Colonial Literature – Of the Revolution – Franklin, Crevecoeur, Paine

29 Author Introduction– Benjamin Franklin (1706–1790)

Wendy Kurant

Born in Boston, Benjamin Franklin was the youngest son of the youngest son five generations back. His father, Josiah Franklin, left Northamptonshire, England for America in reaction against the Church of England. Though he tried to have his son educated formally by enrolling him in the Boston Grammar School, Josiah was forced by financial circumstances to bring Benjamin into his tallow chandler and soap boiling business. Franklin hated the business, particularly the smell, so he was even- tually apprenticed to his brother James, who had learned the printing trade in England and started a newspaper, The New England Courant.

Figure 1. Benjamin Franklin at work on a printing press.

Franklin took to printing and the printed word, reading voraciously not only the business’s publications but also the books loaned to him by its patrons and friends. Through reading and using texts as models, Franklin acquired great facility in writing. An editorial he wrote under the pseudonym of “Silence Dogood” was published by his brother, who had no idea of the piece’s true authorship. James was imprisoned after quarreling with Massachusetts authorities, leaving Franklin to run the business during his absence. Franklin was only sixteen.

James also quarreled with Benjamin, who sought freedom from James’s temper and tyranny by running away, determined to make his own way in the world. In 1723, he arrived in Philadelphia and walked up the Market Street wharf munching on one of three large puffy rolls and carrying small change in his pocket. He found work as a printer there until, upon what proved to be the groundless encouragement of William Keith (1669–1749), a governor of the province, Franklin traveled to England to purchase printing equipment and start a new printing business of his own. He worked for others at printing houses for two years before returning home. While in England, he also read widely, and saw first-hand the growing importance of the periodical, the long periodical essay, and the persona of an author who served as intermediary between a large audience of readers and the news and events of the day.

He put this knowledge to good purpose once he returned to Philadelphia, first co-owning then owning outright a new printing business that published The Pennsylvania Gazette; books from the Continent; and, from 1733 to 1758, an almanac using the persona of Poor Richard, or Richard Saunders. Poor Richard’s Almanac became immensely popular, eventually selling 10,000 copies per year. With wit, puns, and word play, Franklin offered distinctly American aphorisms, maxims, and proverbs on reason versus faith, household management, thrift, the work ethic, and good manners.

In 1730, he married Deborah Read who bore two children and helped raise Franklin’s illegitimate son William. It was for William that Franklin wrote the first part of The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin. The quintessential self- made man, his business success allowed Franklin to retire at the age of forty-two and focus his energies on the common good and public affairs. He had already contributed a great deal to both, including inventing an eponymous stove and founding the first circulating library; the American Philosophical Society; and the Pennsylvania Hospital. He also promoted the establishment of the University of Pennsylvania, an institution of higher learning grounded in secular education.

He applied the tenets of this education in first-hand observation and study of the natural world, from earthquakes to electricity. His Experiments and Observations on Electricity (1751–1753) won him the respect of scientists around the world. Like other humanist-deist thinkers of his day, Franklin used reason to overcome institutional tyrannies over mind and body. Between the years 1757 and 1775, he actively sought to overcome England’s tyranny over the colonies in two separate diplomatic missions to England, representing Pennsylvania, Georgia, Massachusetts, and New Jersey and also protesting the Stamp Act.

The rising sense of injustice against England led to the First and then the Second Continental Congresses, at the latter of which Franklin represented Pennsylvania and served with Thomas Jefferson on the committee that drafted the 1776 Declaration of Independence, a declaration that represented all thirteen colonies. Central to the beginning of the American Revolution, Franklin was also central to its end in 1783 through the Treaty of Paris that he, John Jay, and John Adams shaped and signed. And he helped shape the future of the United States of America by serving on the Constitutional Convention that wrote the Constitution and the Bill of Rights.

Throughout all these great actions and events, Franklin wrote didactic works leavened by an extraordinary blend of worldliness and earnestness and enlivened by wit, humor, and sometimes deceptive irony.

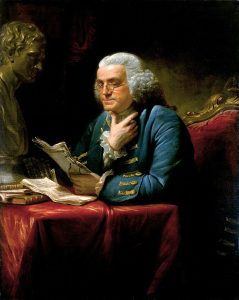

Figure 2. Benjamin Franklin 1767

Source:

Becoming America, Wendy Kurant, ed., CC-BY-SA

Image Credit:

Figure 1. “Benjamin Franklin at work on a printing press,” Charles Mills, Wikimedia, Public Domain.

Figure 2. “Benjamin Franklin 1767,” David Martin, Wikimedia, Public Domain.