2 Asking Patient Focused Clinical Questions

In clinical care, the process of EBP involves the five steps we looked at in the last chapter. It begins with developing one or more focused questions which inform the approach to locating relevant evidence in the second step of the process. Relevant items are critically appraised for trustworthiness in step three to determine if the quality of evidence is sufficient to warrant application to the situation that instigated the questions in step one. The evidence gathered and evaluated is then incorporated into a collaborative patient-centered decision that includes the practitioner’s experience, the context of the clinical situation and the needs and preferences of the patient. In this chapter, we will focus on the first step in the process – asking focused clinical questions.

Learning Objectives

As a result of engaging with the content of this chapter, you will be able to:

- Identify the minimal components that should be included in every focused clinical question.

- Describe the components of the PPAARE method of formulating focused clinical questions.

- Construct patient focused clinical questions using the PPAARE method applicable to situations related to individual patient care and patient experiences or perceptions.

- Define the key vocabulary terms of the chapter.

Focused clinical questions

Formulating focused questions is a key skill to success in EBP. While the evidence-based process can be ap 32plied to specific populations of people, we will emphasize the application to the individual patient, as professionals in the clinical and diagnostic sciences are primarily engaged in the delivery of care to the individual. Focused questions often arise as part of the care process. For example, consider the case of Bobbi Smith.

Ms. Smith, an overweight, African-American, 55-year-old office worker, was admitted with acute Cholecystitis, elevated white blood cell count, and a fever of 102 degrees Fahrenheit. She has undergone an open cholecystectomy and has been transferred to the floor. It is the second day post-op. She has an NG2 to continuous low wall suction, one peripheral IV, and a large abdominal dressing. Her orders are as follows: progressed diet to increased fat diet as tolerated; D5 ½ NS with 40 mEQ KCl at 125 mL per hour; turn, cough, and deep breath Q2H; incentive spirometer Q2H while awake; morphine sulfate 10 milligrams IM Q4H for pain; ampicillin 2g IVPB Q6H; chest X-ray in AM.

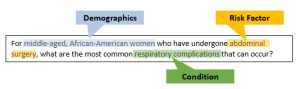

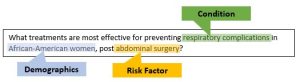

Each of these factors contributes to a focused clinical question. Focused clinical questions always include the following elements:

- A specific condition or outcome of interest

- Individual demographics

- Individual risk factors

These details are essential in finding answers that fit with the individual the details of your case and are needed to guide and focus your information search.

There are many questions that might come to mind in any given clinical situation. Let’s look at a couple of focused clinical questions that could arise from the scenario with Ms. Smith.

These two examples represent the barest elements of an evidence-based search question, but we can incorporate more factors to better target our care to our specific patient.

The PPAARE Approach

Before accessing evidence-based resources, careful planning of the search strategy is necessary. The first step in planning is to identify the situation that requires you to implement the evidence-based process. A systematic approach is valuable to use for defining the components of the situation. Professionals who are new to the evidence-based process might find it useful to break the situation they face into manageable components before implementing a search strategy for evidence. For this reason, Dr. Ellen Rogo (2021, pg. 59) has developed a mnemonic for developing focused clinical questions that is designed to ensure that each aspect of EBP is incorporated into the question – PPAARE. The acronym stands for Problem, Patient, Action, Alternative, Result, Evidence. While other approaches to asking focused clinical questions exist – Patient or Problem/Intervention/Comparison/Outcome (PICO) (Schlosser, et al., 2007), Patient or Problem/Intervention/Comparison/Outcome/Timeframe (PICOT) (Haynes, 2012), or Patient or Problem/Intervention/Comparison/Outcome/Context of Intervention (PICOC) (Petticrew and Roberts, 2006)- they all follow a format that combines Patient or Problem into the same element. Rogo ‘s format separates the patient and the problem into distinct individual elements, ensuring that the patient is always taken into consideration. Translating a healthcare situation into small pieces makes it easier for the health care professional to identify the vital elements to use in a search for relevant evidence. These components also assist the practitioner in writing focused clinical questions to guide the search for evidence.

Let’s take a closer look at each component in the PPAARE Approach.

Problem

The first P in PPAARE represents the Problem. For an individual care situation, the problem can relate to a disease or condition, such as diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, asthma, nutritional deficiency, or osteoporosis.

Patient

The second P in PPAARE represents the Patient. When faced with a client care circumstance, the need is related to an individual for (patient or client). For individuals, we are interested in demographic factors such as age, ethnicity, gender, and educational level, and modifiable risk factors, including smoking and other unhealthy behaviors.

Action

The first a in PPAARE stands for the Action that the health care provider or patient wants to take. For a clinical situation about patient care, actions can relate to:

- Diagnosis – the identification of the nature of an illness or other problem by examination of the symptoms and diagnostic tests – laboratory testing, radiology procedures, endoscopy procedures and other types of monitoring provide healthcare professionals with data specific to the patient’s situation to analyze

- Etiology – the causes of a disease

- Prognosis – how a disease may progress, or expected outcomes

- Prevention – how a disease process may be stopped or kept from happening

- Self-management procedures – assisting the patient in taking responsibility for their own well-being

- Interventions – a treatment or program to alleviate the disease or its symptoms

- treatments – any action, medicine, or other therapy to treat or cure a disease

- medications – drugs or medicines

- indications – the circumstances in which a given treatment or intervention should be used

- contraindications – the circumstances in which a given treatment or intervention should NOT be used

- Follow-up care -care necessary after the performance of an intervention or treatment

- Evaluation of outcome – determination of the desirability of the results of the intervention

-

Outcomes – measurable or observable results of illness or treatment

-

direct or primary outcomes – endpoints that are intended to be directly impacted by the intervention

-

indirect or surrogate outcomes – an indirect outcome such as a physiologic measure, lab test, or imaging test that reflects another type of outcome, usually an outcome that matters. Surrogates are selected based on the association of a physiological or biological measure with another known clinical endpoint (e.g., morbidity, mortality)

-

clinically relevant outcomes or outcomes that matter – Clinically relevant outcomes that provide direct measures of the disease. The practical importance of the treatment effect or whether the outcome is significant to the patient. It encompasses more than clinical data, including other outcomes that patients and providers care about, such as the patient’s ability to function or the cost of care. Outcomes that matter include such factors as quality of life as well as mortality.

-

- Understanding patient experiences

Alternative Action

The Alternative for the action, the second A in PPAARE, is not always identified. There is no need to force an alternative action; however, when one is available, a comparison can be useful. These can include no treatment, usual care, or watchful waiting. There are situations in which an alternative makes sense. For example, a physician assistant might want to prescribe a newer drug on the market and compare its effectiveness and side effects with one that the practice has used for several years. A surgeon might compare gastric bypass to laproscopic gastric banding to determine which has longer-lasting weight loss results.

Result

The R component represents the Result of the action. The goal or outcome that the health care professional intends to achieve needs to be carefully considered and articulated. The result is directly linked to the Patient, Problem and Actions components to produce, improve, or reduce the outcome related to the patient, or to understand the patient’s experiences or perceptions. For example, consider the following hypothetical situation for a Problem related to a diabetic condition. The Patient is a 32-year-old male Native American. The Action is a diet restricting carbohydrates combined with an exercise program to reduce BMI, compared with the Alternative Action of consuming oral hypoglycemic medication. The Result would be a reduction in hemoglobin A1C scores below a 5.7% level. Another consideration is the time frame in which the result is evident in the outcome.

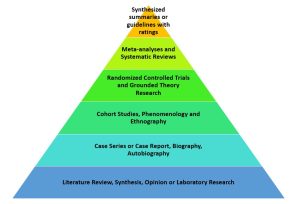

Evidence

The last component of PPAARE corresponds to the level of evidence that you locate to answer the focused question. A practitioner always searches for, then uses, the best, current evidence available and relevant to the clinical situation. When higher levels of quantitative evidence, such as synthesized summaries or clinical practice guidelines with grades or ratings of quality do not exist or are not current, the practitioner is faced with searching for meta-analysis, systematic reviews, randomized controlled trials, and observational studies (case control studies, case studies, and case reports). Likewise, when higher levels of naturalistic evidence such as evidence synthesis, confirmatory studies, and theory construction research do not exist or are not current the practitioner is faced with searching for single group research and single case research. As you’ve been begin to search for evidence, keep in mind the hierarchy on the quantitative and qualitative evidence pyramids (See Figure 2-1 below) and always search for the highest level available whatever it might be. We will discuss the levels of evidence in greater detail in Ch. 3. For writing our focused clinical questions, we will assume that we are looking for the highest level of evidence available.

Evidence Pyramid for Levels of Evidence

One way of categorizing medical information is to assign the level of evidence to a given resource. Several systems have been developed for designating evidence levels. It is common to refer to these systems as evidence pyramids. See Figure 2-1 for one example of an evidence pyramid.

Figure 2-1: Evidence Pyramid

An evidence pyramid presents the quality of evidence from lowest quality at literature reviews and opinion papers to highest quality at synthesized summaries or guidelines with ratings.

Using the PPAARE Approach to Create Focused Clinical Questions

Let’s see how the PPAARE Approach can be used to help us create focused clinical questions. Let’s start with the scenario of Ms. Bobbi Smith that we looked at earlier.

Ms. Smith, an overweight, African-American, 55-year-old office worker, was admitted with acute Cholecystitis, elevated white blood cell count, and a fever of 102 degrees Fahrenheit. She has undergone an open cholecystectomy and has been transferred to the floor. It is the second day post-op. She has an NG2 to continuous low wall suction, one peripheral IV, and a large abdominal dressing. Her orders are as follows: progressed diet to increased fat diet as tolerated; D5 ½ NS with 40 mEQ KCl at 125 mL per hour; turn, cough, and deep breath Q2H; incentive spirometer Q2H while awake; morphine sulfate 10 milligrams IM Q4H for pain; ampicillin 2g IVPB Q6H; chest X-ray in AM.

Let’s start by identifying the PPAARE components. It can be helpful to use a table or grid to organize your thoughts in this first step.

| PPAARE Component | Scenario Component |

| Identify the problem related to the disease or condition | cholecystitis |

| Identify the person related to his or her demographics and risk factors | overweight female |

| Identify the action related to the person’s diagnosis or diagnostic tests, etiology, prognosis, treatment or therapy, harm, prevention, patient education, follow-up care, or evaluation | etiology |

| Identify the alternative action when there is one ** optional** | n/a |

| Identify the result of the action to produce, improve, or reduce the outcome for the patient. | Understanding the etiology of cholecystitis can help us guide other patients so they avoid needing surgery |

So, for this analysis, we can create the following focused question:

What causes (etiology) cholecystitis can be identified for overweight females that could be useful in patient education?

But this isn’t the only focused clinical question that can arise from this scenario. Let’s reanalyze the scenario choosing different components.

| PPAARE Component | Scenario Component |

| Identify the problem related to the disease or condition | cholecystitis |

| Identify the person related to his or her demographics and risk factors | overweight female |

| Identify the action related to the person’s diagnosis or diagnostic tests, etiology, prognosis, treatment or therapy, harm, prevention, patient education, follow-up care, or evaluation | Treatment – open surgery |

| Identify the alternative action when there is one ** optional** | alternatives to open surgery |

| Identify the result of the action to produce, improve, or reduce the outcome for the patient. | reduce post-intervention complications |

This analysis leads us to a different focused clinical question:

What alternatives to open cholecystectomy exist for treating cholecystitis in overweight females, and which alternative(s) have the lowest risk for post-intervention complications?

Formulas for Focused Clinical Questions

A formula for writing focused clinical questions that are centered on Patient Care that might be useful to you is:

Patient Care Questions

What evidence is available to determine whether a person with [PROBLEM] who is [PERSON demographics or risk factors] benefits from [ACTION] compared to [ALTERNATIVE ACTION] to produce, improve or reduce the [RESULT]?

Using this formula, the first question above could be phrased as:

What evidence is available to determine whether a person with cholecystitis[PROBLEM] who is an overweight female[PERSON demographics or risk factors] benefits from education on the etiology of cholecystitis [ACTION] compared to those who do not receive patient education[ALTERNATIVE ACTION] to reduce the need for a cholecystectomy[RESULT]?

And the second question could be phrased as:

What evidence is available to determine whether a person with cholecystitis [PROBLEM] who is an overweight female [PERSON demographics or risk factors] benefits from open cholecystectomy[ACTION] compared to other less invasive treatment options[ALTERNATIVE ACTION] to reduce post-intervention complications[RESULT]?

It is important to note that the questions you ask are dependent on what you want to get out of the scenario. You may already know about alternative treatments for acute cholecystitis but need to know more about the use of D5 ½ NS with 40 mEQ KCl after the surgical intervention. There are no right or wrong questions to ask.

Let’s try a couple more examples just for good measure.

A 65-year-old Caucasian trans female asks about their risk of prostate cancer. Their father and brother both had prostate cancer in their late 60’s -early 70’s.

| PPAARE Component | Scenario Component |

| Identify the problem related to the disease or condition | prostate cancer |

| Identify the person related to his or her demographics and risk factors | 65-year-old trans female |

| Identify the action related to the person’s diagnosis or diagnostic tests, etiology, prognosis, treatment or therapy, harm, prevention, patient education, follow-up care, or evaluation | risk factors/diagnostic tests |

| Identify the alternative action when there is one ** optional** | no follow-up |

| Identify the result of the action to produce, improve, or reduce the outcome for the patient. | improve quality of life outcomes if prostate cancer develops |

Then, we apply our question formula to create the following question:

What evidence is available to determine whether a person with a family history of prostate cancer [PROBLEM] who is a trans female [PERSON demographics or risk factors] benefits from screening Prostate Antigen Testing[ACTION] compared to no screening[ALTERNATIVE ACTION] to improve quality of life outcomes if prostate cancer develops[RESULT]?

An alternate analysis of this same scenario may look like this:

| PPAARE Component | Scenario Component |

| Identify the problem related to the disease or condition | prostate cancer screening |

| Identify the person related to his or her demographics and risk factors | 65-year-old trans female |

| Identify the action related to the person’s diagnosis or diagnostic tests, etiology, prognosis, treatment or therapy, harm, prevention, patient education, follow-up care, or evaluation | gain knowledge of the patient’s health care experience |

| Identify the alternative action when there is one ** optional** | n/a |

| Identify the result of the action to produce, improve, or reduce the outcome for the patient. | improve trust in the healthcare system |

Patient Experience and Perception Questions

In this situation, we are looking to understand patient experiences and perceptions. This necessitates structuring our focused clinical questions a little differently. In this case, we will use the following formula:

What evidence is available to determine the experiences or perceptions of [PROBLEM] in a [PERSON demographics or risk factors] patient to [ACTION] to assist them in producing, improving or reducing the [RESULT]?

Then, we apply our question formula to create the following question:

What evidence is available to determine the experiences or perceptions of prostate cancer screening [PROBLEM] in a trans female [PERSON demographics or risk factors] patient to gain knowledge of the patient’s health care experience [ACTION] that improves trust in the healthcare system [RESULT]?

Review

Exercise 2-1: Focused Clinical Questions

Summary

Healthcare professionals who are new to evidence-based practice might have difficulty in narrowing down the patient-related information to create a focused clinical question. We can use the PPAARE Approach to identify the specific pieces of information we are going to focus our question on. We have seen that there can be many different valid clinical questions that arise during a single clinical situation and each of those questions can help a healthcare team best address the needs of the patients they serve.

References

Haynes, R. Brian. Clinical Epidemiology: How to Do Clinical Practice Research. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2012.

Rogo, Ellen J. “Formulating Focused Questions and Locating Relevant Evidence.” In Evidence-Based Practice for Health Professionals, 2nd ed., 57–83. Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning, 2021.

Schlosser, Ralf W., Rajinder Koul, and John Costello. “Asking Well-Built Questions for Evidence-Based Practice in Augmentative and Alternative Communication.” Journal of Communication Disorders 40, no. 3 (May 2007): 225–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcomdis.2006.06.008.

Media Attributions

- Ask example 1

- Ask example 2

- Evidence Pyramid