3 Locating and Preparing to Cite Relevant Evidence

When faced with a clinical problem or dilemma, our first step, as we learned in Ch. 2, is to identify one or more focused clinical questions whose answers will contribute to a holistic understanding of the problem and the actions that can be taken to address it. Once the focused clinical question is developed, we must plan our approach to locating and citing the relevant evidence. This process involves four separate steps: determining the level of evidence needed to answer the question, identifying the database(s) that index evidence at that level, formulating a search strategy for that database, and collecting the relevant resources into a citation engine.

Learning Objectives

As a result of engaging with the content of this chapter, you will be able to:

- Identify the steps involved in locating and preparing to cite relevant evidence.

- Identify the source(s) best suited for identifying evidence at a particular level.

- Translate the PPAARE components into searchable words or phrases.

- Locate the desired level of relevant evidence using sources applicable to locating evidence at that level.

- Collect and organize relevant evidence using citation management tools.

- Define the key vocabulary terms of the chapter.

Determining the Level of Evidence Needed

For most of our focused clinical questions we will either be needing simple background information on disease processes, etiology, risk factors, and other similar details, or we will be looking for clinical decision-making guidelines that are based on the most current research findings. For clinical decision-making guidelines, we will definitely want to look for the highest level of evidence available. However, sometimes the answers we need are simply background information that we are lacking. When we are needing background information, professional textbooks are our best source of information. Let’s dig a little deeper into the Levels of Evidence so we understand the differences between the levels.

Levels of Evidence

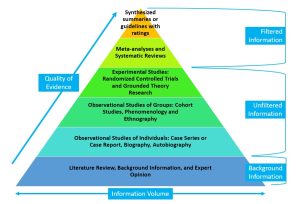

As discussed in Ch. 2, one means of categorizing medical information is to assign the level of evidence to a given resource. Before we can locate the evidence we need to answer our focused clinical questions, we need to decide what level of information is needed to answer the question we are asking. Several systems have been developed for designating evidence levels. It is common to refer to these systems as evidence pyramids. Figure 3-1 displays an evidence pyramid for types of studies published in the health professions. Let’s examine the pyramid model more closely.

Figure 3-1: Evidence Pyramid

The Evidence Pyramid illustrates both the quality or reliability of the information and the volume of information available at a particular information level. The levels can be further grouped into filtered information, unfiltered information and background information.

The levels of evidence pyramid is used to rank studies on the basis of their quality and reliability. You will note that the pyramid model illustrates both the quality and the quantity of available evidence. The higher the position on the pyramid, the stronger the evidence (Murad, et. al., 2016). Each level draws on data and research previously developed in the lower levels. The volume of information available at each level decreases as we move up in quality on the pyramid.

We can also divide the evidence pyramid into three sections. The top section consists of filtered or secondary evidence, including synthesized summaries, guidelines with ratings, systematic reviews, meta-analyses and critical appraisals. The central section includes unfiltered or primary research evidence including experimental and grounded theory studies, observational studies of groups, and observational studies of individuals. The foundational level of the pyramid includes background information and expert opinion. To determine which level of information we need to answer our focused clinical questions, we need to understand the kinds of information contained in each level.

Filtered or Secondary Information

The filtered or secondary information section of the evidence pyramid constitutes the highest level of research evidence available. These studies review all available research evidence from peer-reviewed publications and combine the findings into a cohesive set of conclusions that are supported across the body of evidence. These studies are considered “secondary” because their findings are based on someone else’s original research. In our model the filtered information is divided into two levels: synthesized summaries and guidelines with ratings, and systematic reviews and a meta-analyses.

Synthesized Summaries and Guidelines with Ratings

The peak of the pyramid includes synthesized evidence-based summaries with ratings. Evidence based clinical practice guidelines fall into this category. It is important to note that not all clinical practice guidelines fit into this level, as some are based on expert opinion or consensus and do not employ rigorous evidence appraisal protocols in their development. The ratings of statements in evidence summaries and practice guidelines at this level indicate the strength and type of evidence associated with each recommendation statement (Howlett & Rogo, 2014).

Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

The second level of the pyramid and the second source of filtered information is systematic reviews and meta-analyses. A systematic review collects the results from all available studies of a particular health topic and integrates the findings into a single, cohesive set of findings. Meta-analyses also collect information from all available research studies on a topic but go beyond systematic reviews to incorporate statistical analysis of the combined findings. Both of these types of research articles answer specific research questions by collecting and evaluating all research evidence that fits the reviewer’s selection criteria (Turner, 2014). Systematic reviews and meta-analyses are considered a lower level of evidence because they do not include a rating of the evidential support for the findings.

Unfiltered or Primary Information

The unfiltered information section of the evidence pyramid includes the primary research studies that form the basis of the systematic reviews and meta-analyses found in the filtered information documents. All the studies found in this section are reports of original research findings published in peer reviewed journals. These studies are considered primary because their findings are based on unique, documented observations by the authors. in our model, the unfiltered information is divided into 3 levels: experimental studies, observational studies of groups and observational studies of individuals. These levels are ordered by their applicability to larger populations of individuals. Randomized controlled trials and grounded theory research are most generalizable because they compare outcomes in the intervention group to a control group. Observations involving larger groups of people make those findings more applicable across the population than observations on individuals. As with the systematic reviews and meta-analyses, articles assigned to these levels of evidence are expected to be peer reviewed. However, these studies have not been subjected to initial analysis and review beyond that of the peer reviewers for each study. In most cases, unfiltered levels of evidence are difficult to apply in clinical decision making (Kendall, 2008). However, higher levels of evidence may not be available to answer every focused clinical question. In these instances, the healthcare professional will need to evaluate the primary sources carefully to determine the trustworthiness and relevance of the study to the clinical situation.

Background Information

Background information and expert opinions are not necessarily backed by research studies. Background information and expert opinion can be found in textbooks or medical books that provide basic information on a topic. They can be helpful to make sure you understand a topic and are familiar with terms associated with it.

While some textbooks can provide synthesized content backed by peer-reviewed research, it is not easy to tell which books are evidence-based and which are not without looking at the content of the book. As EBP beginners, you should assume that textbooks and other eBooks provide evidence at the background information/ expert opinion level.

Identifying the Target Database(s)

Much of locating relevant evidence depends upon the evidence-based sources available to you. You are familiar with the process of purchasing textbooks. When libraries provide resources to people, they undergo a similar process. They either have to purchase the books that you are using or subscribe to that access through the publisher. As with everything else related to health care, the purchase price and subscriptions for health related resources tend to be much higher than the cost for similar resources in other disciplines. So while academic medical centers may provide access to a wide range of resources smaller facilities may only offer one or two options. We will look at some of the most common paid resources as well as some freely available resources that you can access without a subscription.

Deciding on the level of evidence that is most appropriate will help you narrow down the array of possible information sources to the databases that are best suited to provide the level of information you need.

Resources for Finding Filtered Information

The highest level of filtered information – Guidelines with Ratings – converts the research findings of numerous studies into guides that focus on how the findings should be applied to clinical practice along with an indicator that communicates the strength of the research supporting each particular recommendation. The next level down – Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses – combines and summarizes the research findings of numerous studies that focus on answering the same research question, but do not translate those findings into actionable recommendations for clinical practice.

Resources for Guidelines with Ratings

Figure 3-2: USPSTF Breast Cancer: Screening – 2016 Recommendation Summary

| Population | Recommendation | Grade |

|---|---|---|

| Women aged 50 to 74 years | The USPSTF recommends biennial screening mammography for women aged 50 to 74 years. | B – The USPSTF recommends the service. There is high certainty that the net benefit is moderate or there is moderate certainty that the net benefit is moderate to substantial. |

| Women aged 40 to 49 years | The decision to start screening mammography in women prior to age 50 years should be an individual one. Women who place a higher value on the potential benefit than the potential harms may choose to begin biennial screening between the ages of 40 and 49 years.

|

C – The USPSTF recommends selectively offering or providing this service to individual patients based on professional judgment and patient preferences. There is at least moderate certainty that the net benefit is small. |

| All women | The USPSTF concludes that the current evidence is insufficient to assess the benefits and harms of digital breast tomosynthesis (DBT) as a primary screening method for breast cancer. | I – The USPSTF concludes that the current evidence is insufficient to assess the balance of benefits and harms of the service. Evidence is lacking, of poor quality, or conflicting, and the balance of benefits and harms cannot be determined. |

| Women with dense breasts | The USPSTF concludes that the current evidence is insufficient to assess the balance of benefits and harms of adjunctive screening for breast cancer using breast ultrasonography, magnetic resonance imaging, DBT, or other methods in women identified to have dense breasts on an otherwise negative screening mammogram. | I – The USPSTF concludes that the current evidence is insufficient to assess the balance of benefits and harms of the service. Evidence is lacking, of poor quality, or conflicting, and the balance of benefits and harms cannot be determined. |

| Women aged 75 years or older | The USPSTF concludes that the current evidence is insufficient to assess the balance of benefits and harms of screening mammography in women aged 75 years or older. | I – The USPSTF concludes that the current evidence is insufficient to assess the balance of benefits and harms of the service. Evidence is lacking, of poor quality, or conflicting, and the balance of benefits and harms cannot be determined. |

Siu, Albert L. and U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. “Screening for Breast Cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement.” Annals of Internal Medicine 164, no. 4 (February 16, 2016): 279–96. https://doi.org/10.7326/M15-2886.

Let’s look at the USPSTF recommendations for breast cancer screening. Figure 3-2, above, displays a Recommendation Summary from the USPSTF guidelines on breast cancer screening (Siu & U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, 2016). This summary shows the recommendation and the rating associated with it. These recommendations were published in 2016 and were a significant departure from traditional patient care at the time. They recommend biannual screening mammography for women aged 50 to 74 years. At the time this recommendation was published the American College of Radiology and the American Cancer Society were both recommending annual screening mammograms from age 40 on, but the research evidence did not show a significant benefit of annual screenings or improved outcomes from screening women between the ages of 40 and 49 years. So, biannual screening mammography received a grade of B for a population of women aged 50 to 74 years and a grade of C for women aged 40 to 49 years. The USPSTF identified a need for more research regarding the use of digital breast tomosynthesis, the use of breast ultrasound or MRI in women with dense breasts, and screening mammography in women over the age of 75.

Because the focus of the USPSTF is on preventive care, their recommendations are limited to those screenings and prophylactic interventions used in completely asymptomatic patients. You can find critically appraised synthesis or synopsis resources, also known as evidence-based reviews, on other topics by searching for critically appraised topics (CAP), or Patient Oriented Evidence that Matters (POEMs) (Howlett & Rogo, 2014). These recommendations can be located using advanced search filters in DynaMed Plus and the TRIP Database (see more on these resources below). The key factor to identifying resources that provide this level of evidence whether they is synthesize and summarize evidence sources that represent best available evidence and provide ratings to describe the evidential basis for the recommendation. The recommendations included in these sorts of resources address specific clinical situations and are based on the most valid, currently available high-level evidence.

Resources for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

The most well-known collection of systematic reviews is the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR). The CDSR includes Cochrane Reviews and Protocols as well as editorials and supplements, and is produced by an independent network of researchers, professionals, patients, carers, and people interested in health. The Cochrane Database is published by Wiley and is available on a subscription or pay-per-view basis, but the individual reviews and editorials can be located in the PubMed, Web of Science and Scopus databases (John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2023).

Another source of systematic reviews and meta-analyses is Epistemonikos (Coombs, 2023). Epistemonikos (epistemonikos.org) is a freely available, collaborative, multilingual database of health evidence. It is the largest source of systematic reviews relevant for health decision making, and a large source of other types of scientific evidence. Search results from Epistemonikos are divided into broad syntheses, systematic reviews, structured summaries, and primary studies.

Another free resource is the TRIP Database, which searches evidence-based medical topics from 61 EBM sites around the world, including ACP Journal Club, POEMS, Bandolier, DARE, and others. You can also use advanced search features on standard academic databases like PubMed, Web of Science and Scopus, to limit results to systematic reviews and meta-analyses.

Resources for Finding Unfiltered Information

Unfiltered information is Found in the journal articles that report original research. This research can be quantitative, basing results and conclusions on measurements that are analyzed through statistical testing, or qualitative, recording observations and experiences of individuals for groups of people with similar in similar situations. Resources for finding these journal articles are much more common and can be found in most libraries. Some excellent choices of databases that index health related studies include PubMed and Scopus.

PubMed/PubMed Central

PubMed ( https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) is a publicly available, free index of citations of biomedical literature, that was developed by the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI), the U.S. National Library of Medicine (NLM) and the National Institutes of Health (NIH). It can be accessed from anywhere with internet access. While PubMed does not include full text journal articles, it will provide links to the full text articles. Freely available full text articles are noted in the search results list.

When you open the entry for a particular article, you will find the links to the full text articles on the right side of the page. These links may include links to the publisher’s websites or links for accessing the articles through your library. If you follow the links to the publisher’s websites, you may be asked to pay for the article (but always click the link to see if it is free!). Accessing PubMed through a library website may provide links to the full text articles from journals to which the library subscribes.

PubMed Central (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/) is a companion site to PubMed. While PubMed Central indexes fewer articles than can be found on PubMed, all the articles found on PubMed Central have free full text documents associated with them. Currently, PubMed Central contains more than 8,000,000 full text articles, spanning several centuries of biomedical and life science research. Another advantage of PubMed Central is that it provides the search details on the search results page. This can be important for documenting how you located the information when writing your own articles.

Scopus

Resources for Finding Background Information

AccessMedicine

AccessMedicine is an online resource specializing in providing health care professionals with resources they need to make informed care decisions. This subscription-based resource includes access to more than 100 references including the latest editions of textbooks such as Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine and Fuster and Hurst’s The Heart. They also provide access to a differential diagnosis tool, Diagnosaurus, that allows you to browse by symptom, disease, or organ system. Users from institutions with site licenses for AccessMedicine also have access to the AccessMedicine app (available in App Store or Google Play) after signing up for a My Access account.

Proquest eBook Central

Proquest eBook Central is another subscription-based online resource that specializes in providing credible content from authoritative, scholarly sources. Ebook Central delivers with a breadth and depth of ebooks from scholarly sources, and includes resources in the natural sciences, humanities, education and business, in addition to health and medicine.

ClinicalKey

ClinicalKey is a third subscription-based collection of online resources for health and medicine information published by Elsevier. Their search interface allows you to easily select the source type to limit results to clinical guidelines or focus on drugs, and choose to search for books, journals or multimedia resources. Does NOT play well with Zotero, so citations require a lot of manual data entry.

Figure 3-3: Summary of Databases by Evidence Level

| Evidence Level |

Recommended Resources |

|---|---|

| Filtered – Secondary | Guidelines and Summaries with Ratings

U.S. Preventive Services Task Force

Systematic Reviews & Meta-Analyses

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews

|

| Unfiltered – Primary | PubMed (with University of Missouri Library links)

|

| Background – Expert Opinion | AccessMedicine

|

The links provided above may utilize University of Missouri Library resources. For resources requiring a paid subscription, you will be asked to log in with your username and password.

Information Resources to AVOID

In a world where we now carry more computing power in our pockets than was used to fly the first space shuttle, we are comfortable opening our devices and asking google any question that we can think of. This can be problematic because google searches the internet and A LOT of stuff on the internet can be questionable. Don’t believe me? Try searching for thyroid shielding during mammography (and the guy who started this misinformation actually IS a doctor…)… or benefits of colon hydrotherapy…. sometimes you can’t make this stuff up! Will google turn up some good information? Sure! But you have to be a lot more careful that the information being presented isn’t being biased by advertisers and is accurate. Even the information that is pretty solid is frequently from hospital websites that are providing information for patients and the general public. When we are making care decisions, we need the details, so this information is not at the appropriate level for our use. It also is generally not peer reviewed, so errors may inadvertently slip into the information. Resources that look pretty good, but are geared for patients include WebMD, MayoClinic.org, Healthline.com, and MedicalNewsToday.com. This information is typically written by health reporters and many of these sites have paid advertisers who may influence the perspective of the information presented.

Formulating a search strategy

It’s easier to find appropriate sources when you start with a plan.

Now that we have decided on one or more resources that we want to search, it is time to think about how we want to structure our searches to find the information we need quickly and easily!

Determining Search Terms

First, let’s go back to your PPAARE grid and question. For each PPAARE component, we want to think of alternate words or synonyms that can be included in the search. We also want to think of terms that should be excluded. Let’s look at an example.

Figure 3-4: Determining Search Terms

In the last chapter, we analyzed the following scenario:

A 65-year-old Caucasian trans female asks about their risk of prostate cancer. Their father and brother both had prostate cancer in their late 60’s -early 70’s.

| PPAARE Component | Scenario Component |

| Identify the problem related to the disease or condition | prostate cancer |

| Identify the person related to his or her demographics and risk factors | 65-year-old trans female |

| Identify the action related to the person’s diagnosis or diagnostic tests, etiology, prognosis, treatment or therapy, harm, prevention, patient education, follow-up care, or evaluation | diagnostic tests |

| Identify the alternative action when there is one ** optional** | no follow-up |

| Identify the result of the action to produce, improve, or reduce the outcome for the patient. | improve quality of life outcomes if prostate cancer develops |

We created the following question:

What evidence is available to determine whether a person with a family history of prostate cancer, who is a trans female, benefits from screening Prostate Antigen Testing compared to no screening to improve quality of life outcomes if prostate cancer develops?

Now we need to convert our PPAARE components into searchable terms.

| Search Words Corresponding to PPAARE Components | Alternative Words or Synonyms for Search Words | Search Words to be Excluded from Search |

| Prostate cancer | Prostate neoplasm | |

| Older adult | above 65, geriatric | children, adolescents |

| Trans female | ||

| Family history of prostate cancer | ||

| Diagnostic testing | PSA, Prostate Specific Antigen, screening | |

| Watchful waiting | ||

| Prostate biopsy | ||

| Unnecessary procedures | ||

| Rate of progression |

Once we have brainstormed synonyms for our search terms and determined categories of studies that should be excluded from the search, it is time to structure our search.

Structuring the Search Query

When we are searching databases, we are basically programming a set of instructions for the computer to follow. While we can enter single words or entire sentences into the search bar like we do in google, our searches are more effective if we follow some basic principles and are aware of some common tools.

One Concept at a Time

In our searchable terms grid above, we have identified 8 different concepts that describe a different part of the clinical problem we are working on. If we put all of those terms in the search box at the same time, we probably aren’t going to get any results, because the exact scenario we are facing may not have been written about yet. So, it is better to start with one term and then add others one at a time. While you may not be able to get quality results with all of the search terms, you can mix and match the information in different combinations to arrive at an answer to your clinical question.

The best way to start your search is by using your problem (disease process) term. From our example above, we would start by searching for “prostate cancer.” If you don’t know the exact disease process, try searching “differential diagnosis” AND the symptoms the patient is experiencing.

Quotation Marks

If you are searching for a term that has more than one word or a phrase, you will want to enclose the search term in quotation marks. This tells the computer that these words must appear in this exact order with no words appearing between the terms. If you don’t use the quotation marks, the computer will treat your search as an AND search (more on this in Boolean Operators, below) and return all articles that include those terms in any order, anywhere in the article, which is much less likely to meet your needs. For example, if you are wanting information on the stages of grief, just typing stages of grief in the search box will return all articles with the word stages and the word of, and the word grief anywhere in it. If you enter “stages of grief” in the search box, the computer will only return articles with the exact phrase “stages of grief” in it. You can see how the second approach will give you much more relevant information.

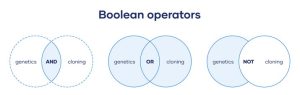

Boolean Operators

Once we are ready to start combining terms into our search, we want to use Boolean Operators. We know that everything a computer does is boiled down to a math problem. One of the ways we can structure these math problems is with Boolean operators. Boolean Operators are simple words (OR, AND, or NOT) used as conjunctions to combine or exclude keywords in a search, resulting in more focused and productive results. This should save time and effort by eliminating inappropriate hits that must be scanned before discarding. Boolean Logic is named for George Boole, a mathematician who had the happy thought that you can combine sets with OR, AND, or NOT. Each search engine or database collection uses Boolean operators in a slightly different way or may require the operator be typed in capitals or have special punctuation. The specific phrasing will be found in either the guide to the specific database found in Research Resources or the search engine’s help screens.

OR

The OR operator is used to combine terms to get more results. Using OR broadens the search. If there isn’t much on your topic, combine terms (e.g. subject terms & the keyword terms) with OR to find the most resources. Using our example above, we could search for “older adult” OR “above 65” OR geriatric. This search will return more resources than if we just searched for “older adult” by itself. This is one of the ways you can use the synonyms you came up with when determining your search terms. You can also try each synonym individually to determine if that term retrieves any useful information.

AND

The AND operator is used to combine topics and get fewer results. Using AND narrows the search. Searches with AND require both terms to be in each item returned. If one term is contained in the document and the other is not, the item is not included in the resulting list. Using our example above we can combine a search for the problem (prostate cancer) with the action we are undertaking (diagnostic testing or screening). The search entry would look like:

“prostate cancer” AND “diagnostic testing”

Both terms are encased in quotation marks because they are 2-word terms. If we wanted to include the alternate action term “screening” in addition to “diagnostic testing,” we will include the second half of our search in parenthesis like this:

“prostate cancer” AND (“diagnostic testing” OR screening)

NOT

The NOT operator (sometimes AND NOT depending on the coding of the database’s search engine) is used to exclude words from your search. Using NOT narrows the search. Using NOT provides results that contain the first keyword but not the second. When you use NOT you are telling the computer to ignore any resources that include that term, even if it included the original term. Make sure to put your keywords in the correct order when using NOT, as the search results provided will exclude the latter keyword. An example would be if we were wanting to know more about cloning, but didn’t want documents that deal with cloning sheep. That search entry would look like:

cloning NOT sheep

In the image above, the blue shading represents the resources that will be returned with each type of search.

Collecting the Relevant Resources

Citation Engines

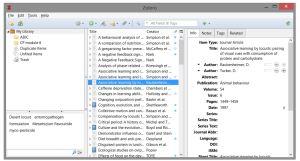

Zotero

There are many citation managers to chose from, but Zotero is recommended for the following reasons:

- Zotero is free (you can pay for more storage space)

- Zotero is open-source and run by a non-profit

- Many popular citation managers are run by publishers that use your data for profit

- Zotero has a great support

- Zotero is easy to use

A Video to Get You Started

Downloading Zotero

Download the two components of Zotero at https://www.zotero.org/download/

- Zotero Desktop: where you can see and organize your citations

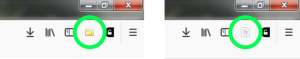

- Zotero Connector: a browser plugin that automatically detects content as you browse the web and allows you to save it to Zotero with a single click

The Zotero icon changes depending on what type of material you are looking at. A folder for a list of items and a paper for a journal article.

Adding Items to Zotero

There are two main ways to add item to Zotero:

- Zotero Connector

- Use the Zotero button to automatically add materials to Zotoro

- Click on the Zotero icon in your browser toolbar and the document will automatically be downloaded into the Library folder you have open on Zotero Desktop.

- If you are on a webpage that includes the pdf of an article, Zotero will automatically download the article

- Watch your Desktop Library to make sure the author and year are included in the metadata

- Use the Zotero button to automatically add materials to Zotoro

- Adding pdfs

- You can manually drag-and-drop pdfs into the main window of Zotero desktop to add those item to Zotero

Organizing with Zotero

In the Zotero desktop you can:

- Create folders to organize your resources

- Add tags and notes to items

- Search by keyword to find your resources

Citing with Zotero

Creating Citations with Zotero

To cite in Word or Open Office:

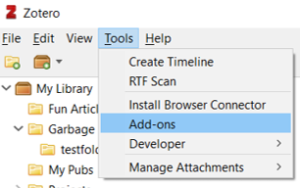

- Enable the Zotero plug in

- Go to Tools > Add-ons and choose your plug in (you may need to restart your computer)

- Use the Zotero tool bar to add citations and create a bibliography

Zotero Help

Zotero Quick Start Guide – Guide to help you get started with Zotero

Zotero Support – For more in depth help

Key Takeaways

Always double check that your citations are correct, even when you use a citation manager

- If your citation manager has the wrong information, your citation will be wrong

- Always update or edit citation information in Zotero to correct your citation

- If you edit a citation in Word or Google Docs, the edit will be undone when you refresh.

Hints for Using Zotero with Word on a Mac

After installing Zotero standalone to your computer, Word should show either a new Zotero tab next to the Home, Review, View tabs,

OR it will show a separate tool bar with 5 little red icons just below that tab bar (for Word 2011).

If it does not show up – Double check Word to see if the Zotero plugin is correctly installed:

If that STILL doesn’t work:

-

Open Word Preferences.

-

Click View.

-

Check “Show developer tab” and close the preferences dialog.

-

In the new Developer tab click “Word Add-ins”.

-

Make sure that “Zotero.dotm” is present under Global Templates and Add-ins” and is checked.If the “Zotero.dotm” entry isn’t present in the dialog, try reinstalling the Word plugin from Zotero. In Zotero, go to the Cite pane of the Zotero preferences, click the “Reinstall Word Components” button, and then restart Word.

References

Coombs, Philip Espinola. “Research Subject Guides: Systematic Reviews and Evidence Syntheses: Databases.” Northeastern University, January 12, 2023. https://subjectguides.lib.neu.edu/systematicreview/databases.

Howlett, Bernadette, and Ellen J Rogo. “What Evidence-Based Practice Is and Why It Matters.” In Evidence-Based Practice for Health Professionals, 5–30. Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC., 2014.

John Wiley & Sons, Inc. “About the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews.” Cochrane Library, 2023. https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/about-cdsr.

Kendall, Sandra. “Evidence-Based Resources Simplified.” Canadian Family Physician 54, no. 2 (February 2008): 241–43. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2278320/.

Murad, M. Hassan, Noor Asi, Mouaz Alsawas, and Fares Alahdab. “New Evidence Pyramid.” BMJ Evidence-Based Medicine 21, no. 4 (August 1, 2016): 125–27. https://doi.org/10.1136/ebmed-2016-110401.

Siu, Albert L. and U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. “Screening for Breast Cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement.” Annals of Internal Medicine 164, no. 4 (February 16, 2016): 279–96. https://doi.org/10.7326/M15-2886.

Stieglitz, L. (2020). Citation Management with Zotero. https://openeducationalberta.ca/advancedlibsearch/chapter/zotero/

Turner, Murray. “Evidence-Based Practice in Health: Hierarchy of Evidence.” University of Canberra, 2014. https://canberra.libguides.com/c.php?g=599346&p=4149721.

Media Attributions

- Evidence Pyramid

- PubMed Search Results

- Start with a Plan

- Boolean Operators

- zotero_desktop

- zotero_web

- zotero_citation plug in

- zotero_ribon Word

- Zotero Toolbar in Word for Mac

- zotero-word-toolbar

- Enabling Zotero Toolbar