Chapter 3: Understanding Behavior at Work: Personality, Perception, and Values

Learning Objectives

- Define personality and explain its influence on workplace communication, motivation, and behavior.

- Analyze how personal and cultural values shape work attitudes and decision-making.

- Describe the perception process and its impact on interpersonal interactions and organizational judgments.

- Evaluate how individual differences—including personality, age, and identity—affect ethical reasoning.

- Explore cross-cultural influences on personality traits, value systems, and perceptual frameworks in the workplace.

Individuals bring a number of differences to work, such as unique personalities, values, emotions, and moods. When new employees enter organizations, their stable or transient characteristics affect how they behave and perform. Moreover, companies hire people with the expectation that those individuals have certain skills, abilities, personalities, and values. Therefore, it is important to understand individual characteristics that matter for employee behaviors at work.

Section 3.1: Spotlight

Hiring With Heart: Danni Eickenhorst’s People-First Philosophy

Figure 3.1

Daniel Schwen – Wikimedia Commons – CC BY 3.0.

In an era where employee loyalty and workplace culture can make or break an organization, St. Louis–based CEO Danni Eickenhorst has emerged as a powerful voice in people-centered leadership. As the co-founder and CEO of HuSTL Hospitality, she brings a holistic and values-driven approach to hiring—one that prioritizes potential, personal growth, and emotional intelligence over polished résumés. Her success across multiple ventures highlights how thoughtful hiring practices grounded in compassion, character, and community values can drive both business performance and social impact.

Eickenhorst’s hiring strategy is unconventional but deeply strategic. Rather than focusing solely on industry credentials or technical expertise, she seeks candidates with “heart, hustle, and humility.” She values individuals who demonstrate self-awareness, emotional resilience, and a genuine desire to grow—especially those who may have been overlooked by traditional hiring pipelines (Eickenhorst, 2022). This approach opens doors for candidates with non-linear career paths, including those from marginalized backgrounds, and creates space for their transformation within a supportive infrastructure.

In her leadership model, the so-called “perfect boss” isn’t someone who commands authority—it’s someone who uplifts. Eickenhorst has described her ideal leadership philosophy as “pouring into people,” a form of servant leadership that encourages mentorship, development, and shared accountability (Eickenhorst, 2023). She believes in building a work environment where employees aren’t just working for a paycheck, but are empowered to pursue bold personal and professional goals.

Another key tenet of her philosophy is the role of self-perception in team dynamics. Eickenhorst argues that employees who view themselves as capable and valuable are more likely to contribute proactively and take ownership of their roles. In contrast, negative self-perception can lead to withdrawal, hesitation, and disengagement. To support self-confidence, HuSTL Hospitality integrates consistent recognition, honest feedback, and opportunities for employees to succeed in visible, meaningful ways (HuSTL Hospitality, 2024).

Underlying Eickenhorst’s approach is a belief that success is not just about hiring the right people, but about becoming the kind of organization where people can thrive. She often speaks about aligning employee values with organizational mission—especially in industries like hospitality where burnout and turnover are common. Her company’s success demonstrates that investing in people, embracing diverse perspectives, and creating purpose-driven teams can lead to sustainable performance and powerful community impact.

Ultimately, Danni Eickenhorst’s advice for hiring successful employees is refreshingly clear: hire for character, build with compassion, and lead with trust. In doing so, organizations don’t just grow profits—they grow people.

References

Eickenhorst, D. (2022). Hiring for potential, not polish. LinkedIn. https://www.linkedin.com/in/dannieickenhorst

Eickenhorst, D. (2023). Pouring into your people: Leadership that lasts. HuSTL Hospitality Blog. https://www.hustlhospitality.com/blog

HuSTL Hospitality. (2024). Mission and culture. https://www.hustlhospitality.com/our-story

Discussion Questions

- Describe how self-perception can positively or negatively affect a work environment?

- What advice would you give a recent college graduate after reading about Danni Eichenhorst’s advice?

- What do you think about Eickenhorst’s hiring strategy?

- How would Eickenhorst describe a “perfect” boss?

- How would you describe a “perfect” boss?

Section 3.2: The Interactionist Perspective: The Role of Fit

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, you should be able to do the following:

- Analyze the distinctions between person–organization fit and person–job fit in organizational contexts.

- Evaluate how person–job fit influences employee work behaviors such as performance, satisfaction, and turnover.

- Assess the impact of person–organization fit on work behaviors, including organizational commitment and cultural alignment.

Section 3.2

The Interactionist Perspective: The Role of Fit

In organizational communication, understanding how individual traits interact with workplace environments is essential. While employees bring stable characteristics—such as personality, cognitive abilities, and behavioral tendencies—to their roles, context matters. According to the interactionist perspective, behavior is shaped by the dynamic interplay between the person and the situation (Kristof-Brown, Zimmerman, & Johnson, 2005). For example, a shy student may hesitate to speak in class, but if participation is highly encouraged, graded, and the environment feels psychologically safe, that same student may actively contribute. Similarly, a proactive and creative employee may thrive in a startup but feel stifled in a rigid, hierarchical organization.

This is why organizations assess two key types of fit during hiring and onboarding:

- Person–Job Fit refers to how well an individual’s skills, knowledge, and abilities align with the demands of a specific role.

- Person–Organization Fit reflects the compatibility between an individual’s values, personality, and goals with the broader organizational culture.

Both types of fit are linked to positive outcomes such as job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and retention (Cable & DeRue, 2002; Saks & Ashforth, 2002). For instance, someone who thrives on innovation may be a strong match for a tech company that rewards experimentation, but a poor fit for a role that emphasizes routine and predictability—like data auditing or compliance.

However, fit is not a one-size-fits-all predictor of performance. While some studies show that person–organization fit correlates with job performance, others suggest the relationship is inconsistent (Arthur et al., 2006). Fit may matter more to individuals with prior work experience across multiple organizations, as they better understand how culture influences success (Kristof-Brown, Jansen, & Colbert, 2002). Moreover, strong relationships with supervisors and coworkers can buffer the effects of misfit, allowing employees to remain engaged even when cultural alignment is low (Erdogan, Kraimer, & Liden, 2004).

Ultimately, the interactionist perspective reminds us that behavior is not solely determined by personality or job design—it’s shaped by the communication climate, leadership style, and organizational norms. A supportive environment can unlock potential in employees who might otherwise be overlooked.

Insider Edge

The Interactionist Perspective—The Role of Fit in Organizational Communication

What’s the Big Idea?

In organizational communication, the Interactionist Perspective flips the script: instead of viewing behavior as solely shaped by the environment or personality, it emphasizes the dynamic interaction between the two. This is where the concept of “fit” becomes a game-changer.

There are two key types of fit:

- Person–Job Fit: Does the individual’s skills, abilities, and interests align with the demands of the job?

- Person–Organization Fit: Does the individual’s values, beliefs, and personality align with the culture and norms of the organization?

When communication flows well, it’s often because these fits are in sync. When it breaks down? Misfit might be the hidden culprit.

Why It Matters in Communication

- Fit shapes tone and style: Someone who thrives in a fast-paced, informal culture may communicate with emojis and Slack shorthand. Someone who values hierarchy and structure may prefer formal emails and clear chains of command.

- Fit influences feedback: Employees who feel aligned with organizational values are more likely to accept and act on feedback. Misaligned employees may resist or misinterpret it.

- Fit affects voice and silence: A strong person–organization fit encourages employees to speak up, share ideas, and challenge norms. Poor fit often leads to disengagement or silence.

Insider Warning: Misfit Is a Communication Risk

Misalignment can lead to:

- Conflict: Differing expectations about communication norms (e.g., direct vs. indirect feedback)

- Misunderstanding: Cultural or value-based disconnects that distort message intent

- Turnover: Employees who feel out of place often leave—not because of the job itself, but because of how communication feels

Your Edge as a Communicator

To leverage the Interactionist Perspective:

- Diagnose fit early: Use onboarding conversations, team assessments, and pulse surveys to gauge alignment.

- Adapt communication styles: Tailor your approach based on individual and cultural fit—not just your own preferences.

- Facilitate cultural bridging: Help team members understand and respect different communication norms rooted in diverse fits.

- Champion inclusive messaging: Create space for voices that may not “fit” the dominant culture but offer valuable perspectives.

Final Takeaway

Fit isn’t just an HR buzzword—it’s a communication lens. When you understand how person–job and person–organization fit shape behavior, you gain the power to decode tensions, build trust, and lead with empathy.

Want to be the communicator everyone trusts? Start by asking: Does this person feel like they belong here—and how does that shape the way they speak, listen, and engage?

Discussion Questions

- How can a company assess person–job fit before hiring employees? What are the methods you think would be helpful?

- How can a company determine person–organization fit before hiring employees? Which methods do you think would be helpful?

- What can organizations do to increase person–job and person–organization fit after they hire employees?

Section 3.3 Individual Differences: Values and Personality

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, you should be able to do the following:

- Define core concepts of values and distinguish between different types of values (e.g., terminal vs. instrumental).

- Analyze the relationship between individual values and workplace behaviors, including decision-making and interpersonal dynamics.

- Classify major personality traits (e.g., Big Five) and evaluate their relevance to organizational behavior.

- Examine how personality traits influence work behaviors and attitudes such as job satisfaction, performance, and organizational commitment.

- Critique the use of personality testing in organizational settings, identifying potential limitations, biases, and ethical concerns.

Individual Differences: Values and Personality

Values

Values are enduring beliefs about what is important in life, guiding how individuals make decisions, interpret their environment, and behave in the workplace. They are shaped by early life experiences, family dynamics, cultural context, and generational influences, and tend to remain relatively stable over time (Rokeach, 1973; Kasser et al., 2002). In organizational settings, values influence everything from job choice and satisfaction to ethical reasoning and interpersonal communication.

Employees are more likely to accept job offers and remain committed to organizations that align with their personal values (Judge & Bretz, 1992; Ravlin & Meglino, 1987). When value congruence is low—especially in environments that fail to support autonomy, fairness, or purpose—turnover and disengagement are more likely (George & Jones, 1996). This makes understanding employee values a strategic priority for leaders and communicators.

One of the most widely used frameworks for assessing values is the Rokeach Value Survey, which categorizes values into:

- Terminal values: Desired end states, such as happiness, freedom, or a prosperous life.

- Instrumental values: Preferred modes of behavior, such as honesty, ambition, or responsibility.

Figure 3.2 Sample Items From Rokeach (1973) Value Survey

| Terminal Values | Instrumental Values |

|---|---|

| A world of beauty An exciting life Family security Inner harmony Self respect |

Broad minded Clean Forgiving Imaginative Obedient |

Rokeach proposed that individuals rank these values hierarchically, revealing which values they prioritize and which they are willing to sacrifice. This ranking helps organizations understand what motivates employees and how to design roles, rewards, and communication strategies that resonate.

Generational shifts also shape value orientations. For example, Generation X (born mid-1960s to early 1980s) tends to be more individualistic and pragmatic, valuing personal growth and work–life balance over traditional career loyalty (Smola & Sutton, 2002). In contrast, Millennials and Gen Z often prioritize purpose-driven work, inclusivity, and mental well-being—values that influence their expectations of leadership and organizational culture.

Understanding values is essential for effective organizational communication. Whether designing internal messaging, managing conflict, or leading change, communicators must recognize that employees interpret messages through the lens of their values. A firefighter may be drawn to risk and action, while a social worker may prioritize empathy and justice. Aligning communication with these value orientations fosters trust, engagement, and ethical behavior.

Personality

Personality refers to the relatively stable patterns of thoughts, emotions, and behaviors that distinguish individuals from one another. In organizational communication, understanding personality helps leaders and teams anticipate how employees may respond to feedback, conflict, collaboration, and change. While personality traits are generally consistent over time, they are not fixed. Life experiences, social roles, and developmental milestones can shape and refine personality across the lifespan (Roberts, Walton, & Viechtbauer, 2006).

For example, individuals often become more emotionally stable, conscientious, and socially dominant between the ages of 20 and 40, while openness to new experiences may gradually decline. These shifts have implications for workplace behavior, leadership development, and team dynamics. Longitudinal studies also show that childhood personality traits—such as self-control or sociability—can predict career satisfaction and success decades later (Judge & Higgins, 1999; Staw, Bell, & Clausen, 1986).

However, personality is only one factor influencing behavior at work. Organizational roles, communication norms, and leadership expectations often shape how individuals express their traits. For instance, an extroverted employee may thrive in a customer-facing role but behave more reservedly in a formal meeting if the culture discourages open dialogue. In environments with greater autonomy and psychological safety, personality tends to exert a stronger influence on behavior (Barrick & Mount, 1993).

Understanding personality through frameworks like the Big Five—which includes openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism—can help organizations design roles, teams, and communication strategies that align with individual strengths. But it’s essential to avoid overgeneralizing or stereotyping. Effective organizational communication recognizes that personality interacts with context, and that behavior is shaped by both internal traits and external expectations.

Big Five Personality Traits

The Big Five Personality Traits—also known as the Five-Factor Model—represent five broad dimensions that help explain individual differences in behavior, communication, and workplace performance. These traits emerged from decades of linguistic and statistical analysis across cultures and languages, revealing consistent patterns in how people describe personality (Goldberg, 1990; APA Dictionary of Psychology, 2023). While not exhaustive, the Big Five offer a foundational framework for understanding how personality influences organizational dynamics.

Figure 3.4 Big Five Personality Traits

| Trait | Description |

|---|---|

|

O

penness |

Being curious, original, intellectual, creative, and open to new ideas. |

|

C

onscientiousness |

Being organized, systematic, punctual, achievement oriented, and dependable. |

|

E

xtraversion |

Being outgoing, talkative, sociable, and enjoying social situations. |

|

A

greeableness |

Being affable, tolerant, sensitive, trusting, kind, and warm. |

|

N

euroticism |

Being anxious, irritable, temperamental, and moody. |

Openness reflects curiosity, creativity, and a willingness to embrace new ideas. Employees high in openness tend to thrive in environments that require adaptability, innovation, and continuous learning. They are more likely to seek feedback, build diverse relationships, and adjust quickly to new roles or organizational cultures (Wanberg & Kammeyer-Mueller, 2000). Open individuals often excel in training, change initiatives, and entrepreneurial ventures (Zhao & Seibert, 2006).

Conscientiousness is the strongest predictor of job performance across industries. It encompasses traits like dependability, organization, and achievement orientation (Barrick & Mount, 1991). Conscientious employees are more likely to meet deadlines, follow safety protocols, and remain committed to long-term goals. They also tend to have lower turnover and absenteeism rates, making them highly valued in recruitment and leadership pipelines (Judge & Ilies, 2002).

Extraversion describes sociability, assertiveness, and enthusiasm for interpersonal interaction. Extraverts often excel in roles involving sales, customer service, and team leadership (Bono & Judge, 2004). Their ability to build rapport and seek feedback supports faster adjustment to new jobs and higher workplace satisfaction (Judge et al., 2002). However, extraverts may struggle in roles that require solitude or minimal social contact, and they may exhibit higher absenteeism due to social obligations (Judge, Martocchio, & Thoresen, 1997).

Agreeableness reflects kindness, empathy, and cooperation. Agreeable employees contribute to team harmony, help others consistently, and are less likely to retaliate during conflict (Ilies, Scott, & Judge, 2006). They may be effective in leadership roles that require fairness and emotional intelligence (Mayer et al., 2007). However, high agreeableness can limit constructive dissent, making individuals less likely to challenge the status quo or initiate change (LePine & Van Dyne, 2001).

Neuroticism involves emotional instability, anxiety, and moodiness. High neuroticism is associated with stress, dissatisfaction, and difficulty forming workplace relationships (Klein et al., 2004). These individuals may report intentions to leave their jobs but often remain due to inertia or fear of change (Judge, Heller, & Mount, 2002). In leadership roles, neuroticism can contribute to perceptions of unfairness and lower team morale (Mayer et al., 2007).

Understanding the Big Five helps organizations design roles, teams, and communication strategies that align with individual strengths. However, personality traits interact with context—meaning that job fit, leadership style, and organizational culture all influence how traits are expressed and perceived.

Myers-Briggs Type Indicator

The Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI) remains one of the most widely recognized personality assessments in organizational settings, especially for team development and communication training. Unlike the Big Five, which measures traits along a continuum, MBTI categorizes individuals into 16 distinct personality types based on four dichotomous dimensions:

- Extraversion (E) vs. Introversion (I)

- Sensing (S) vs. Intuition (N)

- Thinking (T) vs. Feeling (F)

- Judging (J) vs. Perceiving (P)

Each person is classified into a type such as ESTJ or INFP, offering insight into their preferred ways of processing information, making decisions, and interacting with others (Myers & Briggs Foundation, 2023).

Originally developed in the 1940s by Isabel Briggs Myers and Katharine Cook Briggs, MBTI was designed to help World War II veterans identify career paths aligned with their personalities. Today, it is used by millions annually, with over 80% of Fortune 100 companies incorporating MBTI into leadership development, conflict resolution, and team-building programs (Sample, 2004). Its popularity stems from its accessibility and practical application, though it is not intended for employee selection or diagnostic purposes. The Myers & Briggs Foundation explicitly discourages its use in hiring decisions, emphasizing its role in self-awareness and interpersonal understanding.

Despite its widespread use, MBTI has faced criticism from psychologists for its type-based classification, which may oversimplify personality and lack predictive validity for job performance (Pittenger, 2005). However, in organizational communication, MBTI remains a valuable tool for fostering mutual respect, dialogue, and collaboration—especially when used to explore differences in working styles and decision-making preferences.

Figure 3.6 Summary of MBTI Types

| Dimension | Explanation | |

|---|---|---|

| EI | Extraversion: Those who derive their energy from other people and objects. | Introversion: Those who derive their energy from inside. |

| SN | Sensing: Those who rely on their five senses to perceive the external environment. | Intuition: Those who rely on their intuition and huches to perceive the external environment. |

| TF | Thinking: Those who use their logic to arrive at solutions. | Feeling: Those who use their values and ideas about what is right an wrong to arrive at solutions. |

| JP | Judgment: Those who are organized, systematic, and would like to have clarity and closure. | Perception: Those who are curious, open minded, and prefer to have some ambiguity. |

Positive and Negative Affectivity

Affectivity refers to stable individual differences in the tendency to experience positive or negative emotional states. People high in positive affectivity (PA) tend to be cheerful, energetic, and optimistic across situations, while those high in negative affectivity (NA) are more prone to anxiety, irritability, and pessimism—regardless of external circumstances (Watson & Clark, 1984). These traits influence not only personal well-being but also interpersonal dynamics and organizational climate.

In workplace settings, positive affectivity is associated with higher job satisfaction, stronger organizational commitment, and more cooperative behavior (Ilies & Judge, 2003; Vandenberghe et al., 2019). Teams composed of high-PA individuals tend to experience lower absenteeism, greater helping behaviors, and more constructive conflict resolution (George, 1989). Leaders with high PA can foster psychological safety and collaboration, especially when navigating ambiguity or change (Anderson & Thompson, 2004).

Conversely, negative affectivity can dampen team morale and reduce trust. NA is linked to withdrawal behaviors, counterproductive work actions, and lower organizational citizenship (Kaplan et al., 2009). Employees high in NA may perceive greater role conflict and ambiguity, receive less feedback, and struggle with interpersonal relationships—factors that can erode commitment and increase turnover risk (Vantilborgh & Pepermans, 2008).

Importantly, affectivity shapes how individuals interpret communication, respond to feedback, and engage in voice behavior. In supportive environments, PA can amplify engagement and innovation, while NA may moderate reactions to perceived organizational politics or injustice (Bashir, 2021). Recognizing these dispositional tendencies allows organizations to tailor communication strategies, team composition, and leadership approaches to foster a more emotionally intelligent workplace.

Workplace Strategy Pack

Help, I work for a negative supervisor!

Equip yourself with communication strategies, mindset tools, and boundary-setting techniques to effectively manage upward—even when your supervisor is critical, dismissive, or emotionally volatile.

Situation Snapshot

Working under a negative supervisor can feel like walking a tightrope. Whether they’re overly critical, passive-aggressive, micromanaging, or emotionally unpredictable, the impact on morale, productivity, and communication can be profound.

But here’s the truth: you can’t always change your boss—but you can change how you communicate, respond, and protect your professional integrity.

Strategy Toolkit

1. Reframe the Behavior

Instead of labeling your supervisor as “toxic,” try identifying specific behaviors:

- “Frequently interrupts during meetings”

- “Rarely acknowledges contributions”

- “Uses sarcasm or passive aggression”

This helps you respond to patterns, not personalities.

2. Practice Strategic Communication

- Use neutral language: Avoid emotional triggers. Say “I’d like to clarify expectations” instead of “You never tell me what you want.”

- Document interactions: Keep records of key conversations, feedback, and decisions.

- Ask for specifics: If criticism is vague, ask: “Can you give me an example so I can improve?”

3. Set Boundaries Professionally

- Limit emotional exposure: Don’t overshare personal frustrations or seek validation from a negative supervisor.

- Clarify your role: Revisit your job description or goals to stay focused on what’s expected—not what’s emotionally projected.

- Use time buffers: If meetings are draining, schedule short breaks before and after to reset.

4. Build a Support Network

- Find allies: Connect with peers or mentors who can offer perspective and encouragement.

- Seek feedback elsewhere: If your supervisor rarely gives constructive input, ask trusted colleagues for performance insights.

- Use HR wisely: If behavior crosses ethical or professional lines, document and escalate appropriately.

5. Focus on What You Can Control

- Your tone, professionalism, and follow-through

- Your emotional regulation and self-talk

- Your long-term career goals and exit strategy, if needed

Emotional Resilience Tips

| Challenge | Resilience Response |

|---|---|

| Constant criticism | Practice self-affirmation and seek peer feedback |

| Micromanagement | Proactively share updates to reduce anxiety |

| Lack of recognition | Track your wins privately and celebrate with peers |

| Mood swings or volatility | Stay calm, don’t mirror the emotion, and redirect to tasks |

Communication Scripts

- “I want to make sure I’m aligned with your expectations. Could we clarify priorities for this week?”

- “I appreciate the feedback. I’ll focus on [specific action] and follow up by [date].”

- “I’ve noticed some confusion around [issue]. Would it be helpful to set a recurring check-in?”

Final Thought

Working for a negative supervisor doesn’t define your worth—it tests your strategy. With clear communication, emotional boundaries, and a focus on growth, you can navigate the challenge with integrity and emerge stronger.

References

Ashkanasy, N. M., & Daus, C. S. (2005). Rumors of the death of emotional intelligence in organizational behavior are vastly exaggerated. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 26(4), 441–452. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.320

Einarsen, S., Hoel, H., Zapf, D., & Cooper, C. L. (Eds.). (2020). Bullying and harassment in the workplace: Theory, research and practice (3rd ed.). CRC Press.

Goleman, D. (2006). Social intelligence: The new science of human relationships. Bantam Books.

Liu, D., Liao, H., & Loi, R. (2012). The dark side of leadership: A three-level investigation of the cascading effect of abusive supervision on employee creativity. Academy of Management Journal, 55(5), 1187–1212. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2010.0400

Tepper, B. J. (2000). Consequences of abusive supervision. Academy of Management Journal, 43(2), 178–190. https://doi.org/10.2307/1556375

Waldron, V. R. (2012). Communicating emotion at work. Polity Press.

Whetten, D. A., & Cameron, K. S. (2016). Developing management skills (9th ed.). Pearson Education.

Self-Monitoring

Self-monitoring refers to an individual’s ability to observe and regulate their behavior, appearance, and emotional expression in response to social cues (Snyder, 1974; Fuglestad & Snyder, 2009). High self-monitors are often described as “social chameleons”—they adapt their communication style and behavior to fit the expectations of different audiences and contexts. In contrast, low self-monitors tend to behave consistently across situations, guided more by internal states than external feedback.

In organizational settings, high self-monitors often excel in impression management, making them effective in roles that require diplomacy, persuasion, and visibility. They are more likely to be promoted across departments, emerge as informal leaders, and occupy central positions in workplace social networks (Mehra, Kilduff, & Brass, 2001). Their adaptability allows them to navigate complex interpersonal dynamics and build strategic relationships (Turnley & Bolino, 2001).

However, this trait comes with trade-offs. High self-monitors may struggle with authenticity and emotional strain, especially when their outward behavior conflicts with internal feelings. For example, they may project positivity in high-stress situations, which can lead to burnout or emotional fatigue. Additionally, they may avoid giving honest feedback to subordinates to preserve their image or avoid conflict, which can undermine managerial effectiveness (Jawahar, 2001). Research also suggests that high self-monitors may exhibit lower organizational commitment, viewing their current role as a stepping stone rather than a long-term fit (Day et al., 2002).

From an organizational communication perspective, self-monitoring influences how individuals interpret messages, manage impressions, and engage in feedback exchanges. Leaders and communicators should be aware of these dynamics when designing performance evaluations, team-building activities, and leadership development programs.

Proactive Personality

A proactive personality describes an individual’s tendency to take initiative, challenge the status quo, and actively solve problems without waiting for direction. These individuals are often seen as change agents—they anticipate obstacles, seek out opportunities, and drive improvement in their work environments (Crant, 1995). In organizational communication, proactive employees play a critical role in shaping team dynamics, influencing leadership, and fostering innovation.

Proactive individuals tend to be more successful in job searches and career advancement because they navigate organizational politics, build strategic relationships, and adapt quickly to new environments (Brown et al., 2006; Seibert, Kraimer, & Crant, 2001). They are also more likely to engage in voice behavior, offering constructive suggestions and feedback that improve team performance and decision-making. Their eagerness to learn and participate in developmental activities makes them valuable assets in fast-paced or evolving organizations (Major, Turner, & Fletcher, 2006).

However, proactivity is not universally beneficial. In some contexts, proactive individuals may be perceived as overstepping boundaries, especially if their actions conflict with organizational norms or team readiness for change. Research shows that the effectiveness of proactive behavior depends on the individual’s ability to read the environment, align with organizational values, and assess situational demands accurately (Chan, 2006; Erdogan & Bauer, 2005). For example, a proactive employee who pushes for change in a highly hierarchical or risk-averse culture may face resistance or reputational harm.

From a communication standpoint, proactive personalities thrive in environments that support open dialogue, psychological safety, and inclusive leadership. When paired with leaders who encourage initiative and provide clear feedback, proactive employees can amplify organizational learning and adaptability (DuBrin, 2013). Conversely, mismatches in leadership style or cultural fit may suppress their contributions or lead to interpersonal conflict.

Self-Esteem

Self-esteem refers to an individual’s overall evaluation of their self-worth and competence. In workplace settings, self-esteem influences how employees interpret feedback, engage with colleagues, and respond to challenges. Those with high self-esteem tend to be confident, resilient, and more satisfied with their jobs, often demonstrating stronger performance and leadership potential (Judge & Bono, 2001). In contrast, individuals with low self-esteem may experience self-doubt, avoid visibility, and interpret constructive criticism as personal rejection.

Research shows that employees with lower self-esteem are more likely to seek roles in larger, less personalized organizations, where they can remain relatively anonymous (Turban & Keon, 1993). This preference may reflect a desire to avoid scrutiny or interpersonal risk. From a communication standpoint, managing employees with low self-esteem requires empathy, tact, and affirmation. Feedback should be framed constructively, emphasizing growth and strengths to avoid triggering defensiveness or disengagement.

Recent studies also highlight the role of organization-based self-esteem (OBSE)—the extent to which employees feel valued and respected within their organization. OBSE is positively linked to work engagement, psychological safety, and perceived organizational membership, especially when supported by inclusive communication and respectful leadership (Shan, Guang, & Yuling, 2024). Leaders who foster OBSE through recognition, autonomy, and transparent dialogue can enhance both individual well-being and team performance.

Self-Efficacy

Self-efficacy refers to an individual’s belief in their ability to successfully perform a specific task or role. Unlike broad personality traits, self-efficacy is context-specific—someone may feel confident in academic settings but uncertain when tackling mechanical tasks. This belief system plays a powerful role in shaping motivation, goal-setting, and persistence in the workplace (Stajkovic & Luthans, 1998).

Employees with high self-efficacy tend to set ambitious goals, remain committed to achieving them, and recover more quickly from setbacks. These individuals are more likely to engage in proactive behaviors, seek feedback, and contribute to organizational learning (Judge et al., 2007). In contrast, low self-efficacy is associated with avoidance, procrastination, and reduced performance—especially in roles that require autonomy or problem-solving (Steel, 2007; Phillips & Gully, 1997).

Self-efficacy also influences how employees interpret organizational communication. Those with high self-efficacy are more likely to perceive feedback as constructive and empowering, while those with low self-efficacy may interpret the same message as threatening or discouraging. This dynamic affects engagement, trust, and commitment, especially in environments that emphasize continuous improvement and collaboration (Opolot et al., 2024).

Fortunately, self-efficacy can be developed. Organizations can foster it by:

- Hiring and onboarding individuals with demonstrated capabilities

- Providing targeted training and mentoring

- Offering verbal encouragement and recognition

- Creating opportunities for skill mastery and autonomy (Ahearne, Mathieu, & Rapp, 2005)

These strategies not only enhance individual performance but also contribute to a more resilient and adaptable workforce.

Workplace Strategy Pack

Build Your Self-Confidence at Work

To help individuals develop authentic self-confidence through intentional communication, mindset shifts, and strategic workplace behaviors—enhancing performance, visibility, and interpersonal impact.

Why Self-Confidence Matters

Self-confidence isn’t just a personal trait—it’s a communication asset. Confident employees:

- Speak up in meetings

- Advocate for their ideas

- Navigate feedback constructively

- Build trust and credibility with peers and leaders

Low confidence, on the other hand, can lead to self-censorship, missed opportunities, and misinterpretation of competence.

What Self-Confidence Is (and Isn’t)

- It’s not arrogance: True confidence is grounded in self-awareness and humility.

- It’s not perfection: Confidence grows from resilience, not flawlessness.

- It’s not static: It can be built, strengthened, and sustained through practice.

Strategy Toolkit

1. Know Your Strengths

- List 3–5 professional strengths and give examples of when you’ve used them effectively.

- Ask trusted colleagues for feedback on what you do well.

- Keep a “confidence file” of wins, compliments, and successful projects.

2. Communicate with Confidence

- Use assertive language: “I recommend…” instead of “I think maybe…”

- Maintain eye contact and open body posture in meetings.

- Practice speaking up early in group settings to reduce anxiety.

3. Set Achievable Challenges

- Volunteer for tasks slightly outside your comfort zone.

- Break large goals into small wins to build momentum.

- Reflect on progress weekly to reinforce growth.

4. Reframe Negative Self-Talk

- Replace “I’m not good at this” with “I’m learning how to improve.”

- Use cognitive reframing to challenge limiting beliefs.

- Practice self-compassion during setbacks.

5. Build Confidence Through Relationships

- Surround yourself with supportive peers and mentors.

- Offer encouragement to others—it reinforces your own belief in growth.

- Seek feedback as a tool for development, not judgment.

Communication Scripts

- “I’ve researched this approach and believe it could benefit our team—can I walk you through it?”

- “I’m still developing this skill, but I’m committed to improving and open to feedback.”

- “I’d like to take the lead on this project—I believe I can contribute meaningfully.”

Final Takeaway

Confidence isn’t a gift—it’s a skill. When you communicate with clarity, act with intention, and reflect with honesty, you build a foundation of self-trust that transforms how others see you—and how you see yourself.

References

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. W. H. Freeman.

Cameron, K. S., & Whetten, D. A. (2016). Developing management skills (9th ed.). Pearson Education.

Goleman, D. (2006). Social intelligence: The new science of human relationships. Bantam Books.

Robbins, S. P., & Judge, T. A. (2023). Organizational behavior (19th ed.). Pearson Education.

Stajkovic, A. D., & Luthans, F. (1998). Self-efficacy and work-related performance: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 124(2), 240–261. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.124.2.240

Waldron, V. R. (2012). Communicating emotion at work. Polity Press.

Locus of Control

Locus of control refers to an individual’s belief about the extent to which they can influence outcomes in their life. People with a high internal locus of control believe that success or failure stems from their own actions, decisions, and effort. In contrast, those with a high external locus of control attribute outcomes to luck, fate, or external forces such as powerful others or systemic constraints (APA Dictionary of Psychology, 2023).

In workplace settings, internal locus of control is associated with higher motivation, proactive behavior, and stronger job involvement. Internals are more likely to initiate mentor relationships, seek feedback, and take ownership of their development (Ng, Sorensen, & Eby, 2006). They also tend to experience greater psychological well-being, report higher job satisfaction, and demonstrate resilience in the face of setbacks (DeNeve & Cooper, 1998). These traits make internals particularly well-suited for entrepreneurial roles and leadership positions, where autonomy and decision-making are central (Certo & Certo, 2005).

Interestingly, locus of control also influences health outcomes and emotional adjustment. Longitudinal research shows that children with a strong internal locus of control are more likely to adopt healthy habits and experience lower rates of obesity and hypertension later in life (Gale, Batty, & Deary, 2008). Conversely, externals are more prone to stress, depression, and disengagement—especially in environments where they feel powerless or micromanaged (Benassi, Sweeney, & Dufour, 1988).

From an organizational communication perspective, understanding employees’ locus of control can help leaders tailor feedback, delegate responsibilities, and design roles that foster agency and accountability. Internals thrive in cultures that reward initiative and transparency, while externals may benefit from structured support and clear expectations.

Understand Your Locus of Control by Taking a Survey at the Following Web Site:

Personality Testing in Employee Selection

Personality assessments are widely used in employee selection, but their effectiveness and ethical implications remain hotly debated. While personality can influence workplace behavior, it is only one piece of a complex puzzle. Matching individuals to roles based on personality traits may reduce turnover and improve satisfaction, but the predictive power of personality tests for job performance is modest at best—typically explaining only 10–15% of performance variance (Morgeson et al., 2007).

Organizations often use personality tests to assess person–job fit and person–organization fit, aiming to reduce costly mismatches. Tools from companies like Hogan Assessment Systems and Kronos have been credited with lowering on-the-job delinquency and improving retention (Gale, 2002). However, interviews alone are unreliable for detecting key traits like conscientiousness, which is consistently linked to performance across roles (Barrick, Patton, & Haugland, 2000).

Yet, personality testing in high-stakes selection contexts presents challenges:

- Faking and impression management: Applicants may tailor responses to match perceived job requirements, distorting results. While some argue this undermines validity, others suggest faking may reflect adaptive traits like self-monitoring (Tell & Christiansen, 2007).

- Self-report limitations: Individuals may lack insight into their own behavior or provide aspirational answers. Peer and supervisor ratings often offer more accurate assessments (Mount, Barrick, & Strauss, 1994).

- Legal and ethical risks: Tests must comply with anti-discrimination laws. For example, Rent-A-Center faced legal action for using the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory, which included items inappropriate for employment screening and violated the Americans with Disabilities Act (Heller, 2005).

To use personality tests responsibly, organizations should:

- Combine them with cognitive ability tests, structured interviews, and job simulations.

- Validate tests internally by correlating scores with performance data from current employees.

- Ensure tests are job-relevant, non-discriminatory, and aligned with organizational values.

Ultimately, personality testing can support selection decisions when used thoughtfully and in conjunction with other tools. But relying on it exclusively risks overlooking more powerful predictors like cognitive ability and contextual fit.

Discussion Questions

- Reflect on the personality traits discussed in this section, such as conscientiousness, locus of control, self-efficacy, and self-esteem. Identify specific jobs or occupations that align well with each trait. For example, which traits might be ideal for roles in leadership, customer service, or creative industries? Additionally, consider which traits—like conscientiousness—might be universally desirable across all roles and explain why.

- Discuss the unique challenges of managing employees who exhibit low self-efficacy and low self-esteem. How might these traits affect their performance, motivation, and response to feedback? Based on the strategies outlined in this section, propose specific approaches to support and empower these employees, such as providing constructive feedback, verbal encouragement, and opportunities for skill mastery.

- Explore the various methods companies use to assess employee personality, including personality tests, structured interviews, and peer evaluations. Discuss the strengths and limitations of each method, particularly in the context of employee selection. How can organizations ensure these assessments are valid, ethical, and aligned with job requirements?

- Reflect on a personal experience or hypothetical scenario where an individual’s personality did not align with the demands of their job. How did this mismatch affect their attitudes, behaviors, and overall job satisfaction? What steps could be taken to address such mismatches, either by the employee or the organization?

- Consider the potential drawbacks of developing an “ideal employee” profile and using it as a basis for hiring decisions. What risks might arise from focusing too narrowly on specific traits or characteristics? How could this approach inadvertently exclude qualified candidates or lead to a lack of diversity in the workplace? Propose ways to balance the use of profiles with broader, more inclusive hiring practices.

Section 3.4: Perception

Learning Objectives

Type your learning objectives here.

- Analyze how self-concept and identity influence perceptual processes.

- Explain the cognitive mechanisms behind visual perception and evaluate how perceptual tendencies shape behavioral responses.

- Identify common self-perception biases and analyze their impact on interpersonal interactions.

- Compare and contrast biases in perceiving others and assess their implications for social and organizational contexts.

- Evaluate attribution processes and predict their effects on decision-making and behavior in organizational settings.

Section 3.4

Perception

Human behavior in organizations is shaped not only by personality, values, and preferences, but also by how individuals perceive and interpret their environment. Perception is the cognitive process through which people detect, organize, and make sense of environmental stimuli. In organizational communication, perception plays a critical role in how employees interpret messages, evaluate others, and respond to workplace dynamics.

Importantly, perception is not a passive or purely rational process. Individuals engage in selective attention, filtering information based on personal relevance, emotional salience, and cognitive biases (Higgins & Bargh, 1987). For example, a sports enthusiast may immediately notice headlines about their favorite team, while a parent may be drawn to articles on child nutrition. These perceptual filters are influenced by values, needs, fears, and emotions, which shape what individuals notice and how they interpret it (Keltner, Ellsworth, & Edwards, 1993).

Perception can also be distorted by psychological predispositions. In one study, individuals with arachnophobia perceived stationary spiders as moving toward them—demonstrating how fear can override objective reality (Riskin, Moore, & Bowley, 1995). In organizational settings, similar distortions may affect how employees interpret feedback, assess fairness, or respond to leadership. For instance, someone with low self-esteem may perceive neutral feedback as criticism, while someone with high neuroticism may misread workplace ambiguity as personal threat.

Understanding perception is essential for effective organizational communication. Leaders and communicators must recognize that messages are filtered through individual lenses, and that misperceptions can lead to conflict, disengagement, or resistance to change. By fostering psychological safety, encouraging feedback, and clarifying intent, organizations can reduce perceptual bias and promote more accurate understanding.

Visual Perception

Visual perception refers to the process by which individuals interpret and make sense of visual stimuli in their environment. While it may seem objective, perception is often shaped by context, contrast, and cognitive expectations, leading to distortions in how we see and evaluate others (Kellman & Shipley, 1991). For example, when viewing ambiguous shapes, the brain extrapolates missing information—such as perceiving a triangle that isn’t physically present—based on surrounding cues and patterns.

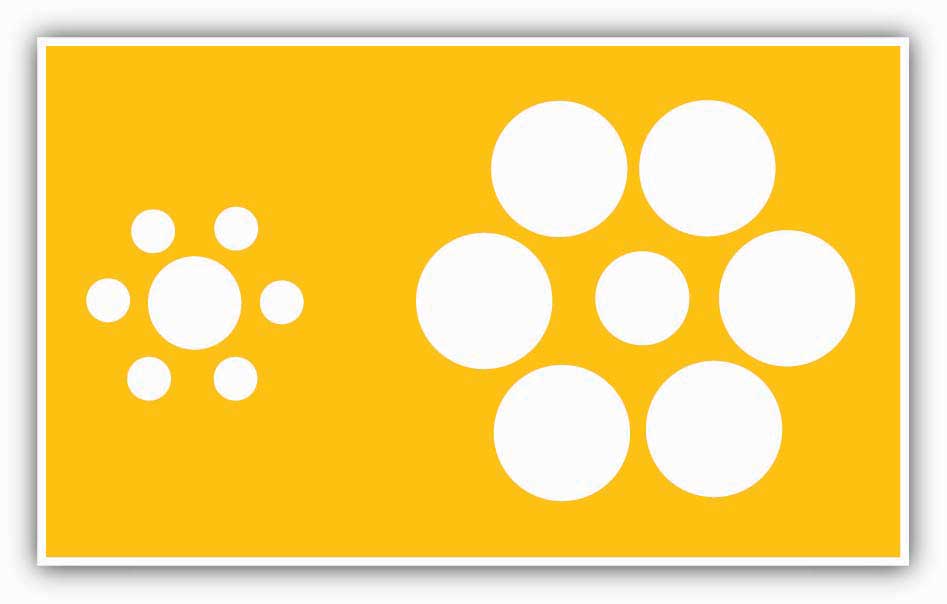

Figure 3.7

Our visual perception goes beyond the information physically available. In this figure, we see the white triangle in the middle even though it is not really there.

Figure 3.8

Which of the circles in the middle is bigger? At first glance, the one on the left may appear bigger, but they are in fact the same size. We compare the middle circle on the left to its surrounding circles, whereas the middle circle on the right is compared to the bigger circles surrounding it.

This principle extends to workplace behavior. Employees are rarely evaluated in isolation; instead, their performance and demeanor are interpreted in contrast to those around them. A team member may appear exceptionally efficient simply because they work alongside slower peers. Similarly, someone perceived as disengaged may be unfairly judged based on selective attention or personal bias—such as assuming a colleague browsing the web is slacking off, when they may be conducting research or completing a task.

These perceptual distortions can lead to misjudgments in performance appraisals, interpersonal conflict, and biased decision-making. In organizational communication, it’s essential to recognize that visual cues are filtered through individual values, emotions, and expectations (Keltner, Ellsworth, & Edwards, 1993). Leaders and teams must strive for evidence-based evaluations, encourage open dialogue, and remain aware of how visual perception can skew interpretation of behavior.

Recent research also highlights how object space and visual similarity influence perception. For instance, individuals who struggle with face discrimination may also misinterpret other objects with similar visual attributes, suggesting that perceptual biases are not just situational but also tied to individual differences in cognition (Sigurdardottir & Ólafsdóttir, 2025).

Self-Perception

Self-perception refers to how individuals evaluate and interpret their own traits, behaviors, and capabilities. While self-awareness is essential for personal growth and workplace effectiveness, human beings are prone to systematic biases in how they perceive themselves—often shaped by personality, emotional state, and social context.

One common bias is self-enhancement, the tendency to overestimate one’s abilities and view oneself more positively than others do. Individuals with narcissistic traits are especially susceptible, but even those without clinical narcissism may inflate their competence or contributions (John & Robins, 1994). In organizational settings, this bias can lead to misaligned expectations, frustration over lack of recognition, and resistance to feedback.

On the opposite end is self-effacement, where individuals undervalue their performance and interpret events in ways that diminish their self-worth. This bias is often linked to low self-esteem and can result in excessive self-blame, reduced confidence, and missed opportunities for advancement. Employees who consistently downplay their strengths may be overlooked for promotions or fail to advocate for themselves in team settings.

Another pervasive bias is the false consensus effect—the tendency to overestimate how common one’s behaviors or beliefs are among others (Ross, Greene, & House, 1977). For example, an employee who takes office supplies home or exaggerates accomplishments may assume such actions are widespread and socially acceptable. This perception can normalize unethical behavior, especially in environments lacking clear communication about values and expectations (Fields & Schuman, 1976).

From an organizational communication perspective, these biases affect how employees receive feedback, interpret norms, and engage in ethical decision-making. Leaders and communicators must foster environments that encourage self-reflection, psychological safety, and honest dialogue, helping individuals calibrate their self-perceptions and align with organizational values.

Social Perception

Social perception refers to how individuals interpret and evaluate others in their environment. In organizational settings, this process is shaped by personal values, emotions, and personality traits—and it directly influences how we communicate, collaborate, and make decisions. Importantly, our perceptions of others are not neutral; they are filtered through cognitive shortcuts and biases that can reinforce stereotypes and shape behavior in ways that are self-reinforcing.

One of the most pervasive biases in social perception is stereotyping—the tendency to generalize characteristics based on group membership. While categorization helps us make sense of complex environments, it becomes problematic when we apply group-level assumptions to individuals. For example, assuming that men are more assertive than women may lead to biased hiring decisions, even when female candidates are equally or more qualified. These biases can result in discrimination, miscommunication, and missed opportunities for inclusion (Snyder, Tanke, & Berscheid, 1977).

Stereotypes often trigger self-fulfilling prophecies, where expectations shape behavior in ways that confirm the original belief. If a manager assumes that young employees are disengaged, they may withhold meaningful assignments—leading to boredom and underperformance that reinforces the stereotype. Conversely, positive stereotypes may elicit warmth and cooperation, but still obscure individual differences and reduce authenticity in relationships.

Another key mechanism is selective perception—the tendency to notice information that aligns with our beliefs while ignoring contradictory evidence. This bias was famously illustrated in a 2007 social experiment where violinist Joshua Bell performed incognito in a Washington, D.C. metro station. Despite his global acclaim and a $3.5 million instrument, most commuters failed to recognize the quality of his performance, earning him just $32 in tips (Weingarten, 2007). The context shaped perception more than the objective stimulus.

In organizations, selective perception can influence how leaders interpret market signals, employee behavior, or feedback. Executives with marketing backgrounds may focus on customer trends, while those in IT may prioritize technological shifts (Waller, Huber, & Glick, 1995). These perceptual filters can reinforce functional silos and limit strategic agility.

Even when individuals encounter information that contradicts their beliefs, they may resist updating their perceptions. This resistance can take the form of subcategorization (e.g., labeling assertive women as “career women” to preserve gender stereotypes) or discounting contradictory evidence as flawed or irrelevant (Lord, Ross, & Lepper, 1979). These tendencies make it difficult to challenge entrenched biases—even with compelling data.

Finally, first impressions exert a powerful influence on workplace relationships. Once formed, they tend to persist—even when new information contradicts the initial judgment. This is because impressions become psychologically independent of the evidence that created them (Ross, Lepper, & Hubbard, 1975). For example, if a colleague appears rude during a stressful moment, that impression may stick, even after learning about their personal challenges. Being aware of this bias and remaining open to new information can help mitigate its impact.

Workplace Strategy Pack

Navigating Subjectivity at Work

Objective

To help employees recognize how personal experiences, values, and biases shape perception—and to develop strategies for more mindful, inclusive, and effective communication in diverse organizational settings.

Why It Matters

In the workplace, perception is not objective—it’s filtered through lenses like culture, upbringing, emotions, and assumptions. These filters influence how people interpret tone, intent, and behavior. Miscommunication often stems from treating assumptions as facts or believing our view is the only “truth.”

Understanding subjectivity helps:

- Reduce conflict and defensiveness

- Improve empathy and listening

- Foster inclusive decision-making

- Build trust across diverse teams

Organizational “truth” is often negotiated—not absolute. Recognizing this allows teams to co-create meaning rather than impose it.

Strategy Toolkit

1. Recognize Your Filters

Encourage employees to reflect on:

- Cultural norms (e.g., direct vs. indirect communication)

- Emotional states (e.g., stress, fatigue)

- Personal values (e.g., independence, loyalty)

- Past experiences (e.g., authority figures, feedback styles)

Use journaling or team exercises to explore how these influence perception.

2. Pause Assumptions

Teach the difference between:

- Observation: “She didn’t respond to my message.”

- Assumption: “She’s ignoring me.” Encourage teams to ask clarifying questions before reacting.

3. Practice Perspective-Taking

Use role-play or storytelling to explore how others might interpret the same situation differently. Normalize multiple truths and shared meaning-making.

4. Facilitate Meaningful Dialogue

Create spaces for open conversation:

- Use structured dialogue formats (e.g., circle discussions, feedback protocols)

- Encourage curiosity over certainty

- Validate differing viewpoints without forcing agreement

5. Train in Cultural and Emotional Intelligence

Offer workshops on:

- Bias awareness

- Active listening

- Conflict resolution

- Intercultural communication

Empowerment Tip

Subjectivity isn’t a flaw—it’s a feature of being human. The goal isn’t to eliminate bias, but to become aware of it. When you pause to question your assumptions, you open the door to deeper understanding and stronger collaboration.

References

Brummans, B. H. J. M., Taylor, B. C., & Sivunen, A. (Eds.). (2024). The Sage handbook of qualitative research in organizational communication. SAGE Publications. https://us.sagepub.com/en-us/nam/the-sage-handbook-of-qualitative-research-in-organizational-communication/book280914

Dutta, A., Steiner, E., Proulx, J., Berisha, V., Bliss, D. W., Poole, S., & Corman, S. (2021). Analyzing the relationship between productivity and human communication in an organizational setting. PLOS ONE, 16(7), e0250301. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0250301

Oklahoma State University. (n.d.). 1.5 Approaches to organizational communication research. In Organizational Communication. https://open.library.okstate.edu/orgcomm/chapter/1-5-approaches-to-organizational-communication-research/

Attributions

In organizational communication, how we interpret others’ behavior—especially in moments of success or failure—shapes our own responses and decisions. This process is known as attribution, or the causal explanation we assign to observed behavior. Whether we believe someone missed a deadline due to laziness or due to an unreasonable workload influences whether we offer help, extend empathy, or assign blame.

Attributions fall into two broad categories:

- Internal attributions: Behavior is explained by personal traits or dispositions (e.g., “Peter is irresponsible”).

- External attributions: Behavior is explained by situational factors (e.g., “The project was unusually complex”).

According to Kelley’s (1967, 1973) covariation model, we consider three factors when making attributions:

- Consensus: Do others behave similarly in the same situation?

- Distinctiveness: Does the person behave differently in other contexts?

- Consistency: Does the person behave this way repeatedly in the same context?

For example, if Erin complains about a finance assignment and others do too (high consensus), she rarely complains in other classes (high distinctiveness), and this is a one-time event (low consistency), we’re likely to make an external attribution—the assignment was unusually difficult. But if Erin is the only one complaining (low consensus), does so across contexts (low distinctiveness), and consistently complains in finance (high consistency), we’re more likely to make an internal attribution—Erin is a negative person.

However, attribution is not always objective. Relationship dynamics influence how we interpret behavior. Managers who favor certain employees may attribute their successes to internal traits and their failures to external circumstances (Heneman, Greenberger, & Anonyou, 1989). Additionally, individuals often exhibit self-serving bias, attributing their own successes to internal factors and failures to external ones (Malle, 2006).

These attribution patterns have real consequences:

- Internal attributions for failure often lead to punishment or criticism.

- External attributions for failure may prompt support or empathy.

- Internal attributions for success increase the likelihood of recognition and reward.

- External attributions for success may diminish perceived merit.

Understanding attribution processes helps leaders and communicators respond more fairly and effectively, fostering trust, psychological safety, and ethical decision-making in the workplace.

Table 3.1 Consensus, distinctiveness, and consistency determine the type of attribution we make in a given situation.

| Consensus | Distinctiveness | Consistency | Type of attribution |

|---|---|---|---|

| High consensus | High distinctiveness | Low consistency | External |

| Everyone else behaves the same way. | This person does not usually behave this way in different situations. | This person does not usually behave this way in this situation. | |

| Low consensus | Low distinctiveness | High consistency | Internal |

| No one else behaves the same way. | This person usually behaves this way in different situations. | Every time this person is in this situation, he or she acts the same way. |

Discussion Questions

- What are the implications of contrast error for interpersonal interactions in the workplace? Does this error occur only when observing physical objects, or have you encountered it when perceiving the behavior of others? Provide examples from your own experiences. How can awareness of contrast error improve fairness in evaluations and decision-making?

- What are the problems associated with false consensus error in organizational settings? How might this bias affect ethical decision-making and team dynamics? As a manager, what strategies would you use to minimize the impact of false consensus error on your leadership and communication?

- Is there such a thing as a “good” stereotype? Can positive stereotypes be useful in certain situations, or are they still problematic? Reflect on how even “good” stereotypes might limit authentic relationships or perpetuate biases in hiring, promotions, or team assignments.

- How can organizations address the fact that human beings naturally develop stereotypes? What steps would you take to prevent stereotypes from creating unfairness in hiring, performance evaluations, or promotions? Discuss how selective perception and subcategorization might perpetuate stereotypes, even when contradictory evidence is present.

- Is it possible to influence the attributions others make about your behavior? Imagine you’ve successfully completed a project. What actions or communication strategies would you use to ensure your manager makes an internal attribution (e.g., attributing success to your skills and effort)? Conversely, if you fail at a task, how might you frame the situation to encourage an external attribution (e.g., attributing failure to situational factors)?

Section 3.5: The Role of Ethics and National Culture

Individual Differences and Ethics

Ethical behavior in organizations is shaped not only by situational factors and company culture, but also by individual differences—including personality traits, values, and perceptual biases. While organizational systems such as rewards, punishments, and ethical codes play a critical role, research shows that personal dispositions significantly influence how employees interpret and respond to ethical dilemmas.

For example, individuals with an economic value orientation—those who prioritize wealth and material gain—are more likely to engage in unethical behavior, especially when ethical choices conflict with personal gain (Hegarty & Sims, 1978, 1979). Similarly, employees with an external locus of control, who believe outcomes are shaped by external forces rather than personal actions, tend to deflect responsibility and are more prone to unethical decisions (Trevino & Youngblood, 1990).

Perceptual biases also affect ethical behavior. The self-enhancement bias—our tendency to overestimate our own ethicality—can lead to complacency and resistance to feedback. Individuals often rate themselves as more ethical than others perceive them to be, which reduces motivation to improve and may blind them to the impact of their actions. This disconnect underscores the importance of feedback and perspective-taking in ethical development.

Attribution processes further shape how we respond to others’ unethical behavior. If we attribute misconduct to internal traits (e.g., “they’re dishonest”), we’re more likely to punish the individual. If we attribute it to external circumstances (e.g., “they were under pressure”), we may respond with empathy or corrective support. In a study examining reactions to workplace sexual harassment, participants who attributed responsibility to the victim were significantly less likely to punish the harasser—highlighting how attribution biases can perpetuate injustice (Pierce et al., 2004).

From an organizational communication perspective, these findings emphasize the need for ethical dialogue, reflective practices, and inclusive feedback systems. Encouraging employees to examine their values, challenge biases, and consider multiple perspectives can foster a more ethical and empathetic workplace culture.

Individual Differences Around the Globe

Understanding how personality, values, and perception vary across cultures is essential for effective organizational communication and global leadership. While individuals differ within every nation, national culture reflects dominant value systems that shape workplace behavior, motivation, and communication preferences.

One of the most influential frameworks for comparing cultures is Hofstede’s cultural dimensions theory, which identifies four key dimensions:

- Individualism vs. Collectivism: The degree to which people prioritize personal goals over group goals.

- Power Distance: The extent to which inequality and hierarchy are accepted.

- Uncertainty Avoidance: The level of comfort with ambiguity and change.

- Masculinity vs. Femininity: The emphasis on achievement and competition versus care and cooperation (Hofstede, 2001).

These dimensions help explain why management practices that succeed in one country may falter in another. For example, participative leadership may thrive in low power distance cultures but face resistance in hierarchical societies.

Research also shows that personality traits are broadly universal, with the Five-Factor Model (openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism) validated across more than 79 countries (McCrae & Costa, 1997). However, the dominant traits vary by region. Western cultures tend to score higher on extraversion, while collectivist cultures may emphasize emotional restraint and social harmony. Historical factors such as exposure to infectious diseases have shaped these patterns—regions with higher disease prevalence often exhibit lower openness and extraversion, likely due to social avoidance and strict behavioral norms (Schaller & Murray, 2008).

Perception also differs across cultures. Westerners often focus on individual attributes, while East Asians are more attuned to contextual cues. In one study, Japanese participants considered the emotions of surrounding individuals when interpreting a person’s facial expression, whereas Americans focused solely on the target face (Masuda et al., 2008). These differences affect how messages are interpreted and how relationships are formed in multicultural teams.

Even perceptual biases like self-enhancement are culturally shaped. Western individuals may overestimate traits like independence and assertiveness, while those in collectivist cultures may exaggerate their loyalty and cooperativeness—traits more socially valued in their context (Sedikides et al., 2003; Sedikides et al., 2005).

Recognizing these global variations in individual differences allows communicators and managers to adapt their strategies, foster inclusion, and build trust across cultural boundaries.

Personality Around the Globe

Which countries report the highest and lowest levels of self-esteem among their populations?

Researchers have explored this by surveying thousands of individuals across dozens of nations using tools like the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale. While earlier studies (e.g., Schmitt & Allik, 2005) highlighted countries like Serbia and Chile as leaders in self-reported self-esteem, more recent data show shifts in global confidence levels.

Top Nations for Self-Reported Self-Esteem (2025)

Based on updated global surveys, the countries with the highest average self-esteem include:

- Australia

- Denmark

- United States

- Mexico

- Turkey

- Ukraine

- Brazil

- Argentina

- Canada

- Germany

These nations tend to score higher on self-love indexes and report greater satisfaction with personal appearance, autonomy, and emotional well-being

Nations with Lower Self-Reported Self-Esteem

Countries with lower average self-esteem scores include:

- Saudi Arabia

- South Korea

- France

- Japan

- Hong Kong

- Bangladesh

- Taiwan

- Czech Republic

- Switzerland

- Italy

These rankings reflect cultural norms around modesty, collectivism, and emotional expression, which may influence how individuals report self-worth

References

Schmitt, D. P., & Allik, J. (2005). The simultaneous administration of the Rosenberg self-esteem scale in 53 nations: Culture-specific features of global self-esteem. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 89(4), 623–642. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.89.4.623

Soocial Team. (2025). 20 self-esteem statistics that will help you feel better. https://www.soocial.com/self-esteem-statistics/

Perera, K. (n.d.). Global self-esteem: The most confident countries in the world. MoreSelfEsteem.com.. https://more-selfesteem.com/self-esteem-around-the-world/

U.S. News & World Report. (2022, November 29). Survey: The most self-assured countries. https://www.usnews.com/news/best-countries/articles/2022-11-29/survey-the-most-self-assured-countries

Discussion Questions

- If ethical decision-making is influenced by personality traits, what strategies can organizations implement to encourage ethical behavior among employees? Consider how hiring practices, training programs, and organizational culture can address individual differences in values and locus of control. How might feedback systems and self-awareness initiatives help employees overcome perceptual biases like self-enhancement?

- Do you think personality tests developed in Western cultures are suitable for employee selection in other cultural contexts? Reflect on how cultural differences in dominant personality traits (e.g., extraversion vs. introversion) and values (e.g., individualism vs. collectivism) might affect the validity of these tests. What adjustments or considerations should organizations make when using personality assessments globally?

Section 3.6: Spotlight

Smart Hiring, Stronger Teams in St. Louis: How TCARE and SteadyMD Reduce Turnover Through Strategic Fit

Figure 3.10

Replacing employees is costly—not just in dollars, but in lost productivity, morale, and institutional knowledge. According to the Society for Human Resource Management (SHRM), the average cost to replace an employee can range from 50% to 200% of their annual salary, depending on the role (SHRM, 2022). For fast-growing companies like TCARE Inc. and SteadyMD, minimizing turnover is not just a financial imperative—it’s a strategic one. Both organizations have embraced data-driven hiring practices to ensure better alignment between candidates and roles, ultimately boosting retention and performance.

TCARE Inc., a health tech company focused on caregiver support and aging-in-place solutions, has applied its own behavioral analytics platform to workforce management. Originally designed to reduce caregiver burnout, TCARE’s tools now help match employees to roles based on emotional resilience, communication style, and long-term compatibility. By integrating behavioral data into the hiring process, TCARE improves person-job fit—ensuring that employees are not only capable of performing their duties but are also emotionally equipped to thrive in high-stress environments (TCARE, 2024).

SteadyMD, a telehealth company operating in all 50 states, takes a similarly intentional approach. The company uses structured interviews, inclusive language in job postings, and values-based screening to ensure person-organization fit. Their hiring process emphasizes flexibility, collaboration, and mission alignment—qualities that are essential in a remote-first, fast-paced healthcare startup (SteadyMD, 2024). By focusing on shared values and communication preferences, SteadyMD reduces the risk of cultural mismatch, which is a common cause of early turnover in startups.

Both companies also invest in onboarding and feedback systems that reinforce alignment after hiring. TCARE’s centralized HR systems and SteadyMD’s virtual town halls, DEI events, and peer recognition channels help new hires feel connected and supported. These practices not only improve retention but also foster high performance by creating psychologically safe environments where employees can grow and contribute meaningfully.

Ultimately, the success of TCARE and SteadyMD demonstrates that hiring for fit—both with the job and the organization—is not just a “nice to have.” It’s a business-critical strategy. By leveraging behavioral insights, inclusive practices, and structured onboarding, these companies have built resilient teams that are more engaged, more productive, and more likely to stay.

References

SHRM. (2022). The real cost of employee turnover. Society for Human Resource Management. https://www.shrm.org/

SteadyMD. (2024). Corporate careers and culture. https://www.steadymd.com/careers/

TCARE. (2024). Caregiver support and workforce solutions. https://www.tcare.ai/

Discussion Questions

- Why is it so expensive for companies to replace workers?

- In modern times it is possible that an employee could have a number of different jobs in a short amount of time. Do you think this frequent job changing could skew results for this type of “ideal” employee selection? Do you think potential candidates can use these screening mechanisms to their advantage by making themselves seem like perfect candidates when in fact they are not?

- What personality traits may not seem like a good fit based on an initial screening but in fact would make a good employee?

- Do you feel that hard work and dedication could overcome a person-job mismatch?

Section 3.7: Conclusion