Chapter 4: Individual Attitudes and Behaviors

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, you should be able to do the following:

- Classify major work attitudes (e.g., job satisfaction, organizational commitment) and analyze how they influence workplace behavior and decision-making.

- Evaluate key employee behaviors (e.g., performance, citizenship, absenteeism) and their impact on organizational effectiveness.

- Examine the relationship between work attitudes and ethical decision-making in organizational contexts.

- Compare and contrast cross-cultural differences in job attitudes and workplace behaviors and assess their implications for global organizational communication.

Section 4.1: Spotlight

A Culture of Excellence: How Washington University in St. Louis Fosters Positive Work Attitudes and Ethical Behavior

Washington University in St. Louis (WashU) has earned a reputation as one of the best places to work in the region, and for good reason. The university’s commitment to employee well-being, professional development, and ethical leadership creates a workplace culture that supports both individual fulfillment and organizational performance. These efforts are not merely perks—they are strategic investments that shape employee attitudes and behaviors in ways that align with WashU’s mission of excellence in education, research, and service.

One of the most influential factors in shaping positive work attitudes at WashU is its comprehensive benefits package. Employees have access to tuition assistance, mental health services, generous retirement plans, and flexible scheduling options. These offerings contribute to job satisfaction and organizational commitment—two key predictors of employee engagement and retention (Robbins & Judge, 2022). When employees feel supported in both their personal and professional lives, they are more likely to exhibit organizational citizenship behaviors such as collaboration, initiative, and loyalty.

WashU also places a strong emphasis on professional growth through initiatives like the Institute for Leadership Excellence. This program provides staff with leadership training and career development opportunities, reinforcing a growth mindset and encouraging continuous learning. According to Locke and Latham’s goal-setting theory, employees who are given clear, attainable goals and the tools to achieve them are more motivated and productive (Locke & Latham, 2002). WashU’s investment in internal talent development ensures that employees are not only competent but also confident in their roles.

Ethical behavior is another cornerstone of WashU’s workplace culture. The university’s Code of Conduct and Standards of Conduct Policy outline expectations for integrity, accountability, and respect. These documents serve as both a moral compass and a practical guide for decision-making, helping employees navigate complex situations with clarity and confidence. Ethical climates like WashU’s reduce the likelihood of misconduct and foster trust among colleagues, which is essential for effective teamwork and leadership (Treviño et al., 2006).

Moreover, WashU’s alignment between organizational values and employee expectations enhances person–organization fit. The university’s focus on inclusion, service, and lifelong learning attracts individuals whose personal values mirror those of the institution. This alignment strengthens affective commitment and reduces turnover, particularly in mission-driven sectors like higher education and healthcare. Employees who feel that their work has meaning are more likely to stay engaged and contribute to long-term success.

In sum, Washington University in St. Louis exemplifies how thoughtful organizational practices can shape work attitudes, ethical behavior, and performance. By fostering a culture of support, growth, and integrity, WashU not only attracts top talent but also empowers its people to thrive—making it a model for institutions seeking to align employee well-being with organizational excellence.

References

Locke, E. A., & Latham, G. P. (2002). Building a practically useful theory of goal setting and task motivation. American Psychologist, 57(9), 705–717. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.57.9.705

Robbins, S. P., & Judge, T. A. (2022). Organizational behavior (19th ed.). Pearson.

Treviño, L. K., Weaver, G. R., & Reynolds, S. J. (2006). Behavioral ethics in organizations: A review. Journal of Management, 32(6), 951–990. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206306294258

Washington University in St. Louis. (2024). Code of Conduct. https://universitycompliance.wustl.edu/code-of-conduct/

Washington University in St. Louis. (2024). Standards of Conduct Policy. https://hr.wustl.edu/items/standards-of-conduct-policy/

Discussion Questions

- How can transparent and inclusive communication from leadership influence employees’ long-term commitment to an organization, especially during periods of change or uncertainty?

- In what ways do internal communication channels—such as team meetings, performance feedback, or recognition platforms—shape how valued and supported employees feel in their roles?

- What role does two-way communication play in understanding employee needs and tailoring professional development programs that genuinely enhance retention and job satisfaction?

- How can an organization’s storytelling—about its mission, culture, or employee success—be used to foster a deeper sense of belonging and pride that reduces turnover?

Section 4.2: Work Attitudes

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, you should be able to:

- Define the concept of work attitudes and illustrate their role in organizational settings.

- Explain the relationship between attitudes and behaviors, and demonstrate how one influences the other in workplace contexts.

- Differentiate between job satisfaction and organizational commitment by comparing their definitions, components, and implications.

- Identify and categorize the key factors that contribute to job satisfaction and organizational commitment.

- Describe the potential consequences of job satisfaction and organizational commitment on employee performance and organizational outcomes.

- Evaluate methods companies use to track work attitudes and recommend strategies for improving measurement accuracy and relevance.

Our behavior at work is often shaped by how we feel about being there. Understanding employee behavior requires insight into their work attitudes—the opinions, beliefs, and emotional responses individuals hold toward aspects of their environment. Just as we form attitudes toward food, people, or courses, we also develop attitudes toward our jobs and organizations.

Two work attitudes are especially influential:

- Job Satisfaction: The degree to which individuals feel positively about their job. It encompasses satisfaction with tasks, relationships, compensation, and work-life balance. Job satisfaction is one of the most studied constructs in organizational psychology and is consistently linked to performance, retention, and well-being (Kammeyer-Mueller, Rubenstein, & Barnes, 2024).

- Organizational Commitment: The emotional attachment and loyalty an employee feels toward their organization. Commitment reflects a desire to remain with the company and contribute to its success. While distinct from job satisfaction, the two often overlap—employees who enjoy their work are more likely to feel committed to their employer.

Recent surveys underscore the importance of these attitudes. A 2022 Gallup poll found that 88% of U.S. employees reported being at least somewhat satisfied with their jobs. A 2023 Pew Research Center study revealed that 51% of workers were extremely or very satisfied, especially with aspects like relationships, commute, and daily tasks (Horowitz & Parker, 2023).

The Attitude–Behavior Link

How strongly do attitudes predict behavior? The answer depends on several factors:

- Type of Attitude: Attitudes toward coworkers may influence helping behavior, while attitudes toward the job may better predict turnover intentions.

- Intentions vs. Actions: Attitudes are more closely tied to behavioral intentions than to actual behavior. For example, dissatisfaction may lead someone to consider quitting, but whether they actually leave depends on external factors like job market conditions, financial constraints, and family obligations.

- Situational Constraints: Even strong attitudes may not result in action if the environment limits options. This highlights the importance of considering both internal dispositions and external circumstances when predicting workplace behavior.

The theory of reasoned goal pursuit suggests that attitudes influence behavior through a dynamic process involving intentions, goals, social context, and perceived control (Ajzen & Kruglanski, 2019). Organizations that understand this process can better anticipate employee actions and design interventions that support positive attitudes and ethical behavior.

Workplace Strategy Pack

Empowering Employees to Cultivate Happiness at Work

This strategy pack provides actionable guidance for employees to enhance their own happiness in the workplace by leveraging principles of organizational communication. It draws on recent research to highlight how communication, mindset, and proactive engagement contribute to well-being and satisfaction at work.

Key Insights

- Effective Communication Boosts Happiness

- Open, transparent, and bi-directional communication between employees and management fosters trust, belonging, and job satisfaction.

- Employees who feel heard and valued report higher levels of happiness and engagement (Proctor, 2014).

- Internal Communication as a Happiness Driver

- Internal communication strategies that include feedback, recognition, and peer interaction are linked to increased well-being and reduced burnout.

- Happiness Management frameworks emphasize emotional experience and positive personality development through communication (Romero-Rodríguez & Castillo-Abdul, 2024).

- Positive Work Culture Enhances Resilience

- A culture of appreciation and psychological safety encourages employees to express concerns, share ideas, and build meaningful relationships.

- Happy employees are more optimistic, collaborative, and productive (Kumari & Khatri, 2023).

Employee Strategies for Cultivating Workplace Happiness

| Strategy | Description | Communication Tip |

|---|---|---|

| Self-Reflection | Regularly assess your emotional state and job satisfaction. | Journal or share feedback with a trusted colleague or mentor. |

| Seek Feedback | Ask for constructive input to grow and feel valued. | Use open-ended questions in one-on-one meetings. |

| Express Appreciation | Acknowledge others’ contributions to build positivity. | Send a quick thank-you message or shout-out in team meetings. |

| Engage in Dialogue | Participate in team discussions and decision-making. | Practice active listening and assertive speaking. |

| Build Relationships | Foster connections with peers across departments. | Initiate informal chats or join cross-functional projects. |

| Use Communication Channels Wisely | Leverage platforms like Slack, Teams, or email to stay informed and connected. | Be clear, respectful, and timely in your messages. |

Organizational Support Mechanisms

- Feedback Systems: Regular surveys and pulse checks to monitor employee sentiment.

- Recognition Programs: Celebrating achievements and milestones.

- Transparent Leadership: Leaders modeling open communication and vulnerability.

- Training & Development: Workshops on emotional intelligence, communication skills, and resilience.

References

Kumari, P., & Khatri, P. (2023). Happiness at work from communication lens: A review and research agenda. Journal of Content, Community & Communication, 18, 1–12. https://www.amity.edu/gurugram/jccc/pdf/8Sep-23.pdf

Proctor, C. (2014). Effective organizational communication affects employee attitude, happiness, and job satisfaction (Master’s thesis, Southern Utah University). https://www.suu.edu/hss/comm/masters/capstone/thesis/proctor-c.pdf

Romero-Rodríguez, L. M., & Castillo-Abdul, B. (2024). Internal communication from a happiness management perspective: State-of-the-art and theoretical construction of a guide for its development. BMC Psychology, 12, Article 644. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1186/s40359-024-02140-7

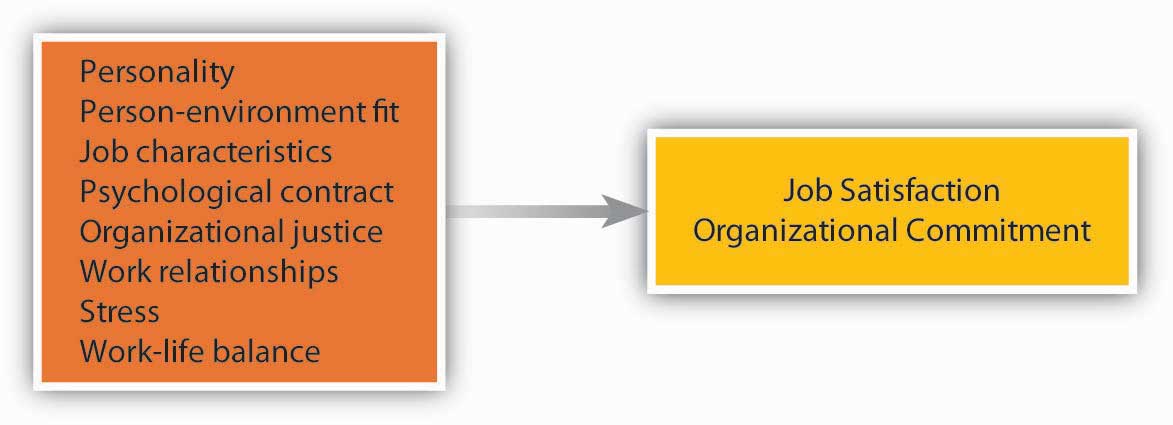

What Causes Positive Work Attitudes?

Employees develop job satisfaction and organizational commitment based on how they experience their work environment. While personality and values play a role, research consistently shows that situational factors—such as relationships, fairness, and job design—are key drivers of positive work attitudes (Kammeyer-Mueller et al., 2024).

Personality

Can assessing the work environment fully explain how satisfied we are on the job? Interestingly, some experts have shown that job satisfaction is not purely environmental and is partially due to our personality. Some people have a disposition to be happy in life and at work regardless of environmental factors.

It seems that people who have a positive affective disposition (those who have a tendency to experience positive moods more often than negative moods) tend to be more satisfied with their jobs and more committed to their companies, while those who have a negative disposition tend to be less satisfied and less committed (Connolly & Viswesvaran, 2000; Thoresen et al., 2003). This is not surprising, as people who are determined to see the glass as half full will notice the good things in their work environment, while those with the opposite character will find more things to complain about. In addition to our affective disposition, people who have a neurotic personality (those who are moody, temperamental, critical of themselves and others) are less satisfied with their job, while those who are emotionally more stable tend to be more satisfied. Other traits such as conscientiousness, self-esteem, locus of control, and extraversion are also related to positive work attitudes (Judge et al., 2002; Judge & Bono, 2001; Zimmerman, 2008). Either these people are more successful in finding jobs and companies that will make them happy and build better relationships at work, which would increase their satisfaction and commitment, or they simply see their environment as more positive—whichever the case, it seems that personality is related to work attitudes. While personality sets the tone for how we interpret our environment, job satisfaction and commitment are shaped through ongoing interactions with workplace conditions. The following factors illustrate how situational elements contribute to—and interact with—individual dispositions.

Person–Environment Fit

In fact, one reason personality matters is that it influences how well we align—or ‘fit’—with our organizational setting. P–E fit refers to the degree of alignment between an individual’s values, personality, and goals and those of the organization or role. When employees feel they “belong” in their company’s culture or job, they tend to:

- Experience higher job satisfaction and organizational commitment

- Report greater engagement and lower turnover intentions

- Perform better and collaborate more effectively (Kristof-Brown et al., 2005)

It includes different types of fit, such as person–job fit, person–organization fit, and even person–supervisor fit—all of which predict positive attitudes and outcomes.

Job Characteristics

Jobs that offer variety, autonomy, feedback, and task significance tend to foster satisfaction and commitment. These features allow employees to use their skills meaningfully and feel a sense of purpose. However, their impact depends on individual differences—employees with a high need for growth benefit most from enriched job designs (Loher et al., 1985; Mathieu & Zajac, 1990).

Organizational Justice & Psychological Contract

Perceptions of fairness—in policies, compensation, and interpersonal treatment—strongly influence work attitudes. Organizational justice includes:

- Procedural justice: fairness in decision-making processes

- Distributive justice: fairness in outcomes like pay and promotions

- Interactional justice: respectful and transparent communication

Employees also form a psychological contract—an informal belief about what they owe the organization and what they expect in return. When this contract is violated (e.g., layoffs despite strong performance), satisfaction and commitment decline (Cohen-Charash & Spector, 2001; Meyer et al., 2002).

Relationships at Work

Positive relationships with coworkers and managers are among the strongest predictors of job satisfaction. Feeling respected, socially accepted, and supported builds trust and emotional attachment. A considerate manager who listens and acts on employee concerns can dramatically improve morale—even small gestures, like upgrading outdated equipment, signal care and responsiveness (Bauer et al., 2007; Dvorak, 2007).

Stress & Role Clarity

Stress levels—whether from environmental factors (noise, heat), interpersonal conflict, or role ambiguity—can erode satisfaction. However, not all stress is harmful. Challenge stressors, such as time pressure or responsibility, can enhance engagement and satisfaction when framed as opportunities for growth (Podsakoff et al., 2007; Kinicki et al., 2002).

Work–Life Balance

Work–life balance reflects the ability to meet demands at work without sacrificing personal well-being. It’s increasingly prioritized in hybrid and remote work contexts, and research shows:

- Employees with better work–life integration experience higher satisfaction, lower stress, and better health outcomes

- Lack of balance can lead to emotional exhaustion, reduced commitment, and higher absenteeism

- Supportive policies like flexible schedules, mental health days, and parental leave can buffer burnout and strengthen retention (Allen et al., 2020)

Work–life balance also interacts with personality traits such as conscientiousness and locus of control—those who feel personally responsible for managing demands may struggle more when balance is hard to achieve.

Consequences of Positive Work Attitudes

Organizations pay close attention to employees’ job satisfaction and organizational commitment because these attitudes shape critical workplace behaviors.

For decades, researchers have debated whether happy employees truly perform better. Meta-analyses suggest a moderate correlation—around 0.30—between job satisfaction and performance, indicating that while satisfied employees are generally more productive, the relationship is far from one-to-one (Judge et al., 2001; Riketta, 2008). The connection between organizational commitment and performance tends to be even weaker (Mathieu & Zajac, 1990; Wright & Bonett, 2002). Several factors explain this modest link. Motivation alone doesn’t guarantee performance—skills, job demands, and environmental constraints play a major role. In fact, the attitude–performance link tends to be stronger in professional roles, like research or engineering, than in routine or manual labor where performance may be externally controlled (Riketta, 2002). Dissatisfied workers may still perform adequately due to fear of termination, a desire for promotion, or personal work ethic. In other words, while work attitudes increase the likelihood of better performance, they do not ensure it.

Interestingly, work attitudes are more strongly tied to organizational citizenship behaviors (OCBs)—voluntary actions that support the workplace but fall outside formal job descriptions. Examples include mentoring new employees, helping coworkers, and taking initiative without being asked. Satisfied and committed employees are also less likely to be absent, more likely to stay with their organization, and less prone to workplace aggression (Organ & Ryan, 1995; LePine et al., 2002; Hershcovis et al., 2007). These behaviors contribute to a healthier, more resilient workplace. Positive work attitudes also affect life beyond the job. Research shows a strong connection between job satisfaction and overall life satisfaction (Tait et al., 1989; Cohen, 1993), which makes sense given how much time people spend at work. Employees who feel fulfilled professionally tend to report greater happiness, lower stress, and stronger interpersonal relationships.

On a broader scale, organizations benefit as well. A satisfied workforce has been linked to improved customer satisfaction, higher retention, stronger profitability, and better safety records (Harter, Schmidt, & Hayes, 2002). These outcomes suggest that fostering positive work attitudes isn’t just about individual well-being—it’s also a smart business strategy.

Assessing Work Attitudes in the Workplace

Because work attitudes such as job satisfaction and organizational commitment are linked to performance, retention, and engagement, organizations benefit from systematically tracking these attitudes. Monitoring employee sentiment can help identify companywide issues that may be driving disengagement or turnover—and guide targeted interventions to improve morale and productivity.

Two widely used methods for assessing work attitudes are employee surveys and exit interviews.

Attitude Surveys

Many organizations—including KFC Corporation, Long John Silver’s Inc., SAS Institute, and Google—conduct regular surveys to gauge employee satisfaction, commitment, and engagement. These surveys are most effective when:

- Responses are confidential, ensuring employees feel safe to share honest feedback.

- Management follows through on survey results with visible action. When employees perceive that feedback is ignored, they may become cynical and disengaged, undermining future survey efforts.

Surveys can also be used to track trends over time, compare departments, and evaluate the impact of organizational changes. However, their success depends on the credibility of leadership and the organization’s commitment to transparency and improvement (Kammeyer-Mueller, Rubenstein, & Barnes, 2024).

Exit Interviews

Exit interviews offer a valuable opportunity to learn why employees are leaving and what could be improved. These interviews are typically conducted by HR professionals, not direct managers—especially since managers may be part of the reason for the departure. When conducted thoughtfully, exit interviews can uncover patterns of dissatisfaction, highlight cultural or leadership issues, and inform retention strategies.

Together, these tools help organizations diagnose workplace climate, predict turnover, and strengthen employee experience—making them essential components of strategic organizational communication.

Insider Edge

Navigating Toxic Supervision with Communication Intelligence

This Insider Edge equips employees with strategies to respond constructively when working under a supervisor who undermines workplace well-being through poor interpersonal conduct, ethical violations, and disregard for organizational justice and work-life balance.

Recognizing the Red Flags

Supervisors who exhibit the following behaviors can severely damage employee morale and organizational culture:

- Poor person-environment fit: Misalignment between the supervisor’s values and the organization’s mission.

- Psychological contract violations: Breaking implicit promises of fairness, respect, and support (Robinson & Rousseau, 1994).

- Abuse of organizational justice: Disregard for fairness in decision-making, treatment, and communication (Adamovic, 2023).

- Disrespectful relationships: Hostility, gossip, or exclusionary behavior that erodes trust (Ding et al., 2025).

- Stress induction and neglect of work-life balance: Creating unrealistic demands and ignoring employee well-being (Gurung et al., 2025).

Research-Based Insights

| Issue | Research Insight | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Psychological contract breach | Violations reduce trust, satisfaction, and retention | Robinson & Rousseau (1994) |

| Organizational injustice | Leads to burnout, bullying, and disengagement | Neall, Li, & Tuckey (2021) |

| Negative supervisor behavior | Triggers rumination and interpersonal deviance | Ding et al. (2025) |

| Work-life imbalance | Increases stress and reduces productivity | Gurung et al. (2025) |

Strategic Employee Responses

- Document and Reflect

- Keep records of interactions and decisions that feel unjust or harmful.

- Reflect on patterns to identify systemic issues versus isolated incidents.

- Engage in Constructive Dialogue

- Use assertive communication to express concerns respectfully.

- Frame feedback around shared goals and organizational values.

- Seek Support Networks

- Build alliances with trusted colleagues or mentors.

- Use internal communication channels to share concerns safely.

- Utilize Formal Mechanisms

- Report violations through HR or ethics hotlines.

- Reference organizational policies and values when filing complaints.

- Protect Your Well-being

- Set boundaries around work hours and availability.

- Practice stress-reduction techniques and prioritize self-care.

- Explore Exit Strategies if Necessary

- If the environment remains toxic, consider internal transfers or external opportunities.

- Use communication skills to maintain professionalism during transitions.

References

Adamovic, M. (2023). Organizational justice research: A review, synthesis, and research agenda. European Management Review, 20(4), 762–782. https://doi.org/10.1111/emre.12564

Ding, C., Su, M., Pei, J., Zhu, C. J., & Zhao, S. (2025). When and why negative supervisor gossip yields functional and dysfunctional consequences on subordinate interactive behaviors. Journal of Business Ethics, 200, 137–155. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10551-024-05900-y

Gurung, V., Srivastava, S., & Chhetri, S. D. (2025). Thematic analysis on work-life balance and occupational stress: A systematic literature review. In Intelligent Computing and Optimization (pp. 410–418). Springer. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-031-73324-6_40

Neall, A. M., Li, Y., & Tuckey, M. R. (2021). Organizational justice and workplace bullying: Lessons learned from externally referred complaints and investigations. Societies, 11(4), Article 143. https://www.mdpi.com/2075-4698/11/4/143

Robinson, S. L., & Rousseau, D. M. (1994). Violating the psychological contract: Not the exception but the norm. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 15(3), 245–259. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1002/job.4030150306

Discussion Questions

- What is the difference between job satisfaction and organizational commitment? Based on research, which do you think is more strongly related to performance, and which is more strongly related to turnover? Support your answer with examples or reasoning.

- Do you think making employees happier at work is an effective way to motivate them? Why or why not? Can you think of situations where high job satisfaction might not lead to high performance? Consider factors like job type, skills, or external constraints in your response.

- In your opinion, what are the three most important factors that make employees dissatisfied with their jobs? Similarly, what are the three most important factors that influence organizational commitment? How might these factors differ across industries or roles?

- How important is pay in fostering job satisfaction and organizational commitment? Do you think pay alone is enough to make employees feel attached to a company? Why or why not? Provide examples to support your perspective.

- Do you think younger and older employees value the same factors when it comes to job satisfaction and organizational commitment? Why or why not? Similarly, do you believe there are differences between male and female employees in what makes them happier or more committed at work? Explain your reasoning with examples or observations.

Section 4.3: Work Behaviors: What Drives Action at Work?

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, you should be able to do the following:

- Define key work behaviors including job performance, organizational citizenship, absenteeism, and turnover, and illustrate their relevance in organizational contexts.

- Analyze the factors associated with each type of work behavior and evaluate their impact on individual and organizational outcomes.

Section 4.3

Work Behaviors: What Drives Action at Work?

A central goal of organizational behavior is to understand why people behave the way they do in the workplace. While human behavior is complex and multifaceted, researchers have identified four key work behaviors that consistently influence organizational outcomes:

- Job Performance

- Organizational Citizenship Behaviors (OCBs)

- Absenteeism

- Turnover

These behaviors are not the only ones studied in organizational behavior, but they represent foundational categories that help us analyze employee engagement, motivation, and retention. Understanding what these behaviors mean—and what influences them—provides valuable insight into how individuals contribute to or detract from organizational success.

Figure 4.4

| Job Performance | Organizational Citizenship Behaviors | Absenteeism | Turnover |

|---|---|---|---|

| General mental abilities | How we are treated at work | Health problems | Poor performance |

| Howe we are treated at work | Personality | Work/life balance issues | Positive work attitudes (-) |

| Stress (-) | Positive work attitudes | Positive work attitudes (-) | Stress |

| Positive work attitudes | Age of the employee | Age of the employee (-) | Personality |

| Personality | Age and tenure of the employee (-) |

Summary of Factors That Have the Strongest Influence Over Work Behaviors. Note: Negative relationships are indicated with (–).

Job Performance

Job performance refers to how effectively employees carry out their assigned duties. It is influenced by factors such as ability, motivation, personality, job design, and work attitudes. While job satisfaction and commitment can enhance performance, their impact is often moderated by skill level and situational constraints (Judge et al., 2001; Kammeyer-Mueller et al., 2024).

What Are the Major Predictors of Job Performance? Understanding what drives job performance is a central question in organizational behavior. While performance is shaped by a complex interplay of individual traits and environmental factors, research has identified several consistent predictors that help explain why some employees excel while others struggle.

Cognitive Ability

The strongest and most consistent predictor of job performance is general mental ability—including reasoning, verbal and numerical skills, and analytical thinking. These cognitive abilities are linked to academic success early in life and continue to influence performance across most job types (Kuncel, Hezlett, & Ones, 2004; Schmidt & Hunter, 2004). However, their impact varies by job complexity. In highly complex roles such as engineering, management, or research, cognitive ability is especially critical. In contrast, for routine or manual jobs, its influence is weaker but still present (Bertua, Anderson, & Salgado, 2005; Salgado et al., 2003).

Fair Treatment and Organizational Justice

How employees are treated within the organization also affects performance. When individuals perceive fairness, receive support from managers, and trust their colleagues, they are more likely to reciprocate with higher effort and engagement. This aligns with social exchange theory, which suggests that respectful treatment fosters a desire to give back through improved performance (Colquitt et al., 2001; Colquitt, Scott, & LePine, 2007; Podsakoff, MacKenzie, & Bommer, 1996).

Stress and Role Clarity

High levels of stress—especially from role ambiguity or conflicting demands—can drain mental energy and reduce focus, leading to lower performance (Gilboa et al., 2008). Stressors outside of work, such as financial strain, also impact productivity. A survey by Workplace Options found that 45% of employees reported financial stress negatively affected their job performance (Financial Stress, 2008).

Work Attitudes

Job satisfaction is a moderate predictor of performance, particularly in complex roles where employees have more autonomy. In simpler jobs, satisfaction may have less impact due to rigid procedures or machinery constraints. Interestingly, in professions like nursing, performance remains high even when satisfaction is low—likely due to ethical obligations and professional standards (Judge et al., 2001).

Personality Traits

Among personality traits, conscientiousness stands out as a reliable predictor of performance. Individuals who are organized, dependable, and achievement-oriented tend to perform better across various roles (Barrick & Mount, 1991; Dudley et al., 2006; Vinchur et al., 1998). Other traits such as emotional stability and agreeableness may also contribute, depending on the job context.

Organizational Citizenship Behaviors

OCBs are discretionary actions that go beyond formal job requirements—such as helping coworkers, volunteering for extra tasks, or promoting a positive work climate. These behaviors are strongly linked to job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and perceived fairness (Organ & Ryan, 1995; LePine et al., 2002).

What are the major predictors of citizenship behaviors? Unlike job performance, which depends heavily on cognitive ability and task-related skills, organizational citizenship behaviors (OCBs) are more closely tied to motivation, relationships, personality, and attitudes. These discretionary behaviors—such as helping coworkers, volunteering for extra tasks, and promoting a positive work climate—are shaped by how employees feel about their work and the people around them.

Social Exchange and Fair Treatment

The strongest predictor of citizenship behaviors is how employees are treated. When individuals experience fairness, support from managers, trust in colleagues, and high-quality relationships, they are more likely to reciprocate with extra-role behaviors. This aligns with social exchange theory, which suggests that respectful treatment fosters a sense of obligation to give back (Colquitt et al., 2001; Cohen-Charash & Spector, 2001; Podsakoff et al., 1996). Employees who feel valued often go beyond their formal duties to support others and contribute to the organization’s success.

Personality Traits

Personality plays a stronger role in predicting citizenship behaviors than it does in predicting job performance. Traits such as conscientiousness, agreeableness, and positive affectivity are consistently linked to higher levels of OCBs (Borman et al., 2001; Dalal, 2005; Diefendorff et al., 2002). These individuals are more likely to cooperate, show empathy, and take initiative in helping others.

Job Attitudes

Employees who are satisfied with their jobs, committed to their organizations, and engaged in their roles are more likely to perform citizenship behaviors. Positive attitudes foster a sense of belonging and motivation to contribute beyond formal expectations. Conversely, disengaged or dissatisfied employees tend to do only what is required, avoiding extra effort (Organ & Ryan, 1995; LePine et al., 2002; Riketta & Van Dick, 2005).

Age and Experience

Age is also positively associated with citizenship behaviors. Older employees may demonstrate more OCBs due to accumulated experience, deeper organizational knowledge, and a stronger sense of responsibility toward others (Ng & Feldman, 2008). Their ability to mentor, support, and guide others often grows with tenure.

Absenteeism: Causes and Organizational Responses

Absenteeism refers to unscheduled absences from work and is a key indicator of employee well-being and organizational health. While some absenteeism is unavoidable, patterns of frequent or prolonged absence can signal deeper issues in the workplace. Organizations often monitor absenteeism to identify systemic problems and improve employee engagement and retention (Hackett, 1989; Allen et al., 2020).

Health-Related Absences

Some absences stem from legitimate health concerns—such as migraines, back pain, injuries, or acute stress—and are often unavoidable (Farrell & Stamm, 1988; Martocchio et al., 2000). Penalizing employees for these absences can be counterproductive, especially when presenteeism (working while sick) risks spreading illness and reducing productivity. Instead, companies are increasingly investing in wellness programs that promote nutrition, exercise, and healthy habits—strategies shown to reduce absenteeism (Parks & Steelman, 2008).

Work–Life Balance

Absences may also result from personal obligations, such as caring for a sick relative, attending important life events, or managing academic responsibilities. Organizations that offer flexible scheduling or integrated paid time off (PTO) policies tend to see fewer unscheduled absences. For example, Lahey Clinic Foundation found that merging sick leave and PTO reduced misuse of sick days, while IBM adopted a policy allowing unlimited time off as long as work was completed (Cole, 2002; Conlin, 2007; Baltes et al., 1999).

Work Withdrawal and Attitudes

Absenteeism can also reflect work withdrawal, where employees disengage due to dissatisfaction, low commitment, or poor relationships with supervisors and peers. In such cases, absenteeism may precede turnover. Addressing absenteeism requires investigating root causes—such as job design flaws, lack of fairness, or excessive stress—and implementing corrective measures (Farrell & Stamm, 1988; Scott & Taylor, 1985).

Personal and Demographic Factors

While personality traits show inconsistent links to absenteeism, age is a reliable predictor. Contrary to stereotypes, older employees tend to have lower absenteeism rates, likely due to stronger work ethic, higher organizational loyalty, and accumulated experience (Martocchio, 1989; Ng & Feldman, 2008).

Workplace Strategy Pack

Managing Chronically Late Colleagues with Communication Intelligence

Purpose: This strategy pack equips employees with practical tools and communication strategies to address chronic lateness among colleagues—without escalating conflict or damaging team cohesion.

Why Chronic Lateness Matters

Chronically late colleagues can disrupt team dynamics, erode trust, and increase stress. Even when unintentional, repeated tardiness affects:

- Project timelines and team productivity

- Workload distribution, often burdening punctual employees

- Team morale, especially when lateness goes unaddressed

- Trust and accountability, key pillars of effective collaboration

“Time fails, even when unintentional, negatively impact teams on multiple levels” (Preston, 2022).

Research-Based Insights

Issue Research Insight Source Communication breakdowns Misaligned expectations around responsiveness and punctuality lead to frustration and inefficiency Rogers & Dorison (2025) Trust erosion Chronic lateness undermines psychological safety and team trust Preston (2022) Empathetic confrontation Constructive feedback and clear expectations improve punctuality without harming relationships HR Fraternity (2025) Strategic Employee Responses

- Assess the Impact

- Reflect on how the colleague’s lateness affects your work and the team.

- Document specific instances to clarify patterns and consequences.

- Initiate a Respectful Conversation

- Use “I” statements to express concerns (e.g., “I’ve noticed delays that impact our deadlines…”).

- Focus on shared goals rather than personal blame.

- Set Clear Expectations

- Collaboratively define what “on time” means in your team context.

- Align on deadlines, meeting norms, and communication protocols.

- Encourage Accountability

- Suggest tools like shared calendars or reminders.

- Offer support if lateness stems from personal challenges or workload issues.

- Escalate Constructively (if needed)

- If behavior persists, involve HR or a supervisor using documented examples.

- Frame the issue as a team performance concern, not a personal attack.

Sample Communication Script

“Hey [Name], I wanted to check in about our meeting start times. I’ve noticed a few delays and wanted to understand if there’s anything I can do to help. It’s important for the team that we start on time so we can stay on track. Can we talk about how we might improve this together?”

References

HR Fraternity. (2025, June 10). How to address a consistently late colleague effectively in the workplace. https://hrfraternity.com/hr-excellence/how-to-address-a-consistently-late-colleague-effectively-in-the-workplace.html

Preston, C. (2022, February 18). Chronically late? Here’s how it impacts your team. Psychology Today. https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/mental-health-in-the-workplace/202202/chronically-late-heres-how-it-impacts-your-team

Rogers, T., & Dorison, C. (2025, August 6). It’s time to streamline how we communicate at work. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2025/08/its-time-to-streamline-how-we-communicate-at-work

Turnover: Why Employees Leave and What Organizations Can Do

Turnover refers to employees voluntarily or involuntarily leaving an organization. It’s a critical metric for HR and leadership teams because high turnover disrupts operations, increases costs, and can erode morale. Turnover is shaped by a range of factors, including job satisfaction, organizational commitment, availability of alternatives, and perceived support (Mathieu & Zajac, 1990; Meyer et al., 2002).

Why do employees leave?

Performance and Pay Systems

Employee performance plays a role in turnover. Low performers are more likely to leave—either through termination, pressure to resign, or self-initiated exit due to fear of being fired. In pay-for-performance systems, poor performers may earn less, creating additional incentive to quit. However, high performers may also leave if dissatisfied, especially since they are more likely to find attractive alternatives (Williams & Livingstone, 1994).

Work Attitudes and Intentions

Work attitudes are among the strongest predictors of turnover. Employees who are unhappy, disengaged, or disconnected from their organization are more likely to consider leaving. Yet, the link between dissatisfaction and actual departure is moderated by factors like job market conditions and employability. During economic downturns, unhappy employees may stay put; in strong economies, they’re more likely to act on their intentions (Griffeth et al., 2000; Steel & Ovalle, 1984).

Organizations that invest in employee well-being often see lower turnover. For example, SAS Institute offers amenities like on-site childcare, a swimming pool, and a 35-hour workweek—resulting in a turnover rate of just 4–5%, compared to industry averages of 12–20% (Karlgaard, 2005).

Stress and Role Clarity

Stressful work environments—especially those marked by role conflict, role ambiguity, or customer mistreatment—can drive employees to seek alternatives. Companies like EchoStar Corporation address this by offering internal mobility, allowing employees to move into more desirable roles. When stress is framed as a stepping stone to growth, retention improves (Podsakoff et al., 2007; Badal, 2006).

Individual Differences

Personality traits also influence turnover. Employees who are conscientious, agreeable, and emotionally stable are less likely to quit, possibly due to better performance and stronger relationships at work (Salgado, 2002; Zimmerman, 2008). Age and tenure matter too—younger employees and new hires are more likely to leave, often due to fewer responsibilities and weaker social ties. For example, Sprint Nextel Corporation reduced early turnover by improving onboarding and addressing stressors like unclear job descriptions (Ebeling, 2007).

Workplace Strategy Pack

How to Leave Your Job Gracefully

Purpose: This guide empowers employees to exit their roles with professionalism, tact, and strategic communication—preserving relationships, protecting reputations, and ensuring a smooth transition.

Why Graceful Exits Matter

Leaving a job isn’t just a personal decision—it’s a communicative act that affects your team, your reputation, and your future opportunities. Research shows that poorly managed exits can:

- Damage professional relationships

- Tarnish reputations

- Limit future career prospects (Heidrick & Struggles, 2025)

Conversely, a graceful exit can:

- Strengthen your network

- Leave a lasting positive impression

- Open doors for future collaboration (Meyer, 2025)

Strategic Steps for a Graceful Exit

| Step | Action | Communication Tip |

|---|---|---|

| Self-Reflect | Clarify your reasons for leaving and ensure it’s the right time. | Focus on long-term goals, not short-term frustrations. |

| Review Policies | Understand your company’s resignation procedures. | Check your contract and employee handbook for notice periods and exit protocols. |

| Craft a Professional Resignation Letter | Keep it concise, respectful, and appreciative. | Express gratitude and avoid criticism. |

| Communicate in Person | Tell your manager before others. | Choose a private setting and use positive framing. |

| Support the Transition | Offer to train your replacement or document key processes. | Show commitment to a smooth handover. |

| Say Goodbye Thoughtfully | Thank colleagues and maintain connections. | Send a farewell message that reflects appreciation and optimism. |

Sample Resignation Message

“I’ve truly valued my time here and the opportunity to grow professionally. I’ve decided to pursue a new challenge that aligns with my long-term goals. I’m committed to making this transition as smooth as possible and am happy to assist in any way I can.”

References

Heidrick & Struggles. (2025). How to leave a job gracefully [PDF]. https://www.heidrick.com/-/media/heidrickcom/publications-and-reports/how_to_leave_a_job_gracefully.pdf

Meyer, H. R. (2025, February 6). The art of the graceful exit: Leaving your company without burning bridges. ADD Resource Center. https://www.addrc.org/the-art-of-the-graceful-exit-leaving-your-company-without-burning-bridges/

Tavoq. (2025). Resignation etiquette 2025: Best tips for a graceful exit. https://tavoq.com/blog/resignation-etiquette-graceful-exit

Discussion Questions

- Reflect on the distinction between job performance and organizational citizenship behaviors (OCBs). Why do you think these two types of behavior are influenced by different factors? How might a manager go about improving task performance versus encouraging OCBs in their team? Share examples of strategies or workplace environments that might boost one but not the other.

- Organizational citizenship behaviors are often praised for their positive impact—but are they always beneficial? Can you think of instances where helping behaviors or going “above and beyond” might unintentionally create stress, inefficiency, or imbalance? Discuss potential unintended consequences of OCBs and how organizations can encourage healthy boundaries.

- Imagine you’re designing a hiring strategy to identify future high performers. Based on the research discussed, which traits or qualities would you look for and why? How would you balance factors like cognitive ability, personality, and work attitudes in your selection process? What limitations might you face when applying this strategy to different types of jobs?

- Identify the major contributors to absenteeism, including both personal and organizational factors What policies or programs do you believe are most effective in reducing absenteeism while remaining fair to employees? How might flexible scheduling or integrated PTO policies address the root causes of absenteeism?

- Some companies reward managers for maintaining low turnover rates within their teams. Discuss the potential benefits and drawbacks of this approach. Could such incentives lead to unintended consequences, like retaining underperforming employees or avoiding necessary terminations? How can organizations design these programs to promote healthy retention while maintaining performance standards?

Section 4.4: The Role of Ethics and National Culture

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, you should be able to do the following:

- Analyze how job attitudes influence ethical behavior in organizational settings.

- Evaluate the impact of national culture on job attitudes and workplace behaviors across diverse organizational contexts.

Job Attitudes, Behaviors, and Ethics

Employees are more satisfied and committed when they work in organizations that foster an ethical climate—a shared understanding that doing the right thing is valued and expected. Research shows that ethical climates are associated with higher job satisfaction, stronger organizational commitment, and lower turnover intentions (Leung, 2008; Mulki et al., 2006; Valentine et al., 2006). They also promote organizational citizenship behaviors (OCBs), such as helping coworkers and going beyond formal job duties.

However, the relationship between positive work attitudes and ethical behavior is complex. While ethical climates encourage ethical conduct, high commitment to an organization may sometimes blind employees to unethical practices. In one study, employees with moderate levels of commitment were more likely to recognize and report wrongdoing, whereas those with high commitment were less likely to acknowledge ethical violations—suggesting that strong identification with a company can reduce ethical awareness (Somers & Casal, 1994).

Organizations face a dilemma when trying to prevent unethical behavior. Surveillance and monitoring—such as reading emails or tracking online activity—can reduce misconduct but may also erode trust, satisfaction, and performance. Instead, companies are encouraged to build ethical cultures that emphasize shared values, transparency, and integrity. This approach fosters ethical behavior without compromising morale (Crossen, 1993).

Job Attitudes in Cross-Cultural Communication

While many predictors of job satisfaction are universal—such as fair treatment and positive relationships—cultural differences shape how employees experience work. For example, work–family conflict reduces job satisfaction in individualistic cultures, where personal autonomy is prioritized. In collectivistic cultures, employees may offset work sacrifices by strengthening social bonds, which buffers dissatisfaction (Spector et al., 2007).

Similarly, empowerment is valued in countries like the United States, Mexico, and Poland, but in India, high levels of empowerment were linked to lower job satisfaction, possibly due to differing expectations around hierarchy and decision-making (Robert et al., 2000).

Culture also influences how work behaviors are defined. In Western cultures, helping a coworker may be seen as an OCB, while in East Asian cultures, it may be considered part of core job performance. For example, managers in Hong Kong and Japan view tolerance of difficult conditions without complaint as a performance expectation, whereas in the United States and Australia, such behaviors are considered discretionary (Lam et al., 1999).

Even norms around absenteeism and turnover vary. In China, taking time off for illness or stress is viewed as unacceptable, while in Canada, these are considered legitimate reasons for absence (Johns & Xie, 1998). These cultural differences highlight the importance of contextual sensitivity in managing global teams and designing inclusive workplace policies.

Insider Edge

Navigating Ethical Disconnects in a Global Workplace

In today’s globalized business environment, ethical standards are not always universally defined. Employees working across borders may encounter conflicting views on what constitutes “good ethics.” When these disconnects arise, how should employees respond?

Understand the Cultural Context

Ethical behavior is often shaped by national culture. Hofstede’s cultural dimensions theory highlights how values such as individualism, power distance, and uncertainty avoidance influence workplace ethics (Hofstede, 2001). Employees should begin by recognizing that ethical norms may vary across cultures—not because one is superior, but because each reflects deeply rooted societal values.

Communicate with Clarity and Respect

Organizational communication research emphasizes the importance of open dialogue in resolving ethical tensions. Fritz (2022) argues that ethical communication involves balancing competing goods—such as transparency and respect for privacy—especially in complex workplace relationships. Employees should engage in respectful conversations that seek mutual understanding rather than judgment.

Align with Organizational Ethical Culture

Organizations often establish ethical cultures through codes of conduct, leadership modeling, and communication infrastructure. According to Roy et al. (2023), ethical culture significantly influences ethical decision-making and can serve as a stabilizing force amid global ambiguity. Employees should refer to their organization’s ethical guidelines and seek guidance from ethics officers or HR when in doubt.

Practical Steps for Employees

- Reflect on personal and cultural biases before reacting.

- Ask questions to understand the rationale behind differing ethical views.

- Use organizational channels (e.g., ethics hotlines, team meetings) to raise concerns constructively.

- Document interactions when ethical clarity is needed for accountability.

- Seek mentorship from leaders who model ethical behavior.

Conclusion

Ethical disconnects are not roadblocks—they’re opportunities for growth. By leveraging organizational communication principles and embracing cultural humility, employees can transform ethical ambiguity into collaborative strength.

References

Fritz, J. M. H. (2022). Work/life relationships and communication ethics: An exploratory examination. Behavioral Sciences, 12(4), 104. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12040104

Hofstede, G. (2001). Culture’s consequences: Comparing values, behaviors, institutions and organizations across nations (2nd ed.). Sage Publications.

Roy, A., Newman, A., Round, H., & Bhattacharya, S. (2023). Ethical culture in organizations: A review and agenda for future research. Business Ethics Quarterly, 34(1), 97–138. https://doi.org/10.1017/beq.2022.44

Discussion Questions

- Reflect on the factors that influence work attitudes, such as job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and work–life balance. Which of these factors do you believe are universal across cultures, and why? Are there any factors that might be less relevant or interpreted differently in a culture you are familiar with? For example, how might collectivistic versus individualistic values shape the importance of work–life balance or autonomy? Provide specific examples to support your reasoning.

- Do you think the reasons people leave their jobs are the same across the globe? Why or why not? Consider cultural differences in values, economic conditions, and workplace norms. For instance, how might turnover drivers differ between countries with high unemployment rates versus those with strong job markets? Or between cultures that prioritize individual achievement versus group harmony? Use examples to illustrate your points.

Section 4.5: Spotlight

Leadership Evolution and Organizational Communication: The Case of Kathleen Mazzarella at Graybar

Kathleen Mazzarella’s rise from customer service representative to Chair, President, and CEO of Graybar is a compelling example of adaptive leadership grounded in organizational communication. Her early leadership style was shaped by decades of operational experience, emphasizing transactional communication—clear expectations, performance metrics, and structured decision-making. As Executive Vice President and COO, she focused on efficiency and accountability, aligning with Graybar’s historically conservative, process-driven culture (Wikipedia, 2024). This approach was effective in maintaining stability but limited the company’s agility in a rapidly evolving market.

Upon becoming CEO in 2012, Mazzarella recognized that Graybar needed to modernize. She gradually transitioned to a transformational leadership style, emphasizing vision, innovation, and employee empowerment. This shift was reflected in her communication strategy: she began promoting inclusive dialogue, investing in leadership development, and encouraging cross-functional collaboration. Her messaging evolved from directive to inspirational, reinforcing a shared purpose and long-term vision. According to communication theory, such a shift enhances employee engagement and fosters a culture of trust and innovation (Robbins & Judge, 2022).

The ability to evolve her leadership style was critical to Mazzarella’s success. Under her guidance, Graybar doubled its revenue—from $5.4 billion to over $10.5 billion—through a combination of organic growth and strategic acquisitions (Titan 100, 2024). She also led the company through digital transformation and cultural renewal, reinforcing Graybar’s identity as an employee-owned enterprise while preparing it for future challenges. Her communication style played a central role in this transformation, as she consistently framed change as a shared journey rather than a top-down mandate.

Importantly, Mazzarella’s leadership evolution did not result in public backlash or internal disruption. On the contrary, her inclusive approach to change management appears to have strengthened Graybar’s internal culture. In 2024, she promoted a new generation of leaders, signaling a commitment to succession planning and distributed leadership (Yahoo Finance, 2024). Her ability to blend legacy values with forward-thinking strategy helped avoid the resistance that often accompanies leadership transitions.

From an organizational communication perspective, Mazzarella’s success illustrates the power of adaptive messaging, emotional intelligence, and cultural alignment. By shifting from transactional to transformational communication, she not only modernized Graybar’s operations but also deepened employee commitment and organizational resilience. Her story underscores that leadership is not static—it is a communicative process that must evolve with the needs of the organization and its people.

References

Robbins, S. P., & Judge, T. A. (2022). Organizational behavior (19th ed.). Pearson.

Titan 100. (2024). Kathleen Mazzarella – Titan Hall of Fame. https://www.titan100.biz/2024-st-louis-titans/kathleen-mazzarella/

Wikipedia. (2024). Kathleen Mazzarella. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kathleen_Mazzarella

Yahoo Finance. (2024, October 21). Graybar announces leadership changes. https://finance.yahoo.com/news/graybar-announces-leadership-changes-193900063.html

Discussion Questions

- Explain how CEO Kathleen Mazzarella’s leadership style changed from her time at Graybar.

- How important is the ability to change and evolve one’s own situational leadership style?

- What possible repercussions might be associated with encouraging risk taking in an organization?

Section 4.6: Conclusion

Work attitudes reflect employees’ emotional and cognitive evaluations of their job and organization. Key constructs such as job satisfaction and organizational commitment are closely linked to critical outcomes, including absenteeism, performance, and turnover. As a result, organizations actively monitor employee sentiments and implement strategies to foster more positive attitudes.

Core behaviors that drive organizational effectiveness—namely job performance, organizational citizenship behaviors, absenteeism, and turnover—are shaped by a dynamic interplay of individual traits and contextual influences. These underlying factors, along with their impact on work attitudes and behaviors, will be explored in greater depth in subsequent chapters.

Section 4.7: Case Study and Exercises

Ethical Dilemma Case Study

Confidentiality vs. Accountability in the Workplace

You are a department manager at a mid-sized advertising agency. Your team recently completed an anonymous attitude survey administered by HR. The survey was designed to assess workplace climate, and employees were assured that their responses would remain confidential.

After reviewing the results, you learn that three employees reported experiencing harassment by senior colleagues and described the department as a hostile work environment. The survey does not disclose names, and you have no direct knowledge of who the victims or alleged harassers are.

However, the HR representative who administered the survey is a close friend. You know they have access to demographic data that could help you identify the individuals involved. You feel a strong urge to act—but doing so may require breaching confidentiality.

The Dilemma

You are torn between two competing ethical obligations:

- Protecting confidentiality: Employees were promised anonymity. Breaching this trust could undermine future reporting and violate ethical and possibly legal standards.

- Ensuring safety and accountability: Harassment is a serious issue. Ignoring it could perpetuate harm and expose the company to liability.

You believe your friend in HR could help you identify the victims based on demographic clues—but doing so would violate the spirit (and possibly the letter) of the confidentiality agreement.

What do you do?

Ethical Considerations

- Confidentiality vs. Duty of Care: How do you protect employee privacy while ensuring a safe work environment?

- Friendship vs. Professional Boundaries: Is it ethical to leverage a personal relationship to gain confidential information?

- Transparency vs. Discretion: How do you communicate your intentions to the team without compromising sensitive information?

- Trust vs. Action: Will acting on assumptions erode trust more than inaction?

Strategy for Resolution

1. Respect Confidentiality

Do not attempt to identify individuals through informal channels. Uphold the integrity of the survey process.

2. Initiate a Formal Response

Work with HR to:

- Launch a department-wide initiative on workplace respect and anti-harassment.

- Offer anonymous follow-up channels (e.g., digital suggestion box, ombudsperson).

- Reinforce reporting mechanisms and protections for whistleblowers.

3. Create a Safe Culture

- Host facilitated discussions on workplace behavior and inclusion.

- Provide training on harassment prevention and ethical leadership.

- Encourage open dialogue without pressuring disclosure.

4. Monitor and Support

- Observe team dynamics discreetly.

- Check in with employees individually to offer support without probing.

- Document any concerns and escalate appropriately if new information arises.

Empowerment Tip

Ethical leadership means protecting both people and principles. When trust is at stake, transparency and process matter more than speed. You don’t need to know who was harmed to start making the workplace safer for everyone.

References

CecureUs. (2024, July 25). Real-life scenarios of ethical dilemmas at workplace and how to handle them. https://cecureus.com/real-life-scenarios-of-ethical-dilemmas-at-workplace-and-how-to-handle-them/

Ethics Unwrapped. (n.d.). Case studies. University of Texas at Austin. https://ethicsunwrapped.utexas.edu/case-studies

FasterCapital. (2025). Business ethics case study: Uber’s ethical quandaries—from harassment claims to data privacy. https://fastercapital.com/content/Business-ethics-case-study–Uber-s-Ethical-Quandaries–From-Harassment-Claims-to-Data-Privacy.html

Individual Exercise

Reading and Responding to Employee Instagram

You found out that one employee from your small company has created an Instagram about the company. Other current and ex-employees are also posting on this Instagram, and the picture they are painting is less than flattering. They are talking about their gripes, such as long work hours and below-market pay, and how the company’s products are not great compared to those of competitors. Worse, they are talking about the people in the company by name. There are a couple of postings mentioning you by name and calling you unfair and unreasonable.

- What action would you take when you learn the presence of this Instagram? Would you take action to shut it down? How?

- Would you do anything to learn the identity of the owner of the Instragram account? If you found out, what action would you take to have the employee disciplined?

- What would you change within the company to deal with this situation?

- Would you post on this Instagram page? If so, under what name, and what comments would you post?

References

Ajzen, I., & Kruglanski, A. W. (2019). Reasoned action in goal-directed behavior. Psychological Review, 126(5), 774–786. https://doi.org/10.1037/rev0000153

Allen, T. D., French, K. A., Dumani, S., & Shockley, K. M. (2020). A cross-national meta-analytic examination of predictors and outcomes associated with work–family conflict. Journal of Applied Psychology, 105(6), 539–576. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000458

Badal, S. (2006). Retention strategies in high-stress environments. Gallup Management Journal. Cohen, A. (1991). Career stage as a moderator of organizational commitment–turnover relationship. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 12(2), 123–135. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.4030120204

Baltes, B. B., Briggs, T. E., Huff, J. W., Wright, J. A., & Neuman, G. A. (1999). Flexible and compressed workweek schedules: A meta-analysis of their effects on work-related criteria. Journal of Applied Psychology, 84(4), 496–513. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.84.4.496

Barrick, M. R., & Mount, M. K. (1991). The Big Five personality dimensions and job performance: A meta-analysis. Personnel Psychology, 44(1), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.1991.tb00688.x

Bertua, C., Anderson, N., & Salgado, J. F. (2005). The predictive validity of cognitive ability tests: A UK meta-analysis. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 78(3), 387–409. https://doi.org/10.1348/096317905X26994

Borman, W. C., Penner, L. A., Allen, T. D., & Motowidlo, S. J. (2001). Personality predictors of citizenship performance. International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 9(1–2), 52–69. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2389.00163

Cohen, A. (1993). Organizational commitment and turnover: A meta-analysis. Academy of Management Journal, 36(5), 1140–1157. https://doi.org/10.5465/256650

Cohen-Charash, Y., & Spector, P. E. (2001). The role of justice in organizations: A meta-analysis. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 86(2), 278–321. https://doi.org/10.1006/obhd.2001.2958

Cole, C. L. (2002). Sick of absenteeism? HR Magazine, 47(7), 76–82. Conlin, M. (2007, December 3). Smashing the clock. BusinessWeek.

Colquitt, J. A., Scott, B. A., & LePine, J. A. (2007). Trust, trustworthiness, and trust propensity: A meta-analytic test of their unique relationships with risk taking and job performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(4), 909–927. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.92.4.909

Crossen, B. (1993, October 20). Companies try to monitor workers more closely, but the effort can backfire. Wall Street Journal.

Dalal, R. S. (2005). A meta-analysis of the relationship between organizational citizenship behavior and counterproductive work behavior. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(6), 1241–1255. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.90.6.1241

Diefendorff, J. M., Brown, D. J., Kamin, A. M., & Lord, R. G. (2002). Examining the roles of job involvement and work centrality in predicting organizational citizenship behaviors and job performance. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 23(1), 93–108. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.123

Dudley, N. M., Orvis, K. A., Lebiecki, J. E., & Cortina, J. M. (2006). A meta-analytic investigation of conscientiousness in the prediction of job performance: Examining the intercorrelations and incremental validity of narrow traits. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91(1), 40–57. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.91.1.40 Financial Stress. (2008). Workplace Options Survey.

Ebeling, A. (2007, June 11). SAS: The best kept secret in software. Forbes. Griffeth, R. W., Hom, P. W., & Gaertner, S. (2000). A meta-analysis of antecedents and correlates of employee turnover: Update, moderator tests, and research implications. Journal of Management, 26(3), 463–488. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920630002600305

Farrell, D., & Stamm, C. L. (1988). Meta-analysis of the correlates of employee absence. Human Relations, 41(3), 211–227. https://doi.org/10.1177/001872678804100302

Gilboa, S., Shirom, A., Fried, Y., & Cooper, C. (2008). A meta-analysis of work demand stressors and job performance: Examining main and moderating effects. Personnel Psychology, 61(2), 227–271. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2008.00113.x

Hackett, R. D. (1989). Work attitudes and employee absenteeism: A synthesis of the literature. Journal of Occupational Psychology, 62(3), 235–248. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8325.1989.tb00493.x

Harter, J. K., Schmidt, F. L., & Hayes, T. L. (2002). Business-unit-level relationship between employee satisfaction, employee engagement, and business outcomes. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(2), 268–279. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.87.2.268

Hoffman, B. J., Blair, C. A., Meriac, J. P., & Woehr, D. J. (2007). Expanding the criterion domain? A quantitative review of the OCB literature. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(2), 555–566. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.92.2.555

Horowitz, J. M., & Parker, K. (2023). How Americans view their jobs. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2023/03/30/how-americans-view-their-jobs/

Ilies, R., Nahrgang, J. D., & Morgeson, F. P. (2007). Leader–member exchange and citizenship behaviors: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(1), 269–277. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.92.1.269

Johns, G., & Xie, J. L. (1998). Perceptions of absence from work: People’s Republic of China versus Canada. Journal of Applied Psychology, 83(2), 515–530. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.83.2.515

Judge, T. A., Thoresen, C. J., Bono, J. E., & Patton, G. K. (2001). The job satisfaction–job performance relationship: A qualitative and quantitative review. Psychological Bulletin, 127(3), 376–407. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.127.3.376

Kammeyer-Mueller, J. D., Rubenstein, A. L., & Barnes, T. S. (2024). The role of attitudes in work behavior. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 11, 221–250. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-101022-101333

Karlgaard, R. (2005, May 9). The best boss. Forbes. Mathieu, J. E., & Zajac, D. M. (1990). A review and meta-analysis of the antecedents, correlates, and consequences of organizational commitment. Psychological Bulletin, 108(2), 171–194. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.108.2.171

Kristof-Brown, A. L., Zimmerman, R. D., & Johnson, E. C. (2005). Consequences of individuals’ fit at work: A meta-analysis of person–job, person–organization, person–group, and person–supervisor fit. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(5), 1016–1032. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.90.5.1016

Kuncel, N. R., Hezlett, S. A., & Ones, D. S. (2004). Academic performance, career potential, creativity, and job performance: Can one construct predict them all? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 86(1), 148–161. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.86.1.148

Lam, S. S. K., Hui, C., & Law, K. S. (1999). Organizational citizenship behavior: Comparing perspectives of supervisors and subordinates across four international samples. Journal of Applied Psychology, 84(4), 594–601. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.84.4.594

LePine, J. A., Erez, A., & Johnson, D. E. (2002). The nature and dimensionality of organizational citizenship behavior: A critical review and meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(1), 52–65. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.87.1.52

Leung, A. S. M. (2008). Matching ethical work climate to in-role and extra-role behaviors in a collectivist work setting. Journal of Business Ethics, 79(1–2), 43–55. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-007-9392-6

Martocchio, J. J. (1989). Age-related differences in employee absenteeism: A meta-analysis. Psychology and Aging, 4(3), 409–414. https://doi.org/10.1037/0882-7974.4.3.409

Martocchio, J. J., Harrison, D. A., & Berkson, H. M. (2000). The relationship between health and absenteeism: A meta-analysis. Human Resource Management Review, 10(3), 295–315. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1053-4822(00)00035-7

Mathieu, J. E., & Zajac, D. M. (1990). A review and meta-analysis of the antecedents, correlates, and consequences of organizational commitment. Psychological Bulletin, 108(2), 171–194. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.108.2.171

Meyer, J. P., Stanley, D. J., Herscovitch, L., & Topolnytsky, L. (2002). Affective, continuance, and normative commitment to the organization: A meta-analysis. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 61(1), 20–52. https://doi.org/10.1006/jvbe.2001.1842

Mulki, J. P., Jaramillo, F., & Locander, W. B. (2006). Ethical climate and turnover intention in sales. Journal of Business Research, 59(12), 1231–1236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2006.03.004

Ng, T. W. H., & Feldman, D. C. (2008). The relationship of age to ten dimensions of job performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(2), 392–423. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.93.2.392

Organ, D. W., & Ryan, K. (1995). A meta-analytic review of attitudinal and dispositional predictors of organizational citizenship behavior. Personnel Psychology, 48(4), 775–802. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.1995.tb01781.x

Parks, K. M., & Steelman, L. A. (2008). Organizational wellness programs: A meta-analysis. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 13(1), 58–68. https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.13.1.58

Podsakoff, N. P., LePine, J. A., & LePine, M. A. (2007). Differential challenge stressor–hindrance stressor relationships with job attitudes, turnover intentions, and health. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(2), 438–454. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.92.2.438

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., & Bommer, W. H. (1996). Transformational leader behaviors and substitutes for leadership as determinants of employee satisfaction, commitment, trust, and organizational citizenship behaviors. Journal of Management, 22(2), 259–298. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920639602200204

Probst, R. C., T. M., Martocchio, J. J., Drasgow, F., & Lawler, J. J. (2000). Empowerment and continuous improvement in the United States, Mexico, Poland, and India: Predicting fit on the basis of the dimensions of power distance and individualism. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85(5), 643–658. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.85.5.643

Riketta, M. (2002). Attitudinal organizational commitment and job performance: A meta-analysis. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 23(3), 257–266. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.141

Riketta, M., & Van Dick, R. (2005). Foci of attachment in organizations: A meta-analytic comparison of the strength and correlates of workgroup versus organizational identification. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 67(3), 490–510. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2004.06.001

Salgado, J. F. (2002). The Big Five personality dimensions and counterproductive behaviors. International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 10(1–2), 117–125. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2389.00198 Steel,

Salgado, J. F., Anderson, N., Moscoso, S., Bertua, C., & De Fruyt, F. (2003). A meta-analytic study of general mental ability validity for different occupations in the European Community. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(6), 1068–1081. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.6.1068 S

Schmidt, F. L., & Hunter, J. E. (2004). General mental ability in the world of work: Occupational attainment and job performance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 86(1), 162–173. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.86.1.162

Scott, K. D., & Taylor, G. S. (1985). An examination of conflicting findings on the relationship between job satisfaction and absenteeism: A meta-analysis. Academy of Management Journal, 28(3), 599–612. https://doi.org/10.5465/256122

Somers, M. J., & Casal, J. C. (1994). Organizational commitment and whistle-blowing: A test of the reformer and the organization man hypotheses. Group & Organization Management, 19(3), 270–284. https://doi.org/10.1177/1059601194193004

Spector, P. E., Allen, T. D., Poelmans, S., Lapierre, L. M., Cooper, C. L., O’Driscoll, M., … & Brough, P. (2007). Cross-national differences in relationships of work demands, job satisfy action, and turnover intentions with work–family conflict. Personnel Psychology, 60(4), 805–835. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2007.00092.x

Steel, R. P., & Ovalle, N. K. (1984). A review and meta-analysis of research on the relationship between behavioral intentions and employee turnover. Journal of Applied Psychology, 69(4), 673–686. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.69.4.673

Tait, M., Padgett, M. Y., & Baldwin, T. T. (1989). Job and life satisfaction: A reevaluation of the strength of the relationship and gender effects. Journal of Applied Psychology, 74(3), 502–507. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.74.3.502