying motivations and communication strategies organizations use to foster inclusion. Hofhuis and Vietze (2025) argue that intercultural communication serves as a bridge between diversity perspectives and workplace outcomes. When organizations adopt inclusive diversity ideologies—such as multiculturalism or integration—they are more likely to foster trust, collaboration, and psychological safety across cultural lines.

Language plays a central role in shaping inclusion. Employees who speak a minority or non-dominant language may experience linguistic marginalization, especially when communication norms favor native speakers or monolingual formats. Shrivastava et al. (2022) found that culturally sensitive communication during organizational change significantly improves employee acceptance and engagement. Their framework highlights the importance of tailoring messages to reflect cultural values and linguistic preferences, particularly in multicultural teams.

The APA Inclusive Language Guide (2023) recommends avoiding language that assumes cultural homogeneity or reinforces stereotypes. For example, using terms like “non-native speaker” or “language barrier” can unintentionally stigmatize multilingual employees. Instead, organizations should adopt asset-based language that recognizes multilingualism as a strength and promotes linguistic equity in meetings, training, and documentation.

To support cultural and linguistic inclusion, organizations can:

- Provide translation and interpretation services for key communications.

- Encourage multilingual signage and documentation.

- Offer intercultural communication training for managers and teams.

- Create employee resource groups focused on cultural heritage and language advocacy.

Ultimately, cultural and linguistic diversity is not just a demographic reality—it is a strategic resource. Organizations that embrace inclusive communication and intercultural competence are better equipped to navigate global markets, foster innovation, and build resilient, diverse teams.

Workplace Strategy Pack

What Organizations Have the Right to Expect in Interviews

Objective

To clarify the expectations organizations can reasonably hold during interviews, ensuring candidates demonstrate professionalism, preparedness, and alignment with the role and company culture.

Why It Matters

Interviews are not just about evaluating candidates—they’re also a reflection of organizational identity and values. According to organizational communication research, interviews serve as a site of sensemaking, where both parties assess fit, credibility, and alignment (Weick, 1995). When candidates understand what’s expected, they’re more likely to engage authentically and effectively, contributing to better hiring outcomes and stronger organizational culture (Jablin, 2001).

Strategy Toolkit

| Organizational Expectation | What It Means for Candidates |

|---|---|

| Professionalism | Dress appropriately*, arrive on time, and communicate respectfully. |

| Preparedness | Research the company, understand the role, and bring thoughtful questions. |

| Relevant Self-Presentation | Share experiences and skills that directly relate to the job description. |

| Ethical Communication | Be honest about qualifications and employment history. |

| Engagement and Curiosity | Demonstrate interest in the organization’s mission, values, and future. |

| Respect for Boundaries | Avoid oversharing or steering the conversation into personal or inappropriate territory. |

*What Does “Dress Appropriately” Mean in a Job Interview?

“Dress appropriately” means wearing clothes that match the professional expectations of the company and the role you’re applying for. It’s about showing respect, making a good first impression, and signaling that you take the opportunity seriously.

Think of it like this: you wouldn’t wear gym clothes to a wedding, right? Same idea—your outfit should fit the occasion. First impressions happen fast—often within the first few seconds. Employers want to see that you understand their culture and can represent their brand. Dressing well shows confidence, maturity, and attention to detail.

What Should You Wear?

Here’s a quick guide based on the type of job:

| Job Type | What to Wear |

|---|---|

| Corporate (finance, law) | Suit and tie for men; blazer, blouse, and dress pants or skirt for women. |

| Creative (marketing, design) | Smart casual—think stylish but polished (e.g., button-down shirt, clean shoes). |

| Tech/startup | Business casual—neat jeans or slacks, collared shirt, no need for a full suit. |

| Retail or service | Clean, neat, and modest—no ripped jeans, graphic tees, or flashy accessories. |

Empowerment Tip

“You don’t need designer clothes—you just need to look like you care.”

Dressing appropriately isn’t about being fancy. It’s about showing up with intention and respect.

“Interviews are a mutual evaluation.” Candidates should feel empowered to meet expectations while also assessing whether the organization’s culture and communication style align with their own values and goals.

References

Jablin, F. M. (2001). Organizational entry, assimilation, and disengagement/exit. In F. M. Jablin & L. L. Putnam (Eds.), The new handbook of organizational communication: Advances in theory, research, and methods (pp. 732–818). SAGE Publications.

Weick, K. E. (1995). Sensemaking in organizations. SAGE Publications.

APA Style. (2024). APA Styleat https://apastyle.apa.org

Insider Edge

Responding to Illegal or Inappropriate Interview Questions

Objective

To equip job candidates with communication strategies to navigate interviews professionally and ethically when faced with illegal, inappropriate, or rule-violating questions.

Why It Matters

Interview questions are meant to assess qualifications—not personal identity. However, candidates are sometimes asked illegal questions about age, marital status, religion, disability, or national origin. These questions violate Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) guidelines and can signal deeper organizational issues. Research shows that ethical communication and psychological safety begin at the hiring stage, and how candidates respond can shape their future workplace experience (Tourish, 2020; Edmondson, 1999).

Strategy Toolkit

| Action | How to Use It |

|---|---|

| Stay Calm and Professional | Respond with composure. Avoid confrontation, but don’t feel obligated to answer. |

| Redirect the Conversation | Pivot to your qualifications. Example: “I’m happy to discuss how my experience aligns with the role.” |

| Ask for Clarification | If unsure, ask: “Could you clarify how that relates to the position?” This gives the interviewer a chance to reframe. |

| Know Your Rights | Familiarize yourself with EEOC guidelines and local laws. You are not required to answer illegal questions. |

| Document and Report if Needed | If the question was clearly discriminatory or persistent, consider reporting it to HR or relevant authorities. |

| Evaluate Cultural Fit | Consider whether you want to work for an organization that disregards ethical boundaries in hiring. |

Empowerment Tip

“An interview is a two-way evaluation.” If a company crosses ethical lines before you’re hired, it’s a signal—not just a slip. You deserve to work in a place that respects your boundaries and values your professionalism.

References\

Edmondson, A. C. (1999). Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44(2), 350–383. https://doi.org/10.2307/2666999

Tourish, D. (2020). The triumph of silence: Exploring the dark side of leadership and organizational communication. Oxford University Press.

Gillis, J. (n.d.). 15 common illegal interview questions. The Interview Guys. Retrieved August 12, 2025, from https://theinterviewguys.com/illegal-interview-questions/

Suggestions for Managing Demographic Diversity

Organizations committed to equity and inclusion must move beyond symbolic gestures and adopt strategic, evidence-based practices that address systemic barriers and foster belonging. Below are four updated strategies supported by current research:

Embedding Accountability into Leadership Structures

Holding managers accountable for diversity outcomes is essential for sustainable change. Katz and Gans (1998) emphasized that managers shape both employee experience and the success of organizational change. More recently, Anderson (2021) argued that accountability must be cultural—not just procedural—requiring leaders to acknowledge harm, repair relationships, and model inclusive behavior. Organizations should implement metrics-based accountability systems, tie diversity goals to performance evaluations, and foster a culture where inclusion is a shared responsibility. For example, some companies now use DEI dashboards that track hiring, retention, and promotion data by demographic group, with results reviewed quarterly by senior leadership.

Transforming Diversity Training into Experiential Learning

Traditional diversity training often fails to produce lasting change unless it is experiential, reflective, and embedded in organizational culture. Bezrukova, Spell, and Perry (2024) found that effective training must address systemic bias and be tailored to organizational context. Kuknor and Kumar (2024) propose a two-phase model: awareness training followed by skill-building interventions. Training should be ongoing, theory-informed, and linked to real-world decision-making. For example. companies are shifting toward immersive simulations, storytelling, and peer-led workshops that encourage empathy and perspective-taking.

Reimagining Recruitment Through an Equity Lens

Recruitment practices must be redesigned to eliminate bias and expand access. Nascimento et al. (2024) advocate for strategic recruitment aligned with long-term organizational goals, emphasizing inclusive pipelines and culturally responsive outreach. Li and Song (2018) highlight the importance of mutual understanding between recruiters and candidates, especially in diverse and global contexts. For example, organizations are partnering with community colleges, HBCUs, and affinity groups to diversify applicant pools and reduce reliance on elite networks.

Affirmative Action as a Strategic Equity Tool

Affirmative action programs remain a vital mechanism for addressing historical and systemic inequities. Crosby (2003) argued that affirmative action is proactive, ensuring fairness without requiring individuals to self-advocate in potentially risky environments. APA’s recent statements reaffirm the importance of race-conscious policies in building diverse and effective workforces, especially in healthcare and education (APA, 2023). For example, organizations are using affirmative action frameworks to audit representation, set equity goals, and ensure fair access to leadership development programs.

Types of Affirmative Action Programs

Affirmative action programs in employment vary widely in scope, legality, and organizational impact. As legal standards evolve and public scrutiny intensifies, organizations must carefully design and communicate these programs to promote equity while maintaining transparency and trust. Below are four commonly recognized categories, updated with recent legal developments and communication insights.

1. Elimination of Discrimination

Programs focused on eliminating discriminatory barriers remain foundational and legally required under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act. These initiatives emphasize fairness and compliance without invoking preferential treatment, making them broadly supported by employees (Cropanzano, Slaughter, & Bachiochi, 2005). For example, organizations are reviewing job descriptions to remove biased language and ensuring interview questions are strictly job-related.

2. Targeted Recruitment

Targeted outreach to underrepresented groups is still widely practiced and legally permissible, especially when framed as expanding access rather than guaranteeing outcomes (Kravitz, 2008). Communication research suggests that emphasizing shared benefits—such as stronger teams and broader talent pools—can enhance employee support (Turner & Pratkanis, 1994). For example, companies partner with HBCUs, tribal colleges, and disability advocacy organizations to diversify applicant pipelines.

3. Tie-Breaker Preference

In rare cases where candidates are equally qualified, organizations may consider identity factors as a “plus” in hiring decisions. However, such practices must meet strict legal standards of narrow tailoring and compelling interest, and they require clear documentation to avoid claims of reverse discrimination (Volpone et al., 2025; LegalClarity, 2025). For example, some institutions apply holistic review processes where race or gender may be considered as one factor among many, similar to past university admissions models.

4. Preferential Treatment

Preferential selection of less-qualified candidates based solely on demographic characteristics is generally prohibited under federal law and is increasingly viewed unfavorably by employees (Kravitz, 2008). The Supreme Court’s 2023 decision in Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard further restricted race-conscious practices in education, signaling caution for similar approaches in employment (LegalClarity, 2025). For example, hiring based solely on race or gender without regard to qualifications is legally risky and often counterproductive.

Communication Matters

Organizational communication research underscores the importance of framing affirmative action as inclusive and merit-enhancing. Effective messaging highlights how diversity benefits all employees, avoids zero-sum framing, and fosters a sense of shared responsibility (Turner & Pratkanis, 1994; Leonard & Grobler, 2004). Internal transparency and leadership modeling are key to building trust and sustaining support.

Workplace Strategy Pack

Thriving as “The Only” in the Room

Objective

To support employees who find themselves as the only representative of a particular identity in a workplace setting by offering strategies for confidence, connection, and communication.

Why It Matters

Being “the only” in a room can lead to feelings of isolation, hypervisibility, or pressure to represent an entire group. Organizational communication research shows that inclusion and psychological safety are essential for performance, engagement, and well-being (Edmondson, 1999). When employees feel seen and supported, they contribute more authentically and effectively to team dynamics (Allen et al., 2022).

Strategy Toolkit

| Challenge | Strategy |

|---|---|

| Feeling isolated | Build micro-connections—seek allies, mentors, or affinity groups. |

| Pressure to represent your group | Set boundaries. You don’t have to speak for everyone—just yourself. |

| Navigating bias or microaggressions | Use assertive communication: “I’d like to offer a different perspective.” |

| Lack of cultural understanding | Educate when you choose to—but know it’s not your job to fix the culture. |

| Imposter syndrome | Reframe your difference as a strength. You bring unique insight and value. |

Empowerment Tip

“You belong—not because you fit in, but because you bring something no one else does.”

Being different isn’t a deficit—it’s a distinction. Your perspective can challenge norms, spark innovation, and expand what’s possible.

Insider Edge

How to Tell If You’re Not Respecting a Colleague’s Diversity

Respecting diversity isn’t just about avoiding offensive behavior—it’s about actively creating space for others to feel seen, heard, and valued. Whether it’s race, gender, religion (including Christianity), disability, socioeconomic background, or even zip code, every identity shapes how people experience the workplace. So how can you tell if you’re unintentionally missing the mark?

Here are some signs—and what to do about them:

1. You Make Assumptions About Someone’s Background or Beliefs

Red flag: You assume someone celebrates certain holidays, grew up with similar values, or shares your views on gender roles or education. Respectful shift: Ask open-ended questions and listen. For example, “What’s your favorite tradition around this time of year?” instead of “Are you doing Christmas with your family?”

2. You Avoid Conversations About Identity

Red flag: You steer clear of topics like race, religion, or disability because you’re afraid of saying the wrong thing. Respectful shift: Silence can feel like erasure. Instead, educate yourself and engage with humility. A simple “I’d love to learn more about your perspective if you’re open to sharing” goes a long way.

3. You Use Humor That Relies on Stereotypes

Red flag: You joke about accents, gender roles, or regional quirks (“You’re from the South—bet you love sweet tea and guns!”). Respectful shift: Humor should build connection, not reinforce bias. If you’re unsure, skip the joke and opt for genuine curiosity.

🚩 4. You Treat Certain Credentials or Experiences as “Less Than”

Red flag: You subtly dismiss someone’s community college degree, military background, or rural upbringing. Respectful shift: Recognize that excellence comes in many forms. Ask about their journey and honor the resilience behind it.

5. You Speak Over or “Correct” Someone’s Identity